자폐 스펙트럼 장애의 실행 기능

English

Diviser

Vue d'ensemble

출처: 조나스 T. 카플란과 사라 I. 짐벨의 연구소 – 서던 캘리포니아 대학

주의, 작업 메모리, 계획, 충동 제어, 억제 및 정신적 유연성은 종종 집행 기능이라고하는 인간의 인식의 중요한 구성 요소입니다. 자폐 스펙트럼 장애는 사회적 상호 작용, 의사 소통 및 반복적 인 행동의 장애를 특징으로하는 발달 장애입니다. 그것은 일생을 지속하는 무질서이고, 인구의 0.6%에 영향을 미치기 위하여 생각됩니다. 자폐증의 현상은 전문화한 신경 심리학 시험에 의해 평가될 수 있는 집행 기능에 있는 적자를 건의합니다. 각각 집행 기능의 다른 측면을 강조 하는 몇 가지 테스트를 채택 하 여, 우리는 장애의 인지 프로필의 더 완벽 한 그림을 얻을 수 있습니다.

위스콘신 카드 선별 테스트 (WCST)로 알려진 이러한 작업 중 하나는 집행 기능의 적자에 대한 매우 민감한 척도로서 연구 및 임상 연구에서 널리 사용되는 인지적으로 복잡한 작업입니다. 주의를 돌리는 사람의 능력을 테스트하고 규칙 과 보강을 변경하여 유연성을 테스트합니다. 1 WCST에서 참가자는 색상, 모양 및 숫자의 세 가지 자극 매개 변수를 통합한 네 개의 자극 카드를 제공합니다. 참가자는 다른 원칙에 따라 응답 카드를 정렬하여 실험자의 피드백에 따라 정렬 기준을 변경하도록 요청받습니다. 참가자는 카드를 정렬하는 올바른 방법을 찾을 때까지 다른 규칙을 시도합니다. 임원 기능 장애를 가진 환자는 카드 정렬 작업에 갇혀 얻을 하는 경향이, 그들의 정렬 전략을 변경할 수 없습니다. 잘못된 전략을 가진 이러한 지속성은 인내라고합니다.

두 번째 작업인 The Tower of London (ToL)은 복잡한 계획, 재평가 및 계획된 이동 업데이트에 의존하는 테스트입니다. 자폐증을 가진 개별은 계획과 관련되었던 업무에 손상되기 위하여 보고되었습니다. 2 ToL 작업에서 개인은 특정 규칙에 따라 가능한 한 적은 이동에서 목표 상태를 일치시키기 위해 세 개의 못에 미리 정렬된 시퀀스에서 디스크를 이동해야 합니다.

Stroop 테스트로 알려진 세 번째 작업은 인지 억제를 목표로 합니다. 이 작업 참가자는 다른 색상으로 작성된 색상의 이름을 표시하고 단어가 기록된 색상을 식별하라는 메시지가 표시됩니다. 예를 들어 위화감이 없는 상태에서 파란색이라는 단어는 녹색으로 작성됩니다. 억제 어려움을 가진 개인뿐만 아니라 일반적으로 서면 단어의 억제를 포함하는이 작업에 개인을 개발하지 않아야.

이 비디오에서는 WCST, ToL 및 Stroop 작업을 관리하여 자폐 스펙트럼 장애가있는 어린이의 유연성, 계획 및 억제를 비교하고 일반적으로 대응 을 개발하고 각 그룹이 집행 기능의 이러한 다양한 측면을 수행하는 방법을 탐구하는 방법을 보여줍니다.

