Utilisation d’un dispositif d’assistance ventriculaire percutanée / système de pontage de l’oreillette gauche à l’artère fémorale pour le choc cardiogénique

Summary

L’article suivant décrit la procédure par étapes pour la mise en place d’un dispositif (par exemple, Tandemheart) en choc cardiogénique (CS) qui est un dispositif d’assistance ventriculaire gauche percutané (pLVAD) et un système de pontage auriculaire gauche à l’artère fémorale (LAFAB) qui contourne et soutient le ventricule gauche (LV) dans le CS.

Abstract

Le système de pontage auriculaire gauche à fémoral (LAFAB) est un dispositif de soutien circulatoire mécanique (MCS) utilisé dans le choc cardiogénique (CS) qui contourne le ventricule gauche en drainant le sang de l’oreillette gauche (LA) et en le renvoyant dans la circulation artérielle systémique via l’artère fémorale. Il peut fournir des débits allant de 2,5 à 5 L / min en fonction de la taille de la canule. Ici, nous discutons du mécanisme d’action du LAFAB, des données cliniques disponibles, des indications de son utilisation dans le choc cardiogénique, des étapes d’implantation, des soins post-procéduraux et des complications associées à l’utilisation de ce dispositif et à leur prise en charge.

Nous fournissons également une brève vidéo de la composante procédurale de la thérapie par dispositif, y compris la préparation pré-placement, la mise en place percutanée de l’appareil par ponction transseptale sous guidage échocardiographique et la gestion postopératoire des paramètres de l’appareil.

Introduction

Le choc cardiogénique (CS) est un état d’hypoperfusion tissulaire avec ou sans hypotension concomitante, dans lequel le cœur est incapable de fournir suffisamment de sang et d’oxygène pour répondre aux demandes du corps, entraînant une défaillance d’organe. Il est classé en stades A à E par la Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI): stade A – patients à risque de CS; stade B – patients au stade précoce de la CS avec hypotension ou tachycardie sans hypoperfusion; stade C – CS classique avec phénotype froid et humide nécessitant des inotropes / vasopresseurs ou un soutien mécanique pour maintenir la perfusion; stade D – détérioration du support médical ou mécanique actuel nécessitant une escalade vers des dispositifs plus avancés; et stade E – comprend les patients présentant un collapsus circulatoire et des arythmies réfractaires qui subissent activement un arrêt cardiaque avec réanimation cardiorespiratoire en cours1. Les causes les plus courantes de CS sont l’IM aiguë (AMI) représentant 81 % des cas dans une analyse récemment rapportée2, et l’insuffisance cardiaque aiguë décompensée (ADHF). Le CS est classiquement caractérisé par une congestion et une altération de la perfusion, qui se manifestent par des pressions de remplissage élevées (pression de coin capillaire pulmonaire [PCWP], pression diastolique terminale ventriculaire gauche [LVEDP], pression veineuse centrale [CVP] et pression diastolique terminale ventriculaire droite [RVEDP]), diminution du débit cardiaque (CO), de l’indice cardiaque (IC), de la puissance cardiaque (CPO) et dysfonctionnement de l’organe final3 . Dans le passé, les seuls traitements disponibles pour l’AMI compliquée par la CS étaient la revascularisation précoce et la prise en charge médicale avec des inotropes et/ou des vasopresseurs4. Plus récemment, avec l’avènement des dispositifs de soutien circulatoire mécanique (MCS) et la reconnaissance que l’escalade des vasopresseurs est associée à une mortalité accrue, il y a eu un changement de paradigme dans le traitement de l’AMI et de l’ADHF CS5,6.

À l’ère actuelle des dispositifs d’assistance ventriculaire percutanée (pVAD), il existe un certain nombre de plates-formes /configurations de dispositifs MCS disponibles, qui fournissent un soutien circulatoire et ventriculaire univentriculaire ou biventriculaire avec et sans capacité d’oxygénation7. Malgré l’augmentation constante de l’utilisation des DAEP pour traiter à la fois l’AMI et l’ADHF CS, les taux de mortalité sont restés en grande partie inchangés5. Avec les nouvelles preuves des avantages cliniques possibles du déchargement précoce du ventricule gauche (LV) dans AMI8 et l’utilisation précoce de MCS dans AMI CS9, l’utilisation de MCS continue d’augmenter.

