Conjugaison : méthode de transfert de la résistance à l'ampicilline du donneur à l'hôte E. coli

English

소셜에 공유하기

개요

Source: Alexander S. Gold1, Tonya M. Colpitts1

1 Département de microbiologie, Boston University School of Medicine, National Emerging Infections Diseases Laboratories, Boston, MA

Découverte pour la première fois par Lederberg et Tatum en 1946, la conjugaison est une forme de transfert horizontal de gènes entre bactéries qui repose sur un contact physique direct entre deux cellules bactériennes (1). Contrairement à d’autres formes de transfert de gènes, comme la transformation ou la transduction, la conjugaison est un processus naturel dans lequel l’ADN est sécrété d’une cellule de donneur à une cellule recevable d’une manière unidirectionnelle. Cette directionnalité et la capacité de ce processus d’augmenter la diversité génétique des bactéries a donné à la conjugaison la réputation comme une forme d’« accouplement » bactérien, qui aurait grandement contribué à l’augmentation récente de la résistance aux antibiotiques. bactéries (2, 3). En utilisant des pressions sélectives, par exemple l’utilisation d’antibiotiques, la conjugaison a été manipulée pour une utilisation en laboratoire, ce qui en fait un outil puissant pour le transfert horizontal de gènes entre les bactéries, et dans certains cas des bactéries à la levure, les plantes et les animaux cellules (4). Outre les applications en laboratoire, le transfert de gène bactérierium-eucaryote par conjugaison est une avenue passionnante de transfert d’ADN avec une multitude d’applications biotechniques possibles et des implications naturelles (5).

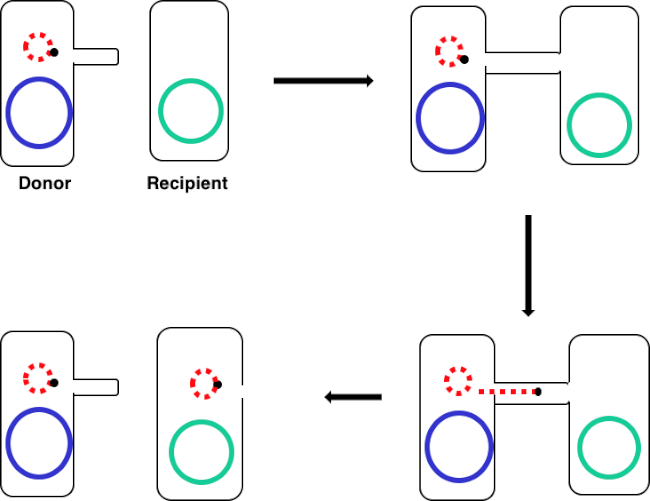

On pense que la conjugaison fonctionne par un « mécanisme en deux étapes » (6). Tout d’abord, avant que l’ADN puisse être transféré, la cellule du donneur doit établir un contact direct de cellule à cellule avec le receveur. Ce processus a été caractérisé le mieux dans les bactéries gram-négatives, dont la plus étudiée est Escherichia coli. Le contact cellule-cellule est établi par la présence d’un réseau complexe de filaments extracellulaires sur le donneur connu sous le nom de pilus sexuel, un élément conjugal codé par le gène transférable connu sous le nom de facteur F (fertilité) (7, 8). En plus d’établir le contact entre le donneur et le receveur, plusieurs protéines sont transportées par le pilus sexuel au cytoplasme receveur, formant un conduit de système de sécrétion de type IV (T4SS) entre les deux cellules, une structure nécessaire pour la deuxième étape de conjugaison, transfert d’ADN (6). En combinant cette fonction du pilus sexuel avec la réplication du cercle roulant de l’ADN, la cellule du donneur est capable de transférer l’ADN sous la forme d’un élément transposable, tel qu’un plasmide ou un transposon, au destinataire par un modèle de « tirer et pomper » (6). Dans ce cas, le « tir » est le transport de la protéine pilote, avec l’ADN lié, par le T4SS dans la cellule récepteur, et le « pompage » est le transport actif de l’ADN au destinataire, un processus dépendant du T4SS et catalysé par des protéines de couplage (6). La machinerie utilisée dans ce processus est composée d’une origine de séquence de transfert (oriT), qui doit être fournie par l’ADN dans les gènes cis et trans, qui codent une relaxase, complexe de formation de paire de compagnon, et le type IV protéine de couplage, et peuvent être présents en cis ou trans (9). Cette relaxase fend le site nic dans la séquence oriT et se fixe de façon covalente à l’extrémité 5′ du brin transféré pour produire le relaxosome, un complexe d’ADN-relaxase à brin unique avec d’autres protéines auxiliaires (9). Une fois formé, le relaxosome se connecte au complexe de formation de paires d’accouplement, via la protéine de couplage de type IV, qui permet le transfert du complexe ssDNA-relaxase en cellules réceptrices par le T4SS (10). Une fois dans le cytoplasme du receveur, l’ADN peut s’intégrer dans le génome du receveur ou exister séparément sous la forme d’un plasmide, qui permettent l’expression de ses gènes.

