الكشف عن وظيفية غير الترميز المتغيرات الوراثية عن طريق الكهربي التنقل التحول الفحص (EMSA) والحمض النووي تقارب الهطول الفحص (ضبا)

Summary

We present a strategic plan and protocol for identifying non-coding genetic variants affecting transcription factor (TF) DNA binding. A detailed experimental protocol is provided for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genotype-dependent TF DNA binding.

Abstract

Population and family-based genetic studies typically result in the identification of genetic variants that are statistically associated with a clinical disease or phenotype. For many diseases and traits, most variants are non-coding, and are thus likely to act by impacting subtle, comparatively hard to predict mechanisms controlling gene expression. Here, we describe a general strategic approach to prioritize non-coding variants, and screen them for their function. This approach involves computational prioritization using functional genomic databases followed by experimental analysis of differential binding of transcription factors (TFs) to risk and non-risk alleles. For both electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genetic variants, a synthetic DNA oligonucleotide (oligo) is used to identify factors in the nuclear lysate of disease or phenotype-relevant cells. For EMSA, the oligonucleotides with or without bound nuclear factors (often TFs) are analyzed by non-denaturing electrophoresis on a tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gel. For DAPA, the oligonucleotides are bound to a magnetic column and the nuclear factors that specifically bind the DNA sequence are eluted and analyzed through mass spectrometry or with a reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Western blot analysis. This general approach can be widely used to study the function of non-coding genetic variants associated with any disease, trait, or phenotype.

Introduction

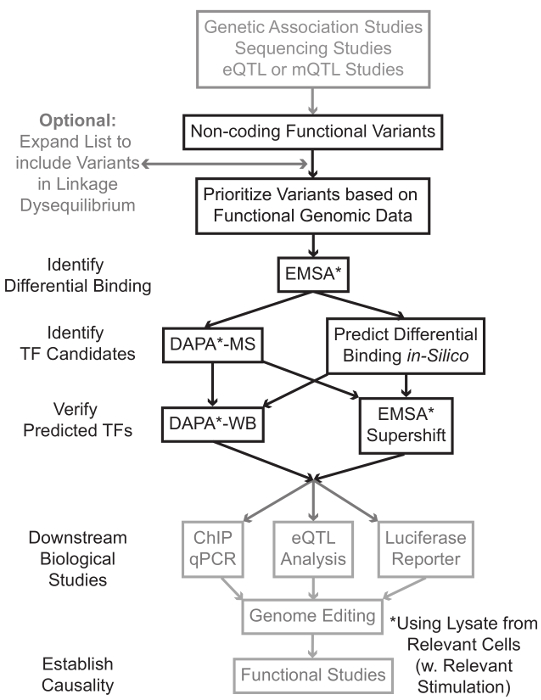

التسلسل والدراسات التنميط الجيني أساس، بما في ذلك دراسات الجينوم على نطاق الرابطة (GWAS)، دراسات المرشح مكان، وأعماق التسلسل الدراسات، وقد حددت العديد من المتغيرات الجينية التي ترتبط إحصائيا مع المرض، وسمة، أو النمط الظاهري. وخلافا للتوقعات في وقت مبكر، وتقع معظم هذه المتغيرات (85-93٪) في مناطق غير الترميز ولا تغيير تسلسل الأحماض الأمينية للبروتينات 1،2. تفسير وظيفة من هذه المتغيرات غير الترميز وتحديد الآليات البيولوجية وربطها لمرض المرتبطة بها، وقد ثبت سمة، أو النمط الظاهري تحديا 3-6. لقد قمنا بتطوير استراتيجية عامة لتحديد الآليات الجزيئية التي تصل المتغيرات إلى النمط الظاهري وسيط مهم – التعبير الجيني. تم تصميم هذا الخط على وجه التحديد لتحديد التشكيل من فريق العمل ملزم المتغيرات الجينية. هذه الاستراتيجية يجمع بين النهج الحسابية وتقنيات البيولوجيا الجزيئية التي تهدف إلى التنبؤالآثار البيولوجية من المتغيرات مرشح في سيليكون، وتحقق هذه التنبؤات تجريبيا (الشكل 1).

