전기 영동 이동성 분석 (EMSA) 및 Shift 키를 사용하여 기능 비 코딩 유전자 변형에 대한 심사 DNA 화성 강수 분석 (DAPA)

Summary

We present a strategic plan and protocol for identifying non-coding genetic variants affecting transcription factor (TF) DNA binding. A detailed experimental protocol is provided for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genotype-dependent TF DNA binding.

Abstract

Population and family-based genetic studies typically result in the identification of genetic variants that are statistically associated with a clinical disease or phenotype. For many diseases and traits, most variants are non-coding, and are thus likely to act by impacting subtle, comparatively hard to predict mechanisms controlling gene expression. Here, we describe a general strategic approach to prioritize non-coding variants, and screen them for their function. This approach involves computational prioritization using functional genomic databases followed by experimental analysis of differential binding of transcription factors (TFs) to risk and non-risk alleles. For both electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genetic variants, a synthetic DNA oligonucleotide (oligo) is used to identify factors in the nuclear lysate of disease or phenotype-relevant cells. For EMSA, the oligonucleotides with or without bound nuclear factors (often TFs) are analyzed by non-denaturing electrophoresis on a tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gel. For DAPA, the oligonucleotides are bound to a magnetic column and the nuclear factors that specifically bind the DNA sequence are eluted and analyzed through mass spectrometry or with a reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Western blot analysis. This general approach can be widely used to study the function of non-coding genetic variants associated with any disease, trait, or phenotype.

Introduction

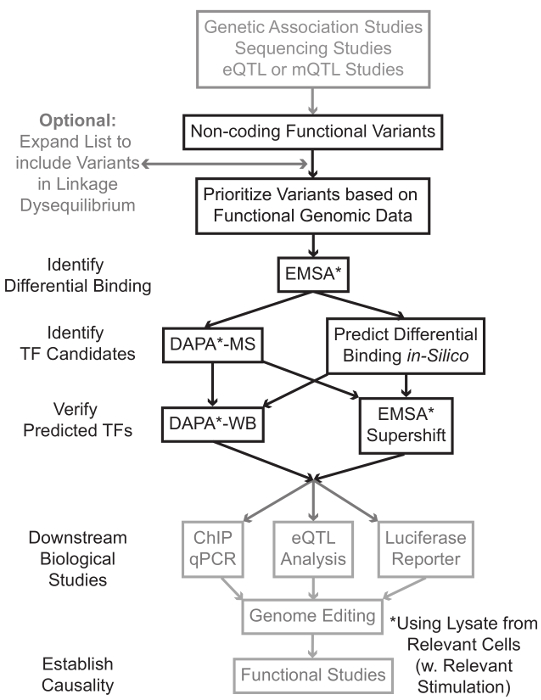

시퀀싱 및 게놈 넓은 협회 연구 (GWAS), 후보의 궤적 연구를 포함하여 유전자형을 기반으로 연구, 그리고 깊은 시퀀싱 연구는 통계적으로 질병, 특성, 또는 표현형과 관련된 많은 유전자 변형을 확인했다. 초기 예측과는 반대로, 이러한 변형 (85-93%)의 대부분은 비 – 코딩 영역에 위치하는 단백질 1,2의 아미노산 서열을 변경하지 않는다. 이들 비 – 코딩 변이체의 기능을 해석하고 관련된 질환에 접속 생물학적 메커니즘을 결정하는 단계, 특성, 또는 표현형 3-6 도전 입증되었다. 유전자 발현 – 우리는 중요한 중간 표현형 변이를 연결하는 분자 메커니즘을 식별하기위한 일반적인 전략을 개발했다. 이 파이프 라인은 특히 유전 적 변이에 의해 결합 TF의 변조를 식별 할 수 있도록 설계되었습니다. 이 전략은 예측하기위한 계산 방법과 분자 생물학 기술을 결합생물학적 인 실리코 후보 변종의 효과 및 확인이 예측 경험적으로 (그림 1).

