감정 유도

English

Diviser

Vue d'ensemble

출처: 윌리엄 브래디 & 제이 반 바벨-뉴욕 대학교

심리학자들은 사람들이 좋은 기분과 나쁜 기분에 대해 다르게 행동한다는 것을 오랫동안 알고 있으며,이 일반적인 원칙은 소비자 행동으로 확장됩니다. 경제학자들은 또한 개인의 재정적 결정이 전적으로 광범위한 비용 이점 계산의 결과가 아니라는 점을 인정하게 되었습니다. 감정과 같은 다른 요인이 작용하고 있습니다. 또한, 부수적인 감정은 구매자와 판매자의 행동에 영향을 미칩니다. 이전 연구는 글로벌 감정의 영향에 초점을 맞추고 있지만 (긍정적 인 부정적인), 더 최근의 연구는 더 구체적인 감정을 검사(예를 들어,분노와 두려움). 소비자 설정에서, 연구는 분노가 구매자와 판매자 들 사이에서 더 큰 위험 추구 행동을 트리거하고 그 공포는 반대, 즉,보수적 인 행동을 트리거한다는 것을 보여줍니다.

다음 실험은 혐오와 슬픔과 같은 두 가지 부정적인 감정이 사람들의 개체에 대한 재정적 평가에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 테스트합니다. 1 실험은 유도된 감정 상태(혐오와 슬픔)와 인다우먼트 효과 사이의 관계를 조사한다. 이 실험에 내재된 것은 실험실 환경에서 특정 감정을 유도하는 일반적인 기술입니다. 감정이 만들어지면 여러 실험 조건에서 구현할 수 있습니다.

Principles

Procédure

Résultats

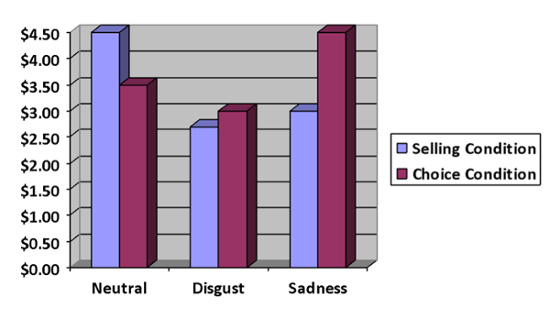

The data (Figure 1) show support for the idea that compared to the neutral condition, sadness decreased the prices for those in the selling condition, but increased prices for those in the choice condition. However, compared to the neutral condition, disgust reduced prices for participants in both the selling and choice conditions.

Figure 1: Results showing average selling and choice prices for neutral participants, disgusted participants and sad participants. Price is on the y-axis and and experimental condition is on the x-axis.

Applications and Summary

Although they are both negative emotions, disgust and sadness trigger different economic behavior. Disgust triggers the psychological need to expel, thus reducing both buying and selling prices. Conversely, sadness triggers the psychological need to change one’s circumstances, thus increasing buying prices and decreasing selling prices. With disgust, the endowment effect is eliminated, whereas with sadness the effect is reversed.

Emotion and cognition influence one another. Our appraisals of situations can drive emotions, and our emotional states can influence the way we think. Moreover, decisions are rarely made in an emotional vacuum; often, people are experiencing strong emotions before, during, and after they make decisions. Even our calculations of economic value are influenced by our emotional states. For example, the sadness from going through a divorce could actually alter our consumer-spending.

This study has clear implications for advertising and marketing. These findings suggest that people are willing to spend more for an item when they are sad, which could be leveraged by producing sadness-inducing marketing and by pricing items higher in situations in which consumers are likely to be sad. People are less willing to spend money when disgusted, likely because they value objects less (perhaps due to a sense of contamination). Thus, marketers should avoid inducing disgust in consumers. This is an important insight, given that mild comic disgust is quite common in advertising. Conversely, someone seeking to buy something might want to make the seller feel disgust, as they may be willing to sell the item for a lower price.

References

- Lerner, J. S., Small, D. A., & Lowenstein, G. (2004). Heart strings and purse strings: Carryover Effects of emotions on economic decisions. Psychological Science, 15, 337-341.

Transcription

People behave differently based on their mood, and as it turns out, this principle extends to the consumer market, where financial decisions are not just the result of cost-benefit calculations; other factors—like emotion—are at play when valuing particular items.

For instance, while an individual is shopping online for a new instrument, his friend calls and they get into a heated discussion. The resulting state of anger triggers greater risk-seeking behavior, and he purchases an unreasonably high-priced item.

His roommate—as a witness to the ordeal—now feels afraid, and in this different negative state of fear, is more uncertain about the product and contrarily thinks that it’s priced too high to buy.

In such cases, anger and fear are known as incidental emotions—feelings that consumers carry with them into potential financial transactions but are unrelated to the potential purchases at hand.

This video demonstrates how to induce incidental emotions—specifically disgust and sadness—and test their influences on individuals’ financial valuations of objects—just how much they would pay or want to be paid for something.

This experiment consists of two parts: in Phase 1, participants are assigned to either a selling or choice condition and then watch videos to induce specific emotions. In Phase 2, they are asked how much they would sell or buy a particular object for.

