Uso de un dispositivo de asistencia ventricular percutánea / sistema de derivación de la aurícula izquierda a la arteria femoral para el shock cardiogénico

Summary

El siguiente artículo describe el procedimiento gradual para la colocación de un dispositivo (por ejemplo, Tandemheart) en el shock cardiogénico (CS) que es un dispositivo percutáneo de asistencia ventricular izquierda (pLVAD) y un sistema de derivación de la arteria auricular izquierda a femoral (LAFAB) que evita y apoya el ventrículo izquierdo (VI) en CS.

Abstract

El sistema de derivación de la arteria auricular izquierda a la arteria femoral (LAFAB) es un dispositivo de soporte circulatorio mecánico (SQM) utilizado en el shock cardiogénico (CS) que evita el ventrículo izquierdo drenando sangre de la aurícula izquierda (LA) y devolviéndola a la circulación arterial sistémica a través de la arteria femoral. Puede proporcionar flujos que van desde 2.5-5 L / min dependiendo del tamaño de la cánula. Aquí, discutimos el mecanismo de acción de LAFAB, los datos clínicos disponibles, las indicaciones para su uso en el shock cardiogénico, los pasos de implantación, la atención post-procedimiento y las complicaciones asociadas con el uso de este dispositivo y su manejo.

También proporcionamos un breve video del componente de procedimiento de la terapia del dispositivo, incluida la preparación previa a la colocación, la colocación percutánea del dispositivo a través de la punción transseptal bajo guía ecocardiográfica y el manejo postoperatorio de los parámetros del dispositivo.

Introduction

El shock cardiogénico (SC) es un estado de hipoperfusión tisular con o sin hipotensión concomitante, en el que el corazón no puede suministrar suficiente sangre y oxígeno para satisfacer las demandas del cuerpo, lo que resulta en insuficiencia orgánica. Se clasifica en estadios A a E por la Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI): estadio A – pacientes en riesgo de SC; estadio B – pacientes en la etapa inicial de CS con hipotensión o taquicardia sin hipoperfusión; estadio C – SC clásico con fenotipo frío y húmedo que requiere inotropos/vasopresores o soporte mecánico para mantener la perfusión; etapa D: deterioro en el soporte médico o mecánico actual que requiere escalamiento a dispositivos más avanzados; y estadio E: incluye pacientes con colapso circulatorio y arritmias refractarias que están experimentando activamente un paro cardíaco con reanimación cardiopulmonar en curso1. Las causas más comunes de SC son el IM agudo (IAM), que representa el 81% de los casos en un análisis notificado recientemente2, y la insuficiencia cardíaca aguda descompensada (ADHF). El SC se caracteriza clásicamente por congestión y alteración de la perfusión, que se manifiesta por presiones de llenado elevadas (presión de cuña capilar pulmonar [PCWP], presión diastólica final del ventrículo izquierdo [LVEDP], presión venosa central [CVP] y presión diastólica final del ventrículo derecho [RVEDP]), disminución del gasto cardíaco (CO), índice cardíaco (IC), gasto de potencia cardíaca (CPO) y mal funcionamiento del órgano final3 . En el pasado, los únicos tratamientos disponibles para el IAM complicado por SC eran la revascularización temprana y el tratamiento médico con inotropos y/o vasopresores4. Más recientemente, con el advenimiento de los dispositivos de soporte circulatorio mecánico (SQM) y el reconocimiento de que la escalada de vasopresores se asocia con un aumento de la mortalidad, se ha producido un cambio de paradigma en el tratamiento de la CS5 relacionada con el IAM y la ADHF5,6.

En la era actual de los dispositivos de asistencia ventricular percutánea (pVAD), hay una serie de plataformas/configuraciones de dispositivos MCS disponibles, que proporcionan soporte circulatorio y ventricular univentricular o biventricular con y sin capacidad de oxigenación7. A pesar de los aumentos constantes en el uso de pVAD para tratar tanto el IAM como el SC ADHF, las tasas de mortalidad se han mantenido en gran medida sin cambios5. Con la evidencia emergente de posibles beneficios clínicos para la descarga temprana del ventrículo izquierdo (VI) en AMI8 y el uso temprano de MCS en AMI CS9, el uso de MCS continúa aumentando.

