シンプルな攪拌槽を用いたアルギン酸ビーズにおける哺乳類細胞のカプセル化

Summary

このビデオと原稿は、簡単な撹拌容器を用いて大きなバッチで製造することができるアルギン酸ビーズ0.5%〜10%の哺乳動物細胞をカプセル化するエマルジョンベースの方法を記載しています。カプセル化された細胞は、インビトロで培養され得るか、または細胞治療用途のために移植され得る。

Abstract

アルギン酸ビーズにおける細胞のカプセル化は、インビトロでの固定培養およびインビボでの免疫隔離のために用いられてきた。膵島のカプセル化は、同種異系移植または異種移植における膵島生存を増加させる手段として広範囲に研究されている。アルギン酸塩カプセル化は、一般に、ノズル押出および外部ゲル化によって達成される。この方法を使用して、ノズルの先端に形成された細胞含有アルギン酸液滴は、液滴中に拡散する際にイオン性アルギン酸ゲル化を引き起こす二価カチオンを含む溶液に落ちる。ノズルチップにおける液滴形成の要件は、達成可能な容積スループットおよびアルギン酸塩濃度を制限する。このビデオでは、哺乳類の細胞を70%〜90%の細胞生存率で0.5%〜10%のアルギン酸塩にカプセル化するスケーラブルな乳化方法について説明します。この代替の方法により、細胞および炭酸カルシウムを含有するアルギネート液滴を鉱油中で乳化し、内部カルシウム放出およびイオノトロピックアルギン酸塩ゲル化をもたらすpHの低下によって低下した。現在の方法は、乳化の20分以内にアルギン酸ビーズの生成を可能にする。カプセル化工程に必要とされる装置は、大部分の実験室で利用可能な単純攪拌容器からなる。

Introduction

哺乳動物細胞のカプセル化は、免疫拒絶1から移植された細胞を保護する手段として、または固定化された細胞培養のための三次元支持体を提供するための手段として広く研究されている2,3,4 。アルギン酸ビーズ中の膵島封入は、同種異系の5,6または異種7,8,9,10,11,12齧歯類における糖尿病を逆転させるために使用されている。 1型糖尿病を治療するためのカプセル化された膵島移植の前臨床試験および臨床試験が進行中である13,14,15。移植用途またはより大きいスケールのためにインビトロで固定化された細胞生産では、ノズルベースのビーズ発生器が一般に使用される。典型的には、アルギン酸塩と細胞との混合物をノズルを通してポンプ輸送して、二価カチオンを含有する攪拌溶液に落ちる液滴を形成し、液滴の外部ゲル化をもたらす。同軸ガス流16,17 、ノズル振動18 、静電反発力19または回転ワイヤ20は、ノズル先端での液滴形成を容易にする。

従来のビーズ発生器の主な欠点は、スループットが限られていることと、十分なビード形成をもたらす溶液粘度の限定された範囲であることである21 。高い流速では、ノズルを出る流体は、ノズル直径よりも小さい液滴に砕かれ、サイズ制御を減少させる。スループットを向上させるためにマルチノズルビードジェネレータを使用できますが、ノズル間の流れの均一な分布と溶液> 0.2 Pasの使用は問題である22 。最後に、使用されるノズルの直径が100μmと500μmの間であり、人間の島の〜15%が200μmより大きくてもよいため、ノズルベースのデバイスのすべてが島にいくらかの損傷を与えると予想される。

このビデオでは、1滴ずつではなく、1回の乳化ステップで液滴を形成することによって、哺乳動物細胞をカプセル化する別の方法について説明します。ビーズ製造は単純な撹拌容器で行われるため、この方法は、設備コストが低くても、小(〜1mL)から大規模(10 3L範囲)のビーズ製造に適しています。この方法は、ビーズ生成時間が短い( 例えば、 20分間)広範囲のアルギン酸塩粘度を用いて、高い球形度を有するビーズの製造を可能にする。この方法はもともとPoncelet et all。 DNA27 、インスリン29を含むタンパク質28 、および細菌30を固定化するために使用された。私たちは、最近、これらの方法を、膵β細胞株31,32および一次膵臓組織32を用いた哺乳動物細胞のカプセル化に適用した。

