远红荧光衰老相关β-半乳糖苷酶探针,用于通过流式细胞术鉴定和富集衰老肿瘤细胞

Summary

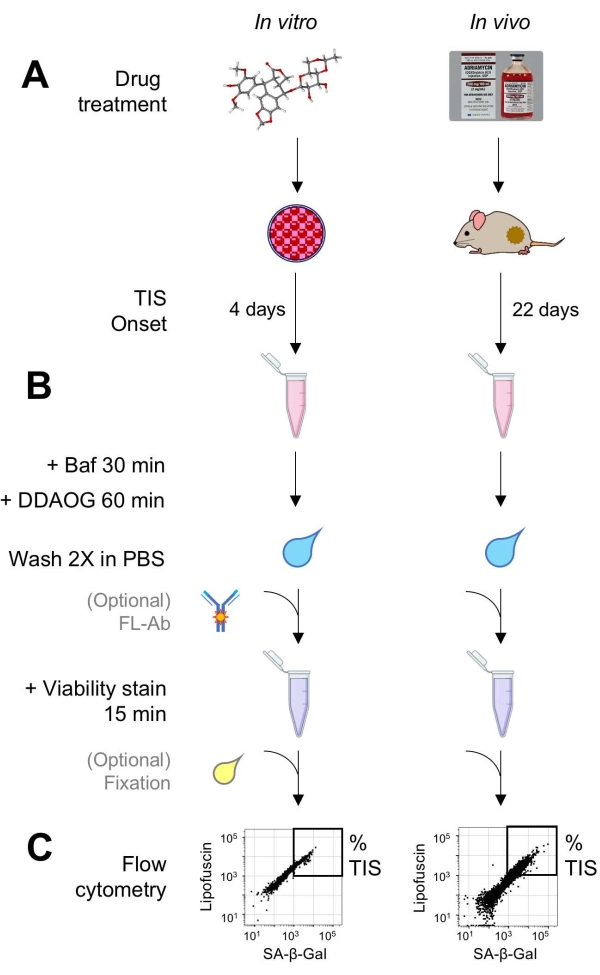

提出了一种荧光流式细胞术定量由细胞培养或小鼠肿瘤模型中化疗药物诱导的衰老癌细胞的方案。可选程序包括共免疫染色、便于大批量或时间点分析的样品固定,以及通过流式细胞术分选富集活衰老细胞。

Abstract

细胞衰老是由生物损伤引起的增殖性停滞状态,通常在衰老细胞中累积多年,但也可能在肿瘤细胞中迅速出现,作为对各种癌症治疗诱导的损伤的反应。肿瘤细胞衰老通常被认为是不可取的,因为衰老细胞对死亡产生抵抗力并阻止肿瘤缓解,同时加剧肿瘤恶性肿瘤和治疗耐药性。因此,衰老肿瘤细胞的鉴定是癌症研究界持续关注的问题。存在各种衰老测定,许多基于众所周知的衰老标志物,衰老相关β-半乳糖苷酶(SA-β-Gal)的活性。

通常,SA-β-Gal测定是在固定细胞上使用显色底物(X-Gal)进行的,通过光学显微镜缓慢而主观地计数“蓝色”衰老细胞。使用细胞渗透性荧光SA-β-Gal底物(包括C12-FDG(绿色)和DDAO-半乳糖苷(DDAOG;远红色))的改进检测能够分析活细胞,并允许使用高通量荧光分析平台,包括流式细胞仪。C12-FDG是SA-β-Gal的有据可查的探针,但其绿色荧光发射与衰老期间由于脂褐素聚集体的积累而产生的固有细胞自发荧光(AF)重叠。通过使用远红SA-β-Gal探针DDAOG,绿色细胞自发荧光可用作确认衰老的次要参数,从而增加测定的可靠性。其余荧光通道可用于细胞活力染色或可选的荧光免疫标记。

使用流式细胞术,我们证明了使用DDAOG和脂褐素自发荧光作为双参数测定来鉴定衰老肿瘤细胞。进行活衰老细胞百分比的定量。如果需要,可以包括可选的免疫标记步骤来评估感兴趣的细胞表面抗原。鉴定出的衰老细胞也可以进行流式细胞术分选和收集以进行下游分析。收集的衰老细胞可以立即裂解(例如,用于免疫测定或“组学分析”)或进一步培养。

