마이크로 웨이브 조사를 사용하여 잠재적 인 기생충 치료제로 백본 순환 펩타이드 라이브러리 개발

Summary

A simple and general method for the synthesis of cyclic peptides using microwave irradiation is outlined. This procedure enables the synthesis of backbone cyclic peptides with a collection of different conformations while retaining the side chains and the pharmacophoric moieties., and therefore, allows to screen for the bioactive conformation.

Abstract

단백질 – 단백질 상호 작용 (프로톤 펌프 억제제)는 거의 모든 생물학적 과정에 밀접하게 관여하고 많은 인간의 질병에 연결됩니다. 따라서, 기초 연구 및 제약 산업에서 프로톤 펌프 억제제를 대상으로 주요 노력이있다. 단백질 – 단백질 인터페이스 플랫 보통 대형이고, 종종 표적 부위 작은 분자의 발견을 복잡 포켓이 부족하다. 항체를 사용하여 대체 타겟팅 방식은 가난한 경구 생체 이용률, 낮은 세포 투과성 및 생산의 비 효율성으로 인해 제한이 있습니다.

PPI 인터페이스를 타겟팅 펩타이드를 사용하는 것은 몇 가지 장점을 갖는다. 펩티드는 높은 구조적 유연성 증가 선택성을 가지며, 일반적으로 저렴하다. 그러나, 펩티드는 가난한 안정성과 효율성 건너 세포막을 포함하여 자신의 한계를 가지고있다. 이러한 한계를 극복하기 위해, 펩티드 고리 화 반응이 수행 될 수있다. 환화 펩티드 선택성을 향상시키기 위해 설명되었다, 대사 안정성 및 생체 이용율. 그러나, 고리 형 펩티드의 생체 활성 입체 형태를 예측하는 것은 단순하지 않다. 이 문제를 극복하기 위해, 하나의 매력적인 접근 모든 백본 순환 펩티드가 동일한 기본 순서를 가지고 있지만, 이러한 링 크기와 위치 등 자신의 형태에 영향을 미치는 매개 변수에 차이가있는 화면에 초점을 맞춘 라이브러리를 화면으로 이동합니다.

우리는 특정 기생충 프로톤 펌프 억제제를 표적 백본 환상 펩티드 라이브러리를 합성하는 상세한 프로토콜을 설명한다. 합리적인 설계 방식을 사용하여, 우리는 활성화 된 C-키나제 (LACK)의 골격 단백질 패 eishmania 수용체에서 유래 펩티드를 개발했다. 우리는하지만 포유류의 호스트 상 동체에, 기생충에 보존되어 부족 시퀀스, 기생충 '생존에 중요한 단백질 상호 작용 사이트를 나타낼 수 있다는 가설을 세웠다. 환형 펩티드는 반응 시간을 감소시키고 증가시키는 마이크로파 조사를 이용하여 합성했다능률. 다른 크기의 환 골격 환상 펩티드 라이브러리를 개발하는 것은 대부분의 생물학적 활성에 대한 체계적인 형태 화면을 용이하게한다. 이 방법은 고리 형 펩티드를 합성, 일반 신속하고 용이 한 방법을 제공한다.

Introduction

단백질 – 단백질 상호 작용 (프로톤 펌프 억제제)는 세포 내 신호 전달에서 세포사 1, 가장 생물학적 과정에서 중요한 역할을한다. 따라서, 프로톤 펌프 억제제를 대상으로하는 기초 연구 및 치료 응용 프로그램에 대한 기본적인 중요하다. 프로톤 펌프 억제제는 구체적이고 안정적인 항체에 의해 규제하지만, 항체 제조 및 가난한 생체 이용률을 가지고 비싸고 어려운 할 수 있습니다. 또한, 프로톤 펌프 억제제는 작은 분자의 대상이 될 수있다. 소분자는 항체에 비해 합성 쉽고 저렴; 그러나, 이들은 상대적으로 유연성이 큰 단백질 – 단백질 인터페이스 2,3-보다 작은 공동에 잘 맞게. 다양한 연구는 간단하고 저렴 항체보다 작은 분자보다 더 유연 펩타이드, 단백질 인터페이스를 결합하고 프로톤 펌프 억제제 4,5 조절할 수 있음을 증명하고있다. 글로벌 치료 펩타이드 시장은 2013 년 백오십억 달러의 주위에 평가하고, 10.5 %의 annua 성장하고있다에서야 6. 또한, 50 개 이상의 판매 펩티드, 임상 시험의 다른 단계에서 약 270 펩티드, 고급 전임상 단계 7에서 약 400 펩티드가있다. 많은 펩타이드 약물로 사용되고 있지만, 펩티드가 여전히 불량한 생체 이용률 및 안정성 횡단 세포막에서 비효율과 구조적 유연성 8,9 포함한 광범위한 적용을 제한 여러 과제를 제기. 이러한 단점을 극복하기위한 하나의 대안은 로컬 (D- 아미노산 및 N- 알킬화) 및 글로벌 (고리) 제약 8,10-12로 다른 수정 사항을 적용하는 것입니다. 이러한 수정은 자연적으로 발생합니다. 예를 들어, 시클로 스포린 A는 면역 억제제 환상 천연 펩티드는 단일 D- 아미노산을 포함하고, N-알킬화 변형 13,14 겪는다.