Dans cette expérience, la souche de donneur de conjugaison largement utilisée E. coli WM3064 a été utilisée pour transférer l’encodage génétique pour la résistance à l’ampicilline à la souche bénéficiaire E. coli J53. Tandis que les deux souches des bactéries gram-négatives étaient résistantes à la tétracycline, seulement la souche de distributeur WM3064 a eu le gène pour la résistance d’ampicilline, codépour dans le vecteur de navette de pWD2-oriT, et était auxotrophique à l’acide diaminomiélique (DAP) (11-13). Cette expérience consistait en deux étapes principales, la préparation des souches du donneur et du receveur, suivie du transfert du gène de résistance à l’ampicilline du donneur au receveur par conjugaison (figure 1).

Figure 1 : Schéma de conjugaison. Ce schéma montre le transfert réussi d’un plasmide, un seul exemple d’un élément d’ADN transposable, d’une cellule de donneur à une cellule receveure utilisant la conjugaison. Au contact de la cellule réceptrice par la cellule du donneur par l’intermédiaire du pilus sexuel, le plasmide se reproduit par la réplication du cercle roulant, se déplace à travers le complexe multiprotéiné en joignant les deux cellules, et forme un nouveau plasmide complet dans la cellule réceptrice.

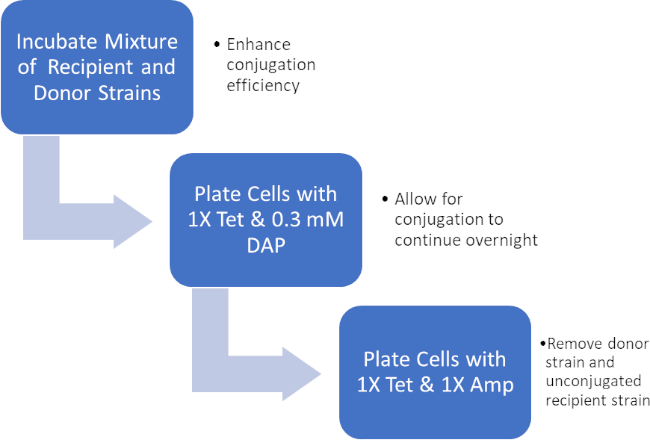

En couvant un mélange de cellules de donneur et de receveur, puis en placageant successivement ces cellules en présence de la tétracycline et du DAP, cela a permis le transfert réussi du gène de résistance à l’ampicilline. Les cellules de placage successivement cultivées à partir de ce mélange en présence de tétracycline et d’ampicilline, enlevé toutes les cellules de donneur en raison de l’absence de DAP et toutes les cellules receveuses qui peuvent ne pas avoir gagné le gène de résistance à l’ampicilline, donnant strictement destinataire J53 souche bactéries qui ont acquis une résistance à l’ampicilline (figure 2). Une fois effectué, le transfert réussi du gène de résistance d’ampicilline a été confirmé par PCR. Depuis que la conjugaison a été réussie, la souche J53 de E. coli a contenu pWD2-oriT et était résistante à l’ampicilline, et l’encodage de gène pour cette résistance est détectable par PCR. Cependant, en cas d’échec, il n’y aurait pas eu de détection du gène de résistance à l’ampicilline et l’ampicilline fonctionnerait toujours comme un antibiotique efficace contre la souche J53.

Figure 2 : Schéma de protocole. Ce schéma montre un aperçu du protocole présenté.

