使用简单搅拌容器在藻酸盐珠中的哺乳动物细胞包封

Summary

该视频和手稿描述了一种基于乳液的方法,以将哺乳动物细胞包封在0.5%至10%的藻酸盐珠中,其可以使用简单的搅拌容器以大批量生产。包封的细胞可以在体外培养或移植用于细胞治疗应用。

Abstract

藻酸盐珠粒中的细胞包封已被用于体外固定化细胞培养以及体内免疫隔离。已经广泛研究胰岛包囊作为增加同种异体或异种移植物中胰岛存活的手段。藻酸盐封装通常通过喷嘴挤出和外部凝胶化来实现。使用这种方法,在喷嘴尖端形成的含细胞的藻酸盐液滴落入含有二价阳离子的溶液中,这些二价阳离子在它们扩散到液滴中时会引起离子型藻酸盐凝胶化。在喷嘴尖端形成液滴的要求限制了可以实现的体积通量和藻酸盐浓度。该视频描述了可扩展的乳化方法,以0.5%至10%的藻酸盐包封哺乳动物细胞,其中70%至90%的细胞存活。通过这种替代方法,含有细胞和碳酸钙的藻酸盐液滴在矿物油中乳化由于pH降低,导致内部钙释放和离子型藻酸盐凝胶化。目前的方法允许在乳化20分钟内生产藻酸盐珠粒。封装步骤所需的设备包括可供大多数实验室使用的简单搅拌容器。

Introduction

已经广泛研究了哺乳动物细胞包封作为保护移植细胞免于免疫排斥的手段1或为固定的细胞培养2,3,4提供三维支持。藻酸盐珠粒中的胰岛包囊已经用于逆转异种5,6或异种7,8,9,10,11 和 12啮齿动物中的糖尿病。包封胰岛移植治疗1型糖尿病的临床前和临床试验正在进行中13,14,15 。适用于移植应用或大规模应用通常使用体外固定化的细胞生产,基于喷嘴的珠发生器。通常,藻酸盐和细胞的混合物通过喷嘴泵送以形成落入含有二价阳离子的搅拌溶液中的液滴,导致液滴的外部凝胶化。同轴气流16,17 ,喷嘴振动18 ,静电排斥19或旋转导线20有助于在喷嘴尖端形成液滴。

常规珠发生器的主要缺点是其有限的生产量和溶液粘度的有限范围,这将导致足够的珠形成21 。在高流速下,离开喷嘴的流体分解成小于喷嘴直径的液滴,减小了尺寸控制。多喷嘴珠发生器可用于提高生产量,但是喷嘴之间流动的均匀分布和> 0.2Pa的溶液的使用是有问题的。最后,由于所使用的喷嘴的直径在100μm和500μm之间,而15%的人胰岛可以大于200μm23,因此预计所有的喷嘴基装置都会对胰岛造成一定的损害。

在这个视频中,我们描述了通过在单个乳化步骤中形成液滴而不是逐滴地包封哺乳动物细胞的另一种方法。由于珠粒生产在简单的搅拌釜中进行,所以该方法适用于小型(〜1 mL)至大规模(10 3 L范围)的珠粒生产,设备成本低24 。该方法允许使用具有短( 例如 20分钟)珠生成时间的宽范围的藻酸盐粘度来生产具有高球形度的珠粒。这种方法最初由Poncelet 等人开发湖25,26 ,用于固定DNA27,包括胰岛素29的蛋白质28和细菌30 。我们最近已经将这些方法适用于使用胰腺β细胞系31,32和原发性胰腺组织32来哺乳动物细胞的包封。