الشكل 1: النهج الاستراتيجي لتحليل خطوات غير ترميز المتغيرات الجينية التي لم يتم تضمينها في بروتوكول مفصلة المرتبطة مظللة باللون الرمادي هذا المخطوط الرجاء انقر هنا لعرض نسخة أكبر من هذا الرقم.

في كثير من الحالات، من المهم أن تبدأ من خلال توسيع قائمة المتغيرات بحيث يشمل جميع من في ارتفاع الربط-اختلال التوازن (LD) مع كل متغير يرتبط إحصائيا. LD هو مقياس لجمعية غير عشوائية من أليل على موقعين الكروموسومات المختلفة، والتي يمكن أن تقاس ص 2 الإحصائية 7. ص 2 هو مقياس للينكاجي اختلال التوازن بين الخيارين، مع ص 2 = 1 تدل على الربط المثالي بين الخيارين. تم العثور على الأليلات في LD عالية للمشاركة في فصل على كروموسوم عبر السكان الأسلاف. لا تشمل صفائف التنميط الجيني الحالية كافة المتغيرات المعروفة في الجينوم البشري. بدلا من ذلك، فإنها تستغل LD داخل الجينوم البشري وتشمل مجموعة فرعية من المتغيرات المعروفة التي تعمل كوكلاء للالمتغيرات الأخرى داخل منطقة معينة من LD 8. وهكذا، وهو البديل من دون أي نتيجة البيولوجية قد تترافق مع مرض معين لأنه في LD مع السببية البديل، البديل مع التأثير البيولوجي ذات مغزى. من الناحية الإجرائية، فمن المستحسن لتحويل الإصدار الأخير من 1000 الجينوم المشروع 9 ملفات دعوة البديل (VCF) في الملفات الثنائية متوافقة مع طقطقة 10،11، أداة مفتوحة المصدر للتحليل جمعية الجينوم بأكمله. وفي وقت لاحق، كل المتغيرات الجينية الأخرى مع LD ص 2> 0.8 مع كل فا الجيني المدخلاتويمكن تحديد RIANT كمرشحين. ومن المهم استخدام السكان إشارة المناسب لهذا خطوة- على سبيل المثال، إذا تم تحديد البديل في المواد من أصول أوروبية، وينبغي استخدام البيانات من موضوعات من أصل مماثل للتوسع دينار.

التوسع LD غالبا ما يؤدي إلى العشرات من المتغيرات مرشح، وأنه من المرجح أن جزءا صغيرا فقط من هذه تسهم في آلية المرض. في كثير من الأحيان، أصبح في حكم المستحيل لدراسة التجربة كل من هذه المتغيرات بشكل فردي. ولذا فمن المفيد الاستفادة من آلاف من مجموعات البيانات الجينومية الوظيفية المتاحة علنا كمرشح لتحديد أولويات المتغيرات. على سبيل المثال، اتحاد ترميز 12 قد أنجز الآلاف من تجارب رقاقة وما يليها واصفا ربط TFS والعوامل المشتركة، وعلامات هيستون في مجموعة واسعة من السياقات، جنبا إلى جنب مع البيانات لونين الوصول من التقنيات مثل الدناز تسلسل 13، أي تي أي سي -seq 14، وFAIRE وما يليها 15. DatabASES وخوادم الويب مثل متصفح UCSC الجينوم 16، خارطة الطريق Epigenomics 17، مخطط Epigenome 18، Cistrome 19، وإعادة رسم خريطة 20 توفر حرية الوصول إلى البيانات التي تنتجها هذه وتقنيات تجريبية أخرى عبر مجموعة واسعة من أنواع الخلايا والشروط. عندما يكون هناك الكثير من المتغيرات لدراسة التجربة، وهذه البيانات يمكن استخدامها لتحديد أولويات تلك التي تقع داخل المناطق التنظيمية المحتملة في أنواع الخلايا والأنسجة ذات الصلة. وعلاوة على ذلك، في الحالات التي يكون فيها البديل هو في ذروته في الشذرة وما يليها لبروتين معين، ويمكن لهذه البيانات توفير يؤدي المحتملة فيما يتعلق TF معين (ق) أو العوامل المشتركة التي الملزم قد تؤثر.