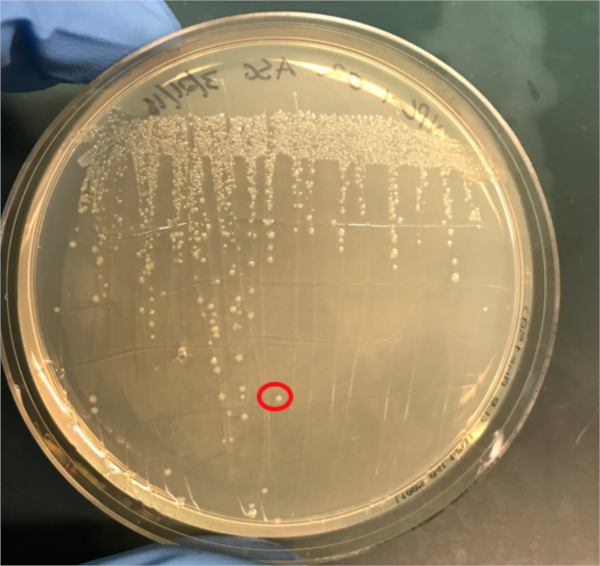

Figure 3A : Confirmation d’une conjugaison réussie par PCR. A) Les stocks de congélation des échantillons témoins conjugués et négatifs ont été striés sur des plaques d’agar et une colonie a été sélectionnée (rouge) pour l’isolement de l’ADN.

Procedure

Results

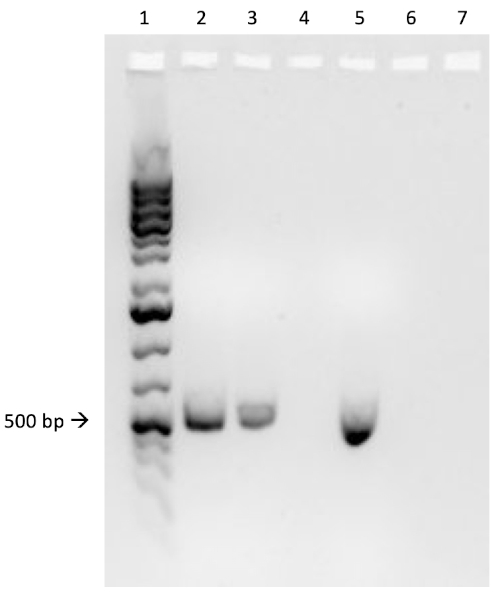

If conjugation was successful, a 500 base-pair sized band PCR product will be observed in the well in which PCR reaction 1 was loaded (Well #2 in Figure 3B), while no bands will be observed in the well in which PCR reaction 3 was loaded (Well #4 in Figure 3B). The presence of this band confirms the successful transfer of the ampicillin resistance gene, thereby conferring ampicillin resistance to the J53 strain of E. coli.

Figure 3B: The confirmation of successful conjugation by PCR. B) PCR analysis was done using DNA isolated from the select colony. The contents of each well are as follows: 1) DNA ladder, 2) Conjugation DNA and ampicillin primers, 3) Conjugation DNA and housekeeping primers, 4) Negative control DNA and ampicillin primers, 5) Negative control DNA and housekeeping primers, 6) No DNA and ampicillin primers, and 7) No DNA and negative control primers. The presence of a ~ 500 base-pair band PCR product from PCR reaction 1 (well 2), and the lack of this product from PCR reaction 3 (well 4), confirms successful conjugation.

Applications and Summary

Conjugation is a naturally occurring process of horizontal gene transfer that relies on the direct cell-to-cell contact of a donor cell and a recipient cell. This process is shared among all kinds of bacteria and has been instrumental in bacterial evolution, most notably antibiotic resistance. In the lab, conjugation can be used as an effective method of gene transfer that is much less disruptive when compared to other techniques. Outside of the laboratory, the ability to transfer DNA from bacteria to eukaryotes via conjugation offers an exciting new avenue of gene therapy and understanding the implications of these naturally occurring gene transfers, for example the relationship between bacterial infection and cancer, is a rapidly emerging area of research.

References

- Lederberg J, Tatum, E.L. Gene recombination in Escherichia coli Nature. 1946;158:558.

- Holmes R.K. J, M.G. Genetics: Exchange of Genetic Information. 4th Edition ed. Baron S, editor. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

- Cruz F, Davies, J. Horizontal gene transfer and the origin of species: lessons from bacteria. Trends in Microbiology. 2000;8:128-33.

- Llosa M, Cruz, F. Bacterial conjugation: a potential tool for genomic engineering. Ressearch in Microbiology. 2005;156:1-6.

- Lacroix B, Citovsky, V. Transfer of DNA from Bacteria to Eukaryotes. mBio. 2016;7(4):1-9.

- Llosa M, et al. Bacterial conjugation: a two-step mechanism for

- DNA transport. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;45:1-8.

- Grohmann E, Muth, G., Espinosa, M. Conjugative Plasmid Transfer in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2003;67:277-301.

- Firth N, Ippen-Ihler, K, Skurray, RA. Structure and function of the F factor and mechanism of conjugation. Escherichia coli and salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 1996;2:2377-401.

- Smillie C, Garcillan-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EPC, De La Cruz F. Mobility of Plasmids. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010;74(3):434-52.

