간단한 교반 용기를 사용하여 알긴산 염 비즈에서 포유류 세포 캡슐화

Summary

이 동영상과 원고는 단순 교반 용기를 사용하여 큰 배치로 생산할 수있는 0.5 % ~ 10 % 알긴산 염 비즈로 포유류 세포를 캡슐화하는 유제 기반 방법을 설명합니다. 캡슐화 된 세포는 시험 관내에서 배양 되거나 세포 치료 응용을 위해 이식 될 수 있습니다.

Abstract

알기 네이트 비드에서의 세포 캡슐화는 시험 관내 뿐만 아니라 생체 내 면역 분리 를 위해 고정화 된 세포 배양 에 사용되어왔다. 췌도 소포 캡슐화는 동종 또는 이종 이식에서 랑게르한 생존을 증가시키는 수단으로서 광범위하게 연구되어왔다. 알지네이트 캡슐화는 일반적으로 노즐 압출 및 외부 겔화에 의해 달성됩니다. 이 방법을 사용하여, 노즐의 끝에 형성된 세포 함유 알지네이트 물방울은 물방울로 확산 될 때 이온 성 알지네이트 겔화를 유발하는 2가 양이온을 함유하는 용액에 빠지게된다. 노즐 팁에서의 액적 생성에 대한 요구는 용적 처리량 및 달성 될 수있는 알긴산 염 농도를 제한한다. 이 비디오는 포유류 세포를 70 % ~ 90 %의 세포 생존율을 갖는 0.5 %에서 10 %의 알지네이트로 캡슐화하는 확장 가능한 유화 방법을 설명합니다. 이 대체 방법에 의해, 세포 및 탄산 칼슘을 함유하는 알긴산 방울을 미네랄 오일,내부 칼슘 방출 및 이온 성 알기 네이트 겔화를 유도하는 pH의 감소로 낮아진다. 현재 방법은 유화 20 분 이내에 알지네이트 구슬의 생산을 허용합니다. 캡슐화 단계에 필요한 장비는 대부분의 실험실에서 사용할 수있는 단순 교반 용기로 구성됩니다.

Introduction

포유류 세포 캡슐화는 면역 거부 반응으로부터 이식 된 세포를 보호하거나 고정화 된 세포 배양을위한 3 차원 지지체를 제공하는 수단으로 광범위하게 연구되어왔다 2 , 3 , 4 . 알지네이트 구슬의 췌장 섬모 캡슐화는 동종 제 5 , 6 또는 이종 동물 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 개의 설치류에서 당뇨병을 역전시키는 데 사용되었습니다. 제 1 형 당뇨병을 치료하기위한 캡슐화 된 췌도 이식의 전임상 시험과 임상 시험이 진행 중이다 ( 13 , 14 , 15) . 이식 용도 또는보다 큰 규모의 경우체외 고정화 세포 생산, 노즐 기반 비드 발생기가 일반적으로 사용됩니다. 전형적으로, 알지네이트와 세포의 혼합물은 노즐을 통해 펌핑되어 2가 양이온을 함유하는 진탕 된 용액에 떨어지는 액 적이 형성되어 액적의 외부 겔화를 일으킨다. 동축 가스 흐름 ( 16 , 17) , 노즐 진동 ( 18) , 정전 반발력 ( 19) 또는 회전 와이어 ( 20) 는 노즐 팁에서 액적 형성을 용이하게한다.

기존의 비드 발생기의 주요 단점은 제한된 처리량과 적절한 비드 형성을 가져 오는 용액 점도 범위가 제한된다는 것입니다. 높은 유속에서, 노즐을 빠져 나가는 유체는 노즐 직경보다 작은 방울로 분열되어 크기 조절을 감소시킵니다. 다중 노즐 비드 발생기를 사용하여 처리량을 늘릴 수 있지만노즐 사이의 균일 한 유량 분포와 용액의 사용> 0.2 Pas는 문제가있다. 마지막으로 모든 노즐 기반 장치는 사용되는 노즐의 직경이 100 μm와 500 μm 사이 인 반면 섬의 ~ 15 %는 200 μm보다 클 수 있기 때문에 섬에 약간의 손상을 줄 것으로 예상됩니다 23 .

