细胞分裂和扩张的运动学分析:量化增长和采样产业开发区的细胞学基础<em>玉米</em>叶

Summary

Quantifying cell division and expansion is of crucial importance to the understanding of whole-plant growth. Here, we present a protocol to calculate cellular parameters determining maize leaf growth rates and highlight the use of these data for investigating molecular growth regulatory mechanisms by directing developmental stage-specific sampling strategies.

Abstract

Growth analyses are often used in plant science to investigate contrasting genotypes and the effect of environmental conditions. The cellular aspect of these analyses is of crucial importance, because growth is driven by cell division and cell elongation. Kinematic analysis represents a methodology to quantify these two processes. Moreover, this technique is easy to use in non-specialized laboratories. Here, we present a protocol for performing a kinematic analysis in monocotyledonous maize (Zea mays) leaves. Two aspects are presented: (1) the quantification of cell division and expansion parameters, and (2) the determination of the location of the developmental zones. This could serve as a basis for sampling design and/or could be useful for data interpretation of biochemical and molecular measurements with high spatial resolution in the leaf growth zone. The growth zone of maize leaves is harvested during steady-state growth. Individual leaves are used for meristem length determination using a DAPI stain and cell-length profiles using DIC microscopy. The protocol is suited for emerged monocotyledonous leaves harvested during steady-state growth, with growth zones spanning at least several centimeters. To improve the understanding of plant growth regulation, data on growth and molecular studies must be combined. Therefore, an important advantage of kinematic analysis is the possibility to correlate changes at the molecular level to well-defined stages of cellular development. Furthermore, it allows for a more focused sampling of specified developmental stages, which is useful in case of limited budget or time.

Introduction

生长分析依赖于一组工具通常使用由植物科学家描述基因型确定生长的差异和/或表型响应于环境因素。它们包括全厂的大小和重量测量或器官和增长率的计算来探讨经济增长的内在机制。器官发育是细胞分裂和扩大在细胞水平确定。因此,包括在生长分析这两个过程的量化的关键是理解在整个器官1生长的差异。因此,关键是要具有适当的方法来确定细胞生长参数是相对容易由非专业的实验室使用。

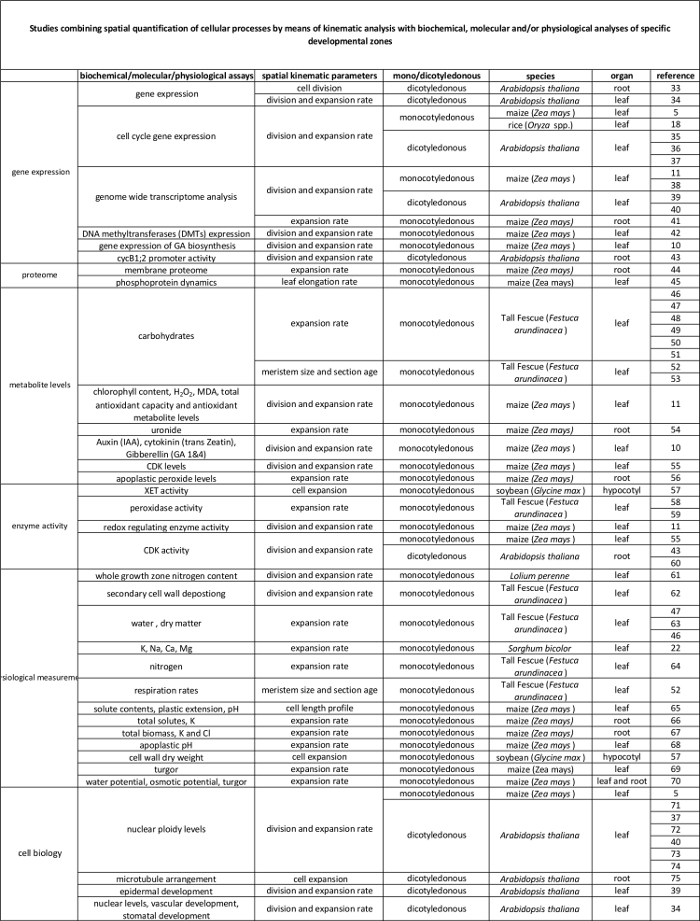

运动学分析已经被确立为一种方法提供的器官发育模型2发展的一个强大的框架。这项技术对线性系统进行了优化,如拟南芥根和单子叶叶子,也为非线性的系统中,例如双子叶叶片3。如今,这种方法被越来越多地用于研究如何遗传,激素,发育和环境因素影响细胞的分裂和各种器官的扩展( 表1)。此外,它也提供了一个框架,以细胞过程链接到他们的潜在生化,分子和生理规章( 表2),尽管限制可以通过器官大小和空间组织为需要更高量的植物材料的技术( 例如,代谢物施加测量,蛋白质组学, 等等 )。