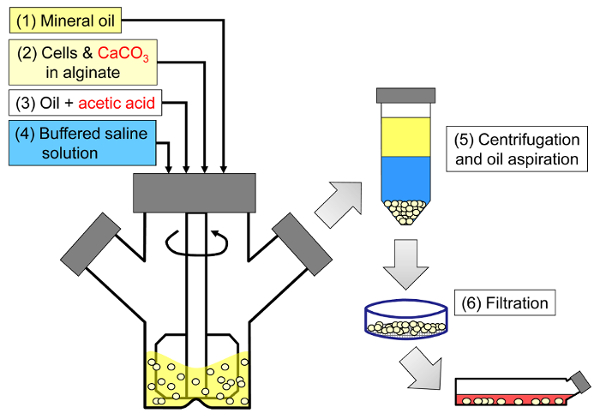

この方法の原理は、鉱油中のアルギネート液滴からなる油中水型エマルジョンを生成し、続いてアルギン酸塩液滴を内部でゲル化させることである( 図1 )。最初に、封入剤( 例えば、細胞)を、初期プロセスpHにおいて低い溶解度を有する微粒子カルシウム塩を含有するアルギン酸塩溶液に分散させる。次いで、アルギン酸塩混合物を撹拌した有機相に添加して、通常は界面活性剤。哺乳類細胞のカプセル化の場合、血清中に存在する成分は界面活性剤として作用することができる。次に、水相に分配する油溶性酸を添加することによってカルシウム塩を可溶化するためにpHを低下させる。鉱物油/水分配係数<0.005〜33を有する酢酸は、油中に予め溶解され、次いで乳濁液に添加され、油相中で混合され、水相34に急速に分配される。 図2は、酸性化および内部ゲル化工程中に起こる化学反応および拡散を示す。最後に、カプセル化された細胞は、転相、遠心分離によって加速された相分離、繰り返し洗浄工程および濾過によって回収される。次いで、これらの工程の後に、品質管理分析、 インビトロ細胞培養および/またはカプセル化細胞の移植のためのビーズおよび細胞サンプリングを行うことができる。

<p class = "jove_content" fo:keep-together.within-page = "1">

図1:哺乳動物細胞をカプセル化するための乳化に基づくプロセスの概略図。ビーズは、鉱油中のアルギン酸塩、細胞およびCaCO 3混合物を乳化させることによって(酢酸塩を添加することにより内部ゲル化を誘発する(工程3))、最初に製造される(工程1および工程2)。次いで、ゲル反転ビーズを水性緩衝液を添加して転相(工程4)、次に遠心分離および油吸引(工程5)、次いで濾過(工程6)を加えることにより、油から分離する。最後に、フィルター上に集められたビーズは、インビトロ培養または移植のために細胞培養培地に移される。 この図の拡大版を見るには、ここをクリックしてください。

<imgalt = "図2" class = "xfigimg" src = "/ files / ftp_upload / 55280 / 55280fig2.jpg" />

図2:内部ゲル化中に起こる反応および拡散ステップ。 (1)酢酸を有機相に添加し、対流によってアルギン酸塩小滴に輸送する。 (2)酢酸が水相に分配される。 (3)水の存在下では、酸が解離して拡散して濃青色のCaCO 3粒子に達する。 (4)H +イオンはCaCO 3中のCa 2+イオンと交換され、Ca 2+イオンを放出する。 (5)カルシウムイオンは、未反応アルギン酸塩に遭遇するまで拡散し、アルギン酸鎖のイオン化架橋をもたらす。 この図の拡大版を見るには、ここをクリックしてください。

