激光显微切割RNA测序实验设计:从玉米叶片发展的经验分析

Summary

Many developmentally important genes have cell- or tissue-specific expression patterns. This paper describes LM RNA-seq experiments to identify genes that are differentially expressed at the maize leaf blade-sheath boundary and in lg1-R mutants compared to wild-type. The experimental considerations discussed here apply to transcriptomic analyses of other developmental phenomena.

Abstract

在发展重要作用的基因往往有空间和/或时间限制的表达模式。通常这些基因转录物不被检测或作为整个植物器官的转录分析差异表达(DE)不识别。激光显微切割RNA测序(RNA LM-SEQ)是一个强大的工具,以确定被取消的具体发展领域的基因。然而,蜂窝结构域的选择microdissect和比较,以及microdissections的精度是该实验的成功至关重要。在这里,两个例子说明了转录实验设计考虑;个LM的RNA-SEQ分析,以确定沿着玉米叶近端-远端轴DE基因,和第二个实验,以确定是-R liguleless1(LG1-R) 的 DE中的基因 突变体与野生型。 ,对这些实验的成功作出贡献的关键因素进行了详细的组织学和SI该区域的涂杂交分析待分析,在相当于发育阶段叶原基的选择,使用形态的地标选择区域用于显微切割,并精确测量畴的显微解剖。本文提供了通过LM RNA测序发育域分析详细的协议。此处呈现的数据说明了如何选择用于显微切割的区域会影响获得的结果。

Introduction

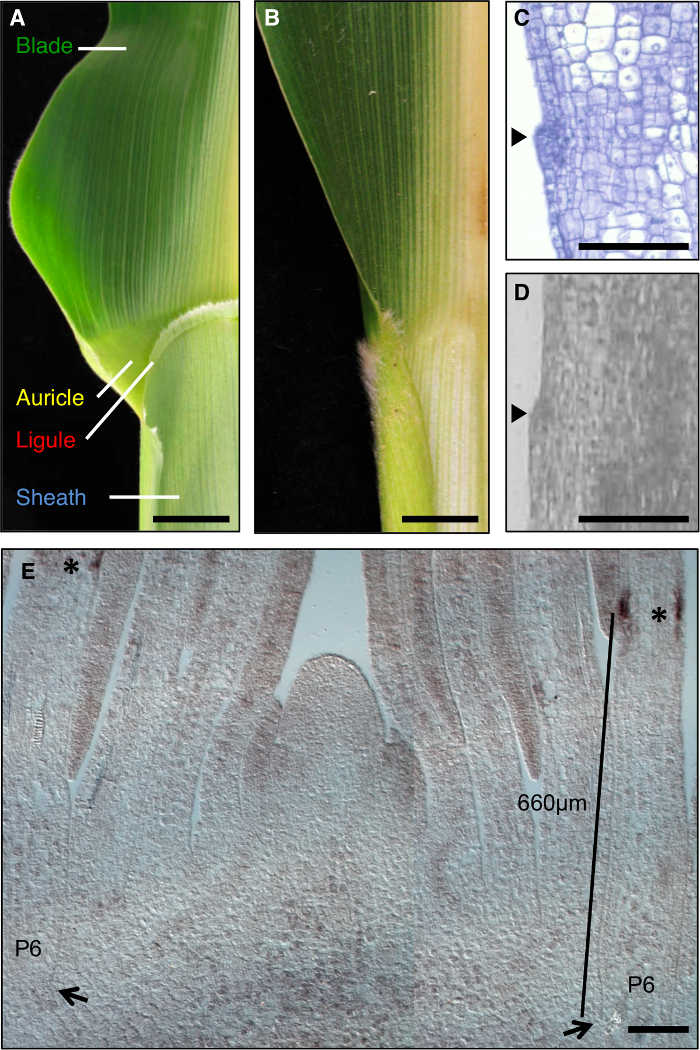

玉米叶是研究形态发生过程发展领域的形成一个理想的模型,因为它具有在刀片和鞘是服从遗传解剖( 图1A)之间有明显的边界。期间叶发育,较小的细胞的线性带的早期阶段,preligule带(PLB),细分叶原基成预刀片和预鞘域。刘海状叶舌和三角耳从PLB( 图1A,C,D)制定。遗传筛选已经确定了破坏刀片鞘边界突变。例如,隐性liguleless1(LG1)突变删除叶舌和耳廓1,2,3,4( 图1B)。 原位杂交透露,LG1成绩单积累的PLB和新兴叶舌,使其成为一个很好的标志物叶舌开发5,6( 图1E)。