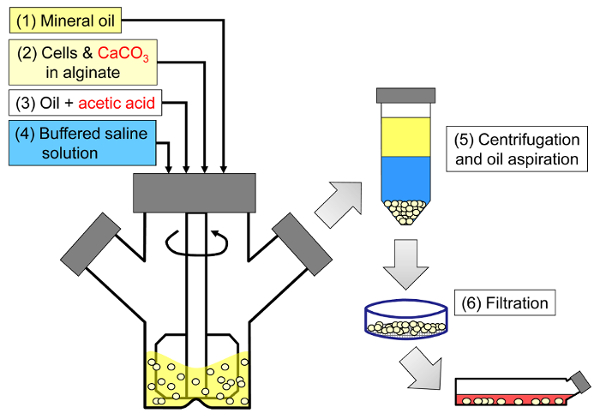

该方法的原理是在矿物油中产生由藻酸盐液滴组成的油包水乳液,随后是藻酸盐液滴的内部凝胶化( 图1 )。首先,将密封剂( 例如,细胞)分散在含有细晶粒钙盐的藻酸盐溶液中,在初始工艺pH下具有低溶解度。然后将藻酸盐混合物加入到搅拌的有机相中以产生乳液,通常在a表面活性剂。在哺乳动物细胞包封的情况下,存在于血清中的成分可以作为表面活性剂。接下来,通过加入分解成水相的油溶性酸来降低pH以便溶解钙盐。矿物油/水分配系数<0.005 33的乙酸应预先溶解在油中,然后加入到油相中混合的乳液中,并快速分配到水相34中 。 图2说明在酸化和内部凝胶化步骤期间发生的化学反应和扩散。最后,通过相转化回收包封的细胞,通过离心加速分离,重复洗涤步骤和过滤。然后可以采用珠和细胞取样进行这些步骤,用于质量控制分析, 体外细胞培养和/或包封细胞的移植。

<p class ="“jove_content”fo:keep-together.within-page" >

图1:封装哺乳动物细胞的基于乳化的方法的示意图。首先通过在矿物油中乳化藻酸盐,细胞和CaCO 3混合物(示意图中的步骤1和2)来生产珠粒,通过加入乙酸引发内部凝胶化(步骤3)。然后通过加入水性缓冲液将凝胶状珠粒与油分离以引发相转化(步骤4),然后离心和抽吸油(步骤5),然后过滤(步骤6)。最后,将过滤器上收集的珠子转移到细胞培养基中进行体外培养或移植。 请点击此处查看此图的较大版本。

<imgalt =“图2”class =“xfigimg”src =“/ files / ftp_upload / 55280 / 55280fig2.jpg”/>

图2:在内部凝胶化过程中发生的反应和扩散步骤。 (1)将乙酸加入到有机相中,并通过对流输送至藻酸盐液滴。 (2)乙酸分成水相。 (3)在水的存在下,酸解离并扩散到深蓝色所示的CaCO 3颗粒。 (4)H +离子与CaCO 3中的Ca 2+离子交换,释放Ca 2+离子。 (5)钙离子扩散直到遇到未反应的藻酸盐,导致藻酸盐链的离子交联。 请点击此处查看此图的较大版本。

与传统的基于喷嘴的细胞封装剂相反,具有宽的珠粒度分布由于在搅拌乳化中液滴形成的机理,该方法由该过程引起。对于应用的一个子集,这种珠粒度分布可能是有问题的。例如,更大部分的细胞可能在较小珠粒的珠粒表面暴露。如果关注营养( 如氧气)的限制,这些限制可能会在较大的珠粒中加剧。搅拌乳化法的优点是通过改变乳化步骤中的搅拌速度可以容易地调节平均珠粒度。也可以利用宽的珠粒度分布来研究珠粒尺寸对封装的细胞性能的影响。

通过乳化和内部凝胶化的哺乳动物细胞包封是没有配备珠粒发生器的实验室的有意义的替代方案。此外,该方法还给用户减少处理时间,或生成非常低或非常高的藻酸盐浓度的珠粒ations。

下面概述的方案描述了如何将细胞包封在10.5mL在10mM 4-(2-羟乙基)-1-哌嗪乙磺酸(HEPES)缓冲液中制备的5%藻酸盐溶液中。藻酸盐由移植级LVM(低粘度高甘露糖醛酸含量)和MVG(中等粘度高古洛糖醛酸含量)藻酸盐的50:50混合物组成。使用终浓度为24mM的碳酸钙作为物理交联剂。轻质矿物油构成有机相,而乙酸用于酸化乳液并引发内部凝胶化。然而,藻酸盐类型和组成以及所选择的过程缓冲剂取决于期望的应用32 。已经使用各种藻酸盐类型(参见表格材料)来制备具有该方案的珠粒。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

在内部凝胶化反应期间的各种步骤( 图2中所示 )可以限制整个动力学。对于大于〜2.5μm的碳酸钙颗粒,碳酸盐溶解速率已被证明是速率限制26,44 。导致内部钙释放的酸化步骤也被证明是影响细胞存活的关键过程变量32 。因此,导致内部凝胶化的条件对于珠粒质量以及细胞存活是至关重要的。根据珠粒的最终应用,可以选择不同的最佳…