During Phase 1, half of the participants—those in the selling condition—are endowed with a highlighter set and instructed that they will use it in a subsequent study. The other half in the choice condition does not receive it.

To measure pre-existing feelings, each participant is first asked to complete a self-reported questionnaire—the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. Following this baseline assessment, participants are randomly assigned to watch one of three, 4-min video clips to induce emotions.

In the sadness condition, the chosen scene is from a depressing movie—one that involves a significant character dying. For the second disgust group, a situation that is repulsive, like entering an unsanitary room, is portrayed. Lastly, in the neutral condition, a nature documentary is shown.

During this observation phase, participants in the experimental groups—sadness and disgust—are asked to imagine what it would feel like if they were personally in the situation shown in the clip and to write down their feelings. Those in the control group—watching the neutral video—are instructed to simply write about their daily activities.

For Phase 2, participants who were assigned to the selling condition are presented with a list of 28 prices, ranging from $0.50 to $14, and are asked to indicate, at each price, whether they would prefer to sell the highlighter set or keep it.

Those in the choice condition are shown the markers and then given the same list of 28 prices. In this case, they are asked if they would rather have the amount of money listed or the highlighter set.

Finally, to see if the expected emotions were induced, participants are once again given a list of affective states, including blue, downhearted, and sad, as well as disgusted and repulsed. They are asked to rate whether they feel any of them on a scale of 0 (do not experience emotion at all) to 8 (experience the emotion more strongly than ever before).

In this experiment, the dependent variable is the average cost at which participants would either sell their highlighter set or choose to buy it. Averages are calculated for each emotion and buy/sell conditions.

Based on previous work, disgust evokes the need to expel and avoid acquiring anything new. Therefore, it is predicted that participants in this emotional state will reduce both selling prices—amongst those who possessed the item—and buying prices—for those who did not have ownership—relative to the neutral conditions.

Such findings would eliminate the endowment effect—the tendency for people to overvalue objects that they own.

Conversely, sadness triggers the psychological need to change one’s circumstances. Thus, it’s hypothesized that individuals feeling down will decrease selling prices to get rid of what they have, whereas the others will increase their buying price to acquire something new. In this case, the endowment effect is reversed.

Prior to the experiment, conduct a power analysis to recruit a sufficient number of participants for this 3 x 2 between-subjects design.

Then, arrange two packets of material for each individual: In the first one, insert a questionnaire called the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule and a sheet to write down their thoughts; in the second, enclose a highlighter set for those randomly assigned to the selling condition, a price list, and another survey on affective states.

To begin, escort a participant into the testing room near a computer and headphones. Inform them that they are going to complete two separate studies, and hand out the materials for both.

Now, instruct participants to open their envelopes. Notice that those randomly assigned to the selling condition were given a highlighter set to use in the 2nd study, whereas those in the choice condition were not provided with one.

As a baseline self-assessment, ask each participant to fill out the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule questionnaire. After the form is completed, play one of three, 4-min video clips.

For participants watching the clips of sadness or disgust, ask them to imagine what it would feel like if they were personally in the situation shown in the clip and to write down their feelings. For those watching the neutral clip, simply have them write about their daily activities.

To start the second phase, instruct participants to retrieve the list of 28 price amounts, ranging from $0.50 cents to $14.

For those assigned to the selling condition, ask them to indicate, for each price, whether they prefer to sell the highlighter set or keep it. On the other hand, for those in the choice condition, have them specify if they would rather obtain the listed amount of money or the highlighter set.

Afterwards, direct each participant to complete the final list of affective states, in which they should remark on whether or not they experienced the emotion listed on a scale from 0 to 8. To conclude, debrief them about the details of the study.

To visualize the data, plot the average cost at which participants would sell their highlighter set or choose to obtain it across the three emotional manipulations of neutral, disgust, and sadness.

Compared to the neutral conditions, when sadness was induced, participants in the selling condition reported decreased prices, but those in the choice group reported increased amounts.

Thus, the endowment effect was reversed, suggesting that sadness evokes change—whereby individuals undervalue the objects they own and would pay more to possess something new.

However, relative to the neutral controls, disgust-induced participants indicated reduced prices in both the selling and choice conditions. In this case, the endowment effect was eliminated, implying that disgust conjures a need to expel or acquire any new objects. Collectively, even though both emotions were negative, they triggered different economic decisions.

Now that you are familiar with how to induce emotions in an experimental setting, let’s look at the implications for marketing and advertising and how businesses can alter what we value.

If people are willing to spend more for an item when they are feeling down, sadly, a salesman could get away with pushing higher-priced goods in such situations. In contrast, people are less willing to spend money when disgusted. Thus, marketers should avoid inducing this emotion in buyers.

Moreover, businesses are notorious for pumping irresistible smells into the air. This powerful manuever is intended to rapidly trigger pleasant emotions, which lure children and adults alike to purchase items they had no intention of buying prior to detecting the irresistible scents.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on inducing emotions. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design, conduct, and analyze an experiment to study how specific incidental feelings impact object valuation, as well as how emotional states can be applied to advertising and marketing.

Thanks for watching!