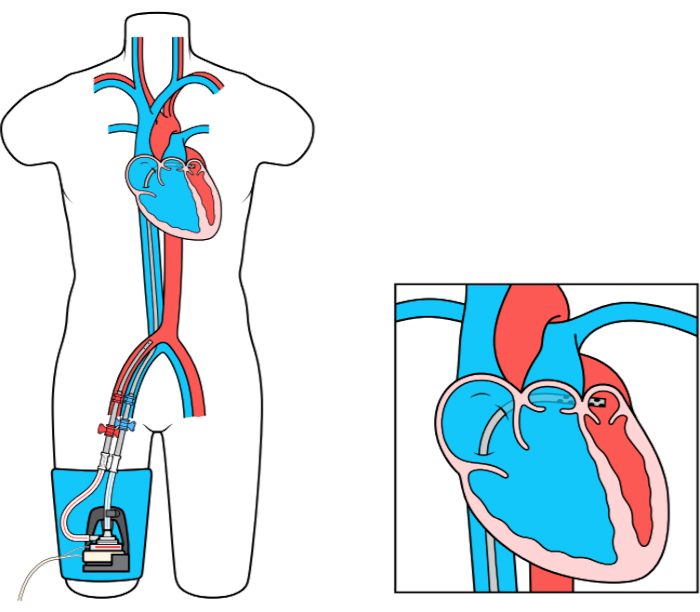

El dispositivo MCS de derivación de la arteria auricular izquierda a femoral (LAFAB) evita el VI drenando la sangre de la aurícula izquierda (LA) y devolviéndola a la circulación arterial sistémica a través de la arteria femoral (Figura 1). Está soportado por una bomba centrífuga externa que ofrece un flujo de 2.5-5.0 litros por minuto (L / m) (bomba de nueva generación, designada como LifeSPARC, capaz de hasta 8 L / m de flujo) dependiendo del tamaño de las cánulas. Una vez que la sangre se extrae de la LA a través de la cánula venosa transseptal, pasa a través de la bomba centrífuga externa que recircula la sangre de nuevo en el cuerpo del paciente a través de la cánula arterial colocada en la arteria femoral.

Figura 1: Configuración de LAFAB. Imagen cortesía de TandemLife, una subsidiaria de propiedad total de LivaNova US Inc. Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

Hemodinámica del dispositivo LAFAB:

El perfil hemodinámico del dispositivo LAFAB es distinto de otros pVAD. Al drenar la sangre directamente de la LA y devolverla a la arteria femoral, el dispositivo evita el VI por completo. Al hacerlo, reduce el volumen y la presión diastólica del extremo del VI, lo que contribuye a mejorar la geometría del VI y, por lo tanto, realiza una disminución en el trabajo de carrera del VI. Sin embargo, al devolver la sangre a la arteria ilíaca / aor…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Al equipo de TandemHeart en LifeSparc.

Materials

| For LAFAB (TandemHeart) | |||

| Factory Supplied Equipment for circuit connections. | TandemLife | ||

| ProtekSolo 15 Fr or 17 Fr Arterial Cannula | TandemLife | ||

| ProtekSolo 62 cm or 72 cm Transseptal Cannula | TandemLife | ||

| TandemHeart Controller | TandemLife | For adjusting flows/RPM | |

| TandemHeart Pump | LifeSPARC | Centrifugal pump | |

| For RAPAB (ProtekDuo) | |||

| Factory Supplied Equipment to complete the circuit. | TandemLife | ||

| ProtekDuo 29 Fr or 31 Fr Dual Lumen Cannula | TandemLife | ||

| TandemHeart Controller | TandemLife | For adjusting flows/RPM | |

| TandemHeart Pump | LifeSPARC | Centrifugal pump |

References

- Baran, D. A., et al. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 94 (1), 29-37 (2019).

- Harjola, V. -. P., et al. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. European Journal of Heart Failure. 17 (5), 501-509 (2015).