Divulgations

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

我们感谢吉尔·奥斯本在乳化过程中的铺路工作以及劳伦·威尔金森的技术支持。我们感谢IgorLaçik博士,Timothy J. Kieffer博士和James D. Johnson博士的投入和合作。我们感谢魁北克省魁北克省,JDRF,ThéCell,中心区域自然科学和工程研究理事会(NSERC),人类胰岛移植和β细胞再生中心,加拿大干细胞网络,迈克尔·史密斯健康研究基金会,法国自然保护协会和COST 865财务支持。

Materials

| Reagents and consumables | |||

| LVM alginate (transplantation-grade) | Novamatrix | Non-applicable | Referred to as "alginate #1" in the results. |

| MVG alginate (transplantation-grade) | Novamatrix | Non-applicable | Referred to as "alginate #2" in the results. |

| Alginate (cell culture-grade) | Sigma | A0682 (low viscosity) or A2033 (medium viscosity) | A2033 is referred to as "alginate #3" in the results. |

| DMEM | Life Technologies | 11995-065 | |

| Fetal bovine serum, characterized, Canadian origin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | SH3039603 | |

| Glutamine | Life Technologies | 25030 | |

| Penicillin and streptomycin | Sigma | P4333-100ML | |

| HEPES, cell culture tested | Sigma | H4034-100G | |

| NaCl | Thermo Fisher Scientific | S271-1 | |

| Fine-grain CaCO3 | Avantor Materials | 1301-01 | After preparing the CaCO3 suspension, sonicate and use within one month. |

| Light mineral oil | Thermo Fisher Scientific | O121-4 | Sterile filter through a 0.22 μm pore size membrane prior to use. |

| Glacial acetic acid | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A38-500 | Handle with caution: refer to MSDS. |

| Sterile spatulas | Sigma | CLS3004-100EA | |

| Sterile nylon cell strainers, 40 µm | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 08-771-1 | |

| Serological pipettes (2 mL, 5 mL, 10 mL, 25 mL) | Sarstedt | 86.1252.001, 86.1253.001, 86.1254.001 and 86.1685.001 | |

| Pasteur pipettes | VWR | 14673-043 | |

| Toluidine Blue-O | Sigma | T3260 | |

| Equipment | |||

| 100 mL microcarrier spinner flasks | Bellco | 1965-00100 | The impeller configuration with recent models may not be suitable for adequate emulsification. A blade able to sweep the oil down to 0.5 cm from the bottom of the flask can be custom-made from a Teflon sheet. |

| Magnetic stir plate with adjustable speed | Bellco | 7760-06005 | The rotation speed should be calibrated (e.g. using a tachometer) prior to use. |

| Cell counter | Innovatis | Cedex AS20 | This system is now sold by Roche. This automated cell counter can also be replaced by manual cell enumeration after Trypan blue staining using a hemocytometer. |

| LED light box | Artograph | LightPad® PRO | This item can be replaced by other types of illuminators. |

| Handheld camera | Canon | PowerShot A590 IS | A variety of handheld cameras can be used to capture toluidine blue-o stained bead images. A ruler should be placed next to the Petri dish containing the beads prior to acquiring images. |

| Fluorescence microscope with phase contrast and adequate fluorescence filters | Olympus | IX81 | Several microscopy systems were used to image the beads. The results shown here were obtained with an IX81 microscope equipped with GFP and TRITC fluorescence filters. To capture entire beads, 4X to 20X objectives were used depending on the agitation rate. Live/dead staining images were typically captured with 20X to 40X objectives. |

| Image aquisition software | Molecular Devices | Metamorph | A variety of image acquisition software can be used to acquire phase contrast and fluorescence images. |

| Image analysis freeware | CellProfiler | Non-applicable | A variety of image analysis software can be used to identify beads as objects and analyze bead size (e.g. ImageJ). |

References

- Scharp, D. W., Marchetti, P. Encapsulated islets for diabetes therapy: history, current progress, and critical issues requiring solution. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 67-68, 35-73 (2014).

- Chayosumrit, M., Tuch, B., Sidhu, K. Alginate microcapsule for propagation and directed differentiation of hESCs to definitive endoderm. Biomaterials. 31 (3), 505-514 (2010).

- Sidhu, K., Kim, J., Chayosumrit, M., Dean, S., Sachdev, P. Alginate microcapsule as a 3D platform for propagation and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESC) to different lineages. J Vis Exp. (61), (2012).

- Tostoes, R. M., et al. Perfusion of 3D encapsulated hepatocytes–a synergistic effect enhancing long-term functionality in bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 108 (1), 41-49 (2011).