图1:野生型和 liguleless1-R 玉米叶片。 (A)显示叶舌和耳廓的结构成熟的野生型叶刃鞘边界区域。 (B)成熟liguleless1-R叶表现没有叶舌和耳廓结构的叶片,鞘边界区域。在A和B的叶子已经被削减了一半沿中脉。 (C)通过纵野生型叶原基部分。样本已被处理和染色用于组织学分析。发起叶舌是从叶(箭头)的平面中突出的凸起显而易见。 (D)纵向教派通过野生型叶原基离子。如在文本中所描述的样品已被处理为LM。箭头指示发起叶舌。 (E) 在LG1茎尖外侧纵截面的原位杂交。星号表示在P6叶原基的PLB LG1成绩单积累。箭头指示P6原基的基地。律师表示从原基小巴的基本测量。在A和B比例尺= 20毫米。在CE比例尺= 100微米。这个数字已经从6参考(植物生物学家著作权协会)修改。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

在这项研究中,LM RNA测序是采用叶片鞘边界相对于所述叶原基和IDE其他部分在识别基因的套件,差异表达(DE) ntify基因是DE在LG1-R的突变体相对于野生型同胞。 LM RNA测序是在特定细胞或细胞结构域7定量转录物积累的方法。直线运动系统结合了激光器和用数码相机拍摄的显微镜。切片组织被固定在载玻片上,并通过显微镜观察。该软件LM通常包括绘图工具,允许用户在任何勾勒出选定的区域进行显微切割。激光切口沿着线,并且所选组织被弹射出滑动并进入悬挂在滑动上方的管中。 LM允许用户microdissect精确域,包括特定的细胞层和甚至单个细胞8,9。的RNA随后可以从显微组织中提取。随后,RNA测序组件利用下一代测序测序从提取的RNA 10产生cDNA文库,=“外部参照”> 11。

LM RNA测序的主要优点是能够量化精确定义的域成绩单的积累能力,来分析整个转录同时7的能力。该技术特别适合于探测早期发育事件,其中所述感兴趣区域是经常微观。先前的研究已利用的LM与微阵列技术相结合,研究在植物9,12,13的发育过程。 RNA测序具有在宽的动态范围,包括低表达基因定量转录物的优点,和现有序列信息不要求10,11。此外,LM RNA-SEQ有突出由于遗传冗余或到的杀伤力损失OF-可以在诱变筛选错过发育的重要基因的潜力功能突变体。

发育重要的基因,如窄护套1(NS1)和杯形cotyledon2(CUC2),通常具有的只是一个具体的表达模式或几个电池单元17,18,19,20。许多仅在早期发育阶段,而不是在成熟器官中表达。当整个器官或大结构域进行了分析,这些细胞特异性转录物稀释并可能无法在更常规的分析进行检测。通过允许精确限定域的分析,LM RNA测序使得这些组织特异性基因被识别和量化。

在这里描述的实验中的成功的关键因素是一个彻底的组织学分析是指导用于分析的合适的发育阶段和域的选择,以及精确measureme对于LM细胞组织域的NT。以确保等效域进行采样的所有重复,组织是从叶原基在相同发育阶段收集和显微结构域诸如新兴叶舌( 图2),测定相对于形态的地标。已知的是某些基因在从尖端到叶的基部的梯度表示。通过测量精确域的变化,由于从沿叶近端-远端轴线的不同位置取样保持为最小( 图3A)。由microdissecting大小相同的域,由于变异差分细胞特异性转录物的稀释也减少( 图3B)。茎尖的外侧纵切片用于所有microdissections。这些是垂直于脉利润率轴线( 图4)的部分。只使用部分包含了SAM确保能等效侧向地区叶原基进行了分析。