Introduction

衰老细胞通常在正常的生物衰老过程中在生物体内积累多年,但也可能在肿瘤细胞中迅速发展,作为对各种癌症治疗(包括放疗和化疗)引起的损伤的反应。虽然不再增殖,但治疗诱导的衰老(TIS)肿瘤细胞可能有助于治疗耐药性并导致复发1,2,3。TIS细胞分泌的因子可以通过促进免疫逃避或转移来加剧肿瘤恶性肿瘤4,5。TIS细胞产生复杂的,上下文特异性表型,改变的代谢谱和独特的免疫反应6,7,8。因此,各种癌症治疗方法诱导的TIS肿瘤细胞的鉴定和表征是癌症研究界持续关注的课题。

为了检测TIS肿瘤细胞,常规衰老测定被广泛使用,主要基于检测衰老标志酶溶酶体β-半乳糖苷酶GLB19的活性增加。在接近中性(而不是酸性)溶酶体 pH 下检测可以特异性检测衰老相关的 β-半乳糖苷酶 (SA-β-Gal)10。已经使用了几十年的标准SA-β-Gal测定使用X-Gal(5-溴-4-氯-3-吲哚基-β-D-吡喃半乳糖苷),一种蓝色显色β-半乳糖苷底物,通过光学显微镜检测固定细胞中的SA-β-Gal11。X-Gal 测定允许使用常用试剂和实验室设备对 TIS 进行定性视觉确认。基本的透射光显微镜是评估蓝色显色原存在所需的唯一仪器。然而,X-Gal 染色程序可能缺乏敏感性,有时需要超过 24 小时才能显色。染色之后,根据在光学显微镜下对表现出一定强度的蓝色色原的细胞进行计数,对单个衰老细胞进行低通量主观评分。由于X-Gal是不可渗透的,因此该测定需要溶剂固定的细胞,这些细胞无法回收用于下游分析。当处理来自动物或患者的有限样本时,这可能是一个主要缺点。

使用细胞通透性荧光酶底物改进的 SA-β-Gal 测定,包括 C 12-FDG(5-十二烷基氨基荧光素 Di-β-D-吡喃半乳糖苷,绿色)和 DDAOG(9H-(1,3-二氯-9,9-二甲基吖啶-2-酮-7-基)β-D-吡喃半乳糖苷,远红色)先前已出现在文献12,13,14,15 中。DDAOG的化学探针结构和光学特性见补充图S1。这些细胞通透性探针允许分析活细胞(而不是固定细胞),荧光探针而不是显色探针有助于使用快速高通量荧光分析平台,包括高内涵筛选仪器和流式细胞仪。分选流式细胞仪能够从细胞培养物或肿瘤中回收富集的活衰老细胞群,以进行下游分析(例如,蛋白质印迹、ELISA或“组学”。荧光分析还提供定量信号,可以更准确地确定给定样品中衰老细胞的百分比。可以轻松添加其他荧光探针,包括活性探针和荧光团标记的抗体,用于SA-β-Gal以外的靶标的多重分析。

与DDAOG类似,C12-FDG是SA-β-Gal的荧光探针,但其绿色荧光发射与内在细胞AF重叠,后者在衰老期间由于细胞16中脂褐素聚集体的积累而产生。通过使用远红DDAOG探针,绿色细胞AF可以用作确认衰老的辅助参数17。这通过在SA-β-Gal之外使用第二个标记物来提高测定可靠性,而SA–Gal作为衰老的单一标记物通常不可靠18。由于检测衰老细胞中的内源性AF是一种无标记的方法,因此它是扩展我们基于DDAOG的测定特异性的快速简便方法。