Procédure

Résultats

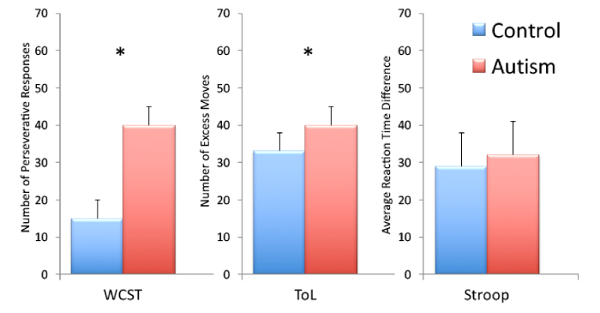

Individuals with autism perform significantly worse on tests of mental flexibility and planning, but do not show a difference from typically developing individuals in tests of inhibition (Figure 4). 6 In the WCST, a test measuring mental flexibility, individuals with autism are less able to set-shift, adjusting to a new sorting rule mid-task (i.e., they make more perseverative errors). Consistent deficits have been found in the total number of categories correctly identified and the total number of errors made (Figure 4, left). The ToL test can be used to examine specific aspects of difficulty in planning. Even though the autistic group was impaired in relation to the control group (Figure 4, middle), this deficit was evident only on puzzles that required longer sequences of moves. On the classic Stroop test of inhibition, autistic participants were not impaired in comparison to typically developing participants (Figure 4, right). In summary, autistic and normally developing children show a difference in performance on tasks of planning and mental flexibility, but not on this task of inhibition.

Figure 4. Performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Tower of London test (ToL) and Stroop task. Participants in the autism group (blue) were more impaired on the WCST and ToL tests, but there was no difference between the autism group and control group (red) in the Stroop task.

Applications and Summary

This cognitive battery of tasks to examine executive function could possibly be used as a diagnostic marker for autism. While there are many disorders of executive function, it is possible that the pattern of performance on different tests examining different components of executive function may lead to a dissociation between different disorders. Executive function disorders such as autism, ADHD, Tourette’s syndrome, and conduct disorder may have differing executive profiles in regard to these, and related, tasks. If a specific, yet differential, profile of executive dysfunction can be identified in these disorders, then it could be possible to use measures of executive function as a marker for the diagnosis of autism. Furthermore, understanding the specific profile of cognitive disabilities in this disorder can help develop more targeted rehabilitation and training programs.

References

- Grant, D. A. and Berg, E. A. (1948). A behavioural analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card sorting problem. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 404-411.

- Ozonoff, S. et al. (1991) Executive function deficits in high-functioning autistic individuals: relationship to theory of mind. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 32, 1081-1105

- Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Dis- orders, 24, 659-685.

- Lord, C., Rutter, M. L., Goode, S., Heemsbergen, J., Jordan, H., Mawhood, L., & Schopler, E. (1989). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: A standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19, 185-212.

- Heaton, R. K. (1981). Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

- Hill, E. L. (2004). Executive Dysfunction in Autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(1), 26-32.

Transcription

Autism Spectrum Disorder is characterized by impairments in communication and executive function, with an onset that is often noted during early childhood.

Across normal development, children improve their executive processes, which include: flexibility—adapting thoughts in response to a changing environment; planning—the actions needed to attain a specific goal, and inhibition—being able to stop what they’re doing

However, in this social situation, the child who showed difficulty executing those functions—the one who didn’t go inside to get a coat because he kept waving a stick around—is an example of someone with components indicative of Autism Spectrum Disorder.

This video demonstrates how to perform a series of behavioral tests that tap into the processes of executive function in the laboratory, as well as how to analyze the data and interpret results in children diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder compared to those without any known developmental disorders.

In this experiment, children with Autism Spectrum Disorder along with typically developing counterparts ages 6 to 18 are asked to complete three tasks—the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, the Tower of London, and the Stroop Task—that measure different components of executive function.

In the first task, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, children are presented with four stimulus cards that incorporate three stimulus patterns: color, shape, and number.

They are asked to sort response cards according to one of these parameters, but the trick here is that they must figure out the sorting rule based on the feedback provided after matching each one.

Participants try sorting by color, shape, or number until they find the acceptable rule, which is applied for a run of 10 correct placements and then changed without warning.

The dependent variable then is the number of responses in which the participant continues to sort based on the previously correct rule, despite feedback that it was incorrect. This is known as perseveration: focusing on the same response even though it may not lead to an advantageous outcome.

The second task is the Tower of London, where participants must move disks from a prearranged sequence on three pegs to match a goal state in as few steps as possible. In this case, the dependent variable is number of moves made that surpass the minimum number necessary.

The third and final task is the Stroop test, where participants are asked to say out loud the colors of presented words. The colored terms are equally divided into either congruent trials—where the name and font color match, or incongruent ones—the two features are mismatched, for example, the word green is colored blue.