그림 1 :.. 회색 음영이 원고와 관련된 상세한 프로토콜에 포함되지 않은 비 코딩 유전자 변형 단계의 분석을위한 전략적 접근 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

많은 경우, 각각 통계 학적으로 관련된 변이체 높은 링크 – 불평형 (LD)의 모든 것을 포함하는 변이체의 목록을 확대함으로써 시작하는 것이 중요하다. LD는 R 7이 통계에 의해 측정 될 수있는 두 개의 다른 대립 유전자의 염색체 위치에서의 비 – 무작위 교제의 척도이다. R 2는 린의 측정두 가지 변종 사이의 R 2 = 1 나타내는 완벽한 결합으로 두 가지 변형 사이의 케이지는 불균형. 높은 LD의 대립 유전자는 조상의 인구에서 염색체에 공동으로 분리하는 찾을 수 있습니다. 현재 유전자형 배열은 인간 게놈의 모든 알려진 변종을 포함하지 않는다. 대신, 그들은 인간 게놈 내에서 LD을 악용 LD (8)의 특정 지역 내에서 다른 변형에 대한 프록시 역할 알려진 변종의 서브 세트를 포함한다. 이 의미 생물학적 효과와 인과 변형 – 변형와 LD에 있기 때문에, 생물학적 결과없이 변이체는 특정 질환과 연관 될 수있다. 절차 적, 1000 게놈의 최신 버전은 가용 스루풋 10, 11, 전체 게놈 협회 분석을위한 오픈 소스 도구와 호환 바이너리 파일에 9 변형 호출 파일 (VCF)를 프로젝트로 변환하는 것이 좋습니다. 그 후, 각 입력 유전 버지니아와 LD의 R 2> 0.8 다른 모든 유전자 변형쾌활한 후보로서 식별 될 수있다. 변형이 유럽 가계의 주제, 비슷한 조상의 과목에서 데이터가 LD 확장을 사용해야에서 확인 된 경우는,이 스텝 – 예에 대한 적절한 기준 인구를 사용하는 것이 중요합니다.

LD 확장들은 후보 변형 수십 결과 및 이들의 단지 작은 분획이 질병기구에 기여할 것으로 예상된다. 종종, 실험적 개별적으로 각 변형을 조사하기 불가능하다. 변형의 우선 순위를 필터로 공개적으로 사용 가능한 기능 게놈 데이터 세트의 수천을 활용하는 것이 유용하다. 예를 들어, 인 코드 컨소시엄 (12)는의 DNase-SEQ 13 ATAC 같은 기술에서 염색질 접근성 데이터와 함께 콘텍스트의 넓은 범위에서 칩 배열하여 TFS의 결합을 설명하는 실험 및 공동 인자 및 히스톤 마크 수천을 수행 -seq 14 및 서열 FAIRE-15. Datab같은 UCSC 게놈 브라우저 (16), 로드맵 후성 유전체학 (17), 청사진 후성 유전체 (18), Cistrome (19), 및 매핑 20 ASE에 웹 서버는 세포 유형 및 조건의 넓은 범위에 걸쳐 이들과 다른 실험 기법에 의해 생성 된 데이터에 대한 무료 액세스를 제공합니다. 실험적 검토하기에 너무 많은 변형이있을 때, 이러한 데이터는 관련 세포 및 조직 유형의 것으로 조절 영역 내에 위치하는 우선 순위를 사용할 수있다. 또한, 변형 특정 단백질 칩 서열 피크 내에있는 경우,이 데이터는 특정 TF (들) 또는 그의 영향을 줄 수 있습니다 결합 공동 요인으로 잠재적 인 단서를 제공 할 수 있습니다.

다음으로, 우선 순위 결과 변종은 EMSA (21, 22)를 사용하여 결합 예측 유전자형에 의존하는 단백질을 확인하는 실험적으로 상영된다. EMSA은 비 환원성 TBE 겔상에서 올리고의 이동 변화를 측정한다. 형광 표지 올리고는 함께 배양핵 해물, 핵 인자의 결합은 올리고 겔상에서의 이동을 지연시킬 것이다. 이러한 방식으로, 스캔시 강한 형광 신호로 발표 할 예정보다 핵 요소를 결합했다 올리고있다. 특히, EMSA 바인딩 영향을받는 특정 단백질에 대한 예측을 필요로하지 않습니다.

변형이 예측 규제 지역 내에 위치하며, 차동 결합 핵 인자 할 수있는있다가 발견되면, 계산 방법은 누구가에 영향을 줄 수있는 바인딩 특정 TF (들)을 예측하기 위해 사용된다. 우리는 CIS-BP 23, 24, RegulomeDB 25 UniProbe (26), 및이 JasPAR (27)를 사용하는 것을 선호합니다. 후보 TF가 식별되면,이 예측은 구체적으로 다음과 TF (EMSA-supershifts 및 DAPA-서부)에 대한 항체를 사용하여 시험 할 수있다. EMSA-supershift 핵 분해물 및 올리고 TF에 특이 항체의 첨가를 포함한다. EMSA-supershift에서 긍정적 인 결과를 repr입니다EMSA 대역에서 추가의 이동 또는 대역의 손실로 esented (레퍼런스 28에서 검토). 상보 DAPA에서, 변형 및 뉴클레오티드의 측면에 20 염기쌍을 함유하는 5'- 비오틴 올리고 양면은 특히 올리고 결합 핵 인자 캡처 관련된 세포 유형 (들)로부터 핵 파쇄 액과 함께 배양된다. 올리고 이중 핵 인자 복합체는 자기 칼럼에서 마이크로 비드를 스트렙 타비 딘에 의해 고정된다. 결합 된 핵 인자 용출 29,48 통해 직접 수집됩니다. 바인딩 예측이어서 단백질에 특이적인 항체를 사용하여 웨스턴 블롯에 의해 평가 될 수있다. 후속하여 검증 할 수있는 명백한 예측 또는 너무 많은 예측, 질량 분석법을 이용하여 후보의 TF를 식별하기 위해 프로테오믹스 코어로 전송 될 수 DAPA 실험 변이체 풀 – 다운에서 용리가없는 경우에서, 이들은 전술 행동 양식.