单子叶叶子,如玉米( 玉蜀黍 )叶,表示其中的细胞从朝向尖叶的基部移动线性系统,通过分生组织和伸长区顺序地传递到到达成熟区。这使得它的增长4的空间格局定量研究的理想模式系统。此外,玉米叶有较大的增长区域(分生组织和伸长区跨越几厘米5),并在其他组织层次的研究提供了可能性。这允许(假定)的监管机制控制细胞分裂和扩大,通过一系列的分子生物学技术,生理测量和细胞生物学的方法( 见表2)通过运动学分析定量调查。

在这里,我们提供了在单子叶树叶进行运动分析的协议。首先,我们将解释如何进行这两种细胞分裂和细胞伸长的正确分析,沿叶轴位置以及如何计算运动学参数的函数。其次,我们还显示如何可以用作用于取样设计的基础。在这里,我们讨论了两种情况:高分辨率的采样ð集中采样,从而提高了数据的解释和时间/钱储蓄,分别为。

表1.运动概述分析了细胞分裂和各种器官的扩张量化方法。

| 器官 | 参考 |

| 单子叶植物的叶子 | 16,20,21,22 |

| 根尖 | 2,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 |

| 双子叶植物的叶子 | 21,30,31 |

| 拍摄顶端分生组织 | 32 |

表1.运动概述分析了细胞分裂和各种器官的扩张量化方法。

<p class="jove_content" fo:keep-together.within页="“1”">

表2.由运动分析来在分子水平上的调控量化细胞过程之间的链接。参考资料细胞过程的量化链接到来自于不同物种和器官生物化学和分子分析结果的各种研究。木聚糖endotransglucosylase(XET),丙二醛(MDA),细胞周期蛋白依赖性激酶(CDK)。 请点击这里查看此表的放大版本。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

在玉米叶片完整运动学分析,使叶片生长的细胞基础的决心,并允许有效采样战略的设计。虽然该协议是相对简单的,一些谨慎以下述关键步骤,建议:(1)它不破坏分生组织分离年轻的,封闭的叶(步骤2.3)中,由于分生组织长度判定(步骤3)是重要的,需要的完整分生组织到场。事先可能需要一些练习。 (2)分生长度确定是基于的核分裂解释。因此,我们建议,一个实验中,同一个人,由…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

这项工作是由来自安特卫普大学VA一个博士研究生奖学金的支持;从法兰德斯科学基金会(FWO,11ZI916N),以KS博士奖学金;从FWO(G0D0514N)项目赠款;协调一致的研究活动(GOA)研究经费,从安特卫普大学的研究委员会“叶形态的系统生物学方法”;和校际景点波兰人(IUAP VII / 29,MARS),“玉米和拟南芥幼苗和根生长”,从比利时联邦科学政策办公室(BELSPO),以GTSB韩Asard,Bulelani L. Sizani和滨田AbdElgawad都促使视频。

Materials

| Pots | Any | Any | We use pots with the following measueres, but can be different depending on the treatment/study : bottom diameter: 11cm, opening diameter: 15 cm, height: 12 cm. We grow one maize plant per pot. |

| Planting substrate | Any | Any | We use potting medium (Jiffy, The Netherlands), but other substrates can be used, depending on treatment/study. |

| Ruler | Any | Any | An extension ruler that covers at least 1,5 meters is needed to measure the final leaf length of the plants. |

| Seeds | Any | NA | Seeds can be ordered from a breeder. |

| Scalpel | Any | Any | The scalpel is used during leaf harvesting to detach the leaf of interest from its surrounding leaves and right after harvesting to cut a proper sample for cell length and meristem length measurements. |

| 15 ml falcon tubes | Any | Any | The 15 ml falcon tubes are used for storing samples used for cell length measurements during sample clearing with absolute ethanol and lactic acid. |

| Eppendorf tubes | Any | Any | The eppendorf tubes are used for storing samples used for meristem length measurements in ethanol:acetic acid 3:1 (v:v) solution. |

| Gloves | Any | Any | Latex gloves, which protect against corrosive reagents. |

| Acetic acid | Any | Any | CAUTION: Corrosive to metals, category 1 Skin corrosion, categories 1A,1B,1C Serious eye damage, category 1; Flammable liquids, categories 1,2,3 |

| Absolute ethanol | Any | Any | CAUTION: Hazardous in case of skin contact (irritant), of eye contact (irritant), of inhalation. Slightly hazardous in case of skin contact (permeator), of ingestion |

| Lactic acid >98% | Any | Any | CAUTION: Corrosive to metals, category 1 Skin corrosion, categories 1A,1B,1C Serious eye damage, category 1 |