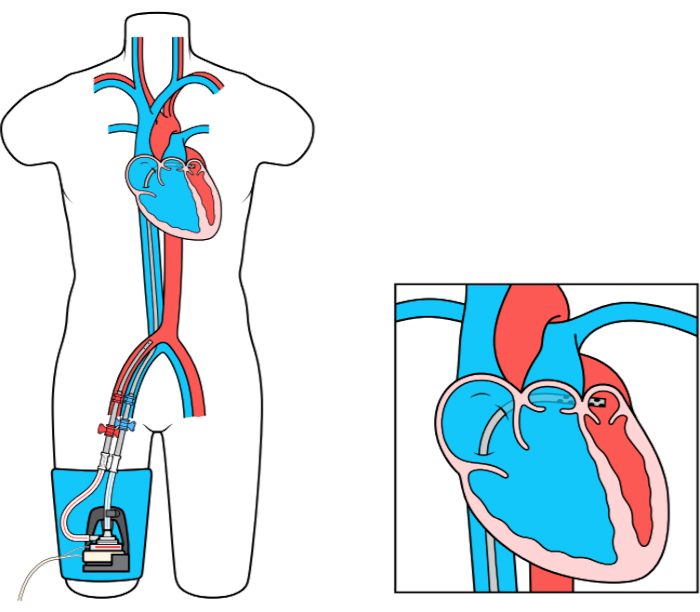

Le dispositif MCS LAFAB (Left Atrial to Femoral Artery Bypass) contourne le LV en drainant le sang de l’oreillette gauche (LA) et en le renvoyant dans la circulation artérielle systémique via l’artère fémorale (Figure 1). Il est soutenu par une pompe centrifuge externe qui offre un débit de 2,5 à 5,0 litres par minute (L / m) (pompe de nouvelle génération, désignée LifeSPARC, capable d’un débit allant jusqu’à 8 L / m) en fonction de la taille des canules. Une fois que le sang est extrait de l’AL via la canule veineuse transseptale, il passe à travers la pompe centrifuge externe qui recircule le sang dans le corps du patient via la canule artérielle placée dans l’artère fémorale.

Figure 1 : configuration de LAFAB. Image reproduite avec l’aimable autorisation de TandemLife, une filiale en propriété exclusive de LivaNova US Inc. Veuillez cliquer ici pour voir une version agrandie de ce chiffre.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

Hémodynamique du dispositif LAFAB:

Le profil hémodynamique du dispositif LAFAB est distinct des autres pVAD. En drainant le sang directement de l’AL et en le renvoyant dans l’artère fémorale, l’appareil contourne complètement le LV. Ce faisant, il réduit le volume et la pression diastoliques de fin de LV, contribuant à améliorer la géométrie de LV et entraînant ainsi une diminution du travail de course LV. Cependant, en renvoyant le sang dans l’artère iliaque / aor…

Divulgazioni

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

À l’équipe TandemHeart de LifeSparc.

Materials

| For LAFAB (TandemHeart) | |||

| Factory Supplied Equipment for circuit connections. | TandemLife | ||

| ProtekSolo 15 Fr or 17 Fr Arterial Cannula | TandemLife | ||

| ProtekSolo 62 cm or 72 cm Transseptal Cannula | TandemLife | ||

| TandemHeart Controller | TandemLife | For adjusting flows/RPM | |

| TandemHeart Pump | LifeSPARC | Centrifugal pump | |

| For RAPAB (ProtekDuo) | |||

| Factory Supplied Equipment to complete the circuit. | TandemLife | ||

| ProtekDuo 29 Fr or 31 Fr Dual Lumen Cannula | TandemLife | ||

| TandemHeart Controller | TandemLife | For adjusting flows/RPM | |

| TandemHeart Pump | LifeSPARC | Centrifugal pump |

Riferimenti

- Baran, D. A., et al. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 94 (1), 29-37 (2019).