- Furer, A., Wessler, J., Burkhoff, D. Hemodynamics of Cardiogenic Shock. Interventional Cardiology Clinics. 6 (3), 359-371 (2017).

- Hochman, J. S., et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction–etiologies, management and outcome: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 36 (3), 1063-1070 (2000).

- Shah, M., et al. Trends in mechanical circulatory support use and hospital mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction and non-infarction related cardiogenic shock in the United States. Clinical Research in Cardiology. 107 (4), 287-303 (2018).

- van Diepen, S., et al. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 136 (16), 232-268 (2017).

- Alkhouli, M., et al. Mechanical Circulatory Support in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 22 (2), 4 (2020).

- Basir, M. B., et al. Feasibility of early mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: The Detroit cardiogenic shock initiative. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 91 (3), 454-461 (2018).

- Basir, M. B., et al. Improved Outcomes Associated with the use of Shock Protocols: Updates from the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 93 (7), 1173-1183 (2019).

- Alkhouli, M., Rihal, C. S., Holmes, D. R. Transseptal Techniques for Emerging Structural Heart Interventions. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 9 (24), 2465-2480 (2016).

- Dennis, C., et al. Clinical use of a cannula for left heart bypass without thoracotomy: experimental protection against fibrillation by left heart bypass. Annals of Surgery. 156 (4), 623-637 (1962).

- Dennis, C., et al. Left atrial cannulation without thoracotomy for total left heart bypass. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. 123, 267-279 (1962).

- Fonger, J. D., et al. Enhanced preservation of acutely ischemic myocardium with transseptal left ventricular assist. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 57 (3), 570-575 (1994).

- Thiele, H., et al. Reversal of cardiogenic shock by percutaneous left atrial-to-femoral arterial bypass assistance. Circulation. 104 (24), 2917-2922 (2001).

- Burkhoff, D., et al. A randomized multicenter clinical study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device versus conventional therapy with intraaortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock. American Heart Journal. 152 (3), 469 (2006).

- Thiele, H., et al. Randomized comparison of intra-aortic balloon support with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with revascularized acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. European Heart Journal. 26 (13), 1276-1283 (2005).

- Gregoric, I. D., et al. TandemHeart as a rescue therapy for patients with critical aortic valve stenosis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 88 (6), 1822-1826 (2009).

- Kar, B., et al. The percutaneous ventricular assist device in severe refractory cardiogenic shock. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 57 (6), 688-696 (2011).

- Patel, C. B., Alexander, K. M., Rogers, J. G. Mechanical Circulatory Support for Advanced Heart Failure. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 12 (6), 549-565 (2010).

- Tempelhof, M. W., et al. Clinical experience and patient outcomes associated with the TandemHeart percutaneous transseptal assist device among a heterogeneous patient population. Asaio Journal. 57 (4), 254-261 (2011).

- Gregoric, I. D., et al. The TandemHeart as a bridge to a long-term axial-flow left ventricular assist device (bridge to bridge). Texas Heart Institute Journal. 35 (2), 125-129 (2008).

- Bruckner, B. A., et al. Clinical experience with the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device as a bridge to cardiac transplantation. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 35 (4), 447-450 (2008).

- Agarwal, R., et al. Successful treatment of acute left ventricular assist device thrombosis and cardiogenic shock with intraventricular thrombolysis and a tandem heart. Asaio Journal. 61 (1), 98-101 (2015).

- Vetrovec, G. W. Hemodynamic Support Devices for Shock and High-Risk PCI: When and Which One. Current Cardiology Reports. 19 (10), 100 (2017).

- Al-Husami, W., et al. Single-center experience with the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device to support patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 20 (6), 319-322 (2008).

- Vranckx, P., et al. Clinical introduction of the Tandemheart, a percutaneous left ventricular assist device, for circulatory support during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. International Journal of Cardiovascular Interventions. 5 (1), 35-39 (2003).

- Vranckx, P., et al. The TandemHeart, percutaneous transseptal left ventricular assist device: a safeguard in high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions. The six-year Rotterdam experience. Euro Intervention. 4 (3), 331-337 (2008).