従来のノズルベースの細胞カプセル化装置とは対照的に、広いビーズサイズ分布が達成される攪拌乳化における液滴形成のメカニズムのために、このプロセスから生じる。アプリケーションのサブセットでは、このビードサイズの分布に問題がある可能性があります。例えば、細胞のより大きな部分が、より小さいビーズのビーズ表面に露出され得る。栄養素( 例えば酸素)の制限が懸念される場合、これらの制限は、より大きなビーズで悪化する可能性がある。撹拌乳化法の利点は、平均ビーズサイズが、乳化工程の間の撹拌速度を変えることによって容易に調節できることである。広範なビーズサイズ分布は、カプセル化された細胞性能に対するビーズサイズの影響を研究するために利用することもできる。

乳化および内部ゲル化による哺乳動物細胞のカプセル化は、ビーズ発生器を備えていない研究室にとって興味深い代替物である。さらに、この方法は、処理時間を短縮するか、非常に低いまたは非常に高いアルギネート濃度でビーズを生成するという選択肢をユーザに与えるations。

10mMの4-(2-ヒドロキシエチル)-1-ピペラジンエタンスルホン酸(HEPES)緩衝液中で調製した10.5mLの5%アルギン酸溶液中に細胞をカプセル化する方法を下記に概説する。アルギン酸塩は、移植グレードLVM(低粘度高マンヌロン酸含量)およびMVG(中粘度高グルロン酸含量)アルギン酸塩の50:50混合物からなる。物理的架橋剤として、最終濃度24mMの炭酸カルシウムを使用する。軽質鉱物油は有機相を構成し、酢酸はエマルジョンを酸性化し、内部ゲル化を誘発するために使用される。しかしながら、選択されるアルギン酸塩の種類および組成、ならびにプロセス緩衝液は、所望の用途32に依存する。このプロトコールを用いて様々なアルギネート型(表の表を参照)を使用してビーズを作製した。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

内部ゲル化反応中の様々なステップ( 図2に図示)は、全体的な反応速度を制限する可能性がある。 〜2.5μmより大きい炭酸カルシウムの場合、炭酸塩の溶解速度は速度制限26,44であることが示されている。内部のカルシウム放出をもたらす酸性化段階もまた、細胞生存に影響を及ぼす重要なプロセス変数であることが示されている32 。したがって、内部ゲル化を…

Divulgazioni

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

乳化プロセスに関する彼女の敷設作業と技術サポートのためのLauren Wilkinsonに感謝します。 IgorLaçik博士、Timothy J. Kieffer博士、James D. Johnson博士のご協力とご協力に感謝いたします。 DiabèteQuébec、JDRF、ThéCell、CQMF、自然科学および工学研究評議会(NSERC)、ヒト膵島移植センターおよびベータ細胞再生センター、カナダの幹細胞ネットワーク、健康研究のためのマイケルスミス財団、財政的支援のためのCOST 865、そして自然保護技術のための財団法人である。

Materials

| Reagents and consumables | |||

| LVM alginate (transplantation-grade) | Novamatrix | Non-applicable | Referred to as "alginate #1" in the results. |

| MVG alginate (transplantation-grade) | Novamatrix | Non-applicable | Referred to as "alginate #2" in the results. |

| Alginate (cell culture-grade) | Sigma | A0682 (low viscosity) or A2033 (medium viscosity) | A2033 is referred to as "alginate #3" in the results. |

| DMEM | Life Technologies | 11995-065 | |

| Fetal bovine serum, characterized, Canadian origin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | SH3039603 | |

| Glutamine | Life Technologies | 25030 | |

| Penicillin and streptomycin | Sigma | P4333-100ML | |

| HEPES, cell culture tested | Sigma | H4034-100G | |

| NaCl | Thermo Fisher Scientific | S271-1 | |

| Fine-grain CaCO3 | Avantor Materials | 1301-01 | After preparing the CaCO3 suspension, sonicate and use within one month. |

| Light mineral oil | Thermo Fisher Scientific | O121-4 | Sterile filter through a 0.22 μm pore size membrane prior to use. |

