Скрининг для функционального Некодирующих генетических вариантов Использование электрофоретической подвижности Сдвиг анализа (EMSA) и ДНК-сродства осадков Анализ (DAPA)

Summary

We present a strategic plan and protocol for identifying non-coding genetic variants affecting transcription factor (TF) DNA binding. A detailed experimental protocol is provided for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genotype-dependent TF DNA binding.

Abstract

Population and family-based genetic studies typically result in the identification of genetic variants that are statistically associated with a clinical disease or phenotype. For many diseases and traits, most variants are non-coding, and are thus likely to act by impacting subtle, comparatively hard to predict mechanisms controlling gene expression. Here, we describe a general strategic approach to prioritize non-coding variants, and screen them for their function. This approach involves computational prioritization using functional genomic databases followed by experimental analysis of differential binding of transcription factors (TFs) to risk and non-risk alleles. For both electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genetic variants, a synthetic DNA oligonucleotide (oligo) is used to identify factors in the nuclear lysate of disease or phenotype-relevant cells. For EMSA, the oligonucleotides with or without bound nuclear factors (often TFs) are analyzed by non-denaturing electrophoresis on a tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gel. For DAPA, the oligonucleotides are bound to a magnetic column and the nuclear factors that specifically bind the DNA sequence are eluted and analyzed through mass spectrometry or with a reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Western blot analysis. This general approach can be widely used to study the function of non-coding genetic variants associated with any disease, trait, or phenotype.

Introduction

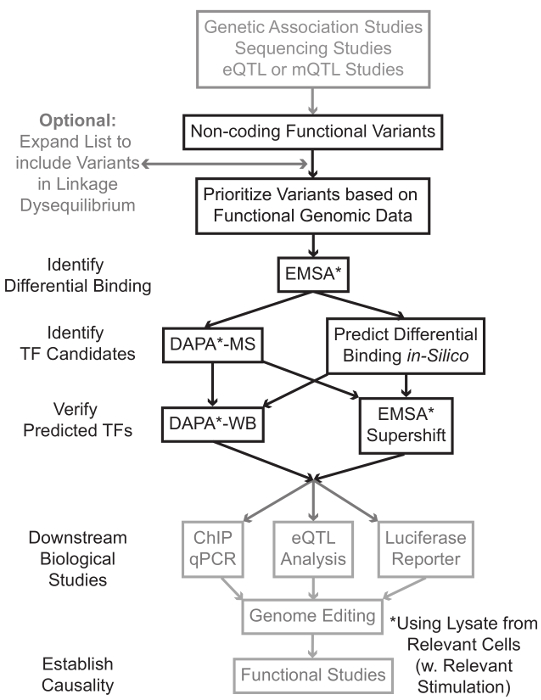

Секвенирования и генотипирования на основе исследований, включая геномные исследования ассоциации (GWAS), кандидат исследований локуса, и глубокие секвенирования исследования, выявили множество генетических вариантов, которые статистически связаны с заболеванием, признаком, или фенотипа. Вопреки ранних предсказаний, большинство из этих вариантов (85-93%) расположены в некодирующих областей и не изменяют аминокислотную последовательность белков 1,2. Интерпретируя функции этих некодирующих вариантов и определения биологических механизмов , связывающих их с сопутствующей болезни, признак или фенотип оказался непростым 3-6. Мы разработали общую стратегию для выявления молекулярных механизмов, связывающих варианты к важному промежуточного фенотипа – экспрессии генов. Этот трубопровод разработан специально для идентификации модуляции TF связывания генетических вариантов. Эта стратегия сочетает в себе вычислительные подходы и методы молекулярной биологии, направленных предсказатьбиологические эффекты вариантов кандидатов в силикомарганца, и проверить эти предсказания эмпирически (рисунок 1).

Рисунок 1:.. Стратегический подход для анализа некодирующих генетические варианты шагов, которые не включены в подробный протокол , связанный с этой рукописи заштрихованы серым цветом Пожалуйста , нажмите здесь , чтобы посмотреть увеличенную версию этой фигуры.