- Vranckx, P., et al. Assisted circulation using the TandemHeart during very high-risk PCI of the unprotected left main coronary artery in patients declined for CABG. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 74 (2), 302-310 (2009).

- Thomas, J. L., et al. Use of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device for high-risk cardiac interventions and cardiogenic shock. Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 22 (8), 360 (2010).

- Vranckx, P., et al. Assisted circulation using the Tandemhear , percutaneous transseptal left ventricular assist device, during percutaneous aortic valve implantation: the Rotterdam experience. Euro Intervention. 5 (4), 465-469 (2009).

- Pitsis, A. A., et al. Temporary assist device for postcardiotomy cardiac failure. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 77 (4), 1431-1433 (2004).

- Singh, G. D., Smith, T. W., Rogers, J. H. Targeted Transseptal Access for MitraClip Percutaneous Mitral Valve Repair. Interventional Cardiology Clinics. 5 (1), 55-69 (2016).

- Subramaniam, A. V., et al. Complications of Temporary Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support for Cardiogenic Shock: An Appraisal of Contemporary Literature. Cardiology and Therapy. 8 (2), 211-228 (2019).

- Morley, D., et al. Hemodynamic effects of partial ventricular support in chronic heart failure: Results of simulation validated with in vivo data. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 133 (1), 21-28 (2007).

- Naidu, S. S. Novel Percutaneous Cardiac Assist Devices. Circulation. 123 (5), 533-543 (2011).

- Kapur, N. K., et al. Hemodynamic Effects of Left Atrial or Left Ventricular Cannulation for Acute Circulatory Support in a Bovine Model of Left Heart Injury. ASAIO Journal. 61 (3), 301-306 (2015).

- Smith, L., et al. Outcomes of patients with cardiogenic shock treated with TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device: Importance of support indication and definitive therapies as determinants of prognosis. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 92 (6), 1173-1181 (2018).

- Ergle, K., Parto, P., Krim, S. R. Percutaneous Ventricular Assist Devices: A Novel Approach in the Management of Patients With Acute Cardiogenic Shock. The Ochsner Journal. 16 (3), 243-249 (2016).

- Sultan, I., Kilic, A., Kilic, A.Short-Term Circulatory and Right Ventricle Support in Cardiogenic Shock: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Tandem Heart, CentriMag, and Impella. Heart Failure Clinics. 14 (4), 579-583 (2018).

- Bermudez, C., et al. . Percutaneous right ventricular support: Initial experience from the tandemheart experiences and methods (THEME) registry. , (2018).

- Aggarwal, V., Einhorn, B. N., Cohen, H. A. Current status of percutaneous right ventricular assist devices: First-in-man use of a novel dual lumen cannula. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 88 (3), 390-396 (2016).

- Kapur, N. K., et al. Mechanical circulatory support devices for acute right ventricular failure. Circulation. 136 (3), 314-326 (2017).

- Kapur, N. K., et al. Mechanical Circulatory Support for Right Ventricular Failure. JACC: Heart Failure. 1 (2), 127-134 (2013).

- Geller, B. J., Morrow, D. A., Sobieszczyk, P. Percutaneous Right Ventricular Assist Device for Massive Pulmonary Embolism. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 5 (6), 74-75 (2013).

- Bhama, J., et al. Initial Experience with a Percutaneous Dual Lumen Single Cannula Strategy for Temporary Right Ventricular Assist Device Support Following Durable LVAD Therapy. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 35 (4), 323 (2013).

- O’Neill, B., et al. Right ventricular hemodynamic support with the PROTEKDuo Cannula. Initial experience from the tandemheart experiences and methods (THEME) registry category. Miscellaneous. , (2018).

- O’Brien, B., et al. Fluoroscopy-free AF ablation using transesophageal echocardiography and electroanatomical mapping technology. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology. 50 (3), 235-244 (2017).

- O’Brien, B., et al. Transseptal puncture — Review of anatomy, techniques, complications and challenges. International Journal of Cardiology. 233, 12-22 (2017).