走行関連研究のための触覚振動ツールキットとドライビングシミュレーションプラットフォーム

Summary

このプロトコルは、運転シミュレーションプラットフォームと、運転関連研究の調査のための触覚振動ツールキットを記述します。触覚警告の有効性を探る模範的な実験も提示される。

Abstract

衝突警報システムは、気晴らしや眠気運転の防止に重要な役割を果たしています。これまでの研究では、ドライバーのブレーキ応答時間を短縮する際の触覚警告の利点が実証されています。同時に、触覚警告は、部分的に自律走行車の引き継ぎ要求(TOR)に有効であることが証明されています。

触覚警告の性能を最適化する方法は、この分野で進行中のホットな研究トピックです。このように、提示された低コストの運転シミュレーションソフトウェアと方法は、調査に参加するより多くの研究者を引き付けるために導入されています。提示されたプロトコルは、5つのセクションに分かれています:1)参加者、2)運転シミュレーションソフトウェア構成、3)ドライビングシミュレータ調製、4)振動ツールキットの構成と準備、および5)実験を行う。

例示的な研究では、参加者は触覚振動ツールキットを着用し、カスタマイズされたドライビングシミュレーションソフトウェアを使用して確立された車に続くタスクを実行しました。フロント車両は断続的にブレーキをかけ、前部車両がブレーキをかけるたびに振動警告が発令されました。参加者は、前部車両の突然のブレーキにできるだけ早く対応するように指示されました。ブレーキの応答時間やブレーキ応答率などの駆動ダイナミクスを、データ解析用のシミュレーションソフトウェアによって記録した。

提示されたプロトコルは異なったボディの位置の蝕知の警告の有効性についての洞察を提供する。このプロトコルは、例示実験で実証されている自動車フォロータスクに加えて、コード開発なしで簡単なソフトウェア構成を行うことで、他のパラダイムを運転シミュレーションスタディに適用するオプションも提供します。しかし、手頃な価格のため、ここで紹介するドライビングシミュレーションソフトウェアとハードウェアは、他の忠実度の高い商用ドライビングシミュレータと完全に競合することができない可能性があることに注意することが重要です。それにもかかわらず、このプロトコルは、一般的な高忠実度の商業運転シミュレータに代わる手頃な価格でユーザーフレンドリーな代替手段として機能することができます。

Introduction

2016年にグローバルヘルスの推計が明らかにしたデータによると、交通傷害は世界で死亡した8番目の原因であり、世界中で140万人の死亡につながっています。2018年の交通事故の39.2%が輸送中の自動車との衝突で、そのうち7.2%が追突事故でした。車両および交通安全を高めるソリューションは、潜在的な危険を伴うドライバーに警告する高度運転支援システム(ADAS)の開発です。データは、ADASが追突衝突の速度を大幅に減少させることができることを示しており、オートブレーキシステム2を装備するとさらに効果的です。また、自律走行車の開発に伴い、車両の制御に人的関与が少なくなり、自律走行車が自らを規制できない場合に引き継ぎ要求(TOR)警告システムが必要になります。ADASおよびTOR警告システムの設計は、数秒以内に差し迫った事故を回避するために、ドライバーにとって重要な技術の一部となっています。例示的な実験では、振動ツールキットとドライビングシミュレーションプラットフォームを使用して、潜在的なADASおよびTOR警告システムとしてvibrotactile警告システムが使用されたときに最良の結果を生成する場所を調査しました。

知覚チャネルによって分類される警告モダリティには、一般的に、視覚、聴覚、および触覚の 3 種類があります。各警告モダリティには、独自のメリットと制限があります。視覚警告システムが使用されている場合、ドライバーは目視過負荷3に苦しむことがあり、不注意失明4、5による運転性能を損なう可能性があります。聴覚警告システムは、ドライバーの視野に影響を与えませんが、その有効性は、6,7の運転環境におけるバックグラウンドミュージックやその他の騒音などの環境に大きく依存します。したがって、他の外部聴覚情報や重大な騒音を含む状況は、不注意難聴8、9をもたらし、聴覚警告システムの有効性を低下させる可能性があります。それに比べて、触覚警告システムはドライバーの視覚または聴覚処理と競合しません。ドライバーにバイブロタイル警告を送信することにより、触覚警告システムは、視覚および聴覚警告システムの限界を克服します。