بعد ذلك، يتم فحص المتغيرات الناتجة الأولوية تجريبيا للتحقق من صحة توقع البروتين تعتمد على التركيب الوراثي ملزمة باستخدام EMSA 21،22. EMSA يقيس التغير في هجرة بنسبة ضئيلة على غير الحد هلام TBE. وحضنت بنسبة ضئيلة fluorescently المسمى معالمحللة النووي، وربط العوامل النووية في اعاقة حركة جزئية على هلام. في هذه الطريقة، بنسبة ضئيلة أن تربط بين العوامل النووية المزيد من سيقدم على أنه إشارة الفلورسنت أقوى على المسح الضوئي. والجدير بالذكر، EMSA لا تتطلب التنبؤات حول بروتينات معينة التي ستتأثر ملزم.

وبمجرد تحديد المتغيرات التي تقع داخل المناطق التنظيمية توقع وتكون قادرة على العوامل النووية ملزمة بشكل مختلف، واستخدام طرق الحسابية للتنبؤ TF معين (ق) الذي ملزمة لأنها قد تؤثر. ونحن نفضل استخدام CIS-BP 23،24، RegulomeDB 25، UniProbe 26، وJASPAR 27. وبمجرد تحديد مرشح TFS، هذه التنبؤات يمكن اختبار على وجه التحديد باستخدام أجسام مضادة ضد هذه TFS (EMSA-supershifts وضبا-الغرب). ينطوي على EMSA-supershift إضافة الضد-TF محددة لالمحللة النووي وبنسبة ضئيلة. ونتيجة إيجابية في EMSA-supershift هي represented تحولا آخر في الفرقة EMSA، أو خسارة من الفرقة (إعادة النظر في المرجع 28). في ضبا التكميلي، يتم تحضين على الوجهين بنسبة ضئيلة من 5'المعقدة البيروكسيديز تحتوي على البديل و 20 قاعدة الزوج المرافقة النيوكليوتيدات مع المحللة النووي من نوع من الخلايا ذات الصلة (ق) لالتقاط أي عوامل النووية ملزمة على وجه التحديد oligos. ويجمد بنسبة ضئيلة على الوجهين النووي مجمع عامل من قبل streptavidin ميكروبيدات في عمود المغناطيسي. يتم جمع العوامل النووية ملزمة مباشرة من خلال شطف 29،48. ويمكن بعد ذلك التنبؤات ملزم يتم تقييمها بواسطة لطخة غربية باستخدام الأجسام المضادة المحددة للبروتين. في الحالات التي لا توجد توقعات واضحة، أو الكثير من التوقعات، وelutions من البديل سحب هبوطا من التجارب ضبا يمكن إرسالها إلى نواة البروتينات لتحديد TFS مرشح باستخدام مطياف الكتلة، والتي يمكن بعد ذلك يمكن التحقق من صحة استخدام هذه الموصوفة سابقا أساليب.

في ما تبقى من الاعتده، يتم توفير بروتوكول مفصلة عن EMSA وضبا تحليل المتغيرات الجينية.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

وعلى الرغم من التقدم في مجال تكنولوجيا التسلسل والتنميط الجيني قد تتعزز بشكل كبير قدرتنا على تحديد المتغيرات الجينية المرتبطة بالمرض، لدينا القدرة على فهم الآليات الوظيفية تتأثر هذه المتغيرات متخلفة. مصدر رئيسي من المشكلة هو أن العديد من المتغيرات المرتبطة الم?…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank Erin Zoller, Jessica Bene, and Lindsey Hays for input and direction in protocol development. MTW was supported in part by NIH R21 HG008186 and a Trustee Award grant from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. ZHP was supported in part by T32 GM063483-13.