在该协议中,我们证明了使用DDAOG和AF作为快速,双参数流式细胞术测定,用于鉴定来自 体外 培养物或从小鼠中建立的药物治疗肿瘤中分离的活TIS肿瘤细胞(图1)。该方案使用与各种标准商业流式细胞仪和分选仪兼容的荧光团(表1)。使用标准流式细胞术分析可以定量活衰老细胞的百分比。如果需要,可以执行可选的免疫标记步骤以评估与衰老同时感兴趣的细胞表面抗原。鉴定的衰老细胞也可以使用标准的荧光激活细胞分选(FACS)方法进行富集。

图 1:实验性工作流程。 总结DDAOG测定关键点的示意图。(A)将TIS诱导药物添加到哺乳动物培养的细胞中或施用于荷瘤小鼠。然后允许时间用于TIS的发作:对于细胞,治疗后4天;对于小鼠,总共22天,每5天进行三次治疗,外加7天恢复。收获细胞或将肿瘤解离成悬浮液。(B)用Baf处理样品以调节溶酶体pH以检测SA-β-Gal30分钟;然后,加入DDAOG探针60分钟以检测SA-β-Gal。将样品在PBS中洗涤2次,并短暂添加活性染色剂(15分钟)。或者,样品可以在开放的荧光通道中用荧光抗体染色和/或固定以供以后分析。(C)使用标准流式细胞仪分析样品。活细胞在点图中可视化,显示红色DDAOG(指示SA-β-Gal)与绿色自发荧光(脂褐素)。基于未处理的对照样品(未显示)建立确定TIS细胞百分比的门。如果使用分选细胞仪(FACS),则可以收集TIS细胞并将其放回培养物中以进行进一步的 体外 测定,或者裂解并处理以进行分子生物学测定。缩写:DDAO = 9H-(1,3-二氯-9,9-二甲基吖啶-2-酮);DDAOG = DDAO-半乳糖苷;TIS=治疗诱导的衰老;FL-Ab = 荧光团偶联抗体;Baf = 巴非霉素 A1;SA-β-Gal = 衰老相关的 β-半乳糖苷酶;PBS = 磷酸盐缓冲盐水;FACS = 荧光激活细胞分选。 请点击此处查看此图的大图。

| 荧光基团 | 检测 | 防爆/电磁(纳米) | 激光细胞仪(纳米) | 细胞仪检测器/带通滤光片(纳米) |

| 东道格 | SA-β-加尔 | 645/6601 | 640 | 670 / 30 |

| 自动对焦 | 脂褐素 | < 600 | 488 | 525 / 50 |

| CV450 | 可行性 | 408/450 | 405 | 450 / 50 |

| 体育 | 抗体/表面标志物 | 565/578 | 561 | 582 / 15 |

表 1:荧光团和细胞仪光学规格。 本协议中使用的细胞仪规格列出了总共具有 4 个激光器和 15 个发射检测器的仪器。在 645/660 nm 处检测到的 DDAOG 是被 SA-β-Gal1 切割的探针的形式。未裂解的DDAOG可以在460/610nm处表现出低水平的荧光,但通过方案中的洗涤步骤去除。缩写:DDAO = 9H-(1,3-二氯-9,9-二甲基吖啶-2-酮);DDAOG = DDAO-半乳糖苷;AF = 自发荧光;PE = 藻红蛋白;SA-β-Gal = 衰老相关的 β-半乳糖苷酶。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

在过去十年左右的时间里,由于肿瘤免疫学的日益普及,低成本流式细胞仪的发展以及学术机构共享仪器设施的改进,流式细胞术已成为癌症研究中更常见的分析平台。多色检测现在是标准配置,因为大多数较新的仪器都配备了紫色、蓝绿色和红色至远红色的光学阵列。因此,该DDAOG方案可能与各种流式细胞仪兼容。当然,任何流式细胞仪都应经过用户评估。在DDAOG测定中添加额外的荧光团(例如…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