articl의 나머지 부분에서즉, 유전자 변형 및 DAPA EMSA 분석 상세한 프로토콜이 제공된다.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

시퀀싱 및 유전형 기술의 발전이 크게 질병과 관련된 유전자 변형을 식별하는 우리의 능력을 강화하고 있지만, 이러한 변형의 영향을 기능적 메커니즘을 이해하는 능력이 떨어지고있다. 문제의 주된 원인 가능성 유전자 발현을 제어하기 어려워-간 예측 메커니즘에 영향을하는 부호화 게놈 영역 많은 질병 관련 변종 N에 위치된다는 것이다. 여기서는 가능성이 많은 비 – 코딩 변이체의 기능에…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank Erin Zoller, Jessica Bene, and Lindsey Hays for input and direction in protocol development. MTW was supported in part by NIH R21 HG008186 and a Trustee Award grant from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. ZHP was supported in part by T32 GM063483-13.

Materials

| Custom DNA Oligonucleotides | Integrated DNA Technologies | http://www.idtdna.com/site/order/oligoentry | |

| Potassium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP366-500 | KCl, for CE buffer |

| HEPES (1M) | Fisher Scientific | 15630-080 | For CE and NE buffer |

| EDTA (0.5M), pH 8.0 | Life Technologies | R1021 | For CE, NE, and annealing buffer |

| Sodium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP358-1 | NaCl, for NE buffer |

| Tris-HCl (1M), pH 8.0 | Invitrogen | BP1756-100 | For annealing buffer |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (1X) | Fisher Scientific | MT21040CM | PBS, for cell wash |

| DL-Dithiothreitol solution (1M) | Sigma | 646563 | Reducing agent |

| PMSF | Thermo Scientific | 36978 | Protease Inhibitor |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Thermo Scientific | 78420 | Prevents dephosphorylation of TFs |

| Nonidet P-40 Substitute | IBI Scientific | IB01140 | NP-40, for nuclear extraction |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | For measuring protein concentration |

| Odyssey EMSA Buffer Kit | Licor | 829-07910 | Contains all necessary EMSA buffers |

| TBE Gels, 6%, 12 Wells | Invitrogen | EC6265BOX | For EMSA |

| TBE Buffer (10X) | Thermo Scientific | B52 | For EMSA |

| FactorFinder Starting Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-092-318 | Contains all necessary DAPA buffers |

| Licor Odyssey CLx | Licor | Recommended scanner for DAPA/EMSA | |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic | Gibco | 15240-062 | Contains 10,000 units/mL of penicillin, 10,000 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 25 µg/mL of Fungizone® Antimycotic |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Gibco | 26140-079 | FBS, for culture media |

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Gibco | 22400-071 | Contains L-glutamine and 25mM HEPES |

Referências

- Hindorff, L. A., et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (23), 9362-9367 (2009).

- Maurano, M. T., et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 337 (6099), 1190-1195 (2012).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 30 (11), 1095-1106 (2012).

- Paul, D. S., Soranzo, N., Beck, S. Functional interpretation of non-coding sequence variation: concepts and challenges. Bioessays. 36 (2), 191-199 (2014).

- Zhang, F., Lupski, J. R. Non-coding genetic variants in human disease. Hum Mol Genet. , (2015).

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 152 (6), 1237-1251 (2013).

- Slatkin, M. Linkage disequilibrium–understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat Rev Genet. 9 (6), 477-485 (2008).

- Bush, W. S., Moore, J. H. Chapter 11: Genome-wide association studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 8 (12), e1002822 (2012).

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 491 (7422), 56-65 (2012).

- Chang, C. C., et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 4, 7 (2015).

- Purcell, S., et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 81 (3), 559-575 (2007).

- ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 489 (7414), 57-74 (2012).