천연 아미노산의 변형은 종종 영향을 펩티드, 예컨대 D- 및 N- 알킬화 같은 로컬 제약을 유도9;의 생물학적 활성. 그러나, 관심있는 서열이 동일하게 유지 될 수있는 고리 화 반응은 생물학적 활성을 유지하기 쉽다. 환화 다른 배좌 사이의 평형을 줄여 펩타이드 구조적 공간을 제한하는 매우 매력적인 방법이다. 그것은 일반적으로 하나의 기능을 매개 활성 형태에 펩타이드를 제한하여 생물학적 활성과 선택도를 증가시킨다. 환화는 덜 분해 효소에 의해 인식되는 펩티드의 형태를 유지함으로써 펩티드의 안정성을 향상시킨다. 실제로, 순환 펩티드들은 선형 대응 15 ~ 17에 비해 대사 안정성, 생체 이용률 및 선택성을 향상 것으로 나타났다.

그러나, 고리는 경우에 따라 제한을 달성 생체 활성 형태로 펩티드를 방지 할 수 있기 때문에 양날의 검이 될 수있다. 이 장애물을 극복하기 위해 초점을 맞춘 도서관은 모든 펩티드는 동일한 기본 sequenc이즉 결과적으로 일정한 약물 조제를 합성 할 수있다. 펩티드 라이브러리의 순서이어서 대부분 생리 활성 형태 9,18 스크리닝하는 이러한 링의 크기와 위치로서 그 구조에 영향을 미치는 매개 변수에서 다르다.

펩티드 용액 이제 더 널리 펩티드 합성 방법이며 더 논의 될 것이다 고상 펩티드 합성 (SPPS) 접근법에 의해 양으로 합성 할 수있다. SPPS 화학적 변형은 화합물의 합성 (19)의 넓은 범위를 준비하는 링커를 통해 고체 지지체에 의해 수행되는 프로세스이다. SPPS는 N 말단에, 고체 지지체에 부착 된 C 말단으로부터 단계적으로 아미노산의 연속 펩티드 결합에 의해 조립을 가능하게한다. N-α 아미노산 측쇄는 세인트 당 하나의 아미노산의 첨가를 위해 펩타이드 신장 동안 사용 된 반응 조건에 안정한 보호기로 마스킹되어야EP. 마지막 단계에서, 펩티드는 수지로부터 방출되고 보호기 측쇄는 병용 제거된다. 펩타이드를 합성하는 동안, 모든 수용성 시약을 여과에 의해 펩티드 – 고체 지지체 매트릭스로부터 제거하고 각각의 커플 링 단계의 끝에서 씻겨 수있다. 이러한 방식으로, 높은 농도에서 시약의 과량 완료 커플 링 반응을 구동 할 수 있으며 모든 합성 단계는 재료 (20)의 임의의 이동없이 동일한 용기 내에서 수행 될 수있다.

SPPS은 반응 21 모니터링 불완전 반응, 부반응, 불순한 시약뿐만 아니라 문제의 생산과 같은 어떤 한계가 있지만, SPPS의 장점은 펩티드 합성 "금 표준"만들었다. 이러한 장점에 기인하는 비 천연 아미노산, 자동화, 간편한 정제를 통합하는 옵션, 물리적 손실을 최소화하고, 과량의 시약의 사용을 포함높은 수율. SPPS는 곤란 서열 21, 22, 23의 형광 변형, 펩타이드 라이브러리 (24, 25)의 합성에 매우 유용한 것으로 밝혀졌다. SPPS 또한 올리고 뉴클레오티드 (26, 27), 올리고당 28, 29, 펩티드 핵산 (30, 31)와 같은 다른 폴리 체인 어셈블리를위한 매우 유용합니다. 흥미롭게도, 어떤 경우에는, SPPS 전통적 용액 32,33에서 만들어진 작은 분자를 합성하기위한 유리한 것으로 나타났다. SPPS 업계 36-38에서 연구 및 교육 (34, 35)에 대한 소규모뿐만 아니라 대규모에 모두 사용된다.

주로 펩티드 합성 SPPS 방법에 사용되는 두 개의 합성 전략 옥시 카르 보닐 (BOC) 9- 플루 오레 닐메 톡시 카보 닐 (Fmoc)이다. SPPS 도입 원래 전략은 R로부터 펩티드 보호기 측쇄를 제거하고 절단하는 강산성 조건이 필요 BOC이었다esin. FMOC 계 펩티드 합성은, 그러나, 적당한 염기 조건을 이용하고, 산 – 불안정성 BOC 프로토콜 39에 경한 대안이다. 및 Fmoc 전략은 산성 조건 하에서 수지로부터 펩티드를 절단하면서 합성의 마지막 단계에서 제거된다 직교 t- 부틸 (tBu 중에서) 측쇄 보호를 이용한다.