Во многих случаях, важно, чтобы начать путем расширения списка вариантов, чтобы включить все те, в высокой рычажной-неравновесия (LD) с каждым статистически связанным вариантом. ЛД является мерой неслучайной ассоциации аллелей двух различных хромосомных положениях, которые могут быть измерены с помощью R 2 статистики 7. R 2 представляет собой меру линКейдж неравновесие между двумя вариантами, с R 2 = 1 , обозначающее совершенной связи между двумя вариантами. Аллели в высокой LD оказываются совместно разделять на хромосоме через родовые популяции. Современные генотипирования массивы не включают в себя все известные варианты в геноме человека. Вместо этого они используют ЛД внутри генома человека и включают в себя подмножество известных вариантов , которые действуют в качестве прокси для других вариантов в пределах определенной области LD 8. Таким образом, вариант без какого-либо биологического последствие может быть связан с конкретным заболеванием, потому что это в LD с причинным вариантом: вариант с значимого биологического эффекта. С процедурной точки зрения рекомендуется преобразовать последний выпуск 1000 геномов проекта 9 файлов вариант вызова (VCF) в двоичные файлы , совместимые с Plink 10,11, инструмент с открытым исходным кодом для анализа всего генома ассоциации. Впоследствии все другие генетические варианты с LD г 2> 0,8 с каждым входом генетической ваRiant могут быть идентифицированы в качестве кандидатов. Важно использовать соответствующий ссылочный населения для этого , например , Step – , если вариант был выявлен у пациентов европейского происхождения, данные от субъектов аналогичного происхождения должны быть использованы для расширения LD.

Расширение LD часто приводит десятки вариантов кандидатов, и вполне вероятно, что лишь небольшая часть из них внести свой вклад в механизм заболевания. Часто, это неосуществимо экспериментально исследовать каждый из этих вариантов по отдельности. Поэтому полезно использовать тысячи доступных функциональных публично геномных наборов данных в качестве фильтра для определения приоритетности вариантов. Например, КОДИРОВАНИЯ консорциум 12 выполнил тысячи чиповых-сл экспериментов , описывающих связывание ТФ и сопутствующих факторов и гистонов марок в широком диапазоне контекстов, наряду с данными хроматина доступности от технологий , таких как ДНКазы сл 13, ATAC -seq 14 и FAIRE-15 сл. Databтузы и веб – серверы , такие как браузера УСК генома 16, Дорожная карта Epigenomics 17 Blueprint эпигеном 18, Cistrome 19 и ReMap 20 обеспечивают свободный доступ к данным , полученных с помощью этих и других экспериментальных методов в широком диапазоне типов и условий клеток. Когда есть слишком много вариантов, чтобы проверить экспериментально, эти данные могут быть использованы для приоритеты тех, которые находятся в пределах возможных регуляторных областей в соответствующих тканей и клеток типов. Кроме того, в тех случаях, когда вариант в микросхеме-сл пика для специфического белка, эти данные могут обеспечить потенциальных клиентов, как к специфическому TF (ами) или кофакторов, связывание может затрагивающий.

Далее, полученные по приоритетам варианты экспериментально скринингу для проверки связывания с использованием EMSA 21,22 предсказанную генотип-зависимого белка. EMSA измеряет изменение миграции олиго на невосстановительной геле КЭ. Флуоресцентно меченных олиго инкубируют сядерный лизат, и связывание ядерных факторов замедлит движение олиго на геле. Таким образом, олиго-, который связан больше ядерных факторов представит в качестве более сильного флуоресцентного сигнала при сканировании. Следует отметить, что EMSA не требует предсказания о специфических белков, связывание будут затронуты.

После того, как варианты идентифицируются, которые расположены в пределах прогнозируемых регуляторных областей и способны дифференцированно связывания ядерных факторов, вычислительные методы используются для прогнозирования конкретный TF (ы), связывание которого они могут повлиять. Мы предпочитаем использовать CIS-BP 23,24, RegulomeDB 25, UNIProbe 26 и 27 Джаспер. После того, как кандидат ТФ определены, эти прогнозы могут быть специально протестированы с использованием антител против этих ТФ (EMSA-supershifts и Dapa-вестерны). EMSA-supershift включает добавление антитела к TF специфичные к ядерной лизата и олиго. Положительный результат в EMSA-supershift является магнезииesented как дальнейший сдвиг в полосе EMSA или потери полосы (обзор в ссылке 28). В дополнительном Dapa, 5'-биотинилированные олиго дуплекс, содержащий вариант и 20 пар оснований нуклеотидов фланговый инкубируют с ядерными лизата из соответствующего типа (ов) клеток, чтобы захватить любые ядерные факторы, специфически связывающих олигонуклеотидов. Фактор-комплекс олиго дуплексной ядерная скованной стрептавидином микрогранулы в магнитном колонке. Связанные ядерные факторы собираются непосредственно через элюирования 29,48. Связующие предсказания затем могут быть оценены с помощью Вестерн-блоттинга с использованием антител, специфичных к белку. В тех случаях, когда нет никаких очевидных предсказаний, или слишком много прогнозов, то элюции из вариантов отжимания экспериментов Dapa могут быть отправлены в активную зону протеомики для выявления кандидатов ТФ с использованием масс-спектрометрии, которые впоследствии могут быть проверены с помощью этих ранее описанных методы.