在处理和切片用于LM样品,叶舌向外生长的第一形态迹象是在近轴侧的凸点由于在近轴表皮( 图1D, 图2)平周细胞分裂。它被确定新兴叶舌可以在plastochron 7阶段叶原基可靠地识别。我们感兴趣的整个叶舌区域表达的基因,包括新兴叶舌并将细胞立即远侧将形成耳廓。为了确保等效组织的选择进行了改造,所述叶舌凸点被用作形态学里程碑,被选定为LM( 图2A,2B)中心的叶舌凸点100微米的矩形。从同一叶原基被预先选定的叶片和预鞘的等效尺寸矩形。

liguleless突变体的分析提出了不同的challeNGE; LG1-R突变体不形成舌,因此该形态特征不能被用于选择该区域的LM。相反,在野生型叶原基LG1转录积累的域被确定,并且被定义,将包含此结构域的区域。作为被用于最终分析这些初步分析在幼苗从同一种植进行的,因为以前的工作已经表明,PLB的位置取决于生长条件。 原位杂交表明LG1转录本P6的PLB的叶原基( 图1E)累积。我们选择了一个域400-900微米从涵盖LG1表达式的域(紫色长方形, 图2A)和捕获野生型和LG1-R的植物,这些等效区域的叶原基的基础。为了比较转录时尽量减少遗传背景和生长条件的变化在LG1-R和野生型植物,分离的突变体和野生型同胞家属牛逼积累量使用。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

实验设计是在RNA-SEQ实验的关键因素。主要问题是精确域和发育阶段(多个)进行分析,和什么比较将进行。这是认为在比较而言是至关重要的,因为输出是通常被两个或多个条件之间DE基因的列表。如同所有的实验中,在一个时间,以改变只有一个变量是重要的。例如,比较不同的叶域时,叶片的相同年龄和发育阶段,在同样的条件下生长,应比较。

这些实验的目的是,以?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

作者感谢S.哈克对正在进行的合作,推动就叶舌发展的讨论。这项工作是由美国国家科学基金会资助MCB 1052051和IOS-1848478的支持。

Materials

| Diethyl pyrocarbonate | Sigma-Aldrich | 159220 | Used for RNase treatment of solutions |

| Razor blades | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 72000 | |

| RNase Zap | Sigma-Aldrich | R2020-250ML | RNase decontamination solution |

| Ethanol absolute 200 proof | Fisher Scientific | BP28184 | |

| Acetic acid, glacial | Sigma-Aldrich | A6283 | |

| Glass vials – 22mL | VWR | 470206-384 | |

| Xylenes, histological grade | Sigma-Aldrich | 534056-4L | |

| Paraplast plus | Sigma-Aldrich | P3683-1KG | |

| Disposable base molds, 15 x 15 x 5mm | VWR | 15154-072 | |

| Embedding rings | VWR | 15154-303 | |

| Silica gel packets | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 71206-01 | Desiccant for storage of paraffin blocks |

| Oven | Fisher Scientific | 15-103-0503 | Oven must maintain temperature of 60° C |

| Paraffin embedding station | Leica | EG1160 | |

| Microtome | Leica | RM2235 | |

| Slide warmer | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 71317-10 | |

| Coplin jars | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 70316-02 | |

| Laser microdissector | Zeiss | ||

| KIMWIPES™ Delicate Task Wipers | Kimberly-Clark Professional | 34120 | Lint-free wipes for wicking excess solutions from microscope slides |

| Membrane Slide 1.0 PEN | Zeiss | 415190-9041-000 | Slides for laser microdissection |

| Adhesive Cap 200 opaque | Zeiss | 415190-9181-000 | Tubes for laser microdissection |

| PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | KIT0204 |

References

- Becraft, P. W., Bongard-Pierce, D. K., Sylvester, A. W., Poethig, R. S., Freeling, M. The liguleless-1 gene acts tissue specifically in maize leaf development. Dev Biol. 141 (1), 220-232 (1990).

- Sylvester, A. W., Cande, W. Z., Freeling, M. Division and differentiation during normal and liguleless-1 maize leaf development. Development. 110 (3), 985-1000 (1990).

- Moreno, M. A., Harper, L. C., Krueger, R. W., Dellaporta, S. L., Freeling, M. liguleless1 encodes a nuclear-localized protein required for induction of ligules and auricles during maize leaf organogenesis. Genes Dev. 11 (5), 616-628 (1997).

- Emerson, R. A. The inheritance of the ligule and auricle of corn leaves. Neb. Agr. Exp. Sta. An. Rep. 25, 81-85 (1912).

- Moon, J., Candela, H., Hake, S. The Liguleless narrow mutation affects proximal-distal signaling and leaf growth. Development. 140 (2), 405-412 (2013).