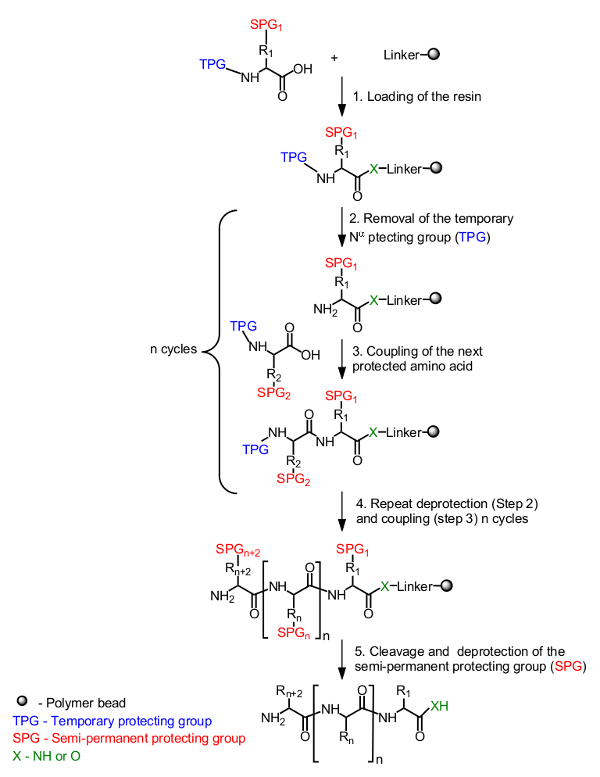

고체 지지체상의 펩티드 합성을위한 일반적인 원리는도 1에 제시된다. N-α 말단의 임시 보호기에 의해 마스크 초기 아미노산은 C- 말단에서 수지 상에 로딩된다. (도 1, 단계 1) 필요에 따라 측쇄를 마스크하기 반영구 보호기 또한 사용된다. 대상 펩티드의 합성 N-α-임시 보호기의 탈 보호의 반복적 인 사이클의 다음 보호 된 아미노산 (도 1, 단계 2) 및 커플 링 (도 1의 N 말단에 C 말단으로부터 조립 </str 옹> 단계 3). 마지막 아미노산 (도 1, 단계 4)을로드 한 후, 펩티드를 수지 지지체로부터 절단하고 반영구 보호기는 (도 1, 단계 5)을 제거한다.

고상 펩티드 합성의도 1은 일반적인 방식. N-α 보호 된 아미노산은 수지 (단계 1)에 링커를 통해 카르복실기를 사용하여 고정된다. 바람직한 펩티드는 N-α (단계 2) 및 아미노산 커플 링 (단계 3)로부터의 임시 보호기 (TPG)의 탈 보호의 반복 사이클에 의해 N 말단에 C 말단에서 선형 방식으로 조립된다. 합성 (공정 4)를 달성 한 후에, 반영구 보호기 (SPG)를 펩티드의 절단 (단계 5) 중 탈 보호된다.= "_ 빈"을 얻을>이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

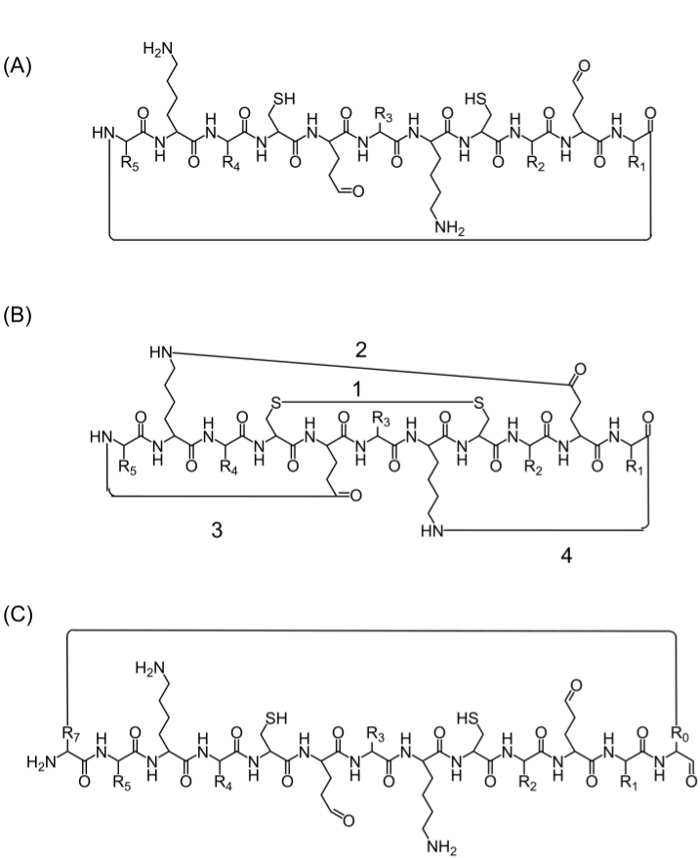

이 환화 (도 2A)에 대한 하나의 옵션, (B) 고리를 제공하기 때문에이 편리한 방법이지만 한정 – (A) 머리 – 꼬리 환화는 : 완전한 펩티드 사슬의 조립 후, 환화는 몇 가지 대안에 의해 달성 될 수있다 생활 성 관능기를 함유 관심 서열에서 아미노산을 사용하여 – 그러나, 이들 아미노산의 사용을 방해하지 않고 아미노산 (또는 다른 빌딩 블록)을 첨가하여 생물학적 활성 (도 2B), 및 (C) 고리 화에 영향을 미칠 수있다 생리 활성 순서. 그것이 관심 서열 (도 2C)를 수정하지 않고 집중 라이브러리의 제조를 허용하는 이들 분자를 도입하여 광범위하다.

에프2. 대안 igure 펩티드 고리 화 전략 C- 말단 및 N- 말단 사이의 펩티드 결합을 통해 꼬리 환화에 (A) 헤드.; 관능기 사이의 (B) 고리 등 / 글루탐산 (2), 또는 측쇄을 N- 또는 C- 말단 (3 아스파르트하는 시스테인 잔기 (1), 또는 라이신 측쇄 사이의 아미드 결합 사이의 이황화 결합로서 -4); (R0) 전 (R7) 생리 활성 순서 후에 예를 들어, 여분의 아미노산 또는 아미노산 유도체 또는 작은 분자를 추가하여 (C) 고리 화. 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

따라서 마이크로파를 이용한 유기 화학 촉진, 합성 반응을 가열하는 마이크로파 조사 사용은 40, 41을 변형. 마이크로파 화학은 흡수 용매 시약 능력 /에 기초전자 레인지 에너지 변환 (42)를 가열한다. 기술이 널리되기 전에, 주요 단점은, 제어 및 합성 프로토콜의 재현성과 충분한 온도 및 압력 제어 시스템 (43, 44)로 사용할 수의 부족을 포함 극복되어야했다. 마이크로파를 이용한 펩티드 합성의 첫 번째보고는 커플 링 효율 및 순도 (45)의 현저한 개선과 함께 여러 짧은 펩티드를 합성 주방 마이크로파 (7-10 아미노산)를 사용하여 수행 하였다. 또한, 마이크로파 에너지는, 연쇄 응집을 감소 부반응을 감소, 라세 미화를 제한하고, 모든 어렵고 긴 시퀀스 46에서 53 사이에 중요한 결합 율을 개선하기 위해 도시 하였다.