| Glacial acetic acid | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A38-500 | Handle with caution: refer to MSDS. |

| Sterile spatulas | Sigma | CLS3004-100EA | |

| Sterile nylon cell strainers, 40 µm | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 08-771-1 | |

| Serological pipettes (2 mL, 5 mL, 10 mL, 25 mL) | Sarstedt | 86.1252.001, 86.1253.001, 86.1254.001 and 86.1685.001 | |

| Pasteur pipettes | VWR | 14673-043 | |

| Toluidine Blue-O | Sigma | T3260 | |

| Equipment | |||

| 100 mL microcarrier spinner flasks | Bellco | 1965-00100 | The impeller configuration with recent models may not be suitable for adequate emulsification. A blade able to sweep the oil down to 0.5 cm from the bottom of the flask can be custom-made from a Teflon sheet. |

| Magnetic stir plate with adjustable speed | Bellco | 7760-06005 | The rotation speed should be calibrated (e.g. using a tachometer) prior to use. |

| Cell counter | Innovatis | Cedex AS20 | This system is now sold by Roche. This automated cell counter can also be replaced by manual cell enumeration after Trypan blue staining using a hemocytometer. |

| LED light box | Artograph | LightPad® PRO | This item can be replaced by other types of illuminators. |

| Handheld camera | Canon | PowerShot A590 IS | A variety of handheld cameras can be used to capture toluidine blue-o stained bead images. A ruler should be placed next to the Petri dish containing the beads prior to acquiring images. |

| Fluorescence microscope with phase contrast and adequate fluorescence filters | Olympus | IX81 | Several microscopy systems were used to image the beads. The results shown here were obtained with an IX81 microscope equipped with GFP and TRITC fluorescence filters. To capture entire beads, 4X to 20X objectives were used depending on the agitation rate. Live/dead staining images were typically captured with 20X to 40X objectives. |

| Image aquisition software | Molecular Devices | Metamorph | A variety of image acquisition software can be used to acquire phase contrast and fluorescence images. |

| Image analysis freeware | CellProfiler | Non-applicable | A variety of image analysis software can be used to identify beads as objects and analyze bead size (e.g. ImageJ). |

Riferimenti

- Scharp, D. W., Marchetti, P. Encapsulated islets for diabetes therapy: history, current progress, and critical issues requiring solution. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 67-68, 35-73 (2014).

- Chayosumrit, M., Tuch, B., Sidhu, K. Alginate microcapsule for propagation and directed differentiation of hESCs to definitive endoderm. Biomaterials. 31 (3), 505-514 (2010).

- Sidhu, K., Kim, J., Chayosumrit, M., Dean, S., Sachdev, P. Alginate microcapsule as a 3D platform for propagation and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESC) to different lineages. J Vis Exp. (61), (2012).

- Tostoes, R. M., et al. Perfusion of 3D encapsulated hepatocytes–a synergistic effect enhancing long-term functionality in bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 108 (1), 41-49 (2011).

- Duvivier-Kali, V. F., Omer, A., Parent, R. J., O’Neil, J. J., Weir, G. C. Complete protection of islets against allorejection and autoimmunity by a simple barium-alginate membrane. Diabetes. 50 (8), 1698-1705 (2001).

- Omer, A., et al. Long-term normoglycemia in rats receiving transplants with encapsulated islets. Transplantation. 79 (1), 52-58 (2005).

- Rayat, G. R., Rajotte, R. V., Ao, Z., Korbutt, G. S. Microencapsulation of neonatal porcine islets: protection from human antibody/complement-mediated cytolysis in vitro and long-term reversal of diabetes in nude mice. Transplantation. 69 (6), 1084-1090 (2000).

- Korbutt, G. S., Mallett, A. G., Ao, Z., Flashner, M., Rajotte, R. V. Improved survival of microencapsulated islets during in vitro culture and enhanced metabolic function following transplantation. Diabetologia. 47 (10), 1810-1818 (2004).