- Cascales E. Definition of a Bacterial Type IV Secretion Pathway for a DNA Substrate. 2004;304(5674):1170-3.

- Wang P, Yu Z, Li B, Cai X, Zeng Z, Chen X, et al. Development of an efficient conjugation-based genetic manipulation system for Pseudoalteromonas. Microbial Cell Factories. 2015;14(1):11.

- Yi H, Cho YJ, Yong D, Chun J. Genome Sequence of Escherichia coli J53, a Reference Strain for Genetic Studies. Journal of Bacteriology. 2012;194(14):3742-3.

- Baumann RLB, E. H.; Wiseman, J. S.; Vaal, M.; Nichols, J. S. Inhibition of Escherichia coli Growth and Diaminopimelic Acid Epimerase by 3-Chlorodiaminopimelic Acid. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1988;32:1119-23.

- Rocha D, Santos, CS, Pacheco LG. Bacterial reference genes for gene expression studies by RT-qPCR: survey and analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2015;108:685-93.

내레이션 대본

Bacterial cells, such as E. coli, are able to transfer genetic information from cell-to-cell. Conjugation differs from other mechanisms of DNA transfer, such as transduction or transformation, in that it requires physical contact between the cells.

To proceed, conjugation requires a donor cell that expresses the fertility, or F, factor and a recipient cell without it, an F minus cell. The process requires two steps. The first is the establishment of direct cell-to-cell contact. To do this, the donor cell generates an extracellular filamentous structure called a sex pilus. It is named this since conjugation is a form of mating for asexually reproducing bacteria, but it should be noted that it is not true sexual reproduction as no gametes are exchanged and no offspring are formed.

The second step is delivery of DNA to the recipient cell. After the sex pilus establishes contact between two cells, a conduit called the Type IV secretion system is built allowing for the transfer of DNA. The donor cell then begins to replicate the extrachromosomal DNA that will be transferred selected based on the presence of a genetic element known as the OriT or origin of transfer. One end of the newly replicated DNA is threaded into the conduit through DNA protein binding. As the DNA is further replicated, it is pumped through the channel, facilitated by a complex of proteins encoded by genes located close to the OriT. Once the DNA is fully transferred, it will either form an extra chromosomal plasmid, or it may integrate into the chromosome of the recipient cell. Whichever the endpoint of the transferred DNA, the genes it encodes will then be expressed. This gene expression can be used to confirm successful conjugation.

For example, consider a scenario where the donor strain expresses ampicillin resistance and passes this on in the conjugated DNA to the recipient bacterium, but the recipient strain also has a tetracycline resistance gene not present in the donor. In this event, when the cells are plated on LB media containing both tetracycline and ampicillin, colonies should grow only from successfully conjugated bacteria, which will be expressing both resistance phenotypes. To further confirm successful conjugation, plasmid DNA from these colonies can be harvested and then a section of DNA specific to the transferred plasmid can be amplified using polymerase chain reaction, or PCR. When the PCR product is run on an electrophoresis gel alongside a ladder of standard sizes, a PCR fragment of a known size should be visible on the gel, further confirming successful conjugation. In this experiment, a plasmid will be used to transfer the ampicillin resistance gene via conjugation from a donor strain to a tetracycline-resistant recipient strain. After this, to confirm conjugation, the conjugation mixture will be incubated on a plate containing both antibiotics leaving only the transformed bacteria. Finally, successful conjugation will be further confirmed with PCR.

Before starting the procedure, put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves. Next, sterilize the workspace using 70% ethanol to wipe down the surface.

In this procedure, the ampicillin resistance gene will be transferred from the WM3064 strain of E. coli to the J53 strain of E. coli via conjugation. The donor strain WM3064 is resistant to tetracycline and ampicillin and it requires diaminopimelic acid, or DAP, to grow. The recipient strain J53 is only resistant to tetracycline and it does not require DAP to grow. This means that successfully conjugated cells should be resistant to tetracycline and ampicillin and can grow without DAP.

Prepare the donor strain culture by inoculating five milliliters of LB containing 0.3 millimoles of DAP with a scrap of the frozen donor strain glycerol stock. Then, prepare the recipient strain by inoculating five milliliters of LB broth without DAP with a scrap of the frozen recipient strain glycerol stock. Grow these cultures overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration and shaking at 220 RPM in a shaking incubator. Once the cultures have grown to an OD 600 of two, remove one milliliter of culture from each and place this into two new separate 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tubes. Then, centrifuge these aliquots at 3000 RPM for five minutes to pellet the bacterial cells. Discard the supernatant and wash each pellet with 250 microliters of 1X PBS. Centrifuge the samples again and, after discarding the supernatant, resuspend each pellet in 500 microliters of PBS.