- Crawford, G. E., et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS). Genome Res. 16 (1), 123-131 (2006).

- Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y., Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 10 (12), 1213-1218 (2013).

- Giresi, P. G., Kim, J., McDaniell, R. M., Iyer, V. R., Lieb, J. D. FAIRE Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 17 (6), 877-885 (2007).

- Kent, W. J., et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12 (6), 996-1006 (2002).

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 518 (7539), 317-330 (2015).

- Martens, J. H., Stunnenberg, H. G. BLUEPRINT: mapping human blood cell epigenomes. Haematologica. 98 (10), 1487-1489 (2013).

- Liu, T., et al. Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biol. 12 (8), R83 (2011).

- Griffon, A., et al. Integrative analysis of public ChIP-seq experiments reveals a complex multi-cell regulatory landscape. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (4), e27 (2015).

- Staudt, L. M., et al. A lymphoid-specific protein binding to the octamer motif of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 323 (6089), 640-643 (1986).

- Singh, H., Sen, R., Baltimore, D., Sharp, P. A. A nuclear factor that binds to a conserved sequence motif in transcriptional control elements of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 319 (6049), 154-158 (1986).

- Weirauch, M. T., et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell. 158 (6), 1431-1443 (2014).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (Database issue), D930-D934 (2012).

- Boyle, A. P., et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1790-1797 (2012).

- Hume, M. A., Barrera, L. A., Gisselbrecht, S. S., Bulyk, M. L. UniPROBE, update 2015: new tools and content for the online database of protein-binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (Database issue), D117-D122 (2015).

- Mathelier, A., et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), 142-147 (2014).

- Smith, M. F., Delbary-Gossart, S. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA). Methods Mol Med. 50, 249-257 (2001).

- Franza, B. R., Josephs, S. F., Gilman, M. Z., Ryan, W., Clarkson, B. Characterization of cellular proteins recognizing the HIV enhancer using a microscale DNA-affinity precipitation assay. Nature. 330 (6146), 391-395 (1987).

- . BCA Protein Assay Kit: User Guide Available from: https://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/MAN0011430_Pierce_BCA_Protein_Asy_UG.pdf (2014)

- Wijeratne, A. B., et al. Phosphopeptide separation using radially aligned titania nanotubes on titanium wire. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 7 (21), 11155-11164 (2015).

- Silva, J. M., McMahon, M. The Fastest Western in Town: A Contemporary Twist on the Classic Western Blot Analysis. J. Vis. Exp. (84), (2014).

- Lu, X., et al. Lupus Risk Variant Increases pSTAT1 Binding and Decreases ETS1 Expression. Am J Hum Genet. 96 (5), 731-739 (2015).

- Ramana, C. V., Chatterjee-Kishore, M., Nguyen, H., Stark, G. R. Complex roles of Stat1 in regulating gene expression. Oncogene. 19 (21), 2619-2627 (2000).

- Fillebeen, C., Wilkinson, N., Pantopoulos, K. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for the Study of RNA-Protein Interactions: The IRE/IRP Example. J. Vis. Exp. (94), e52230 (2014).

- Heng, T. S., Painter, M. W. Immunological Genome Project, C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 9 (10), 1091-1094 (2008).

- Wu, C., et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 10 (11), R130 (2009).

- Wu, C., Macleod, I., Su, A. I. BioGPS and MyGene.info: organizing online, gene-centric information. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (Database issue), D561-D565 (2013).

- Wang, J., et al. Sequence features and chromatin structure around the genomic regions bound by 119 human transcription factors. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1798-1812 (2012).

- Holden, N. S., Tacon, C. E. Principles and problems of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 63 (1), 7-14 (2011).

- Xu, J., Liu, H., Park, J. S., Lan, Y., Jiang, R. Osr1 acts downstream of and interacts synergistically with Six2 to maintain nephron progenitor cells during kidney organogenesis. Development. 141 (7), 1442-1452 (2014).

- Yang, T. -. P., et al. Genevar: a database and Java application for the analysis and visualization of SNP-gene associations in eQTL studies. Bioinformatics. 26 (19), 2474-2476 (2010).

- Fort, A., et al. A liver enhancer in the fibrinogen gene cluster. Blood. 117 (1), 276-282 (2011).

- Solberg, N., Krauss, S. Luciferase assay to study the activity of a cloned promoter DNA fragment. Methods Mol Biol. 977, 65-78 (2013).

- Rahman, M., et al. A repressor element in the 5′-untranslated region of human Pax5 exon 1A. Gene. 263 (1-2), 59-66 (2001).

- Mali, P., et al. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science. 339 (6121), 823-826 (2013).