이 비디오에서는 드롭 다운 드롭 대신 단일 유화 단계에서 드롭 릿을 형성하여 포유류 세포를 캡슐화하는 대체 방법에 대해 설명합니다. 비드 생산이 간단한 교반 용기에서 수행되기 때문에,이 방법은 장비 비용이 저렴한 (~ 1 mL)에서 대규모 (10 3 L 범위) 비드 생산에 적합합니다. 이 방법은 비드 생성 시간이 짧은 ( 예 : 20 분) 넓은 알긴산 점도를 사용하여 구형도가 높은 비드를 생산할 수 있습니다. 이 방법은 원래 Poncelet et al에 의해 개발되었다 .엘. 25 , 26 및 DNA 27 , 인슐린 29 및 박테리아 30을 포함한 단백질 28 을 고정시키는 데 사용되었습니다. 우리는 최근에 췌장 베타 세포주 31 , 32 및 일차 췌장 조직 32를 사용하여 포유 동물 세포의 캡슐화에 이러한 방법을 적용했습니다.

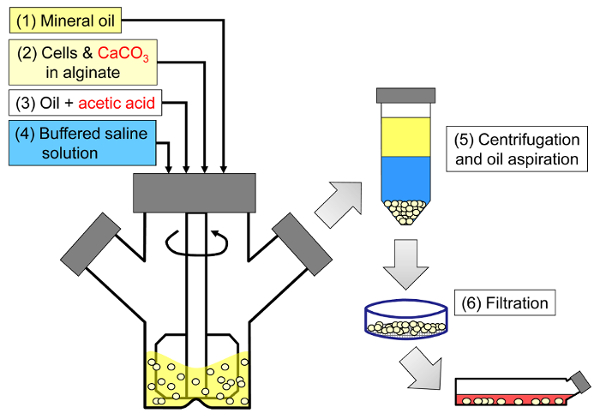

이 방법의 원리는 미네랄 오일에 알지네이트 방울로 구성된 유 중수 에멀젼을 생성 한 다음 알긴산 방울을 내부 겔화시키는 것입니다 ( 그림 1 ). 먼저, 봉입 제 ( 예 : 세포)는 초기 공정 pH에서 낮은 용해도를 갖는 미세 입자 칼슘 염을 함유하는 알긴산 염 용액에 분산된다. 이어서 알긴산 염 혼합물을 교반 된 유기상에 첨가하여 보통 에멀젼의 존재하에 에멀젼을 생성시킨다.계면 활성제. 포유 동물 세포 캡슐화의 경우, 혈청에 존재하는 성분은 계면 활성제로 작용할 수 있습니다. 다음으로, 수성 상으로 분할되는 유용성 산을 첨가함으로써 칼슘 염을 가용화시키기 위해 pH를 감소시킨다. 미네랄 오일 / 물 분배 계수가 <0.005 33 인 초산은 오일에 미리 용해시킨 다음에 유상에 첨가하여 유상에 혼합하고 신속하게 수성 상에 분배한다. 그림 2 는 산성화 및 내부 겔화 단계에서 일어나는 화학 반응과 확산을 보여줍니다. 마지막으로, 캡슐화 된 세포는 상 전이, 원심 분리에 의한 상분리 촉진, 반복 된 세척 단계 및 여과에 의해 회수된다. 이러한 단계는 품질 관리 분석, 시험 관내 세포 배양 및 / 또는 캡슐화 된 세포의 이식을위한 비드 및 세포 샘플링에 의해 수행 될 수있다.

<p class = "jove_content"fo : keep-together.within-page = "1">

그림 1 : 포유 동물 세포를 캡슐화하는 유화 기반 공정의 개략도. 구슬은 처음에 알긴산 염, 세포 및 CaCO3 혼합물을 미네랄 오일 (도식의 1 단계와 2 단계)에 유화시켜 아세트산을 첨가하여 내부 겔화를 유발함으로써 생성됩니다 (3 단계). 이어서, 겔화 된 비드를 수성 완충액을 첨가하여 위상 반전 (단계 4), 원심 분리 및 오일 흡인 (단계 5), 및 여과 (단계 6)를 수행함으로써 오일로부터 분리 하였다. 마지막으로, 필터 상에 수집 된 비드 는 시험 관내 배양 또는 이식을 위해 세포 배양 배지로 옮겨진다. 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

<imgalt = "그림 2"class = "xfigimg"src = "/ files / ftp_upload / 55280 / 55280fig2.jpg"/>