현재 고체 지지체상의 펩티드 또는 관련 화합물의 합성을위한 마이크로파 조사를 사용하는 유기 용매 (54)의 대신에 물 (A)의 합성을 포함하여 광범위하다; (B)의 합성 펩티드와이러한 합성에 의한 입체 장애 아미노산 유도체의 낮은 커플 링 효율로 일반적으로 곤란 또는 포스 포 글리코 펩티드 55-58 59-61, 일반적인 번역 후 변형; (C) 그 측쇄에 연결되어 질소 원자 (62), 또는 펩 토이 드와 아미노산 잔기의 C (α)의 대체에 의해 형성 될 수 azapeptides 같은 백본 변형 펩타이드의 합성 오히려 Cα 원자 63, 64보다 아미드 질소; (D) 순환 펩티드 65-71을 합성; 조합 라이브러리 51,72의 및 (E) 합성. 수많은 경우에서, 저자는 높은 효율을 종래보고 된 프로토콜에 비하여 마이크로파를 이용하는 제조 시간을 감소시켰다.

합리적인 디자인 73-75을 사용하여, 우리는 fo를 발판 패 eishmania의 수용체에서 파생 된 구충제 펩티드 개발R은 C-키나제 (부족) 활성화. 부족 슈만 편모충 감염 (76)의 초기 단계에서 중요한 역할을한다. 부족 낮은 수준을 표현하는 기생충이 부족하니이 필수 기생충 신호 프로세스와 단백질 합성 (78)에 관여으로도 면역 손상 쥐에게 77 기생하지 못한다. 따라서 부족은 키 비계 단백질 79 귀중한 약물 표적입니다. 하지만 호스트 포유류의 동체 랙에, 기생충에 보존되어 부족 시퀀스를 중심으로, 우리는 8 아미노산 펩타이드 문화 슈만 편모충 SP. 가능성을 감소 (RNGQCQRK)를 확인했다.

여기서는 상술 LACK 단백질 서열로부터 유래 된 골격 환상 펩티드 합성을위한 프로토콜을 기술한다. 펩티드의 Fmoc / tBu 중에서 프로토콜 SPPS 방법론에 의해 마이크로 웨이브 가열을 사용하여 고체 지지체 상에 합성했다. 펩티드는 아미드 결합 등을 통해 TAT 47-57 (YGRKKRRQRRR) 담체 펩티드에 접합 된SPPS의 일부입니다. 세포 내로화물의 다양한 TAT 기반 전송은 15 년 이상 사용되어왔다 및 세포 내 소기관으로 전달화물 80을 확인 하였다. 네 개의 다른 링커, 숙신산 및 글루 타르 산 무수물뿐만 아니라 디프 및 피 멜산는 4시 58분 탄소수 카르복시산 링커를 생성하는 고리 화 반응을 수행하는 데 사용 하였다. 고리 화 반응은 마이크로파 에너지를 사용하여 수행하고, 최종 절단 및 측쇄 탈 보호 단계는 마이크로파 에너지없이 수동으로 수행되었다. 자동화 된 마이크로파 합성기를 사용하면, 제품 순도를 향상 생성물 수율을 증가하고, 합성의 지속 기간을 감소시켰다. 이러한 일반적인 프로토콜은 시험 관내 및 생체 내에서 중요한 분자 메커니즘을 이해하고 상기 인간의 질병에 대한 잠재적 인 약물을 개발하는 펩티드를 이용하는 다른 연구에 적용될 수있다.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

완전 자동화 된 마이크로파 합성기를 사용하여 리 슈만 편모충 기생충의 부족 단백질로부터 유도 된 펩티드의 고리 골격 집중 라이브러리의 합성을 설명한다. 순환 펩티드의 초점을 맞춘 도서관은 보존 약물 조제와 다양한 링커로 개발되었다. 예컨대 글루 타르 산 무수물, 숙신산 무수물, 아 디프 산, 피 멜산, 리신, 오르니 틴, 및 다른 빌딩 블록과 같은 다양한 링커 첨가 환상 펩티드의 형?…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

우리는 도움이 토론 로렌 반 Wassenhove, Sunhee 황, 그리고 다리아 Mochly-로젠 감사합니다. 출자자는 연구 설계, 자료 수집 및 분석, 게시하는 결정, 또는 원고의 준비를 전혀 역할을 없었다 NQ하는 작업은 건강 그랜트 NIH RC4 TW008781-01 C-IDEA (SPARK)의 국립 연구소에 의해 지원되었다.

Materials

| REAGENTS | |||

| Solid support, Rink Amide AM resin ML | CBL | BR-1330 | loading: 0.49 mmol/g |

| Fmoc-Ala-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FA2100 | |

| Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FR2136 | |

| Fmoc-Asn(Trt)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FN2152 | |

| Fmoc-Asp(OBut)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FD2192 | |

| Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FC2214 | |

| Fmoc-Gln(Trt)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FQ2251 | |

| Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FE2237 | |

| Fmoc-Gly-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FG2275 | |

| Fmoc-His(Trt)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FH2316 | |

| Fmoc-Ile-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FI2326 | |

| Fmoc-Leu-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FL2350 | |

| Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FK2390 | |

| Fmoc-Met-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FM2400 | |

| Fmoc-Phe-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FF2425 | |

| Fmoc-Pro-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FP2450 | |

| Fmoc-Ser-(tBu)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FS2476 | |

| Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FT2518 | |

| Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FW2527 | |

| Fmoc-Tyr(But)-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FY2563 | |

| Fmoc-Val-OH | Advanced Chemtech | FV2575 | |

| 1-Methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP) | Sigma | 328634 | Caution Toxic/Highly flammable/Irritant. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Alfa Aesar | 43465 | Caution Toxic |

| Use high quality DMF to eliminate side reactions such as Fmoc removal as a result of the dimethylamine traces from DMF decomposition. | |||