- Harjola, V. -. P., et al. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. European Journal of Heart Failure. 17 (5), 501-509 (2015).

- Furer, A., Wessler, J., Burkhoff, D. Hemodynamics of Cardiogenic Shock. Interventional Cardiology Clinics. 6 (3), 359-371 (2017).

- Hochman, J. S., et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction–etiologies, management and outcome: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 36 (3), 1063-1070 (2000).

- Shah, M., et al. Trends in mechanical circulatory support use and hospital mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction and non-infarction related cardiogenic shock in the United States. Clinical Research in Cardiology. 107 (4), 287-303 (2018).

- van Diepen, S., et al. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 136 (16), 232-268 (2017).

- Alkhouli, M., et al. Mechanical Circulatory Support in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 22 (2), 4 (2020).

- Basir, M. B., et al. Feasibility of early mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: The Detroit cardiogenic shock initiative. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 91 (3), 454-461 (2018).

- Basir, M. B., et al. Improved Outcomes Associated with the use of Shock Protocols: Updates from the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 93 (7), 1173-1183 (2019).

- Alkhouli, M., Rihal, C. S., Holmes, D. R. Transseptal Techniques for Emerging Structural Heart Interventions. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 9 (24), 2465-2480 (2016).

- Dennis, C., et al. Clinical use of a cannula for left heart bypass without thoracotomy: experimental protection against fibrillation by left heart bypass. Annals of Surgery. 156 (4), 623-637 (1962).

- Dennis, C., et al. Left atrial cannulation without thoracotomy for total left heart bypass. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. 123, 267-279 (1962).

- Fonger, J. D., et al. Enhanced preservation of acutely ischemic myocardium with transseptal left ventricular assist. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 57 (3), 570-575 (1994).

- Thiele, H., et al. Reversal of cardiogenic shock by percutaneous left atrial-to-femoral arterial bypass assistance. Circulation. 104 (24), 2917-2922 (2001).

- Burkhoff, D., et al. A randomized multicenter clinical study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device versus conventional therapy with intraaortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock. American Heart Journal. 152 (3), 469 (2006).

- Thiele, H., et al. Randomized comparison of intra-aortic balloon support with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with revascularized acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. European Heart Journal. 26 (13), 1276-1283 (2005).

- Gregoric, I. D., et al. TandemHeart as a rescue therapy for patients with critical aortic valve stenosis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 88 (6), 1822-1826 (2009).

- Kar, B., et al. The percutaneous ventricular assist device in severe refractory cardiogenic shock. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 57 (6), 688-696 (2011).

- Patel, C. B., Alexander, K. M., Rogers, J. G. Mechanical Circulatory Support for Advanced Heart Failure. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 12 (6), 549-565 (2010).

- Tempelhof, M. W., et al. Clinical experience and patient outcomes associated with the TandemHeart percutaneous transseptal assist device among a heterogeneous patient population. Asaio Journal. 57 (4), 254-261 (2011).

- Gregoric, I. D., et al. The TandemHeart as a bridge to a long-term axial-flow left ventricular assist device (bridge to bridge). Texas Heart Institute Journal. 35 (2), 125-129 (2008).

- Bruckner, B. A., et al. Clinical experience with the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device as a bridge to cardiac transplantation. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 35 (4), 447-450 (2008).

- Agarwal, R., et al. Successful treatment of acute left ventricular assist device thrombosis and cardiogenic shock with intraventricular thrombolysis and a tandem heart. Asaio Journal. 61 (1), 98-101 (2015).

- Vetrovec, G. W. Hemodynamic Support Devices for Shock and High-Risk PCI: When and Which One. Current Cardiology Reports. 19 (10), 100 (2017).

- Al-Husami, W., et al. Single-center experience with the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device to support patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 20 (6), 319-322 (2008).

- Vranckx, P., et al. Clinical introduction of the Tandemheart, a percutaneous left ventricular assist device, for circulatory support during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. International Journal of Cardiovascular Interventions. 5 (1), 35-39 (2003).

- Vranckx, P., et al. The TandemHeart, percutaneous transseptal left ventricular assist device: a safeguard in high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions. The six-year Rotterdam experience. Euro Intervention. 4 (3), 331-337 (2008).