В оставшейся части статьи обе, подробный протокол для EMSA и Dapa анализа генетических вариантов предусмотрена.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

Although advances in sequencing and genotyping technologies have greatly enhanced our capacity to identify genetic variants associated with disease, our ability to understand the functional mechanisms impacted by these variants is lagging. A major source of the problem is that many disease-associated variants are located in n on-coding regions of the genome, which likely affect harder-to-predict mechanisms controlling gene expression. Here, we present a protocol based on the EMSA and DAPA techniques, valuable molecular t…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank Erin Zoller, Jessica Bene, and Lindsey Hays for input and direction in protocol development. MTW was supported in part by NIH R21 HG008186 and a Trustee Award grant from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. ZHP was supported in part by T32 GM063483-13.

Materials

| Custom DNA Oligonucleotides | Integrated DNA Technologies | http://www.idtdna.com/site/order/oligoentry | |

| Potassium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP366-500 | KCl, for CE buffer |

| HEPES (1M) | Fisher Scientific | 15630-080 | For CE and NE buffer |

| EDTA (0.5M), pH 8.0 | Life Technologies | R1021 | For CE, NE, and annealing buffer |

| Sodium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP358-1 | NaCl, for NE buffer |

| Tris-HCl (1M), pH 8.0 | Invitrogen | BP1756-100 | For annealing buffer |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (1X) | Fisher Scientific | MT21040CM | PBS, for cell wash |

| DL-Dithiothreitol solution (1M) | Sigma | 646563 | Reducing agent |

| PMSF | Thermo Scientific | 36978 | Protease Inhibitor |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Thermo Scientific | 78420 | Prevents dephosphorylation of TFs |

| Nonidet P-40 Substitute | IBI Scientific | IB01140 | NP-40, for nuclear extraction |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | For measuring protein concentration |

| Odyssey EMSA Buffer Kit | Licor | 829-07910 | Contains all necessary EMSA buffers |

| TBE Gels, 6%, 12 Wells | Invitrogen | EC6265BOX | For EMSA |

| TBE Buffer (10X) | Thermo Scientific | B52 | For EMSA |

| FactorFinder Starting Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-092-318 | Contains all necessary DAPA buffers |

| Licor Odyssey CLx | Licor | Recommended scanner for DAPA/EMSA | |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic | Gibco | 15240-062 | Contains 10,000 units/mL of penicillin, 10,000 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 25 µg/mL of Fungizone® Antimycotic |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Gibco | 26140-079 | FBS, for culture media |

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Gibco | 22400-071 | Contains L-glutamine and 25mM HEPES |

Referências

- Hindorff, L. A., et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (23), 9362-9367 (2009).

- Maurano, M. T., et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 337 (6099), 1190-1195 (2012).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 30 (11), 1095-1106 (2012).

- Paul, D. S., Soranzo, N., Beck, S. Functional interpretation of non-coding sequence variation: concepts and challenges. Bioessays. 36 (2), 191-199 (2014).

- Zhang, F., Lupski, J. R. Non-coding genetic variants in human disease. Hum Mol Genet. , (2015).

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 152 (6), 1237-1251 (2013).

- Slatkin, M. Linkage disequilibrium–understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat Rev Genet. 9 (6), 477-485 (2008).

- Bush, W. S., Moore, J. H. Chapter 11: Genome-wide association studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 8 (12), e1002822 (2012).

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 491 (7422), 56-65 (2012).

- Chang, C. C., et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 4, 7 (2015).

- Purcell, S., et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 81 (3), 559-575 (2007).

- ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 489 (7414), 57-74 (2012).

- Crawford, G. E., et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS). Genome Res. 16 (1), 123-131 (2006).

- Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y., Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 10 (12), 1213-1218 (2013).