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Sigma | D65100 | Caution Harmful |

| Dibromomethane (DBM) | Sigma | D41868 | Caution Harmful |

| Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) | Sigma | T62200 | Caution Corrosive/Toxic |

| Trifluoroacetic acid, HPLC grade (TFA) | Sigma | 91707 | Caution Corrosive/Toxic |

| Diethylether | Sigma | 31690 | Caution Highly flammable/Harmful |

| Triisopropylsilane (TIS) | Sigma | 233781 | Caution Irritant/Flammable |

| Water, HPLC grade | Sigma | 270733 | |

| Acetonitroile, HPLC grade (ACN) | Fisher Scientific | A998-4 | Caution Flammable/Irritant/Harmful |

| N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) | Sigma | 3440 | Caution Corrosive/Highly flammable |

| Piperidine | Sigma | W290807 | Caution Toxic/Highly flammable |

| Pyridine | Sigma | 270970 | Caution Highly flammable/Harmful |

| Ethanol (EtOH) | Sigma | 459844 | Caution Highly flammable/Irritant |

| 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt) | Sigma | 157260 | Caution Highly flammable/Irritant/Harmful |

| O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) | Sigma | 12804 | Caution Irritant/Harmful |

| Benzotriazole-1-ly-oxy-tris-pyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorphosphate (PyBOP) | Advanced Chemtech | RC8602 | Caution Irritant |

| Ninhydrin | Sigma | 454044 | Caution Harmful |

| Phenol | Sigma | P3653 | Caution Corrosive/Toxic |

| Potassium cyanide (KCN) | Sigma | 11813 | Caution Very Toxic |

| Potassium hydroxide (KOH) | Sigma | 221473 | Caution Toxic |

| N,N’- | Sigma | 38370 | Caution Flammable/ Toxic |

| Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) | |||

| 4-Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) | Sigma | 522805 | Caution Toxic/Irritant |

| Glutaric anhydride | Sigma | G3806 | Caution Flammable/Irritant/Harmful |

| Succinic anhydride | Sigma | 239690 | Caution Irritant/Harmful |

| Adipic acid | Sigma | A26357 | Caution Toxic/Irritant |

| Pimelic acid | Sigma | P45001 | Caution Toxic/Irritant |

| Chloranil | Sigma | 23290 | Caution Toxic/Irritant |

| Acetaldehyde | Sigma | 402788 | Caution Flammable/ Toxic |

| EQUIPMENT | |||

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Centrifuge | Beckman Coulter | Allegra 6R centrifuge | |

| Lyophilizer | Labconco | freezone 4.5 | |

| Vacuum pump | Franklin Electric | model 1101101416 with 3/4 HP | Alcatel pump with Franklin Motor |

| Polypropylene cartridge 12 ml | Applied Separation | 2419 | |

| Cap plug for 12 ml polypropylene cartridge | Applied Separation | 8157 | |

| Polypropylene cartridge 3 ml | Applied Separation | 2413 | |

| Cap plug for 3 ml polypropylene cartridge | Applied Separation | 8054 | |

| Stop cocks PTFE | Applied Separation | 2406 | |

| Tubes flat, 50 ml | VWR | 21008-240 | |

| Extraction manifold, 20 pos, 16 x 100 mm tubes | Waters | WAT200609 | |

| Shaker, BD adams™ nutator mixer | Fisher scientific | 22363152 | |

| Nalgene HDPE narrow mouth IP2 bottles, 125 ml | Fisher scientific | 03-312-8 | |

| Erlenmeyer flask | Fisher Scientific | FB-501, 500 ml | |

| Heating block | Thermolyne | 1760 dri bath | |

| Disposable borosilicate glass tubes with plain end | Fisher Scientific | 14-961-25 | |

| Micropipettes and tips Finnpipette | Thermo | 20–200 and 100–1,000 μl | |

| HPLC vials – micro vl pp 400 µl PK100 | VWR | 69400-124 | |

| HPLC vial- Blue Snap-It Cap | VWR | 66030-600 | |

| Analytical HPLC column | Peeke Scientific | U1-5C18Q-JJ | ultro 120 5 µm C18Q, 4.6 mm ID 150 mm |

| Prep HPLC column, XBridge | Waters | OBD C18 5 µm column | 19 mm × 150 mm |

| Mass spectrometer | Applied Biosystems | Voyager DE-RP |

Referências

- Wells, J. A., McClendon, C. L. Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein-protein interfaces. Nature. 450 (7172), 1001-1009 (2007).

- Arkin, M. R., Wells, J. A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing towards the dream. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (4), 301-317 (2004).

- Mandell, D. J., Kortemme, T. Computer-aided design of functional protein interactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5 (11), 797-807 (2009).

- Friedler, A., et al. Backbone cyclic peptide, which mimics the nuclear localization signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein, inhibits nuclear import and virus production in nondividing cells. Bioquímica. 37 (16), 5616-5622 (1998).

- Brandman, R., Disatnik, M. H., Churchill, E., Mochly-Rosen, D. Peptides derived from the C2 domain of protein kinase C epsilon (epsilon PKC) modulate epsilon PKC activity and identify potential protein-protein interaction surfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 282 (6), 4113-4123 (2007).

