ファージトランスダクション:アンピシリン耐性をドナーからレシピエント大腸菌に伝達する方法

English

소셜에 공유하기

개요

ソース: アレクサンダー S. ゴールド1, トーニャ M. コルピッツ1

1ボストン大学医学部微生物学科、国立新興感染症研究所、ボストン、マサチューセッツ州

トランスダクションは、バクテリオファージ(ファージ)を利用する細菌間の遺伝的交換の一形態であり、原核生物に排他的に感染するウイルスのクラスである。この形態のDNA移動は、ファージを通じてある細菌から別の細菌に移り、1951年にノートン・ジンダーとジョシュア・レデレルグによって発見された(1)。バクテリオファージは1915年に英国の細菌学者フレデリック・ツールトによって最初に発見され、その後1917年にフランス系カナダ人の微生物学者フェリックス・デレル(2)によって再び発見された。それ以来、これらのファージの構造と機能は広く特徴付けられており(3)、これらのファージを2つのクラスに分割する。これらのクラスの最初のクラスは、感染時に宿主細菌内で増殖し、細菌代謝を破壊し、細胞を溶解し、子孫ファージを放出する溶解ファージである(4)。この抗菌活性と抗生物質耐性細菌の有病率の増加の結果として、これらの溶解ファージは最近、抗生物質の代替治療として有用であることが証明された。これらのクラスの2番目は、溶解サイクルを介して宿主内で増殖するか、またはそのゲノムが宿主のゲノムが宿主のゲノムに統合される静止状態に入ることができるリソジェニックファージです(図1)。複数の後の世代(4)で誘発される生産。

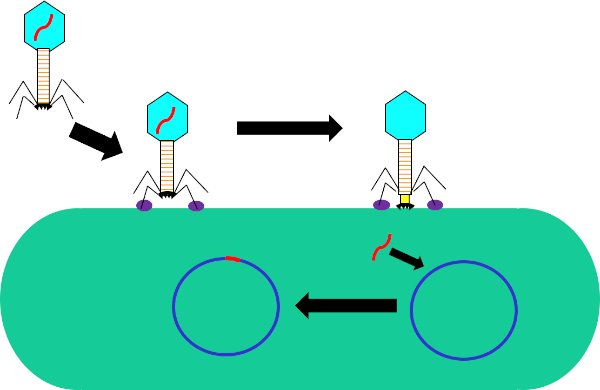

図1:バクテリオファージによる宿主細胞の感染尾線維と受容体(紫色)との相互作用を介して細菌細胞壁へのファージによる吸着。細胞表面に一度、ファージは収縮鞘(黄色)によって細胞壁に移動されるベースプレート(黒)を使用して細菌細胞に不可逆的に付着する。ファージゲノム(赤色)は、細胞に入り、宿主細胞ゲノムに統合する。

細菌の伝達は自然に起こるプロセスですが、現代の技術を使用して、実験室の設定で細菌に遺伝子を移用するために操作されています。ファージなどのリソジェニックファージのゲノムに目的の遺伝子を挿入することで、これらの遺伝子を細菌のゲノムに移し、その結果、これらの細胞内で発現することができます。形質転換などの他の遺伝子導入方法は、遺伝子の伝達および発現にプラスミドを使用するが、ファージゲノムをレシピエント細菌のそれに挿入することは、この細菌に新しい形質を与える可能性を有するだけでなく、自然に起こる突然変異および細胞環境の他の要因は、転移した遺伝子の機能を変化させる。