以前の研究では、触覚警告はブレーキ応答時間を短縮することによってドライバーに利益をもたらすことが示されました。また、触覚警報システムは、特定の状況で視覚10、11および聴覚12、13、14の警告システムよりもより効果的な結果をもたらすことも判明した。しかし、限られた研究は、触覚警告装置を配置するための最適な場所を調査することに焦点を当てています。感覚皮質仮説15と感覚距離仮説16によると、例示的研究は触覚警告装置を配置するための実験場所として指、手首、および寺院領域を選択した。導入されたプロトコルにより、振動警告の周波数および送達時間、および振動ツールキットの振動間の間隔を、実験要件に合わせて構成することができる。この振動ツールキットは、マスターチップ、電圧レギュレータチップ、マルチプレクサ、USB-トランジスタ-トランジスタロジック(TTL)アダプタ、金属酸化物半導体電界効果トランジスタ(MOSFET)、およびBluetoothモジュールで構成されていました。振動モジュールの数は研究者のニーズに応じて異なり、最大4つのモジュールが同時に振動します。駆動関連実験に振動ツールキットを実装する場合、駆動シミュレーションのコードを改訂することにより、実験設定に適合するとともに、運転性能データと同期するように構成することができる。

研究者にとっては、仮想プラットフォームで運転実験を行うことは、リスクとコストが伴うため、現実の世界よりも実現可能です。たとえば、パフォーマンス指標の収集は困難であり、実際の世界で実験を行っている場合に関連する環境要因を制御することは困難です。その結果、近年、多くの研究では、オンロード走行研究を行うための代替手段として、PC上で実行されている固定ベースのドライビングシミュレータを使用しています。11年以上にわたり、運転研究コミュニティで学習、開発、研究を行った後、オープンソースのドライビングシミュレーションソフトウェアと、ステアリングホイールとギアボックス、3台のペダル、3台の搭載プロジェクター、3つのプロジェクタースクリーンなど、ハードウェアキットで構成された実車で運転シミュレーションプラットフォームを確立しました。ドライビングシミュレーションソフトウェアは単一の画面のみをサポートしており、提示されたプロトコルは中央プロジェクターとプロジェクタ画面のみを使用して実験を行いました。

提示された運転シミュレーションプラットフォームを使用する2つの大きな利点があります。このプラットフォームの利点の 1 つは、オープンソース ソフトウェアを使用することです。研究者は、使いやすいオープンソースプラットフォームを使用して、コード開発なしで簡単なソフトウェア構成を行うことで、独自の研究ニーズに合わせてシミュレーションと振動ツールキットをカスタマイズできます。コードを改訂することで、研究者は、車の種類、道路の種類、ステアリングホイールの抵抗、横方向および縦方向の風の乱流、外部ソフトウェア同期のための時間およびブレーキイベントアプリケーションプログラムインターフェイス(API)、および自動車フォロータスクやNバックタスクなどの行動パラダイムの実装に利用可能な多くのオプションを備えた、現実に相対的な忠実度を提供する運転シミュレーションを作成することができます。運転シミュレータで運転関連の研究を行うことは現実の世界での運転を完全に再現することはできませんが、運転シミュレータを通して収集されたデータは合理的であり、研究者17,18に広く採用されています。

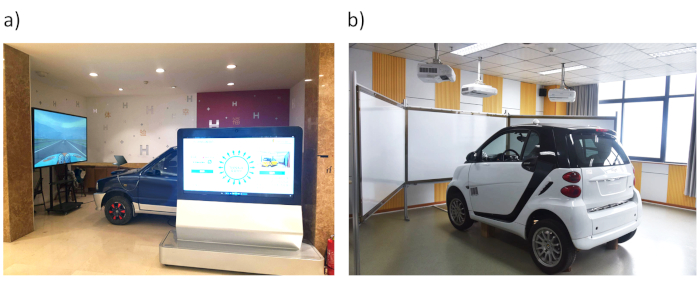

提案されたドライビングシミュレータのもう一つの利点は、その低コストです。前述のように、導入されたドライビングシミュレーションソフトウェアは、ユーザーが無料で利用できるオープンソースソフトウェアです。さらに、このプロトコルでのハードウェア全体のセットアップの総コストは、典型的な高忠実度の商用ドライビングシミュレータと比較して低くなります。図 1 a と b は、3000 ドルから 30000 ドルまでのコストで 2 つのドライビング シミュレータの完全なセットアップを示しています。対照的に、典型的な高忠実度の商業運転シミュレータ(固定ベース)は、通常約$ 10,000から$100,000の費用がかかります。その非常に手頃な価格で、このドライビングシミュレータは、学術研究の目的だけでなく、運転クラス19を実施し、運転関連技術20、21のデモンストレーションのために人気のある選択肢になることができます。