Here, the dependent variable is the time it takes for participants to say the correct color. Responses in the incongruent condition tend to be slower than congruent trials because participants must inhibit reading the word, which is fast and automatic, in favor of saying the actual color of the letters.

The symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder suggest deficiencies in the executive functions required to complete the three tasks. It is predicted that participants already diagnosed with the disorder will not have the same flexibility as controls with changing rules in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

Likewise, they are also expected to demonstrate poor planning when solving the Tower of London, and reduced cognitive inhibition to correctly complete the Stroop test, compared to aged-matched and typically developing participants.

To begin, greet the recruited participant and have them sit comfortably in front of a computer. Note that all participants should be age- and intellect-matched. After gaining parental approval, guide them through the consent forms.

Now, explain to each participant that they will complete three tasks: first is the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, where they have to match a single card to one of the four displayed on the screen. Elaborate that the cards can match in either color, shape, or number and that they will be told if their guess was correct or not.

Further inform them that, from time to time, the rule will change without notice and that they will have to discover the switch on their own to get as many as possible correct. Answer any questions they might have.

Then, start the task, and allow the participant time to complete the trials, which depends on either six runs of 10 correct placements or until all 64 cards have been sorted. When the task ends, provide them with a 2-min break.

Once the break is over, have the participant sit down again. Explain that the second task—the Tower of London—involves rearranging the configuration of three colored balls located on three pegs, and that their objective is to match the goal configuration in the shortest number of moves.

Also inform them that they should preplan the series of moves and to remember that a transfer cannot be undone. Following the instructions, allow them to complete 20 trials, using the mouse to execute their intended movements.

After another 2-min break, start the third and final test—the Stroop Task. Explain that in this case, a word will be displayed on the screen for up to 4 s, with 1.5 s in between each, and they are to say out loud, the color that the word is written in.

Note that the computer program logs reaction times based on the onset of the spoken color, over the course of 120 trials. You’ll still need to quickly record the participant’s verbalized responses and whether they are correct or not, between word presentations.

To analyze the data, evaluate each task individually: for the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, determine the average number of perseveration responses; for the Tower of London, calculate the average number of excessive moves beyond the minimum required to solve each puzzle; and for the Stroop Task, average the difference in reaction times for naming the words in the incongruent compared to the congruent condition.

Plot the results for both control and autistic spectrum individuals across all tasks. First, in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, notice that participants with autism were less able to set-shift, or adjust to a new sorting rule mid-task.

In other words, they tended to get stuck in the card-sorting task and were unable to change their sorting strategy, which resulted in more perseverative errors.

In the Tower of London test, the autistic spectrum participants showed a deficit in the ability to solve the puzzle using the minimum number of moves, suggesting impairments in planning.

As for the Stroop test, both groups had the same reaction times, indicating that cognitive inhibition was not affected.

Now that you are familiar with several tests of executive function, let’s look at how such batteries could be used to diagnose and differentiate disorders with cognitive dysfunctions and possibly even lead to rehabilitation in these individuals.

While there are many neurodevelopmental disorders with impairments of executive function, including Autism, ADHD, and Tourette’s Syndrome, they may have differing executive profiles. For instance, as we’ve shown here, those with Autism Spectrum Disorders show deficits in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and Tower of London.

In contrast, children with ADHD demonstrate impairments in the Tower of London and Stroop Task, whereas those with Tourette’s Syndrome primarily display deficits in the Stroop Task.

Thus, if specific, yet differential, patterns of cognitive dysfunction can be identified across disorders, series of behavioral measures could be used as indicators during diagnosis.

In addition, understanding the cognitive differences amongst different disorders can lead to the development of more targeted rehabilitation programs, like using transcranial direct current stimulation.

Brain regions can be targeted, like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, before and after behavioral tasks. That way, researchers can measure whether stimulation enhances executive function, providing a promising approach for rehabilitating a number of disorders with distinct neural underpinnings.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s introduction to executive function in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design and run a Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, the Tower of London test and the Stroop test, as well as how to analyze and assess the results.

Thanks for watching!