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) | Any | Any | |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Any | Any | CAUTION: Acute toxicity (oral, dermal, inhalation), category 4 Skin irritation, category 2 Eye irritation, category 2 Skin sensitisation, category 1 Specific Target Organ Toxicity – Single exposure, category 3 |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) | Any | Any | This material can be an irritant, contact with eyes and skin should be avoided. Inhalation of dust may be irritating to the respiratory tract. |

| 4′,6-Diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) | Any | Any | Cell permeable fluorescent minor groove-binding probe for DNA. Causes skin irritation. May cause an allergic skin reaction. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Ice | Any | NA | The DAPI solution has to be kept on ice. |

| Fluorescent microscope | AxioScope A1, Axiocam ICm1 from Zeiss or other | Any fluorescent microscope can be used for determining meristem length. | |

| Microscopic slide | Any | Any | |

| Cover glass | Any | Any | |

| Tweezers | Any | Any | Tweezers are needed for unfolding the rolled maize leaf right after harvesting in order to cut a proper sample for cell length and meristem length measurements. |

| Image-analysis software | Axiovision (Release 4.8) from Zeiss | NA | The software can be downloaded at: http://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en_de/downloads/axiovision.html. Other softwares such as ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) could be used as well. |

| Microscope equipped with DIC | AxioScope A1, Axiocam ICm1 from Zeiss or other | Any microscope, equipped with differential interference contrast (DIC) can be used to measure cell lengths. | |

| R statistical analysis software | R Foundation for Statistical Computing | NA | Open source; Could be downloaded at https://www.r-project.org/ |

| R script | NA | NA | We use the kernel smoothing function locpoly of the Kern Smooth package (Wand MP, Jones MC. Kernel Smoothing: Chapman & Hall/CRC (1995)). The script is available for Mac and Windows upon inquire with the corresponding author. We have versions for Mac and Windows. |

Referências

- Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S. Quantitative analyses of cell division in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 60, 963-979 (2006).

- Silk, W. K., Erickson, R. O. Kinematics of Plant-Growth. J. Theor. Biol. 76, 481-501 (1979).

- Rymen, B., Coppens, F., Dhondt, S., Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S., Hennig, L., Köhler, C. Kinematic Analysis of Cell Division and Expansion. Plant Developmental Biology. , (2010).

- Avramova, V., Sprangers, K., Beemster, G. T. S. The Maize Leaf: Another Perspective on Growth Regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 787-797 (2015).

- Rymen, B., et al. Cold nights impair leaf growth and cell cycle progression in maize through transcriptional changes of cell cycle genes. Plant Physiol. 143, 1429-1438 (2007).

- Muller, B., Reymond, M., Tardieu, F. The elongation rate at the base of a maize leaf shows an invariant pattern during both the steady-state elongation and the establishment of the elongation zone. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1259-1268 (2001).

- Beemster, G. T. S., Masle, J., Williamson, R. E., Farquhar, G. D. Effects of soil resistance to root penetration on leaf expansion in wheat (Triticum aestivum L): Kinematic analysis of leaf elongation. J. Exp. Bot. 47, 1663-1678 (1996).

- Bernstein, N., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Development of Sorghum Leaves under Conditions of Nacl Stress – Spatial and Temporal Aspects of Leaf Growth-Inhibition. Planta. 191, 433-439 (1993).

- Sylvester, A. W., Smith, L. G., Bennetzen, J. L., Hake, S. C. Cell Biology of Maize Leaf Development. Handbook of maize: It’s Biology. , (2009).

- Nelissen, H., et al. A Local Maximum in Gibberellin Levels Regulates Maize Leaf Growth by Spatial Control of Cell Division. Curr. Biol. 22, 1183-1187 (2012).

- Avramova, V., et al. Drought Induces Distinct Growth Response, Protection, and Recovery Mechanisms in the Maize Leaf Growth Zone. Plant Physiol. 169, 1382-1396 (2015).

- Picaud, J. C., et al. Total malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations as a marker of lipid peroxidation in all-in-one parenteral nutrition admixtures (APA) used in newborn infants. Pediatr. Res. 53, 406 (2003).

- Basu, P., Pal, A., Lynch, J. P., Brown, K. M. A novel image-analysis technique for kinematic study of growth and curvature. Plant Physiol. 145, 305-316 (2007).