我们感谢芝加哥大学的细胞术和抗体核心设施对流式细胞术仪器的支持。芝加哥大学的动物研究中心提供动物住房。

Materials

| Bafilomycin A1 | Research Products International | B40500 | |

| Bleomycin sulfate | Cayman | 13877 | |

| Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | US Biological | A1380 | |

| Calcein Violet 450 AM viability dye | ThermoFisher Scientific | 65-0854-39 | eBioscience |

| DPP4 antibody, PE conjugate | Biolegend | 137803 | Clone H194-112 |

| Cell line: A549 human lung adenocarcinoma | American Type Culture Collection | CCL-185 | |

| Cell line: B16-F10 mouse melanoma | American Type Culture Collection | CRL-6475 | |

| Cell scraper | Corning | 3008 | |

| Cell strainers, 100 µm | Falcon | 352360 | |

| DDAO-Galactoside | Life Technologies | D6488 | |

| DMEM medium 1x | Life Technologies | 11960-069 | |

| DMSO | Sigma | D2438 | |

| DNAse I | Sigma | DN25 | |

| Doxorubicin, hydrochloride injection (USP) | Pfizer | NDC 0069-3032-20 | |

| Doxorubicin, PEGylated liposomal (USP) | Sun Pharmaceutical | NDC 47335-049-40 | |

| EDTA 0.5 M | Life Technologies | 15575-038 | |

| Etoposide | Cayman | 12092 | |

| FBS | Omega | FB-11 | |

| Fc receptor blocking reagent | Biolegend | 101320 | Anti-mouse CD16/32 |

| Flow cytometer (cell analyzer) | Becton Dickinson (BD) | Various | LSRFortessa |

| Flow cytometer (cell sorter) | Becton Dickinson (BD) | Various | FACSAria |

| GlutaMax 100x | Life Technologies | 35050061 | |

| HEPES 1 M | Lonza | BW17737 | |

| Liberase TL | Sigma | 5401020001 | Roche |

| Paraformaldehyde 16% | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 15710 | |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin 100x | Life Technologies | 15140122 | |

| Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) 1x | Corning | MT21031CV | Dulbecco's PBS (without calcium and magnesium) |

| Rainbow calibration particles, ultra kit | SpheroTech | UCRP-38-2K | 3.5-3.9 µm, 2E6/mL |

| RPMI-1640 medium 1x | Life Technologies | 11875-119 | |

| Sodium chloride 0.9% (USP) | Baxter Healthcare Corporation | 2B1324 | |

| Software for cytometer data acquisition, "FACSDiva" | Becton Dickinson (BD) | n/a | Contact BD for license |

| Software for cytometer data analysis, "FlowJo" | TreeStar | n/a | Contact TreeStar for license |

| Trypsin-EDTA 0.25% | Life Technologies | 25200-114 |

References

- Saleh, T., Tyutyunyk-Massey, L., Gewirtz, D. A. Tumor cell escape from therapy-induced senescence as a model of disease recurrence after dormancy. 암 연구학. 79 (6), 1044-1046 (2019).

- Wang, B., Kohli, J., Demaria, M. Senescent cells in cancer therapy: friends or foes. Trends in Cancer. 6 (10), 838-857 (2020).

- Prasanna, P. G., et al. Therapy-induced senescence: Opportunities to improve anticancer therapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 113 (10), 1285-1298 (2021).

- Velarde, M. C., Demaria, M., Campisi, J. Senescent cells and their secretory phenotype as targets for cancer therapy. Interdisciplinary Topics in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 38, 17-27 (2013).

- Ou, H. L., et al. Cellular senescence in cancer: from mechanisms to detection. Molecular Oncology. 15 (10), 2634-2671 (2021).

- Hernandez-Segura, A., Nehme, J., Demaria, M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends in Cell Biology. 28 (6), 436-453 (2018).

- Bojko, A., Czarnecka-Herok, J., Charzynska, A., Dabrowski, M., Sikora, E. Diversity of the senescence phenotype of cancer cells treated with chemotherapeutic agents. Cells. 8 (12), 1501 (2019).

- Mikuła-Pietrasik, J., Niklas, A., Uruski, P., Tykarski, A., Książek, K. Mechanisms and significance of therapy-induced and spontaneous senescence of cancer cells. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 77 (2), 213-229 (2020).

- Lee, B. Y., et al. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase. Aging cell. 5 (2), 187-195 (2006).