- Vlieghe, P., Lisowski, V., Martinez, J., Khrestchatisky, M. Synthetic therapeutic peptides: science and market. Drug discov today. 15 (1-2), 40-56 (2010).

- Marx, V. Watching Peptide Drugs Grow Up. Chemical & Engineering News. 83, 17-24 (2005).

- Denicourt, C., Dowdy, S. F. Medicine. Targeting apoptotic pathways in cancer cells. Science. 305 (5689), 1411-1413 (2004).

- Qvit, N., et al. Synthesis of a novel macrocyclic library: discovery of an IGF-1R inhibitor. J Comb Chem. 10 (2), 256-266 (2008).

- Patch, J. A., Barron, A. E. Mimicry of bioactive peptides via non-natural, sequence-specific peptidomimetic oligomers. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 6 (6), 872-877 (2002).

- Kessler, H. Peptide Conformations .19. Conformation and Biological-Activity of Cyclic-Peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 21 (7), 512-523 (1982).

- Gazal, S., Gelerman, G., Gilon, C. Novel Gly building units for backbone cyclization: synthesis and incorporation into model peptides. Peptides. 24 (12), 1847-1852 (2003).

- Fesik, S. W., et al. NMR studies of [U-13C]cyclosporin A bound to cyclophilin: bound conformation and portions of cyclosporin involved in binding. Bioquímica. 30 (26), 6574-6583 (1991).

- Kornfeld, O. S., et al. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species at the Heart of the Matter: New Therapeutic Approaches for Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 116 (11), 1783-1799 (2015).

- Boguslavsky, V., Hruby, V. J., O’Brien, D. F., Misicka, A., Lipkowski, A. W. Effect of peptide conformation on membrane permeability. J. Pept. Res. 61 (6), 287-297 (2003).

- Eguchi, M., et al. Solid-phase synthesis and structural analysis of bicyclic beta-turn mimetics incorporating functionality at the i to i+3 positions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 (51), 12204-12205 (1999).

- Altstein, M., et al. Backbone cyclic peptide antagonists, derived from the insect pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide, inhibit sex pheromone biosynthesis in moths. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (25), 17573-17579 (1999).

- Cheng, M. F., Fang, J. M. Liquid-phase combinatorial synthesis of 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-diones as the candidates of endothelin receptor antagonism. J. Comb. Chem. 6 (1), 99-104 (2004).

- Merrifield, R. B. Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis I. the Synthesis of a Tetrapeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 2149-2154 (1963).

- Pfeiffer, C. T., Schafmeister, C. E. Solid phase synthesis of a functionalized bis-peptide using ‘safety catch’ methodology. J Vis Exp. (63), e4112 (2012).

- Coin, I., Beyermann, M., Bienert, M. Solid-phase peptide synthesis: from standard procedures to the synthesis of difficult sequences. Nat. Protoc. 2 (12), 3247-3256 (2007).

- Qvit, N., et al. Design and synthesis of backbone cyclic phosphorylated peptides: the IκB model. Biopolymers. 91 (2), 157-168 (2009).

- Sainlos, M., Imperiali, B. Tools for investigating peptide-protein interactions: peptide incorporation of environment-sensitive fluorophores through SPPS-based ‘building block’ approach. Nat. Protoc. 2 (12), 3210-3218 (2007).

- Hilpert, K., Winkler, D. F., Hancock, R. E. Peptide arrays on cellulose support: SPOT synthesis, a time and cost efficient method for synthesis of large numbers of peptides in a parallel and addressable fashion. Nat. Protoc. 2 (6), 1333-1349 (2007).

- Qi, X., Qvit, N., Su, Y. C., Mochly-Rosen, D. A novel Drp1 inhibitor diminishes aberrant mitochondrial fission and neurotoxicity. J. Cell Sci. 126 (Pt 3), 789-802 (2013).

- Beaucage, S. L. Solid-phase synthesis of siRNA oligonucleotides. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 11 (2), 203-216 (2008).

- Dhanawat, M., Shrivastava, S. K. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Oligosaccharide Drugs: A Review. Mini Rev Med Chem. 9 (2), 169-185 (2009).

- Seeberger, P. H., Werz, D. B. Synthesis and medical applications of oligosaccharides. Nature. 446 (7139), 1046-1051 (2007).

- Plante, O. J., Palmacci, E. R., Seeberger, P. H. Automated solid-phase synthesis of oligosaccharides. Science. 291 (5508), 1523-1527 (2001).

- Komiyama, M., Aiba, Y., Ishizuka, T., Sumaoka, J. Solid-phase synthesis of pseudo-complementary peptide nucleic acids. Nat. Protoc. 3 (4), 646-654 (2008).

- Christensen, L., et al. Solid-Phase synthesis of peptide nucleic acids. J. Pept. Sci. 1 (3), 175-183 (1995).

- Qvit, N., et al. Development of bifunctional photoactivatable benzophenone probes and their application to glycoside substrates. Biopolymers. 90 (4), 526-536 (2008).

- O’Neill, J. C., Blackwell, H. E. Solid-phase and microwave-assisted syntheses of 2,5-diketopiperazines: small molecules with great potential. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 10 (10), 857-876 (2007).

- Qvit, N., Barda, Y., Shalev, D., Gilon, C. A Laboratory Preparation of Aspartame Analogs Using Simultaneous Multiple Parallel Synthesis Methodology. J. Chem. Educ. 84 (12), 1988-1991 (2007).

- Truran, G. A., Aiken, K. S., Fleming, T. R., Webb, P. J., Markgraf, J. H. Solid phase organic synthesis and combinatorial chemistry: A laboratory preparation of oligopeptides. J. Chem. Educ. 79 (1), 85-86 (2002).

- Verlander, M. Industrial applications of solid-phase peptide synthesis – A status report. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 13 (1-2), 75-82 (2007).