그림 2 : 내부 겔화 동안 일어나는 반응 및 확산 단계. (1) 아세트산은 유기상에 첨가되고 대류에 의해 알지네이트 방울로 수송된다. (2) 아세트산은 수상으로 분리된다. (3) 물의 존재 하에서, 산은 해리하고 확산되어 진한 파란색으로 묘사 된 CaCO3 입자에 이른다. (4) H + 이온은 CaCO3에서 Ca2 + 이온과 교환되어 Ca2 + 이온을 방출한다. (5) 칼슘 이온은 미 반응 알지네이트를 만나 알지네이트 사슬의 이온 결합 가교 결합을 일으킬 때까지 확산한다. 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

종래의 노즐 기반의 세포 캡슐과는 달리, 넓은 비드 크기 분포가 얻어진다이는 교반 된 유화에서 액적 형성의 메카니즘으로 인해이 공정으로부터 유래된다. 일부 응용 프로그램의 경우이 구슬 크기 분포가 문제가 될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 더 큰 조각의 세포가 작은 비드의 비드 표면에 노출 될 수 있습니다. 영양소 ( 예 : 산소)의 제한이 우려된다면 큰 구슬에서는 이러한 한계가 악화 될 수 있습니다. 교반 된 유화 방법의 장점은 평균 비드 크기가 유화 단계 동안 교반 속도를 변화시킴으로써 쉽게 조절 될 수 있다는 것이다. 광범위한 비드 크기 분포는 또한 캡슐화 된 셀 성능에 대한 비드 크기의 효과를 연구하기 위해 이용 될 수 있습니다.

유화 및 내부 겔화에 의한 포유류 세포 캡슐화는 비드 발생기가 장착되지 않은 실험실에 대한 흥미로운 대안입니다. 또한,이 방법은 사용자에게 처리 시간을 줄이거 나 매우 낮은 또는 매우 높은 알긴산 염 농도에서 비드를 생성하는 옵션을 제공합니다ations.

아래에 약술 된 프로토콜은 10mM 4- (2- 하이드 록시 에틸) -1- 피페 라진 에탄 술폰산 (HEPES) 완충액에서 제조 된 5 % 알긴산 염 용액 10.5mL에 세포를 캡슐화하는 방법을 기술한다. 알지네이트는 이식 등급 LVM (낮은 점도의 높은 만 뉴론 산 함량)과 MVG (중간 점도의 높은 guluronic acid 함량) 알지네이트의 50:50 혼합물로 구성됩니다. 최종 농도 24 mM의 탄산 칼슘이 물리적 가교제로 사용됩니다. 경질 미네랄 오일은 유기상을 구성하고 아세트산은 유제를 산성화하고 내부 겔화를 유발하는 데 사용됩니다. 그러나, 알지네이트 유형 및 조성뿐만 아니라 선택된 공정 완충액은 원하는 적용 32 에 의존한다. 다양한 알지네이트 유형 (물질 표 참조)이이 프로토콜을 사용하여 비즈를 생산하는 데 사용되었습니다.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

내부 겔화 반응 동안 다양한 단계 ( 그림 2 )가 전체 반응 속도를 제한 할 수 있습니다. ~ 2.5 μm보다 큰 탄산 칼슘 입자의 경우, 탄산염 용해 속도는 속도 제한 26 , 44 로 나타났습니다. 내부 칼슘 방출을 유도하는 산성화 단계는 또한 세포 생존에 영향을 미치는 중요한 공정 변수로도 나타났습니다 32 . 따라서 내부 겔화를 유?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

유화 공정에 대한 그녀의 토양 개발에 대한 질 오스본 (Jill Osborne)과 기술 지원에 대한 로렌 윌킨슨 (Lauren Wilkinson)에게 감사드립니다. Igor Laçik, Timothy J. Kieffer 박사 및 James D. Johnson 선생님의 의견과 협조에 감사드립니다. Diabète Québec, JDRF, ThéCell, 센터 연구 센터 (CQMF), 자연 과학 및 공학 연구위원회 (NSERC), 인간 섬 이식 및 베타 세포 재생 센터, 캐나다 줄기 세포 네트워크, 마이클 스미스 보건 연구 재단, 자금 지원에 대한 비용 및 비용 865