- Duvivier-Kali, V. F., Omer, A., Parent, R. J., O’Neil, J. J., Weir, G. C. Complete protection of islets against allorejection and autoimmunity by a simple barium-alginate membrane. Diabetes. 50 (8), 1698-1705 (2001).

- Omer, A., et al. Long-term normoglycemia in rats receiving transplants with encapsulated islets. Transplantation. 79 (1), 52-58 (2005).

- Rayat, G. R., Rajotte, R. V., Ao, Z., Korbutt, G. S. Microencapsulation of neonatal porcine islets: protection from human antibody/complement-mediated cytolysis in vitro and long-term reversal of diabetes in nude mice. Transplantation. 69 (6), 1084-1090 (2000).

- Korbutt, G. S., Mallett, A. G., Ao, Z., Flashner, M., Rajotte, R. V. Improved survival of microencapsulated islets during in vitro culture and enhanced metabolic function following transplantation. Diabetologia. 47 (10), 1810-1818 (2004).

- Luca, G., et al. Improved function of rat islets upon co-microencapsulation with Sertoli’s cells in alginate/poly-L-ornithine. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2 (3), E15 (2001).

- Omer, A., et al. Survival and maturation of microencapsulated porcine neonatal pancreatic cell clusters transplanted into immunocompetent diabetic mice. Diabetes. 52 (1), 69-75 (2003).

- Schneider, S., et al. Long-term graft function of adult rat and human islets encapsulated in novel alginate-based microcapsules after transplantation in immunocompetent diabetic mice. Diabetes. 54 (3), 687-693 (2005).

- Cui, H., et al. Long-term metabolic control of autoimmune diabetes in spontaneously diabetic nonobese diabetic mice by nonvascularized microencapsulated adult porcine islets. Transplantation. 88 (2), 160-169 (2009).

- Krishnan, R., Alexander, M., Robles, L., Foster, C. E., Lakey, J. R. Islet and stem cell encapsulation for clinical transplantation. Rev Diabet Stud. 11 (1), 84-101 (2014).

- Robles, L., Storrs, R., Lamb, M., Alexander, M., Lakey, J. R. Current status of islet encapsulation. Cell Transplant. 23 (11), 1321-1348 (2014).

- Desai, T., Shea, L. D. Advances in islet encapsulation technologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. , (2016).

- Anilkumar, A. V., Lacik, I., Wang, T. G. A novel reactor for making uniform capsules. Biotechnol Bioeng. 75 (5), 581-589 (2001).

- Wolters, G. H., Fritschy, W. M., Gerrits, D., van Schilfgaarde, R. A versatile alginate droplet generator applicable for microencapsulation of pancreatic islets. J Appl Biomater. 3 (4), 281-286 (1991).

- Heinzen, C., Marison, I., Berger, A., von Stockar, U. Use of vibration technology for jet break-up for encapsulation of cells, microbes and liquids in monodisperse microcapsules. Practical Aspects of Encapsulation Technologies. , 19-25 (2002).

- Poncelet, D., et al. A Parallel plate electrostatic droplet generator: Parameters affecting microbead size. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 42 (2-3), 251-255 (1994).

- Prüße, U., Dalluhn, J., Breford, J., Vorlop, K. D. Production of Spherical Beads by JetCutting. Chemical Engineering & Technology. 23 (12), 1105-1110 (2000).

- Hoesli, C. A. . Bioprocess development for the cell-based treatment of diabetes (PhD thesis). , (2010).

- Brandenberger, H., Widmer, F. A new multinozzle encapsulation/immobilisation system to produce uniform beads of alginate. J Biotechnol. 63 (1), 73-80 (1998).

- Merani, S., Toso, C., Emamaullee, J., Shapiro, A. M. Optimal implantation site for pancreatic islet transplantation. Br J Surg. 95 (12), 1449-1461 (2008).

- Reis, C. P., Neufeld, R. J., Vilela, S., Ribeiro, A. J., Veiga, F. Review and current status of emulsion/dispersion technology using an internal gelation process for the design of alginate particles. J Microencapsul. 23 (3), 245-257 (2006).

- Poncelet, D., et al. Production of alginate beads by emulsification/internal gelation. I. Methodology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 38 (1), 39-45 (1992).

- Poncelet, D., et al. Production of alginate beads by emulsification/internal gelation. II. Physicochemistry. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 43 (4), 644-650 (1995).