結合などの水平遺伝子導入の他の方法と比較して、トランスダクションはドナーおよびレシピエント細胞に必要な基準でかなり柔軟です。使用されているファージのゲノム内に収まる可能性のある任意の遺伝的要素は、ドナー細菌の任意の株から、両方がファージに寛容である限り、ドナー細菌の任意の株から、必要なファージ受容体の発現を必要とする。セル サーフェス。この遺伝子がドナーゲノムから移動し、ファージに包装されると、レシピエントに移すことができる。トランスダクションに続いて、目的の遺伝子を含むレシピエント細菌を選択する必要があります。これは、抗生物質耐性をコードする遺伝子の場合に、目的の遺伝子、または遺伝子の本質的な機能をマークするために、FLAGタグやポリヒスチジンタグなどの遺伝子マーカーを使用することによって行うことができます。さらに、PCRを使用して、トランスダクションの成功をさらに確認することができます。対象遺伝子内の領域にプライマーを使用し、シグナルを陽性対照と比較することにより、目的の遺伝子を有する細菌、および負の対照、ファージのない経度反応と同じステップを受けた細菌。細菌の伝達は分子生物学において有用なツールであるが、特に最近の抗生物質耐性の上昇に関して、細菌の進化において重要な役割を果たし続けている。

この実験では、細菌伝達を用いて、抗生物質アンピシリンに対する耐性をコードする遺伝子を、大腸菌のW3110株からP1バクテリオファージ(5)を介してJ53株に伝達した。この実験は、2つの主要なステップで構成されていました。まず、ドナー株からアンピシリン耐性遺伝子を含むP1ファージの調製。第2に、この遺伝子をP1ファージによるトランスダクションによりレシピエント株に転移させる(図1)。いったん実施すると、アンピシリン耐性遺伝子の正常な転写はqPCRによって決定され得る(図2)。経転移が成功した場合、大腸菌のJ53株はアンピシリンに対して耐性であり、この耐性を与える遺伝子はqPCRによって検出可能である。もし失敗した場合、アンピシリン耐性遺伝子の検出はなく、アンピシリンはJ53株に対する有効な抗生物質として機能し続けるであろう。

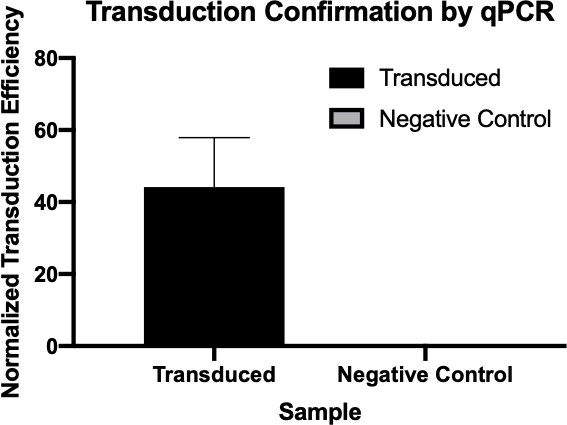

図2:qPCRによるトランスダクションの成功の確認トランスダクション反応と陰性対照反応から対象遺伝子に対して検出されたCq値を比較し、これらの値をハウスキーピング遺伝子に対して正規化することで、細菌の伝達が成功したことを確認することができました。

Procedure

Applications and Summary

The transfer of genes to and from bacteria by bacteriophage, while a natural process, has proved extremely useful for a multitude of research purposes. While other methods of gene transfer such as transformation and conjugation are possible, transduction uniquely uses bacteriophages; not only allowing for gene integration into the host genome, but also for gene delivery to multiple bacteria that are not susceptible to other methods. This process, while especially useful in the laboratory, has also been used in the recently emerging field of gene therapy, more specifically in alternative gene therapy, a therapeutic strategy that utilizes bacteria to deliver therapeutics to target tissues, many of which are not susceptible to other delivery methods and have much clinical relevance (8,9).

References

- Lederberg J, Lederberg E.M., Zinder, N.D., et al. Recombination analysis of bacterial heredity. Cold Spring Harbor symposia Quantitative Biol. 1951;16:413-43.

- Duckworth DH. "Who Discovered Bacteriophage?". Bacteriology Reviews. 1976;40:793-802.

- Yap ML, Rossman, M.G. Structure and Function of Bacteriophage T4. Future Microbiol. 2014;9:1319-27.

- Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze, Z., Morris, J. G. Bacteriophage Therapy Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2001;45(3):649-59.