- Johnston, R., et al. Transcriptomic Analyses Indicate That Maize Ligule Development Recapitulates Gene Expression Patterns That Occur during Lateral Organ Initiation. Plant Cell. 26 (12), 4718-4732 (2014).

- Schmid, M. W., et al. A powerful method for transcriptional profiling of specific cell types in eukaryotes: laser-assisted microdissection and RNA sequencing. PLoS One. 7 (1), e29685 (2012).

- Kerk, N. M., Ceserani, T., Tausta, S. L., Sussex, I. M., Nelson, T. M. Laser capture microdissection of cells from plant tissues. Plant Physiol. 132 (1), 27-35 (2003).

- Nakazono, M., Qiu, F., Borsuk, L. A., Schnable, P. S. Laser-capture microdissection, a tool for the global analysis of gene expression in specific plant cell types: identification of genes expressed differentially in epidermal cells or vascular tissues of maize. Plant Cell. 15 (3), 583-596 (2003).

- Marioni, J. C., Mason, C. E., Mane, S. M., Stephens, M., Gilad, Y. RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Res. 18 (9), 1509-1517 (2008).

- Wang, Z., Gerstein, M., Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 10 (1), 57-63 (2009).

- Brooks, L., et al. Microdissection of shoot meristem functional domains. PLoS Genet. 5 (5), e1000476 (2009).

- Cai, S., Lashbrook, C. C. Stamen abscission zone transcriptome profiling reveals new candidates for abscission control: enhanced retention of floral organs in transgenic plants overexpressing Arabidopsis ZINC FINGER PROTEIN2. Plant Physiol. 146 (3), 1305-1321 (2008).

- Li, P., et al. The developmental dynamics of the maize leaf transcriptome. Nat Genet. 42 (12), 1060-1067 (2010).

- Eveland, A. L., et al. Regulatory modules controlling maize inflorescence architecture. Genome Res. 24 (3), 431-443 (2014).

- Takacs, E. M., et al. Ontogeny of the maize shoot apical meristem. Plant Cell. 24 (8), 3219-3234 (2012).

- Aida, M., Ishida, T., Tasaka, M. Shoot apical meristem and cotyledon formation during Arabidopsis embryogenesis: interaction among the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS genes. Development. 126 (8), 1563-1570 (1999).

- Ishida, T., Aida, M., Takada, S., Tasaka, M. Involvement of CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes in gynoecium and ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 41 (1), 60-67 (2000).

- Takada, S., Hibara, K., Ishida, T., Tasaka, M. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 gene of Arabidopsis regulates shoot apical meristem formation. Development. 128 (7), 1127-1135 (2001).

- Nardmann, J., Ji, J., Werr, W., Scanlon, M. J. The maize duplicate genes narrow sheath1 and narrow sheath2 encode a conserved homeobox gene function in a lateral domain of shoot apical meristems. Development. 131 (12), 2827-2839 (2004).

- Bonner, W. A., Hulett, H. R., Sweet, R. G., Herzenberg, L. A. Fluorescence activated cell sorting. Rev Sci Instrum. 43 (3), 404-409 (1972).

- Birnbaum, K., et al. A gene expression map of the Arabidopsis root. Science. 302 (5652), 1956-1960 (2003).

- Brady, S. M., et al. A high-resolution root spatiotemporal map reveals dominant expression patterns. Science. 318 (5851), 801-806 (2007).

- Carter, A. D., Bonyadi, R., Gifford, M. L. The use of fluorescence-activated cell sorting in studying plant development and environmental responses. Int J Dev Biol. 57 (6-8), 545-552 (2013).

- Ruzin, S. E. . Plant microtechnique and microscopy. , (1999).

- Jackson, D., Veit, B., Hake, S. Expression of maize KNOTTED1 related homeobox genes in the shoot apical meristem predicts patterns of morphogenesis in the vegetative shoot. Development. 120, 405-413 (1994).

- Javelle, M., Marco, C. F., Timmermans, M. In situ hybridization for the precise localization of transcripts in plants. J Vis Exp. (57), e3328 (2011).

- Day, R. C., McNoe, L., Macknight, R. C. Evaluation of global RNA amplification and its use for high-throughput transcript analysis of laser-microdissected endosperm. Int J Plant Genomics. , 61028 (2007).