覚醒、認知的不協和の誤

English

Condividere

Panoramica

ソース: ピーター マンド Siedlecki & ジェイ ・ ヴァン ・ Bavel-ニューヨーク大学

心理学研究のホストでは、心理的な覚醒感が比較的あいまいになるし、特定の状況下で導くことができます私たち自身の精神状態について不正確な結論を作ることを示唆しています。この作業の多くはスタンレー ・ シャクターによる種子研究から流れると、ジェローム ・ シンガー。覚醒を経験する誰か明らかに、適切な説明がない場合は、状況や社会的文脈の他の面で自分の覚醒を説明しよう可能性があります。

たとえば、1 つの古典的な研究では参加者は自分たちのビジョンをテストする薬と呼ばれる“Suproxin“の試みで受け取っていたと言われました。1現実には、彼らは通常心理的な覚醒感を増加エピネフリンのショットを受け取った。いくつかの参加者は、薬はエピネフリンのような副作用がある言われた、他の人は副作用を知らされていなかった、他の人が誤解された、喚起の副作用なしでプラセボ投与を受けた他の人。南部連合と参加者の交流、人のいずれかの陶酔や怒っている方法で動作しました。覚醒 (例えば、知らされていない状態) の彼らの感じを説明していた参加者が南軍に最も敏感が検討を行った。つまり、これらの参加者を (幸福感または怒り) の共犯者‘感情に最も強く取った。

その後の研究では、自然環境における対人魅力のドメインにこの効果を一般化しました。2研究者高、狭い吊り橋 (高覚醒)、または (低覚醒) より低いより安定した橋を渡って歩いて魅力的な女性実験者を満たす男性の参加がありました。参加者があいまいな画像を説明に求められたアンケートを完了した後、実験者は、彼らは彼らはそれ以上の質問を持っていた場合を呼び出すように指示された彼女の電話番号とそれらを提供しました。特に、喚起の吊り橋を渡って歩いて男性が多くの性的コンテンツを説明を提供、彼らは調査の後、実験者を呼び出す可能性が高く。著者らは、これらの男性が misattributed を女性実験者との相互作用する橋交差点から生じる心理的覚醒とその後彼女の方の魅力の印としての覚醒を解釈を締結しました。

Zanna、たる製造人 (1974 年)3認知的不協和の研究にこれらの原則を適用されます。彼らは予測認知的不協和が発生するが、いくつかの他の外部影響に向かって心理的な覚醒を属性することができます人が外部の説明のソースを欠いている人々 と比較して、トピックについての態度を変更する可能性が低くなります。この作品は、以前の研究の伝統認知的不協和にレオン ・ フェスティンガーによる不協和音自体に不快感や緊張感として経験することが心理的に興奮させる現象があることを示唆し、1962 年に。4

Principi

Procedura

Risultati

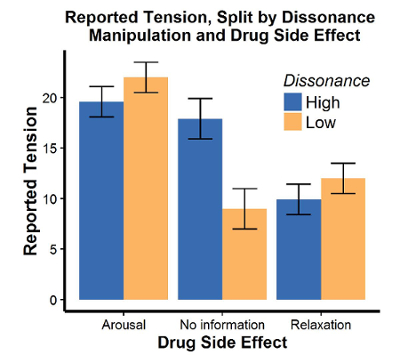

In the original investigation, the authors observed that participants’ reports of tension were influenced by the side effects that the experimenters ascribed to the drug (Figure 1). Participants in the arousal condition felt more tense than participants in the no-information condition, while participants in the relaxation condition would make them feel relaxed felt less tense than participants in the no-information condition. Moreover, within the no-information condition, participants in the high-choice condition reported feeling more tense than participants in the low-choice condition.

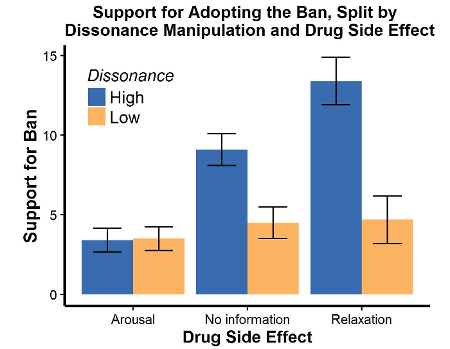

With regards to the attitude change results, the authors observed the classic dissonance result in the no-information condition: Participants in the high-choice condition showed larger changes in their attitudes than participants in the low-choice condition (Figure 2). However, in the arousal condition, there were no differences in attitude change between high- and low-choice. Conversely, in the relaxation condition, the effects of dissonance were exaggerated: Individuals in the high-choice condition showed even stronger evidence of attitude change, compared to low-choice participants.

Figure 1: Reported tension as a function of dissonance manipulation and drug side effect. Participants’ reported feelings of tension are plotted on the y-axis, as a function of both the dissonance manipulation they were exposed to and description of the drug’s side effects that they were given. Confirming the side effects manipulation, participants who were told the drug would make them feel aroused felt more tense than participants in the no-information condition, while participants who were told the drug would make them feel relaxed felt less tense than participants in the no-information condition. Moreover, within the no-information condition, participants in the high dissonance condition felt more tension than those in the low dissonance condition.