Materials

| Reagents and consumables | |||

| LVM alginate (transplantation-grade) | Novamatrix | Non-applicable | Referred to as "alginate #1" in the results. |

| MVG alginate (transplantation-grade) | Novamatrix | Non-applicable | Referred to as "alginate #2" in the results. |

| Alginate (cell culture-grade) | Sigma | A0682 (low viscosity) or A2033 (medium viscosity) | A2033 is referred to as "alginate #3" in the results. |

| DMEM | Life Technologies | 11995-065 | |

| Fetal bovine serum, characterized, Canadian origin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | SH3039603 | |

| Glutamine | Life Technologies | 25030 | |

| Penicillin and streptomycin | Sigma | P4333-100ML | |

| HEPES, cell culture tested | Sigma | H4034-100G | |

| NaCl | Thermo Fisher Scientific | S271-1 | |

| Fine-grain CaCO3 | Avantor Materials | 1301-01 | After preparing the CaCO3 suspension, sonicate and use within one month. |

| Light mineral oil | Thermo Fisher Scientific | O121-4 | Sterile filter through a 0.22 μm pore size membrane prior to use. |

| Glacial acetic acid | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A38-500 | Handle with caution: refer to MSDS. |

| Sterile spatulas | Sigma | CLS3004-100EA | |

| Sterile nylon cell strainers, 40 µm | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 08-771-1 | |

| Serological pipettes (2 mL, 5 mL, 10 mL, 25 mL) | Sarstedt | 86.1252.001, 86.1253.001, 86.1254.001 and 86.1685.001 | |

| Pasteur pipettes | VWR | 14673-043 | |

| Toluidine Blue-O | Sigma | T3260 | |

| Equipment | |||

| 100 mL microcarrier spinner flasks | Bellco | 1965-00100 | The impeller configuration with recent models may not be suitable for adequate emulsification. A blade able to sweep the oil down to 0.5 cm from the bottom of the flask can be custom-made from a Teflon sheet. |

| Magnetic stir plate with adjustable speed | Bellco | 7760-06005 | The rotation speed should be calibrated (e.g. using a tachometer) prior to use. |

| Cell counter | Innovatis | Cedex AS20 | This system is now sold by Roche. This automated cell counter can also be replaced by manual cell enumeration after Trypan blue staining using a hemocytometer. |

| LED light box | Artograph | LightPad® PRO | This item can be replaced by other types of illuminators. |

| Handheld camera | Canon | PowerShot A590 IS | A variety of handheld cameras can be used to capture toluidine blue-o stained bead images. A ruler should be placed next to the Petri dish containing the beads prior to acquiring images. |

| Fluorescence microscope with phase contrast and adequate fluorescence filters | Olympus | IX81 | Several microscopy systems were used to image the beads. The results shown here were obtained with an IX81 microscope equipped with GFP and TRITC fluorescence filters. To capture entire beads, 4X to 20X objectives were used depending on the agitation rate. Live/dead staining images were typically captured with 20X to 40X objectives. |

| Image aquisition software | Molecular Devices | Metamorph | A variety of image acquisition software can be used to acquire phase contrast and fluorescence images. |

| Image analysis freeware | CellProfiler | Non-applicable | A variety of image analysis software can be used to identify beads as objects and analyze bead size (e.g. ImageJ). |

References

- Scharp, D. W., Marchetti, P. Encapsulated islets for diabetes therapy: history, current progress, and critical issues requiring solution. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 67-68, 35-73 (2014).

- Chayosumrit, M., Tuch, B., Sidhu, K. Alginate microcapsule for propagation and directed differentiation of hESCs to definitive endoderm. Biomaterials. 31 (3), 505-514 (2010).

- Sidhu, K., Kim, J., Chayosumrit, M., Dean, S., Sachdev, P. Alginate microcapsule as a 3D platform for propagation and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESC) to different lineages. J Vis Exp. (61), (2012).

- Tostoes, R. M., et al. Perfusion of 3D encapsulated hepatocytes–a synergistic effect enhancing long-term functionality in bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 108 (1), 41-49 (2011).

- Duvivier-Kali, V. F., Omer, A., Parent, R. J., O’Neil, J. J., Weir, G. C. Complete protection of islets against allorejection and autoimmunity by a simple barium-alginate membrane. Diabetes. 50 (8), 1698-1705 (2001).