- Luca, G., et al. Improved function of rat islets upon co-microencapsulation with Sertoli’s cells in alginate/poly-L-ornithine. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2 (3), E15 (2001).

- Omer, A., et al. Survival and maturation of microencapsulated porcine neonatal pancreatic cell clusters transplanted into immunocompetent diabetic mice. Diabetes. 52 (1), 69-75 (2003).

- Schneider, S., et al. Long-term graft function of adult rat and human islets encapsulated in novel alginate-based microcapsules after transplantation in immunocompetent diabetic mice. Diabetes. 54 (3), 687-693 (2005).

- Cui, H., et al. Long-term metabolic control of autoimmune diabetes in spontaneously diabetic nonobese diabetic mice by nonvascularized microencapsulated adult porcine islets. Transplantation. 88 (2), 160-169 (2009).

- Krishnan, R., Alexander, M., Robles, L., Foster, C. E., Lakey, J. R. Islet and stem cell encapsulation for clinical transplantation. Rev Diabet Stud. 11 (1), 84-101 (2014).

- Robles, L., Storrs, R., Lamb, M., Alexander, M., Lakey, J. R. Current status of islet encapsulation. Cell Transplant. 23 (11), 1321-1348 (2014).

- Desai, T., Shea, L. D. Advances in islet encapsulation technologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. , (2016).

- Anilkumar, A. V., Lacik, I., Wang, T. G. A novel reactor for making uniform capsules. Biotechnol Bioeng. 75 (5), 581-589 (2001).

- Wolters, G. H., Fritschy, W. M., Gerrits, D., van Schilfgaarde, R. A versatile alginate droplet generator applicable for microencapsulation of pancreatic islets. J Appl Biomater. 3 (4), 281-286 (1991).

- Heinzen, C., Marison, I., Berger, A., von Stockar, U. Use of vibration technology for jet break-up for encapsulation of cells, microbes and liquids in monodisperse microcapsules. Practical Aspects of Encapsulation Technologies. , 19-25 (2002).

- Poncelet, D., et al. A Parallel plate electrostatic droplet generator: Parameters affecting microbead size. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 42 (2-3), 251-255 (1994).

- Prüße, U., Dalluhn, J., Breford, J., Vorlop, K. D. Production of Spherical Beads by JetCutting. Chemical Engineering & Technology. 23 (12), 1105-1110 (2000).

- Hoesli, C. A. . Bioprocess development for the cell-based treatment of diabetes (PhD thesis). , (2010).

- Brandenberger, H., Widmer, F. A new multinozzle encapsulation/immobilisation system to produce uniform beads of alginate. J Biotechnol. 63 (1), 73-80 (1998).

- Merani, S., Toso, C., Emamaullee, J., Shapiro, A. M. Optimal implantation site for pancreatic islet transplantation. Br J Surg. 95 (12), 1449-1461 (2008).

- Reis, C. P., Neufeld, R. J., Vilela, S., Ribeiro, A. J., Veiga, F. Review and current status of emulsion/dispersion technology using an internal gelation process for the design of alginate particles. J Microencapsul. 23 (3), 245-257 (2006).

- Poncelet, D., et al. Production of alginate beads by emulsification/internal gelation. I. Methodology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 38 (1), 39-45 (1992).

- Poncelet, D., et al. Production of alginate beads by emulsification/internal gelation. II. Physicochemistry. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 43 (4), 644-650 (1995).

- Alexakis, T., et al. Microencapsulation of DNA within alginate microspheres and crosslinked chitosan membranes for in vivo application. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 50 (1), 93-106 (1995).

- Vandenberg, G. W., De La Noue, J. Evaluation of protein release from chitosan-alginate microcapsules produced using external or internal gelation. J Microencapsul. 18 (4), 433-441 (2001).

- Silva, C. M., Ribeiro, A. J., Figueiredo, I. V., Goncalves, A. R., Veiga, F. Alginate microspheres prepared by internal gelation: development and effect on insulin stability. Int J Pharm. 311 (1-2), 1-10 (2006).