Materials

| Custom DNA Oligonucleotides | Integrated DNA Technologies | http://www.idtdna.com/site/order/oligoentry | |

| Potassium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP366-500 | KCl, for CE buffer |

| HEPES (1M) | Fisher Scientific | 15630-080 | For CE and NE buffer |

| EDTA (0.5M), pH 8.0 | Life Technologies | R1021 | For CE, NE, and annealing buffer |

| Sodium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP358-1 | NaCl, for NE buffer |

| Tris-HCl (1M), pH 8.0 | Invitrogen | BP1756-100 | For annealing buffer |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (1X) | Fisher Scientific | MT21040CM | PBS, for cell wash |

| DL-Dithiothreitol solution (1M) | Sigma | 646563 | Reducing agent |

| PMSF | Thermo Scientific | 36978 | Protease Inhibitor |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Thermo Scientific | 78420 | Prevents dephosphorylation of TFs |

| Nonidet P-40 Substitute | IBI Scientific | IB01140 | NP-40, for nuclear extraction |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | For measuring protein concentration |

| Odyssey EMSA Buffer Kit | Licor | 829-07910 | Contains all necessary EMSA buffers |

| TBE Gels, 6%, 12 Wells | Invitrogen | EC6265BOX | For EMSA |

| TBE Buffer (10X) | Thermo Scientific | B52 | For EMSA |

| FactorFinder Starting Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-092-318 | Contains all necessary DAPA buffers |

| Licor Odyssey CLx | Licor | Recommended scanner for DAPA/EMSA | |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic | Gibco | 15240-062 | Contains 10,000 units/mL of penicillin, 10,000 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 25 µg/mL of Fungizone® Antimycotic |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Gibco | 26140-079 | FBS, for culture media |

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Gibco | 22400-071 | Contains L-glutamine and 25mM HEPES |

Referências

- Hindorff, L. A., et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (23), 9362-9367 (2009).

- Maurano, M. T., et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 337 (6099), 1190-1195 (2012).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 30 (11), 1095-1106 (2012).

- Paul, D. S., Soranzo, N., Beck, S. Functional interpretation of non-coding sequence variation: concepts and challenges. Bioessays. 36 (2), 191-199 (2014).

- Zhang, F., Lupski, J. R. Non-coding genetic variants in human disease. Hum Mol Genet. , (2015).

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 152 (6), 1237-1251 (2013).

- Slatkin, M. Linkage disequilibrium–understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat Rev Genet. 9 (6), 477-485 (2008).

- Bush, W. S., Moore, J. H. Chapter 11: Genome-wide association studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 8 (12), e1002822 (2012).

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 491 (7422), 56-65 (2012).

- Chang, C. C., et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 4, 7 (2015).

- Purcell, S., et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 81 (3), 559-575 (2007).

- ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 489 (7414), 57-74 (2012).

- Crawford, G. E., et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS). Genome Res. 16 (1), 123-131 (2006).

- Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y., Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 10 (12), 1213-1218 (2013).

- Giresi, P. G., Kim, J., McDaniell, R. M., Iyer, V. R., Lieb, J. D. FAIRE Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 17 (6), 877-885 (2007).

- Kent, W. J., et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12 (6), 996-1006 (2002).

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 518 (7539), 317-330 (2015).

- Martens, J. H., Stunnenberg, H. G. BLUEPRINT: mapping human blood cell epigenomes. Haematologica. 98 (10), 1487-1489 (2013).

- Liu, T., et al. Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biol. 12 (8), R83 (2011).