Figure 2: Support for adopting the ban as a function of dissonance manipulation and drug side effect. Participants’ support for adopting a ban on inflammatory speakers is plotted on the y-axis, as a function of both the dissonance manipulation they were exposed to and description of the drug’s side effects that they were given. The figure shows an interaction between the dissonance manipulation and the side effects ascribed to the drug. While participants who could attribute their arousal to the drug showed no support for the ban in either dissonance condition, participants in the no information condition showed stronger support for the ban in the high dissonance condition than in the low dissonance condition. Furthermore, when participants expected the drug to produce relaxation as a side effect, this effect of the high dissonance condition was even more pronounced.

Applications and Summary

Based on these results, the authors concluded that dissonance is, indeed, a psychologically arousing, drive-like mental state. As such, offering participants an external cue to ascribe their arousal to (in this case, the drug, as it was described in the arousal condition) reduced feelings of dissonance, and as a result, diminished the degree to which participants changed their attitudes. While the procedure described above has been employed here specifically as a means for studying cognitive dissonance, it could be modified to serve as a general method for inducing feelings of arousal, and more specifically, for examining the misattribution of arousal.

The overarching implication of studies like the one conducted by Zanna and Cooper in 1974 is that we are profoundly influenced by aspects of “the situation.” Why we may think that we know how we feel (and why we feel it) at any given moment, our mental states are a product of myriad external and internal factors. If you want to avoid feeling nervous before a crucial job interview, maybe avoid the (potentially) arousing cup of coffee. Conversely, perhaps taking a first date to a scary movie will cause them to misinterpret their racing heart rate as a sign of attraction.

More specifically with regards to the science of persuasion, this research suggests that psychological discomfort is a necessary condition for an individual to change their minds with respect to a given belief. Moreover, for attitude change to occur, it may be crucial to ensure that the individual is not able to attribute this discomfort to some other environmental attribute.

Riferimenti

- Schachter, S., & Singer, J. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review, 69, 379-399.

- Dutton, D. G., & Aron, A. P. (1974). Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 510-517.

- Zanna, M. P., & Cooper, J. (1974). Dissonance and the pill: An attribution approach to studying the arousal properties of dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 703-709.

- Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231-259.

Trascrizione

We may think that we know how and why we feel a certain way at any given moment. However, mental states are a product of both internal dispositions and external situations that we are not directly aware, which— under certain circumstances—creates inconsistencies between perceptual expectations and reality.

For example, while hiking an individual approaches a high and narrow suspension bridge and must cross it. In doing so, he is psychologically aroused, even though he doesn’t realize it. Instead, he interprets his feelings of excitement in terms of other salient aspects of the situation—like meeting a woman on the other side.

In this particular setting, he misattributed his arousal as a sign of attraction towards the female rather than the true cause—the bridge-crossing. Thus, the misattribution led to attraction and his pursuit of daringly exchanging his phone number.

However, if before scheduling the hiking trip he was committed to being single, such an action would be inconsistent with his own expectations, which is an example of cognitive dissonance—a state of mental distress related to simultaneously holding contradictory beliefs. This psychological conflict produces discomfort and as a result, could cause the individual to avoid relationship situations in the future.

This video demonstrates how to manipulate principles behind the two-factor theory of emotion—that feelings are a constructed product and therefore vulnerable to misinterpretation—and cognitive dissonance to ultimately measure attitudes about a particular belief, such as banning inflammatory speakers.

In this experiment, participants think they are completing a memory recall study—one that is supposed to examine a drug’s effect—when in fact, they are being manipulated. In reality, the pill is a placebo—an external cue—to attribute their internal feelings towards when writing a counter-attitudinal essay in the second phase.

During the first phase, participants are randomly divided into three groups: two are informed of the drug’s side effects—its absorption can result in either tenseness or relaxation—while the remaining third is not given any such information.

In the second phase—dissonance manipulation—participants are further divided into one of two levels: high-choice, where they can decide whether or not to write an essay that counters their beliefs about free speech on campus; or low-choice, where they are essentially forced to write it.

All participants are instructed to write the strongest and most forceful essay that they can in support of banning inflammatory speakers from campus. Those with freedom—high-choice—are reminded that they are under no obligation to take part.

Subsequently, the following dependent variables are measured using two attitude questionnaires: In the first, participants’ report their current feelings on a scale ranging from 1 (calm) to 31 (tense).

Compared to the no-information participants, those in the arousal condition are predicted to report being more tense, whereas those in the relaxed condition are expected to be the opposite—calmer. Such findings would be consistent with the original side effects provided.

Moreover, if cognitive dissonance is arousing, participants within the high-level, no-information group are expected to report being more tense than those assigned to the low-level.