- Vander Weele, C. M., et al. A new algorithm for computational image analysis of deformable motion at high spatial and temporal resolution applied to root growth. Roughly uniform elongation in the meristem and also, after an abrupt acceleration, in the elongation zone. Plant Physiol. 132, 1138-1148 (2003).

- Nelissen, H., Rymen, B., Coppens, F., Dhondt, S., Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S., DeSmet, I. . Plant Organogenesis. , (2013).

- Ben-Haj-Salah, H., Tardieu, F. Temperature Affects Expansion Rate of Maize Leaves without Change in Spatial-Distribution of Cell Length – Analysis of the Coordination between Cell-Division and Cell Expansion. Plant Physiol. 109, 861-870 (1995).

- Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S., Bultynck, L., Lambers, H. Can meristematic activity determine variation in leaf size and elongation rate among four Poa species? A kinematic study. Plant Physiol. 124, 845-855 (2000).

- Pettko-Szandtner, A., et al. Core cell cycle regulatory genes in rice and their expression profiles across the growth zone of the leaf. J. Plant Res. 128, 953-974 (2015).

- Poorter, H., Remkes, C. Leaf-Area Ratio and Net Assimilation Rate of 24 Wild-Species Differing in Relative Growth-Rate. Oecologia. 83, 553-559 (1990).

- Macadam, J. W., Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Effects of Nitrogen on Mesophyll Cell-Division and Epidermal-Cell Elongation in Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 89, 549-556 (1989).

- Tardieu, F., Granier, C. Quantitative analysis of cell division in leaves: methods, developmental patterns and effects of environmental conditions. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 555-567 (2000).

- Bernstein, N., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Development of Sorghum Leaves under Conditions of Nacl Stress – Possible Role of Some Mineral Elements in Growth-Inhibition. Planta. 196, 699-705 (1995).

- Erickson, R. O., Sax, K. B. Rates of Cell-Division and Cell Elongation in the Growth of the Primary Root of Zea-Mays. P. Am. Philos. Soc. 100, 499-514 (1956).

- Beemster, G. T. S., Baskin, T. I. Analysis of cell division and elongation underlying the developmental acceleration of root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 116, 1515-1526 (1998).

- Goodwin, R. H., Stepka, W. Growth and differentiation in the root tip of Phleum pratense. Am. J. Bot. 32, 36-46 (1945).

- Hejnowicz, Z. Growth and Cell Division in the Apical Meristem of Wheat Roots. Physiologia Plantarum. 12, 124-138 (1959).

- Gandar, P. W. Growth in Root Apices .1. The Kinematic Description of Growth. Bot. Gaz. 144, 1-10 (1983).

- Baskin, T. I., Cork, A., Williamson, R. E., Gorst, J. R. Stunted-Plant-1, a Gene Required for Expansion in Rapidly Elongating but Not in Dividing Cells and Mediating Root-Growth Responses to Applied Cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 107, 233-243 (1995).

- Sacks, M. M., Silk, W. K., Burman, P. Effect of water stress on cortical cell division rates within the apical meristem of primary roots of maize. Plant Physiol. 114, 519-527 (1997).

- Granier, C., Tardieu, F. Spatial and temporal analyses of expansion and cell cycle in sunflower leaves – A common pattern of development for all zones of a leaf and different leaves of a plant. Plant Physiol. 116, 991-1001 (1998).

- De Veylder, L., et al. Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 13, 1653-1667 (2001).

- Kwiatkowska, D. Surface growth at the reproductive shoot apex of Arabidopsis thaliana pin-formed 1 and wild type. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1021-1032 (2004).

- Kutschmar, A., et al. PSK-alpha promotes root growth in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 181, 820-831 (2009).

- Vanneste, S., et al. Plant CYCA2s are G2/M regulators that are transcriptionally repressed during differentiation. Embo J. 30, 3430-3441 (2011).

- Eloy, N. B., et al. Functional Analysis of the anaphase-Promoting Complex Subunit 10. Plant J. 68, 553-563 (2011).

- Eloy, N. B., et al. SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome regulator is involved in early development and A-type cyclin stabilization. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 13853-13858 (2012).

- Dhondt, S., et al. SHORT-ROOT and SCARECROW Regulate Leaf Growth in Arabidopsis by Stimulating S-Phase Progression of the Cell Cycle. Plant Physiol. 154, 1183-1195 (2010).

- Baute, J., et al. Correlation analysis of the transcriptome of growing leaves with mature leaf parameters in a maize RIL population. Genome Biol. 16, (2015).