- Bray, B. L. Large-scale manufacture of peptide therapeutics by chemical synthesis. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2 (7), 587-593 (2003).

- Qvit, N. Development and therapeutic applications of oligonucleotides and peptides. chimica Oggi / CHEMISTRY today. 29 (2), 4-7 (2011).

- Carpino, L. A., Han, G. Y. 9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl Amino-Protecting Group. J. Org. Chem. 37 (22), 3404-3409 (1972).

- Gedye, R., et al. The use of microwave ovens for rapid organic synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (3), 279-282 (1986).

- Giguere, R. J., Bray, T. L., Duncan, S. M., Majetich, G. Application of commercial microwave ovens to organic synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (41), 4945-4948 (1986).

- Kappe, C. O., Dallinger, D. The impact of microwave synthesis on drug discovery. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 5 (1), 51-63 (2006).

- Kappe, C. O. Controlled microwave heating in modern organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 43 (46), 6250-6284 (2004).

- de la Hoz, A., Diaz-Ortiz, A., Moreno, A. Microwaves in organic synthesis. Thermal and non-thermal microwave effects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 34 (2), 164-178 (2005).

- Yu, H. M., Chen, S. T., Wang, K. T. Enhanced coupling efficiency in solid-phase peptide synthesis by microwave irradiation. J. Org. Chem. 57 (18), 4781-4784 (1992).

- Mingos, D. M. P., Baghurst, D. R. Tilden Lecture. Applications of microwave dielectric heating effects to synthetic problems in chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 20 (1), 1-47 (1991).

- Gabriel, C., Gabriel, S., Grant, E. H., Halstead, B. S. J., Mingos, D. M. P. Dielectric parameters relevant to microwave dielectric heating. Chem. Soc. Rev. 27 (3), 213-224 (1998).

- Sabatino, G., Papini, A. M. Advances in automatic, manual and microwave-assisted solid-phase peptide synthesis. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 11 (6), 762-770 (2008).

- Banerjee, J., Hanson, A. J., Muhonen, W. W., Shabb, J. B., Mallik, S. Microwave-assisted synthesis of triple-helical, collagen-mimetic lipopeptides. Nat. Protoc. 5 (1), 39-50 (2010).

- Bacsa, B., Kappe, C. O. Rapid solid-phase synthesis of a calmodulin-binding peptide using controlled microwave irradiation. Nat. Protoc. 2 (9), 2222-2227 (2007).

- Murray, J. K., Gellman, S. H. Parallel synthesis of peptide libraries using microwave irradiation. Nat. Protoc. 2 (3), 624-631 (2007).

- Palasek, S. A., Cox, Z. J., Collins, J. M. Limiting racemization and aspartimide formation in microwave-enhanced Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis. J Pept Sci. 13 (3), 143-148 (2007).

- Murray, J. K., Aral, J., Miranda, L. P. Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis Using Microwave Irradiation. Methods Mol. Biol. 716, 73-88 (2011).

- Galanis, A. S., Albericio, F., Grotli, M. Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis in Water Using Microwave-Assisted Heating. Organic Letters. 11 (20), 4488-4491 (2009).

- Rizzolo, F., Sabatino, G., Chelli, M., Rovero, P., Papini, A. M. A convenient microwave-enhanced solid-phase synthesis of difficult peptide sequences: Case study of Gramicidin A and CSF114(Glc). Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 13 (1-2), 203-208 (2007).

- Matsushita, T., Hinou, H., Kurogochi, M., Shimizu, H., Nishimura, S. Rapid microwave-assisted solid-phase glycopeptide synthesis. Org Lett. 7 (5), 877-880 (2005).

- Nagaike, F., et al. Efficient microwave-assisted tandem N- to S-acyl transfer and thioester exchange for the preparation of a glycosylated peptide thioester. Org Lett. 8 (20), 4465-4468 (2006).

- Naruchi, K., et al. Construction and structural characterization of versatile lactosaminoglycan-related compound library for the synthesis of complex glycopeptides and glycosphingolipids. J. Org. Chem. 71 (26), 9609-9621 (2006).

- Brandt, M., Gammeltoft, S., Jensen, K. J. Microwave heating for solid-phase peptide synthesis: General evaluation and application to 15-mer phosphopeptides. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 12 (4), 349-357 (2006).

- Harris, P. W. R., Williams, G. M., Shepherd, P., Brimble, M. A. The Synthesis of Phosphopeptides Using Microwave-assisted Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 14 (4), 387-392 (2008).

- Qvit, N. Microwave-assisted Synthesis of Cyclic Phosphopeptide on Solid Support. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 85 (3), 300-305 (2014).

- Kato, D., Verhelst, S. H., Sexton, K. B., Bogyo, M. A general solid phase method for the preparation of diverse azapeptide probes directed against cysteine proteases. Org Lett. 7 (25), 5649-5652 (2005).

- Olivos, H. J., Alluri, P. G., Reddy, M. M., Salony, D., Kodadek, T. Microwave-assisted solid-phase synthesis of peptoids. Org Lett. 4 (23), 4057-4059 (2002).

- Gorske, B. C., Jewell, S. A., Guerard, E. J., Blackwell, H. E. Expedient synthesis and design strategies for new peptoid construction. Org Lett. 7 (8), 1521-1524 (2005).

- Grieco, P., et al. Design and microwave-assisted synthesis of novel macrocyclic peptides active at melanocortin receptors: discovery of potent and selective hMC5R receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 51 (9), 2701-2707 (2008).

- Boutard, N., Jamieson, A. G., Ong, H., Lubell, W. D. Structure-Activity Analysis of the Growth Hormone Secretagogue GHRP-6 by alpha- and beta-Amino gamma-Lactam Positional Scanning. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 75 (1), 40-50 (2010).