- Giresi, P. G., Kim, J., McDaniell, R. M., Iyer, V. R., Lieb, J. D. FAIRE Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 17 (6), 877-885 (2007).

- Kent, W. J., et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12 (6), 996-1006 (2002).

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 518 (7539), 317-330 (2015).

- Martens, J. H., Stunnenberg, H. G. BLUEPRINT: mapping human blood cell epigenomes. Haematologica. 98 (10), 1487-1489 (2013).

- Liu, T., et al. Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biol. 12 (8), R83 (2011).

- Griffon, A., et al. Integrative analysis of public ChIP-seq experiments reveals a complex multi-cell regulatory landscape. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (4), e27 (2015).

- Staudt, L. M., et al. A lymphoid-specific protein binding to the octamer motif of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 323 (6089), 640-643 (1986).

- Singh, H., Sen, R., Baltimore, D., Sharp, P. A. A nuclear factor that binds to a conserved sequence motif in transcriptional control elements of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 319 (6049), 154-158 (1986).

- Weirauch, M. T., et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell. 158 (6), 1431-1443 (2014).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (Database issue), D930-D934 (2012).

- Boyle, A. P., et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1790-1797 (2012).

- Hume, M. A., Barrera, L. A., Gisselbrecht, S. S., Bulyk, M. L. UniPROBE, update 2015: new tools and content for the online database of protein-binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (Database issue), D117-D122 (2015).

- Mathelier, A., et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), 142-147 (2014).

- Smith, M. F., Delbary-Gossart, S. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA). Methods Mol Med. 50, 249-257 (2001).

- Franza, B. R., Josephs, S. F., Gilman, M. Z., Ryan, W., Clarkson, B. Characterization of cellular proteins recognizing the HIV enhancer using a microscale DNA-affinity precipitation assay. Nature. 330 (6146), 391-395 (1987).

- . BCA Protein Assay Kit: User Guide Available from: https://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/MAN0011430_Pierce_BCA_Protein_Asy_UG.pdf (2014)

- Wijeratne, A. B., et al. Phosphopeptide separation using radially aligned titania nanotubes on titanium wire. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 7 (21), 11155-11164 (2015).

- Silva, J. M., McMahon, M. The Fastest Western in Town: A Contemporary Twist on the Classic Western Blot Analysis. J. Vis. Exp. (84), (2014).

- Lu, X., et al. Lupus Risk Variant Increases pSTAT1 Binding and Decreases ETS1 Expression. Am J Hum Genet. 96 (5), 731-739 (2015).

- Ramana, C. V., Chatterjee-Kishore, M., Nguyen, H., Stark, G. R. Complex roles of Stat1 in regulating gene expression. Oncogene. 19 (21), 2619-2627 (2000).

- Fillebeen, C., Wilkinson, N., Pantopoulos, K. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for the Study of RNA-Protein Interactions: The IRE/IRP Example. J. Vis. Exp. (94), e52230 (2014).

- Heng, T. S., Painter, M. W. Immunological Genome Project, C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 9 (10), 1091-1094 (2008).

- Wu, C., et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 10 (11), R130 (2009).

- Wu, C., Macleod, I., Su, A. I. BioGPS and MyGene.info: organizing online, gene-centric information. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (Database issue), D561-D565 (2013).

- Wang, J., et al. Sequence features and chromatin structure around the genomic regions bound by 119 human transcription factors. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1798-1812 (2012).

- Holden, N. S., Tacon, C. E. Principles and problems of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 63 (1), 7-14 (2011).

- Xu, J., Liu, H., Park, J. S., Lan, Y., Jiang, R. Osr1 acts downstream of and interacts synergistically with Six2 to maintain nephron progenitor cells during kidney organogenesis. Development. 141 (7), 1442-1452 (2014).

- Yang, T. -. P., et al. Genevar: a database and Java application for the analysis and visualization of SNP-gene associations in eQTL studies. Bioinformatics. 26 (19), 2474-2476 (2010).

- Fort, A., et al. A liver enhancer in the fibrinogen gene cluster. Blood. 117 (1), 276-282 (2011).

- Solberg, N., Krauss, S. Luciferase assay to study the activity of a cloned promoter DNA fragment. Methods Mol Biol. 977, 65-78 (2013).

- Rahman, M., et al. A repressor element in the 5′-untranslated region of human Pax5 exon 1A. Gene. 263 (1-2), 59-66 (2001).

- Mali, P., et al. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science. 339 (6121), 823-826 (2013).