In the second survey, participants are asked about their support for the adoption of the ban, on a scale from 1 (strongly opposed) to 31 (strongly in favor). For participants in the control no-information group—who had nothing to attribute their action on the essay to—those within the high-choice level are predicted to show a bigger attitude change, agreeing with the ban, compared to the low-choice level.

In addition, participants in the arousal condition are expected to attribute their tenseness to the pill and not the essay, so their attitudes of not agreeing to the ban wouldn’t change.

On the contrary, in the relaxation condition, there would be increased cognitive dissonance with a high-choice level, yielding an even bigger change in attitudes in favor of the ban, compared to the low-choice level.

Before starting the experiment, conduct a power analysis to determine the appropriate number of participants required. Once completed, greet each one in the lab and explain the cover story: that they will participate in a study on a drug’s effect on memory processes.

In the testing room, first instruct them to partake in a recall task on the computer. Display 12 nonsense words, each for a few seconds. Afterwards, prompt them to recall as many as possible.

Following the memory test, hand the participant a glass of water and a pill. From a stack of randomly ordered assignments, provide them a consent form to look over and sign before ingesting the pill. Note that the form indicates different side effects depending on the experimental conditions.

Here, the arousal assignment indicates that a reaction of tenseness is produced. For the second group, replace tenseness with relaxation. Lastly, in the no-information condition, simply indicate the absorption time and that there are no side effects. Once signed, allow the participant to ingest the pill.

Now explain that 30 min must pass before doing the second memory test and invite them to take part in another study about opinion research. To manipulate the dissonance level, tell those randomly assigned as high-choice: “I will leave it entirely up to you to decide if you would like to participate in it, but I would be very grateful if you would.” and as low choice: “During this wait, I am going to ask you to do a small task for this opinion research experiment.”

In both conditions, explain the task: “I would like you to write the strongest, the most forceful essay that you can taking the position that inflammatory speakers should be banned from college campuses.”. Emphasize for the high choice level participants: “Remember, you are under no obligation.”. Give them 10 min to complete the essay.

After they have finished writing, ask them to rate how they feel right now on a 31-point scale ranging from calm to tense. Next, ask them how they feel about adopting a ban against inflammatory speakers on campus on another 31-point scale, from strongly opposed to strongly in favor.

Additionally, to assess the effectiveness of the choice-level, ask the participants how free they felt to decline participation in this opinion research project, again on a 31-point scale, ranging from not free at all to extremely free.

Finally, debrief participants and reinforce that the pill was a placebo and thank them for taking part in the study.

To analyze the data, compute the average reported amount of tension for each of the conditions and plot the results. Use a 2 x 3 ANOVA to confirm the findings are significant.

Feelings were induced, as expected: Regardless of choice-level, participants in the arousal condition reported feeling more tense than controls, whereas those in the relaxation group reported much lower levels, consistent with being calm.

In contrast, the effects of choice-level were only evident within the control—no-information provided—condition. Here, high-choice participants reported feeling more tense than those in the low-choice condition, reinforcing that dissonance did have an impact, manipulating arousal.

To assess attitudinal differences in supporting the ban, average the ratings and use a 2 x 3 ANOVA to confirm the findings that in the no information condition, participants in the high-choice level showed larger attitude change by agreeing with the ban. These results suggest that dissonance was affecting their behavior.

This effect of dissonance was even greater for the relaxation condition with an exaggerated agreement to the ban in the high-choice level.

However, there was no effect of dissonance in the arousal condition; that is, the high-choice level showed similar support for the ban as the low-choice level, suggesting they ascribed their arousal to the external influence of the drug, thereby reducing their feelings of dissonance and change in attitude.

Now that you are familiar with misattribution of psychological arousal and how it can be used to alter the effects of cognitive dissonance, let’s look at other real-life situations where these principles can be applied.

Based on the research on misattribution of arousal, one might want to take a first date to perform an active sport in the hope that they will misinterpret their racing heart as a sign of attraction. This strategy is used all the time in popular romantic TV shows to help build attraction between contestants.

Research also suggests that in order for an individual to change their mind with respect to a given belief, psychological discomfort is necessary. For example, to convince someone to switch to a vegetarian diet, consider offering a psychologically arousing argument based on the ethics of animal welfare.

Cognitive dissonance is created the next time that person makes a choice between a meat meal and a vegetable one. If enough psychological discomfort exists, they will choose the vegetarian feast to lessen the dissonance.

Lastly, researchers have combined functional magnetic resonance imaging with dissonance manipulation to figure out what brain regions are involved. Participants were tasked with pretending that the unpleasant MRI experience was in fact pleasant.

The anterior cingulate cortex of those who were pretending showed increased activity as compared to controls, suggesting this region is involved in processes related to cognitive dissonance.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on the misattribution of arousal and cognitive dissonance. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design and execute an experiment with manipulations of psychological feelings and opinions, how to analyze and assess the results, as well as how to apply the principles to a number of real-world situations.

Thanks for watching!