図1:運転シミュレータの画像。両方のドライビングシミュレータは、ステアリングホイールとギアボックス、3つのペダル、および車両で構成されていました。(a) 解像度が 3840 × 2160 の 80 インチ LCD スクリーンを使用した 3000 ドルのドライビング シミュレータ セットアップ。(b) 30000ドルのドライビングシミュレータセットアップで、3台の搭載プロジェクターと3つのプロジェクタースクリーンをそれぞれ223 x 126 cmの寸法で使用しました。投影スクリーンは地上60cm、車両前部から22cm離れた場所に設置した。現在の実験には、中央のプロジェクターとプロジェクター画面のみが使用されました。 この図の大きなバージョンを表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

提案された方法における駆動シミュレーションソフトウェアと振動ツールキットは、我々の研究者22、23、24、25、26、27、28、29によって以前の研究ですでに使用されています。ISO規格30に準拠したこの自己開発振動ツールキットは、振動周波数と強度を調整することにより、異なるフィールド31、32に適用することができる。振動ツールキットの新しいバージョンが開発され、次のプロトコルで導入されることに注意することが重要です。調整可能な電圧アダプタを使用して振動周波数を調整する代わりに、新しいバージョンには5つの異なる振動周波数が装備されており、補足符号化ファイル1に記載されているコードを使用して簡単に調整できます。また、本発表のドライビングシミュレータは、安全で安価で効果的な方法で、さまざまな運転関連の研究を研究します。したがって、このプロトコルは、限られた予算を持ち、実験運転環境をカスタマイズする強い必要性を持っている研究所に適しています。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

ドライビングシミュレーションプラットフォームと振動ツールキットは、実際の生活の中で潜在的なウェアラブルvibrotactileデバイスのアプリケーションを合理的に模倣し、運転関連の研究を調査する上で効果的な技術を提供しました。この技術を使用すると、高い構成性と手頃な価格の安全な実験環境が、現実世界の運転に匹敵する研究を行うことができます。

より注?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

このプロジェクトは北京人材財団が主催しています。

Materials

| Logitech G29 | Logitech | 941-000114 | Steering wheel and pedals |

| Projector screens | – | – | The projector screen for showing the simulation enivronemnt. |

| Epson CB-700U Laser WUXGA Education Ultra Short Focus Interactive Projector | EPSON | V11H878520W | The projector model for generating the display of the simlution enivronment. |

| The Open Racing Car Simulator (TORCS) | – | None | Driving simulation software. The original creators are Eric Espié and Christophe Guionneau, and the version used in experiment is modified by Cao, Shi. |

| Tactile toolkit | Hao Xing Tech. | None | This is used to initiate warnings to the participants. |

| Connecting program (Python) | – | – | This is used to connect the TORCS with the tactile toolkit to send the vibrating instruction. |

| G*power | Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf | None | This software is used to calculate the required number of participants. |

References

- The top 10 causes of death. World Health Organization Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (2018)

- . Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) Available from: https://www.iihs.org/news/detail/gm-front-crash-prevention-systems-cut-police-reported-crashes (2018)

- Spence, C., Ho, C. Tactile and multisensory spatial warning signals for drivers. IEEE Transactions on Haptics. 1 (2), 121-129 (2008).

- Simons, D. J., Ambinder, M. S. Change blindness: theory and consequences. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 14 (1), 44-48 (2005).

- Mack, A., Rock, I. . Inattentional blindness. , (1998).

- Wilkins, P. A., Acton, W. I. Noise and accidents – A review. The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. 25 (3), 249-260 (1982).

- Mohebbi, R., Gray, R., Tan, H. Driver reaction time to tactile and auditory rear-end collision warnings while talking on a cell phone. Human Factors. 51 (1), 102-110 (2009).

- Macdonald, J. S. P., Lavie, N. Visual perceptual load induces inattentional deafness. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics. 73 (6), 1780-1789 (2011).

- Parks, N. A., Hilimire, M. R., Corballis, P. M. Visual perceptual load modulates an auditory microreflex. Psychophysiology. 46 (3), 498-501 (2009).

- Van Erp, J. B. F., Van Veen, H. A. H. C. Vibrotactile in-vehicle navigation system. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 7 (4), 247-256 (2004).