- Omer, A., et al. Long-term normoglycemia in rats receiving transplants with encapsulated islets. Transplantation. 79 (1), 52-58 (2005).

- Rayat, G. R., Rajotte, R. V., Ao, Z., Korbutt, G. S. Microencapsulation of neonatal porcine islets: protection from human antibody/complement-mediated cytolysis in vitro and long-term reversal of diabetes in nude mice. Transplantation. 69 (6), 1084-1090 (2000).

- Korbutt, G. S., Mallett, A. G., Ao, Z., Flashner, M., Rajotte, R. V. Improved survival of microencapsulated islets during in vitro culture and enhanced metabolic function following transplantation. Diabetologia. 47 (10), 1810-1818 (2004).

- Luca, G., et al. Improved function of rat islets upon co-microencapsulation with Sertoli’s cells in alginate/poly-L-ornithine. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2 (3), E15 (2001).

- Omer, A., et al. Survival and maturation of microencapsulated porcine neonatal pancreatic cell clusters transplanted into immunocompetent diabetic mice. Diabetes. 52 (1), 69-75 (2003).

- Schneider, S., et al. Long-term graft function of adult rat and human islets encapsulated in novel alginate-based microcapsules after transplantation in immunocompetent diabetic mice. Diabetes. 54 (3), 687-693 (2005).

- Cui, H., et al. Long-term metabolic control of autoimmune diabetes in spontaneously diabetic nonobese diabetic mice by nonvascularized microencapsulated adult porcine islets. Transplantation. 88 (2), 160-169 (2009).

- Krishnan, R., Alexander, M., Robles, L., Foster, C. E., Lakey, J. R. Islet and stem cell encapsulation for clinical transplantation. Rev Diabet Stud. 11 (1), 84-101 (2014).

- Robles, L., Storrs, R., Lamb, M., Alexander, M., Lakey, J. R. Current status of islet encapsulation. Cell Transplant. 23 (11), 1321-1348 (2014).

- Desai, T., Shea, L. D. Advances in islet encapsulation technologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. , (2016).

- Anilkumar, A. V., Lacik, I., Wang, T. G. A novel reactor for making uniform capsules. Biotechnol Bioeng. 75 (5), 581-589 (2001).

- Wolters, G. H., Fritschy, W. M., Gerrits, D., van Schilfgaarde, R. A versatile alginate droplet generator applicable for microencapsulation of pancreatic islets. J Appl Biomater. 3 (4), 281-286 (1991).

- Heinzen, C., Marison, I., Berger, A., von Stockar, U. Use of vibration technology for jet break-up for encapsulation of cells, microbes and liquids in monodisperse microcapsules. Practical Aspects of Encapsulation Technologies. , 19-25 (2002).

- Poncelet, D., et al. A Parallel plate electrostatic droplet generator: Parameters affecting microbead size. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 42 (2-3), 251-255 (1994).

- Prüße, U., Dalluhn, J., Breford, J., Vorlop, K. D. Production of Spherical Beads by JetCutting. Chemical Engineering & Technology. 23 (12), 1105-1110 (2000).

- Hoesli, C. A. . Bioprocess development for the cell-based treatment of diabetes (PhD thesis). , (2010).

- Brandenberger, H., Widmer, F. A new multinozzle encapsulation/immobilisation system to produce uniform beads of alginate. J Biotechnol. 63 (1), 73-80 (1998).

- Merani, S., Toso, C., Emamaullee, J., Shapiro, A. M. Optimal implantation site for pancreatic islet transplantation. Br J Surg. 95 (12), 1449-1461 (2008).

- Reis, C. P., Neufeld, R. J., Vilela, S., Ribeiro, A. J., Veiga, F. Review and current status of emulsion/dispersion technology using an internal gelation process for the design of alginate particles. J Microencapsul. 23 (3), 245-257 (2006).

- Poncelet, D., et al. Production of alginate beads by emulsification/internal gelation. I. Methodology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 38 (1), 39-45 (1992).

- Poncelet, D., et al. Production of alginate beads by emulsification/internal gelation. II. Physicochemistry. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 43 (4), 644-650 (1995).

- Alexakis, T., et al. Microencapsulation of DNA within alginate microspheres and crosslinked chitosan membranes for in vivo application. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 50 (1), 93-106 (1995).