- Moore S. Sauer:P1vir phage transduction 2010 [Available from: https://openwetware.org/wiki/Sauer:P1vir_phage_transduction].

- Kobayashi A, et al. Growth Phase-Dependent Expression of Drug Exporters in

- Escherichia coli and Its Contribution to Drug Tolerance. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188(16):5693-703.

- Rocha D, Santos, CS, Pacheco LG. Bacterial reference genes for gene expression studies by RT-qPCR: survey and analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2015;108:685-93.

- Pálffy R. et al. Bacteria in gene therapy: bactofection versus alternative gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2006 13:101-5.

- O'Neill JM, et al. Intestinal delivery of non-viral gene therapeutics: physiological barriers and preclinical models. Drug Discovery Today. 2011;16:203-2018.

내레이션 대본

Bacteria can adapt quickly to a fast-changing environment by exchanging genetic material and one way they can do this is via transduction, the exchange of genetic material mediated by bacterial viruses. A bacteriophage, often abbreviated to phage, is a type of virus that infects bacteria by first attaching to the surface of the host and then injecting its DNA into the bacterial cell. It then degrades the host cell’s own DNA and replicates its viral genome, whilst hijacking the cell’s machinery to synthesize many copies of its proteins. These phage proteins then self-assemble and package the phage genomes to form multiple progeny. However, due to the low fidelity of the DNA packaging mechanism, occasionally, the phage packages fragments of bacterial DNA into the phage capsid. After inducing the lysis of the host, the phage progeny are released and, once such a phage infects another host cell, it transfers the DNA fragment of its previous host. This can then recombine and become permanently incorporated into the new host’s chromosome, thereby mediating gene transfer between the two bacteria.

To carry out phage transduction in the laboratory requires a donor strain that contains a gene of interest, a recipient strain that lacks it, a phage that can infect both the strains, and a method to select the transduced bacteria. In most cases, this will be a selective solid growth media that supports the growth of transduced bacteria but inhibits the growth of non-transduced ones. To begin, the donor strain that contains the gene of interest is cultured in a liquid growth medium. When all the bacteria are actively dividing in the log phase of their growth, the culture is inoculated with the target phage. After three to four hours of incubation, when nearly all the bacteria have lysed and released the phage particles, the donor phage lysate is inoculated into a freshly grown culture of the recipient bacterial strain. After a brief incubation of one hour, the culture should now contain a mixture of transduced and non-transduced bacterial cells and this is screened for the transduced cells by spreading a fraction of the suspension onto an appropriate selective solid growth media. Upon further incubation, the transduced cells should grow and multiply to yield visible colonies. These colonies can then be selected for further analysis using a variety of methods to further confirm successful transduction, such as colony PCR, DNA sequencing, or quantitative PCR.

Before starting the procedure, put on any appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves. Next, sterilize the workspace with 70% ethanol and wipe down the surface.

After this, prepare three one-milliliter aliquots of LB salt solution. Now, prepare a donor strain culture by adding 100 microliters of E. coli to a 15 milliliter conical vial containing five milliliters of LB growth medium with 500 micrograms of ampicillin. Then, grow the culture overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration and shaking at 220 rpm. The next day, wipe down the bench top with 70% ethanol before removing the culture from the shaking incubator. Next, dilute the overnight culture one to 100 by adding 10 microliters of donor strain to 990 microliters of fresh LB supplemented with salt solution.

Allow the bacterial dilution to grow at 37 degrees Celsius for two hours with aeration and shaking at 220 rpm. Once the cells have reached early log phase, remove the culture from the incubator, add 40 microliters of P1 phage to the culture and incubate again. Continue to monitor the cells for one to three hours until the culture has lysed. Next, add 50 to 100 microliters of chloroform to the lysate and mix by vortexing. Then, centrifuge the lysate to remove debris and transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube. Add a few drops of chloroform to the supernatant and store it at four degrees Celsius for no more than one day.