- Larisch, B. C., Poncelet, D., Champagne, C. P., Neufeld, R. J. Microencapsulation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. J Microencapsul. 11 (2), 189-195 (1994).

- Hoesli, C. A., et al. Reversal of diabetes by betaTC3 cells encapsulated in alginate beads generated by emulsion and internal gelation. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 100 (4), 1017-1028 (2012).

- Hoesli, C. A., et al. Pancreatic cell immobilization in alginate beads produced by emulsion and internal gelation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 108 (2), 424-434 (2011).

- Reinsel, M. A., Borkowski, J. J., Sears, J. T. Partition Coefficients for Acetic, Propionic, and Butyric Acids in a Crude Oil/Water System. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 39 (3), 513-516 (1994).

- Xiu-Dong, L., Wei-Ting, Y., Jun-Zhang, L., Xiao-Jun, M., Quan, Y. Diffusion of acetic acid across oil/water interface in emulsification-internal gelation process for preparation of alginate gel beads. Chemical Research in Chinese Universities. 23 (5), 579-584 (2007).

- Fernandez, S. A., et al. Emulsion-based islet encapsulation: predicting and overcoming islet hypoxia. Bioencapsulation Innovations. (220), 14-15 (2014).

- Carpenter, A. E., et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7 (10), R100 (2006).

- Hinze, J. O. Fundamentals of the hydrodynamic mechanism of splitting in dispersion processes. AIChE Journal. 1 (3), 289-295 (1955).

- Kolmogorov, A. N. On the breakage of drops in a turbulent flow (translated from Russian). Doklady Akademii Nauk. 66, 825-828 (1949).

- Davies, J. T. Drop Sizes of Emulsions Related to Turbulent Energy-Dissipation Rates. Chemical Engineering Science. 40 (5), 839-842 (1985).

- Pacek, A. W., Chamsart, S., Nienow, A. W., Bakker, A. The influence of impeller type on mean drop size and drop size distribution in an agitated vessel. Chemical Engineering Science. 54 (19), 4211-4222 (1999).

- Steiner, H., et al. Numerical simulation and experimental study of emulsification in a narrow-gap homogenizer. Chemical Engineering Science. 61 (17), 5841-5855 (2006).

- Tcholakova, S., Denkov, N. D., Lips, A. Comparison of solid particles, globular proteins and surfactants as emulsifiers. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 10 (12), 1608-1627 (2008).

- Lagisetty, J. S., Das, P. K., Kumar, R., Gandhi, K. S. Breakage of viscous and non-Newtonian drops in stirred dispersions. Chemical Engineering Science. 41 (1), 65-72 (1986).

- Draget, K. I., Ostgaard, K., Smidsrod, O. Homogeneous Alginate Gels – a Technical Approach. Carbohydrate Polymers. 14 (2), 159-178 (1990).

- Poncelet, D., Dulieu, C., Jacquot, M., Wijffels, R. H. . Immobilized Cells. , 15-30 (2001).

- Islam, A. W., Zavvadi, A., Kabadi, V. N. Analysis of Partition Coefficients of Ternary Liquid-Liquid Equilibrium Systems and Finding Consistency Using Uniquac Model. Chemical and Process Engineering-Inzynieria Chemiczna I Procesowa. 33 (2), 243-253 (2012).

- Quong, D., Neufeld, R. J., Skjak-Braek, G., Poncelet, D. External versus internal source of calcium during the gelation of alginate beads for DNA encapsulation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 57 (4), 438-446 (1998).

- De Vos, P., De Haan, B. J., Van Schilfgaarde, R. Upscaling the production of microencapsulated pancreatic islets. Biomaterials. 18 (16), 1085-1090 (1997).

- Gross, J. D., Constantinidis, I., Sambanis, A. Modeling of encapsulated cell systems. J Theor Biol. 244 (3), 500-510 (2007).