To begin the conjugation procedure, first combine 50 microliters of recipient cells with 50 microliters of donor cells in a 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tube and mix by pipetting up and down gently. Next, pipette 100 microliters of the recipient cell culture onto another 1X tetracycline plate containing DAP. Next, prepare your negative control by pipetting 100 microliters of the recipient cell culture only onto a non-selective agar plate containing DAP. Then, incubate the conjugation and negative control plates overnight at 37 degrees Celsius.

The next day, take a sterile cell scraper and harvest cells from the conjugation plate by collecting colonies. Then, transfer the colonies to a sterile 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tube containing one milliliter of 1X PBS. Repeat this process to collect the recipient cells from the other plate.

After this, vortex the samples to mix. After mixing, transfer the tubes to a centrifuge to gently pellet the cells. Discard the supernatant, then wash the cell pellets in one milliliter of PBS and vortex the tubes to resuspend the cells. Pellet the cells again by centrifuging. Discard the supernatant again and resuspend both cell pellets in one milliliter of PBS. Now, using a sterile pipette tip, plate 100 microliters of the conjugation reaction cell mixture onto an LB agar plate without DAP containing 1X tetracycline and 1X ampicillin. Repeat the plating method using 100 microliters of a ten-fold dilution of the same cell mixture in PBS onto another LB agar plate without DAP containing 1X tetracycline and 1X ampicillin.

Finally, pipette 100 microliters of the negative control cell mixture onto a single LB agar plate with 1X tetracycline only. After overnight incubation at 37 degrees Celsius, the colonies should be visible. Using a sterile pipette tip, pick a single colony from the conjugation reaction plate and add it to a tube containing five milliliters of selective LB media containing both antibiotics. Then, repeat the colony isolation by selecting a single colony from the recipient cell plate. Grow these cultures overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration at 220 RPM.

The next day, wipe down the bench top with 70% ethanol and remove the plates from the incubator. Use a DNA mini prep kit to isolate DNA from 4. 5 milliliters of each culture according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After completing the DNA mini prep, elute the DNA using 35 microliters of nuclease-free water. Finally, use the remaining 0. 5 milliliters of each culture to prepare one milliliter glycerol stocks by adding 0.5 milliliters of 100% glycerol for a one-to-one dilution. Place these aliquots at minus 80 degrees Celsius for storage until needed.

To confirm successful conjugation by PCR, first prepare a PCR master mix by adding 75 microliters of 2X PCR master mix to a microcentrifuge tube. Then, add 7.5 microliters each of a 10 micromolar forward primer and a 10 micromolar reverse primer designed to amplify the ampicillin resistance gene from the plasmid. Next, prepare a second PCR master mix by adding 75 microliters of 2X PCR master mix to a microcentrifuge tube and then adding 7.5 microliters each of a 10 micromolar forward primer and 10 micromolar reverse primer designed to amplify a housekeeping gene, in this case DNA gyrase B.

Now, add 15 microliters of the first master mix to a PCR tube and then add 10 nanograms, approximately two microliters of the template experimental DNA to the same tube. Bring the reaction up to a final volume of 25 microliters with nuclease-free water. Repeat these steps to produce the remaining five reactions, so that the tubes contain the components shown here. Now, transfer these reactions to a thermocycler with the block pre-heated to 98 degrees Celsius and then initiate the program. After completion of the PCR, remove the tubes from the machine. Then, load two microliters of each reaction mixed with two microliters of loading dye and four microliters of a molecular weight marker into consecutive wells of a 1% agarose gel. Set the gel to run at 150 volts for 20 minutes. Finally, visualize the gel using a UV illuminator.

In this experiment, the successful transfer of the ampicillin resistance gene via conjugation was confirmed via PCR. Here, a roughly 500 base pair sized band should be observed in the well containing the conjugated DNA and ampicillin primers, well two in this example. A housekeeping gene, DNA gyrase B, was loaded into wells three and five with conjugated DNA and recipient cell DNA, respectively. Bands observed in these wells act as a positive control to ensure the DNA template was present and that PCR was successful. Bands should not be observed in the well containing the reaction for recipient cell DNA and the ampicillin primer pair, well four in this example, because the recipient cells are not ampicillin-resistant. Additionally, no bands should be observed in the reactions lacking template DNA, wells six and seven here. If these conditions are met, this will confirm the successful transfer of the ampicillin resistance gene, conferring ampicillin resistance from the WM3064 strain of E. coli to the J53 strain of E. coli.