- Lylykangas, J., Surakka, V., Salminen, K., Farooq, A., Raisamo, R. Responses to visual, tactile and visual–tactile forward collision warnings while gaze on and off the road. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 40, 68-77 (2016).

- Halabi, O., Bahameish, M. A., Al-Naimi, L. T., Al-Kaabi, A. K. Response times for auditory and vibrotactile directional cues in different immersive displays. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. 35 (17), 1578-1585 (2019).

- Geitner, C., Biondi, F., Skrypchuk, L., Jennings, P., Birrell, S. The comparison of auditory, tactile, and multimodal warnings for the effective communication of unexpected events during an automated driving scenario. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 65, 23-33 (2019).

- Scott, J., Gray, R. A comparison of tactile, visual, and auditory warnings for rear-end collision prevention in simulated driving. Human Factors. 50, 264-275 (2008).

- Schott, G. D. Penfield’s homunculus: a note on cerebral cartography. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 56 (4), 329-333 (1993).

- Harrar, V., Harris, L. R. Simultaneity constancy: detecting events with touch and vision. Experimental Brain Research. 166 (34), 465-473 (2005).

- Kaptein, N. A., Theeuwes, J., van der Horst, R. Driving simulator validity: Some considerations. Transportation Research Record. 1550 (1), 30-36 (1996).

- Reed, M. P., Green, P. A. Comparison of driving performance on-road and in a low-cost simulator using a concurrent telephone dialling task. Ergonomics. 42 (8), 1015-1037 (1999).

- Levy, S. T., et al. Designing for discovery learning of complexity principles of congestion by driving together in the TrafficJams simulation. Instructional Science. 46 (1), 105-132 (2018).

- Lehmuskoski, V., Niittymäki, J., Silfverberg, B. Microscopic simulation on high-class roads: Enhancement of environmental analyses and driving dynamics: Practical applications. Transportation Research Record. 1706 (1), 73-81 (2000).

- Onieva, E., Pelta, D. A., Alonso, J., Milanes, V., Perez, J. A modular parametric architecture for the TORCS racing engine. 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Games. , 256-262 (2009).

- Zhu, A., Cao, S., Yao, H., Jadliwala, M., He, J. Can wearable devices facilitate a driver’s brake response time in a classic car-following task. IEEE Access. 8, 40081-40087 (2020).

- Deng, C., Cao, S., Wu, C., Lyu, N. Modeling driver take-over reaction time and emergency response time using an integrated cognitive architecture. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2673 (12), 380-390 (2019).

- Deng, C., Cao, S., Wu, C., Lyu, N. Predicting drivers’ direction sign reading reaction time using an integrated cognitive architecture. IET Intelligent Transport Systems. 13 (4), 622-627 (2019).

- Guo, Z., Pan, Y., Zhao, G., Cao, S., Zhang, J. Detection of driver vigilance level using EEG signals and driving contexts. IEEE Transactions on Reliability. 67 (1), 370-380 (2018).

- Cao, S., Qin, Y., Zhao, L., Shen, M. Modeling the development of vehicle lateral control skills in a cognitive architecture. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 32, 1-10 (2015).

- Cao, S., Qin, Y., Jin, X., Zhao, L., Shen, M. Effect of driving experience on collision avoidance braking: An experimental investigation and computational modelling. Behaviour & Information Technology. 33 (9), 929-940 (2014).

- He, J., et al. Texting while driving: Is speech-based text entry less risky than handheld text entry. Accident; Analysis and Prevention. 72, 287-295 (2014).

- Cao, S., Qin, Y., Shen, M. Modeling the effect of driving experience on lane keeping performance using ACT-R cognitive architecture. Chinese Science Bulletin (Chinese Version). 58 (21), 2078-2086 (2013).

- Hsu, W., et al. Controlled tactile and vibration feedback embedded in a smart knee brace. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine. 9 (1), 54-60 (2020).

- Dim, N. K., Ren, X. Investigation of suitable body parts for wearable vibration feedback in walking navigation. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 97, 34-44 (2017).

- Kenntner-Mabiala, R., Kaussner, Y., Jagiellowicz-Kaufmann, M., Hoffmann, S., Krüger, H. -. P. Driving performance under alcohol in simulated representative driving tasks: an alcohol calibration study for impairments related to medicinal drugs. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 35 (2), 134-142 (2015).

- . Royal Meteorological Society Available from: https://www.rmets.org/resource/beaufort-scale (2018)

- Kubose, T. T., et al. The effects of speech production and speech comprehension on simulated driving performance. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 20 (1), (2006).