- Itahana, K., Itahana, Y., Dimri, G. P. Colorimetric detection of senescence-associated β galactosidase. Methods in Molecular Biology. 965, 143-156 (2013).

- Dimri, G. P., et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (20), 9363-9367 (1995).

- Debacq-Chainiaux, F., Erusalimsky, J. D., Campisi, J., Toussaint, O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nature Protocols. 4 (12), 1798-1806 (2009).

- Noppe, G., et al. Rapid flow cytometric method for measuring senescence associated beta-galactosidase activity in human fibroblasts. Cytometry A. 75 (11), 910-916 (2009).

- Tung, C. -. H., et al. In vivo imaging of β-galactosidase activity using far red fluorescent switch. 암 연구학. 64 (5), 1579-1583 (2004).

- Gong, H., et al. beta-Galactosidase activity assay using far-red-shifted fluorescent substrate DDAOG. Analytical Biochemistry. 386 (1), 59-64 (2009).

- Terman, A., Brunk, U. T. Lipofuscin: Mechanisms of formation and increase with age. APMIS. 106 (2), 265-276 (1998).

- Georgakopoulou, E. A., et al. Specific lipofuscin staining as a novel biomarker to detect replicative and stress-induced senescence. A method applicable in cryo-preserved and archival tissues. Aging. 5 (1), 37-50 (2013).

- Wang, B., Demaria, M. The quest to define and target cellular senescence in cancer. 암 연구학. 81 (24), 6087-6089 (2021).

- Appelbe, O. K., Zhang, Q., Pelizzari, C. A., Weichselbaum, R. R., Kron, S. J. Image-guided radiotherapy targets macromolecules through altering the tumor microenvironment. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 13 (10), 3457-3467 (2016).

- Maciorowski, Z., Chattopadhyay, P. K., Jain, P. Basic multicolor flow cytometry. Current Protocols in Immunology. 117, 1-38 (2017).

- Fan, Y., Cheng, J., Zeng, H., Shao, L. Senescent cell depletion through targeting BCL-family proteins and mitochondria. Frontiers in Physiology. 11, 593630 (2020).

- Kim, K. M., et al. Identification of senescent cell surface targetable protein DPP4. Genes and Development. 31 (15), 1529-1534 (2017).

- Flor, A. C., Kron, S. J. Lipid-derived reactive aldehydes link oxidative stress to cell senescence. Cell Death Discovery. 7 (9), 2366 (2016).

- Jochems, F., et al. The Cancer SENESCopedia: A delineation of cancer cell senescence. Cell reports. 36 (4), 109441 (2021).

- Fallah, M., et al. Doxorubicin and liposomal doxorubicin induce senescence by enhancing nuclear factor kappa B and mitochondrial membrane potential. Life Sciences. 232, 116677 (2019).

- Kasper, M., Barth, K. Bleomycin and its role in inducing apoptosis and senescence in lung cells – modulating effects of caveolin-1. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 9 (3), 341-353 (2009).

- Muthuramalingam, K., Cho, M., Kim, Y. Cellular senescence and EMT crosstalk in bleomycin-induced pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis-an in vitro analysis. Cell Biology International. 44 (2), 477-487 (2020).

- Flor, A. C., Wolfgeher, D., Wu, D., Kron, S. J. A signature of enhanced lipid metabolism, lipid peroxidation and aldehyde stress in therapy-induced senescence. Cell Death Discovery. 3, 17075 (2017).

- Burd, C. E., et al. Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16(INK4a)-luciferase model. Cell. 152 (1-2), 340-351 (2013).

- Liu, J. Y., et al. Cells exhibiting strong p16 (INK4a) promoter activation in vivo display features of senescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (7), 2603-2611 (2019).

- Wang, L., Lankhorst, L., Bernards, R. Exploiting senescence for the treatment of cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 22 (6), 340-355 (2022).

- Baek, K. -. H., Ryeom, S. Detection of oncogene-induced senescence in vivo. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1534, 185-198 (2017).

- González-Gualda, E., Baker, A. G., Fruk, L., Muñoz-Espín, D. A guide to assessing cellular senescence in vitro and in vivo. The FEBS Journal. 288 (1), 56-80 (2021).