- Vandenberg, G. W., De La Noue, J. Evaluation of protein release from chitosan-alginate microcapsules produced using external or internal gelation. J Microencapsul. 18 (4), 433-441 (2001).

- Silva, C. M., Ribeiro, A. J., Figueiredo, I. V., Goncalves, A. R., Veiga, F. Alginate microspheres prepared by internal gelation: development and effect on insulin stability. Int J Pharm. 311 (1-2), 1-10 (2006).

- Larisch, B. C., Poncelet, D., Champagne, C. P., Neufeld, R. J. Microencapsulation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. J Microencapsul. 11 (2), 189-195 (1994).

- Hoesli, C. A., et al. Reversal of diabetes by betaTC3 cells encapsulated in alginate beads generated by emulsion and internal gelation. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 100 (4), 1017-1028 (2012).

- Hoesli, C. A., et al. Pancreatic cell immobilization in alginate beads produced by emulsion and internal gelation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 108 (2), 424-434 (2011).

- Reinsel, M. A., Borkowski, J. J., Sears, J. T. Partition Coefficients for Acetic, Propionic, and Butyric Acids in a Crude Oil/Water System. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 39 (3), 513-516 (1994).

- Xiu-Dong, L., Wei-Ting, Y., Jun-Zhang, L., Xiao-Jun, M., Quan, Y. Diffusion of acetic acid across oil/water interface in emulsification-internal gelation process for preparation of alginate gel beads. Chemical Research in Chinese Universities. 23 (5), 579-584 (2007).

- Fernandez, S. A., et al. Emulsion-based islet encapsulation: predicting and overcoming islet hypoxia. Bioencapsulation Innovations. (220), 14-15 (2014).

- Carpenter, A. E., et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7 (10), R100 (2006).

- Hinze, J. O. Fundamentals of the hydrodynamic mechanism of splitting in dispersion processes. AIChE Journal. 1 (3), 289-295 (1955).

- Kolmogorov, A. N. On the breakage of drops in a turbulent flow (translated from Russian). Doklady Akademii Nauk. 66, 825-828 (1949).

- Davies, J. T. Drop Sizes of Emulsions Related to Turbulent Energy-Dissipation Rates. Chemical Engineering Science. 40 (5), 839-842 (1985).

- Pacek, A. W., Chamsart, S., Nienow, A. W., Bakker, A. The influence of impeller type on mean drop size and drop size distribution in an agitated vessel. Chemical Engineering Science. 54 (19), 4211-4222 (1999).

- Steiner, H., et al. Numerical simulation and experimental study of emulsification in a narrow-gap homogenizer. Chemical Engineering Science. 61 (17), 5841-5855 (2006).

- Tcholakova, S., Denkov, N. D., Lips, A. Comparison of solid particles, globular proteins and surfactants as emulsifiers. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 10 (12), 1608-1627 (2008).

- Lagisetty, J. S., Das, P. K., Kumar, R., Gandhi, K. S. Breakage of viscous and non-Newtonian drops in stirred dispersions. Chemical Engineering Science. 41 (1), 65-72 (1986).

- Draget, K. I., Ostgaard, K., Smidsrod, O. Homogeneous Alginate Gels – a Technical Approach. Carbohydrate Polymers. 14 (2), 159-178 (1990).

- Poncelet, D., Dulieu, C., Jacquot, M., Wijffels, R. H. . Immobilized Cells. , 15-30 (2001).

- Islam, A. W., Zavvadi, A., Kabadi, V. N. Analysis of Partition Coefficients of Ternary Liquid-Liquid Equilibrium Systems and Finding Consistency Using Uniquac Model. Chemical and Process Engineering-Inzynieria Chemiczna I Procesowa. 33 (2), 243-253 (2012).

- Quong, D., Neufeld, R. J., Skjak-Braek, G., Poncelet, D. External versus internal source of calcium during the gelation of alginate beads for DNA encapsulation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 57 (4), 438-446 (1998).

- De Vos, P., De Haan, B. J., Van Schilfgaarde, R. Upscaling the production of microencapsulated pancreatic islets. Biomaterials. 18 (16), 1085-1090 (1997).

- Gross, J. D., Constantinidis, I., Sambanis, A. Modeling of encapsulated cell systems. J Theor Biol. 244 (3), 500-510 (2007).