- He, J., Mccarley, J. S., Kramer, A. F. Lane keeping under cognitive load: performance changes and mechanisms. Human Factors. 56 (2), 414-426 (2014).

- Radlmayr, J., Gold, C., Lorenz, L., Farid, M., Bengler, K. How traffic situations and non-driving related tasks affect the take-over quality in highly automated driving. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 58, 2063-2067 (2014).

- Cao, S., Liu, Y. Queueing network-adaptive control of thought rational (QN-ACTR): an integrated cognitive architecture for modelling complex cognitive and multi-task performance. International Journal of Human Factors Modelling and Simulation. 4, 63-86 (2013).

- Ackerley, R., Carlsson, I., Wester, H., Olausson, H., Backlund Wasling, H. Touch perceptions across skin sites: differences between sensitivity, direction discrimination and pleasantness. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 8 (54), 1-10 (2014).

- Novich, S. D., Eagleman, D. M. Using space and time to encode vibrotactile information: toward an estimate of the skin’s achievable throughput. Experimental Brain Research. 233 (10), 2777-2788 (2015).

- Gilhodes, J. C., Gurfinkel, V. S., Roll, J. P. Role of ia muscle spindle afferents in post-contraction and post-vibration motor effect genesis. Neuroscience Letters. 135 (2), 247-251 (1992).

- Strayer, D. L., Drews, F. A., Crouch, D. J. A comparison of the cell phone driver and the drunk driver. Human Factors. 48 (2), 381-391 (2006).

- Olejnik, S., Algina, J. Measures of effect size for comparative studies: applications, interpretations, and limitations. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 25 (3), 241-286 (2000).

- . Statistics Teacher Available from: https://www.statisticsteacher.org/2017/09/15/what-is-power/ (2017)

- Maurya, A., Bokare, P. Study of deceleration behaviour of different vehicle types. International Journal for Traffic and Transport Engineering. 2 (3), 253-270 (2012).

- Woodward, K. L. The relationship between skin compliance, age, gender, and tactile discriminative thresholds in humans. Somatosensory & Motor Research. 10 (1), 63-67 (1993).

- Stevens, J. C., Choo, K. K. Spatial acuity of the body surface over the life span. Somatosensory & Motor Research. 13 (2), 153-166 (1996).

- Bhat, G., Bhat, M., Kour, K., Shah, D. B. Density and structural variations of Meissner’s corpuscle at different sites in human glabrous skin. Journal of the Anatomical Society of India. 57 (1), 30-33 (2008).

- Chentanez, T., et al. Reaction time, impulse speed, overall synaptic delay and number of synapses in tactile reaction neuronal circuits of normal subjects and thinner sniffers. Physiology & Behavior. 42 (5), 423-431 (1988).

- van Erp, J. B. F., van Veen, H. A. H. C. A multi-purpose tactile vest for astronauts in the international space station. Proceedings of Eurohaptics. , 405-408 (2003).

- Steffan, H. Accident investigation – determination of cause. Encyclopedia of Forensic Sciences (Second Edition). , 405-413 (2013).

- Galski, T., Ehle, H. T., Williams, J. B. Estimates of driving abilities and skills in different conditions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 52 (4), 268-275 (1998).

- Ihemedu-Steinke, Q. C., et al. Simulation sickness related to virtual reality driving simulation. Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality. , 521-532 (2017).

- Kennedy, R. S., Lane, N. E., Berbaum, K. S., Lilienthal, M. G. Simulator sickness questionnaire: an enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology. 3 (3), 203-220 (1993).

- Armagan, E., Kumbasar, T. A fuzzy logic based autonomous vehicle control system design in the TORCS environment. 2017 10th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ELECO). , 737-741 (2017).

- Hsieh, L., Seaman, S., Young, R. A surrogate test for cognitive demand: tactile detection response task (TDRT). Proceedings of SAE World Congress & Exhibition. , (2015).

- Bruyas, M. -. P., Dumont, L. Sensitivity of detection response task (DRT) to the driving demand and task difficulty. Proceedings of the 7th International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training, and Vehicle Design: Driving Assessment 2013. , 64-70 (2013).

- Conti-Kufner, A., Dlugosch, C., Vilimek, R., Keinath, A., Bengler, K. An assessment of cognitive workload using detection response tasks. Advances in Human Aspects of Road and Rail Transportation. , 735-743 (2012).