- Griffon, A., et al. Integrative analysis of public ChIP-seq experiments reveals a complex multi-cell regulatory landscape. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (4), e27 (2015).

- Staudt, L. M., et al. A lymphoid-specific protein binding to the octamer motif of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 323 (6089), 640-643 (1986).

- Singh, H., Sen, R., Baltimore, D., Sharp, P. A. A nuclear factor that binds to a conserved sequence motif in transcriptional control elements of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 319 (6049), 154-158 (1986).

- Weirauch, M. T., et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell. 158 (6), 1431-1443 (2014).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (Database issue), D930-D934 (2012).

- Boyle, A. P., et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1790-1797 (2012).

- Hume, M. A., Barrera, L. A., Gisselbrecht, S. S., Bulyk, M. L. UniPROBE, update 2015: new tools and content for the online database of protein-binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (Database issue), D117-D122 (2015).

- Mathelier, A., et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), 142-147 (2014).

- Smith, M. F., Delbary-Gossart, S. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA). Methods Mol Med. 50, 249-257 (2001).

- Franza, B. R., Josephs, S. F., Gilman, M. Z., Ryan, W., Clarkson, B. Characterization of cellular proteins recognizing the HIV enhancer using a microscale DNA-affinity precipitation assay. Nature. 330 (6146), 391-395 (1987).

- . BCA Protein Assay Kit: User Guide Available from: https://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/MAN0011430_Pierce_BCA_Protein_Asy_UG.pdf (2014)

- Wijeratne, A. B., et al. Phosphopeptide separation using radially aligned titania nanotubes on titanium wire. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 7 (21), 11155-11164 (2015).

- Silva, J. M., McMahon, M. The Fastest Western in Town: A Contemporary Twist on the Classic Western Blot Analysis. J. Vis. Exp. (84), (2014).

- Lu, X., et al. Lupus Risk Variant Increases pSTAT1 Binding and Decreases ETS1 Expression. Am J Hum Genet. 96 (5), 731-739 (2015).

- Ramana, C. V., Chatterjee-Kishore, M., Nguyen, H., Stark, G. R. Complex roles of Stat1 in regulating gene expression. Oncogene. 19 (21), 2619-2627 (2000).

- Fillebeen, C., Wilkinson, N., Pantopoulos, K. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for the Study of RNA-Protein Interactions: The IRE/IRP Example. J. Vis. Exp. (94), e52230 (2014).

- Heng, T. S., Painter, M. W. Immunological Genome Project, C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 9 (10), 1091-1094 (2008).

- Wu, C., et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 10 (11), R130 (2009).

- Wu, C., Macleod, I., Su, A. I. BioGPS and MyGene.info: organizing online, gene-centric information. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (Database issue), D561-D565 (2013).

- Wang, J., et al. Sequence features and chromatin structure around the genomic regions bound by 119 human transcription factors. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1798-1812 (2012).

- Holden, N. S., Tacon, C. E. Principles and problems of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 63 (1), 7-14 (2011).

- Xu, J., Liu, H., Park, J. S., Lan, Y., Jiang, R. Osr1 acts downstream of and interacts synergistically with Six2 to maintain nephron progenitor cells during kidney organogenesis. Development. 141 (7), 1442-1452 (2014).

- Yang, T. -. P., et al. Genevar: a database and Java application for the analysis and visualization of SNP-gene associations in eQTL studies. Bioinformatics. 26 (19), 2474-2476 (2010).

- Fort, A., et al. A liver enhancer in the fibrinogen gene cluster. Blood. 117 (1), 276-282 (2011).

- Solberg, N., Krauss, S. Luciferase assay to study the activity of a cloned promoter DNA fragment. Methods Mol Biol. 977, 65-78 (2013).

- Rahman, M., et al. A repressor element in the 5′-untranslated region of human Pax5 exon 1A. Gene. 263 (1-2), 59-66 (2001).

- Mali, P., et al. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science. 339 (6121), 823-826 (2013).