- Alexakis, T., et al. Microencapsulation of DNA within alginate microspheres and crosslinked chitosan membranes for in vivo application. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 50 (1), 93-106 (1995).

- Vandenberg, G. W., De La Noue, J. Evaluation of protein release from chitosan-alginate microcapsules produced using external or internal gelation. J Microencapsul. 18 (4), 433-441 (2001).

- Silva, C. M., Ribeiro, A. J., Figueiredo, I. V., Goncalves, A. R., Veiga, F. Alginate microspheres prepared by internal gelation: development and effect on insulin stability. Int J Pharm. 311 (1-2), 1-10 (2006).

- Larisch, B. C., Poncelet, D., Champagne, C. P., Neufeld, R. J. Microencapsulation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. J Microencapsul. 11 (2), 189-195 (1994).

- Hoesli, C. A., et al. Reversal of diabetes by betaTC3 cells encapsulated in alginate beads generated by emulsion and internal gelation. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 100 (4), 1017-1028 (2012).

- Hoesli, C. A., et al. Pancreatic cell immobilization in alginate beads produced by emulsion and internal gelation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 108 (2), 424-434 (2011).

- Reinsel, M. A., Borkowski, J. J., Sears, J. T. Partition Coefficients for Acetic, Propionic, and Butyric Acids in a Crude Oil/Water System. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 39 (3), 513-516 (1994).

- Xiu-Dong, L., Wei-Ting, Y., Jun-Zhang, L., Xiao-Jun, M., Quan, Y. Diffusion of acetic acid across oil/water interface in emulsification-internal gelation process for preparation of alginate gel beads. Chemical Research in Chinese Universities. 23 (5), 579-584 (2007).

- Fernandez, S. A., et al. Emulsion-based islet encapsulation: predicting and overcoming islet hypoxia. Bioencapsulation Innovations. (220), 14-15 (2014).

- Carpenter, A. E., et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7 (10), R100 (2006).

- Hinze, J. O. Fundamentals of the hydrodynamic mechanism of splitting in dispersion processes. AIChE Journal. 1 (3), 289-295 (1955).

- Kolmogorov, A. N. On the breakage of drops in a turbulent flow (translated from Russian). Doklady Akademii Nauk. 66, 825-828 (1949).

- Davies, J. T. Drop Sizes of Emulsions Related to Turbulent Energy-Dissipation Rates. Chemical Engineering Science. 40 (5), 839-842 (1985).

- Pacek, A. W., Chamsart, S., Nienow, A. W., Bakker, A. The influence of impeller type on mean drop size and drop size distribution in an agitated vessel. Chemical Engineering Science. 54 (19), 4211-4222 (1999).

- Steiner, H., et al. Numerical simulation and experimental study of emulsification in a narrow-gap homogenizer. Chemical Engineering Science. 61 (17), 5841-5855 (2006).

- Tcholakova, S., Denkov, N. D., Lips, A. Comparison of solid particles, globular proteins and surfactants as emulsifiers. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 10 (12), 1608-1627 (2008).

- Lagisetty, J. S., Das, P. K., Kumar, R., Gandhi, K. S. Breakage of viscous and non-Newtonian drops in stirred dispersions. Chemical Engineering Science. 41 (1), 65-72 (1986).

- Draget, K. I., Ostgaard, K., Smidsrod, O. Homogeneous Alginate Gels – a Technical Approach. Carbohydrate Polymers. 14 (2), 159-178 (1990).

- Poncelet, D., Dulieu, C., Jacquot, M., Wijffels, R. H. . Immobilized Cells. , 15-30 (2001).

- Islam, A. W., Zavvadi, A., Kabadi, V. N. Analysis of Partition Coefficients of Ternary Liquid-Liquid Equilibrium Systems and Finding Consistency Using Uniquac Model. Chemical and Process Engineering-Inzynieria Chemiczna I Procesowa. 33 (2), 243-253 (2012).

- Quong, D., Neufeld, R. J., Skjak-Braek, G., Poncelet, D. External versus internal source of calcium during the gelation of alginate beads for DNA encapsulation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 57 (4), 438-446 (1998).

- De Vos, P., De Haan, B. J., Van Schilfgaarde, R. Upscaling the production of microencapsulated pancreatic islets. Biomaterials. 18 (16), 1085-1090 (1997).

- Gross, J. D., Constantinidis, I., Sambanis, A. Modeling of encapsulated cell systems. J Theor Biol. 244 (3), 500-510 (2007).