To begin the transduction procedure, obtain a one milliliter culture of recipient strain. Next, transfer 100 microliters of donor phage lysate into a 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tube and incubate it at 37 degrees Celsius with the cap open for 30 minutes to allow any remaining chloroform to evaporate. While the donor phage lysate incubates, pellet the recipient strain cells via gentle centrifugation. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 300 microliters of fresh LB containing 100 millimolar magnesium sulfate and five millimolar calcium chloride.

Next, set up the transduction reaction by combining 100 microliters of the recipient strain and 100 microliters of the donor phage lysate in a microcentrifuge tube. Then, set up the negative control by combining 100 microliters of the recipient strain and 100 microliters of the LB with magnesium sulfate and calcium chloride. After incubation, add 200 microliters of one molar sodium citrate and one milliliter of LB to both tubes, and mix by gently pipetting up and down. Then, after the tubes have been incubated for an hour, gently pellet the cells via centrifugation.

After centrifuging, discard the supernatant and resuspend the pelleted cells in 100 microliters of LB with 100 millimolar sodium citrate. Vortex the solutions and pipette the entire transduced sample onto an LB agar plate with 1X ampicillin. Finally, pipette the entire volume of the negative control cell mixture onto an LB agar plate without ampicillin. After incubating the plates overnight at 37 degrees Celsius, use a sterile pipette tip to pick three to four colonies from the transduction plate and streak them onto a new LB agar plate containing 1X ampicillin and 100 microliters of one molar sodium citrate. Repeat this plating method for the negative control on another LB agar plate containing only 100 microliters of one molar sodium citrate. Then, incubate the plates at 37 degrees Celsius overnight to allow colonies free of phage to grow.

The next day, wipe down the bench top with 70% ethanol before removing your plates from the incubator. Using a sterile pipette tip, pick three colonies from the transduction plate and add them each to a separate tube containing five milliliters of LB media. Then, select three colonies from the negative control plate and add them to another tube containing five milliliters of LB media. Grow the cultures overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration and shaking at 220 rpm. After sterilizing the bench top as previously demonstrated, use a DNA miniprep kit to isolate DNA from 4.5 milliliters of each culture according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, elute the DNA with 35 microliters of nuclease-free water and measure the resulting concentration by lab spectrophotometer. Finally, prepare glycerol stocks by adding the remaining 0.5 milliliters of both bacterial solutions to 0.5 milliliters of 100% glycerol.

To confirm transduction, first prepare two qPCR master mixes for 24 qPCR reactions. For the first master mix, add 150 microliters of qPCR buffer mix to a microcentrifuge tube and 12 microliters each of a forward and reverse primer designed to amplify the ampicillin resistance gene. Next, prepare a second qPCR master mix by adding 150 microliters of qPCR master mix to a microcentrifuge tube and then adding 12 microliters each of a forward primer and reverse primer designed to amplify a housekeeping gene.

For each qPCR reaction, combine 100 micrograms of experimental DNA from each reaction with 14.5 microliters of qPCR master mix. Now, prepare the remaining reactions as previously demonstrated. Transfer the reactions to a thermocycler preheated to 94 degrees Celsius and then initiate the program. Finally, use the cycle quantification, or Cq, values generated by qPCR to calculate the normalized transduction efficiency of the ampicillin resistance gene.

The cycle quantitation, or Cq, values for the genes of interest were tabulated for each of the negative controls and transduced samples. Low Cq values, typically below 29 cycles, like the transduced samples in this example indicate high amounts of the target sequence.

A housekeeping gene, also tabulated here, is used as a loading control to normalize the amount of DNA in each reaction and as a positive control to ensure the qPCR is working. Provided the same amounts of the housekeeping gene are loaded, it is found at relatively the same rate in each sample.

Next, to calculate the delta Cq value for each sample, subtract the Cq value of the housekeeping gene for each sample from the Cq value of its corresponding target gene. For example, the delta Cq of the first negative control is 13.54. Then, use this value to calculate the normalized transduction efficiency of each sample using the formula shown here. Finally, the average normalized transduction efficiency for each sample group can be calculated.