- Jamieson, A. G., et al. Positional scanning for peptide secondary structure by systematic solid-phase synthesis of amino lactam peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (22), 7917-7927 (2009).

- Hossain, M. A., Bathgate, R. A. D., Tregear, G., Wade, J. D. De Novo Design and Synthesis of Cyclic and Linear Peptides to Mimic the Binding Cassette of Human Relaxin. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1160, 16-19 (2009).

- Fowler, S. A., Stacy, D. M., Blackwell, H. E. Design and synthesis of macrocyclic peptomers as mimics of a quorum sensing signal from Staphylococcus aureus. Org Lett. 10 (12), 2329-2332 (2008).

- Cemazar, M., Craik, D. J. Microwave-assisted Boc-solid phase peptide synthesis of cyclic cysteine-rich peptides. J Pept Sci. 14 (6), 683-689 (2008).

- Miles, S. M., Leatherbarrow, R. J., Marsden, S. P., Coates, W. J. Synthesis and bio-assay of RCM-derived Bowman-Birk inhibitor analogues. Org Biomol Chem. 2 (3), 281-283 (2004).

- Murray, J. K., et al. Efficient synthesis of a beta-peptide combinatorial library with microwave irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (38), 13271-13280 (2005).

- Churchill, E. N., Qvit, N., Mochly-Rosen, D. Rationally designed peptide regulators of protein kinase. C. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20 (1), 25-33 (2009).

- Mochly-Rosen, D., Qvit, N. Peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. chimica Oggi / CHEMISTRY today. 28 (1), 14-16 (2010).

- Qvit, N., Mochly-Rosen, D. Highly specific modulators of protein kinase C localization: applications to heart failure. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Mech. 7 (2), e87-e93 (2010).

- Mougneau, E., et al. Expression cloning of a protective Leishmania antigen. Science. 268 (5210), 563-566 (1995).

- Kelly, B. L., Stetson, D. B., Locksley, R. M. Leishmania major LACK antigen is required for efficient vertebrate parasitization. J. Exp. Med. 198 (11), 1689-1698 (2003).

- Choudhury, K., et al. Trypanosomatid RACK1 orthologs show functional differences associated with translation despite similar roles in Leishmania pathogenesis. PLoS One. 6 (6), e20710 (2011).

- Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza, G., Taladriz, S., Marquet, A., Larraga, V. Molecular cloning, cell localization and binding affinity to DNA replication proteins of the p36/LACK protective antigen from Leishmania infantum. Eur. J. Biochem. 259 (3), 909-916 (1999).

- Gump, J. M., Dowdy, S. F. TAT transduction: the molecular mechanism and therapeutic prospects. Trends Mol. Med. 13 (10), 443-448 (2007).

- Aletras, A., Barlos, K., Gatos, D., Koutsogianni, S., Mamos, P. Preparation of the very acid-sensitive Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-OH. Application in the synthesis of side-chain to side-chain cyclic peptides and oligolysine cores suitable for the solid-phase assembly of MAPs and TASPs. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 45 (5), 488-496 (1995).

- Li, D., Elbert, D. L. The kinetics of the removal of the N-methyltrityl (Mtt) group during the synthesis of branched peptides. J. Pept. Res. 60 (5), 300-303 (2002).

- Bourel, L., Carion, O., Gras-Masse, H., Melnyk, O. The deprotection of Lys(Mtt) revisited. J Pept Sci. 6 (6), 264-270 (2000).

- Tran, H., Gael, S. L., Connolly, M. D., Zuckermann, R. N. Solid-phase submonomer synthesis of peptoid polymers and their self-assembly into highly-ordered nanosheets. J Vis Exp. (57), e3373 (2011).

- Kaiser, E., Colescot, R. L., Bossinge, C. D., Cook, P. I. Color Test for Detection of Free Terminal Amino Groups in Solid-Phase Synthesis of Peptides. Anal. Biochem. 34 (2), 595-598 (1970).

- Christensen, T. Qualitative Test for Monitoring Coupling Completeness in Solid-Phase Peptide-Synthesis Using Chloranil. Acta Chem. Scand. Ser.B-Org. Chem. Biochem. 33 (10), 763-766 (1979).

- Qvit, N., Crapster, J. A. Peptides that Target Protein-Protein Interactions as an Anti-Parasite Strategy. chimica Oggi / CHEMISTRY today. 32 (6), 62-66 (2014).

- Byk, G., et al. Synthesis and biological activity of NK-1 selective, N-backbone cyclic analogs of the C-terminal hexapeptide of substance P. J. Med. Chem. 39 (16), 3174-3178 (1996).

- King, D. S., Fields, C. G., Fields, G. B. A cleavage method which minimizes side reactions following Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 36 (3), 255-266 (1990).

- Pedersen, S. L., Tofteng, A. P., Malik, L., Jensen, K. J. Microwave heating in solid-phase peptide synthesis. Chemical Society Reviews. 41 (5), 1826-1844 (2012).

- Colangelo, A. M., et al. A new nerve growth factor-mimetic peptide active on neuropathic pain in rats. J. Neurosci. 28 (11), 2698-2709 (2008).

- Mesfin, F. B., Andersen, T. T., Jacobson, H. I., Zhu, S., Bennett, J. A. Development of a synthetic cyclized peptide derived from alpha-fetoprotein that prevents the growth of human breast cancer. J. Pept. Res. 58 (3), 246-256 (2001).

- Mizejewski, G. J., Muehlemann, M., Dauphinee, M. Update of alpha fetoprotein growth-inhibitory peptides as biotherapeutic agents for tumor growth and metastasis. Chemotherapy. 52 (2), 83-90 (2006).