- Vranckx, P., et al. Assisted circulation using the TandemHeart during very high-risk PCI of the unprotected left main coronary artery in patients declined for CABG. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 74 (2), 302-310 (2009).

- Thomas, J. L., et al. Use of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device for high-risk cardiac interventions and cardiogenic shock. Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 22 (8), 360 (2010).

- Vranckx, P., et al. Assisted circulation using the Tandemhear , percutaneous transseptal left ventricular assist device, during percutaneous aortic valve implantation: the Rotterdam experience. Euro Intervention. 5 (4), 465-469 (2009).

- Pitsis, A. A., et al. Temporary assist device for postcardiotomy cardiac failure. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 77 (4), 1431-1433 (2004).

- Singh, G. D., Smith, T. W., Rogers, J. H. Targeted Transseptal Access for MitraClip Percutaneous Mitral Valve Repair. Interventional Cardiology Clinics. 5 (1), 55-69 (2016).

- Subramaniam, A. V., et al. Complications of Temporary Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support for Cardiogenic Shock: An Appraisal of Contemporary Literature. Cardiology and Therapy. 8 (2), 211-228 (2019).

- Morley, D., et al. Hemodynamic effects of partial ventricular support in chronic heart failure: Results of simulation validated with in vivo data. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 133 (1), 21-28 (2007).

- Naidu, S. S. Novel Percutaneous Cardiac Assist Devices. Circulation. 123 (5), 533-543 (2011).

- Kapur, N. K., et al. Hemodynamic Effects of Left Atrial or Left Ventricular Cannulation for Acute Circulatory Support in a Bovine Model of Left Heart Injury. ASAIO Journal. 61 (3), 301-306 (2015).

- Smith, L., et al. Outcomes of patients with cardiogenic shock treated with TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device: Importance of support indication and definitive therapies as determinants of prognosis. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 92 (6), 1173-1181 (2018).

- Ergle, K., Parto, P., Krim, S. R. Percutaneous Ventricular Assist Devices: A Novel Approach in the Management of Patients With Acute Cardiogenic Shock. The Ochsner Journal. 16 (3), 243-249 (2016).

- Sultan, I., Kilic, A., Kilic, A.Short-Term Circulatory and Right Ventricle Support in Cardiogenic Shock: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Tandem Heart, CentriMag, and Impella. Heart Failure Clinics. 14 (4), 579-583 (2018).

- Bermudez, C., et al. . Percutaneous right ventricular support: Initial experience from the tandemheart experiences and methods (THEME) registry. , (2018).

- Aggarwal, V., Einhorn, B. N., Cohen, H. A. Current status of percutaneous right ventricular assist devices: First-in-man use of a novel dual lumen cannula. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 88 (3), 390-396 (2016).

- Kapur, N. K., et al. Mechanical circulatory support devices for acute right ventricular failure. Circulation. 136 (3), 314-326 (2017).

- Kapur, N. K., et al. Mechanical Circulatory Support for Right Ventricular Failure. JACC: Heart Failure. 1 (2), 127-134 (2013).

- Geller, B. J., Morrow, D. A., Sobieszczyk, P. Percutaneous Right Ventricular Assist Device for Massive Pulmonary Embolism. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 5 (6), 74-75 (2013).

- Bhama, J., et al. Initial Experience with a Percutaneous Dual Lumen Single Cannula Strategy for Temporary Right Ventricular Assist Device Support Following Durable LVAD Therapy. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 35 (4), 323 (2013).

- O’Neill, B., et al. Right ventricular hemodynamic support with the PROTEKDuo Cannula. Initial experience from the tandemheart experiences and methods (THEME) registry category. Miscellaneous. , (2018).

- O’Brien, B., et al. Fluoroscopy-free AF ablation using transesophageal echocardiography and electroanatomical mapping technology. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology. 50 (3), 235-244 (2017).

- O’Brien, B., et al. Transseptal puncture — Review of anatomy, techniques, complications and challenges. International Journal of Cardiology. 233, 12-22 (2017).