- Andriankaja, M., et al. Exit from Proliferation during Leaf Development in Arabidopsis thaliana: A Not-So-Gradual Process. Dev. Cell. 22, 64-78 (2012).

- Beemster, G. T. S., et al. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression profiles associated with cell cycle transitions in growing organs of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138, 734-743 (2005).

- Spollen, W. G., et al. Spatial distribution of transcript changes in the maize primary root elongation zone at low water potential. Bmc Plant Biol. 8, (2008).

- Candaele, J., et al. Differential Methylation during Maize Leaf Growth Targets Developmentally Regulated Genes. Plant Physiol. 164, 1350-1364 (2014).

- West, G., Inze, D., Beemster, G. T. S. Cell cycle modulation in the response of the primary root of Arabidopsis to salt stress. Plant Physiol. 135, 1050-1058 (2004).

- Zhang, Z., Voothuluru, P., Yamaguchi, M., Sharp, R. E., Peck, S. C. Developmental distribution of the plasma membrane-enriched proteome in the maize primary root growth zone. Front. Plant Sci. 4, (2013).

- Bonhomme, L., Valot, B., Tardieu, F., Zivy, M. Phosphoproteome Dynamics Upon Changes in Plant Water Status Reveal Early Events Associated With Rapid Growth Adjustment in Maize Leaves. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 11, 957-972 (2012).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Growth-Rates and Assimilate Partitioning in the Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades at High and Low Irradiance. Plant Physiol. 90, 1201-1206 (1989).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J., Spollen, W. G. Diurnal Growth of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades .2. Dry-Matter Partitioning and Carbohydrate-Metabolism in the Elongation Zone and Adjacent Expanded Tissue. Plant Physiol. 86, 1077-1083 (1988).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Growth-Rates and Carbohydrate Fluxes within the Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 85, 548-553 (1987).

- Vassey, T. L., Shnyder, H. S., Spollen, W. G., Nelson, C. J. Cellular Characterisation and Fructan Profiles in Expanding Tall Fescue. Curr. T. Pl. B. 4, 227-229 (1985).

- Allard, G., Nelson, C. J. Photosynthate Partitioning in Basal Zones of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 95, 663-668 (1991).

- Spollen, W. G., Nelson, C. J. Response of Fructan to Water-Deficit in Growing Leaves of Tall Fescue. Plant Physiol. 106, 329-336 (1994).

- Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Carbohydrate-Metabolism in Leaf Meristems of Tall Fescue .1. Relationship to Genetically Altered Leaf Elongation Rates. Plant Physiol. 74, 590-594 (1984).

- Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Carbohydrate-Metabolism in Leaf Meristems of Tall Fescue .2. Relationship to Leaf Elongation Rates Modified by Nitrogen-Fertilization. Plant Physiol. 74, 595-600 (1984).

- Silk, W. K., Walker, R. C., Labavitch, J. Uronide Deposition Rates in the Primary Root of Zea-Mays. Plant Physiol. 74, 721-726 (1984).

- Granier, C., Inze, D., Tardieu, F. Spatial distribution of cell division rate can be deduced from that of p34(cdc2) kinase activity in maize leaves grown at contrasting temperatures and soil water conditions. Plant Physiol. 124, 1393-1402 (2000).

- Voothuluru, P., Sharp, R. E. Apoplastic hydrogen peroxide in the growth zone of the maize primary root under water stress.1. Increased levels are specific to the apical region of growth maintenance. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1223-1233 (2012).

- Wu, Y. J., Jeong, B. R., Fry, S. C., Boyer, J. S. Change in XET activities, cell wall extensibility and hypocotyl elongation of soybean seedlings at low water potential. Planta. 220, 593-601 (2005).

- Macadam, J. W., Nelson, C. J., Sharp, R. E. Peroxidase-Activity in the Leaf Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue .1. Spatial-Distribution of Ionically Bound Peroxidase-Activity in Genotypes Differing in Length of the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 99, 872-878 (1992).

- Macadam, J. W., Sharp, R. E., Nelson, C. J. Peroxidase-Activity in the Leaf Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue .2. Spatial-Distribution of Apoplastic Peroxidase-Activity in Genotypes Differing in Length of the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 99, 879-885 (1992).

- Beemster, G. T. S., De Vusser, K., De Tavernier, E., De Bock, K., Inze, D. Variation in growth rate between Arabidopsis ecotypes is correlated with cell division and A-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Plant Physiol. 129, 854-864 (2002).

- Kavanova, M., Lattanzi, F. A., Schnyder, H. Nitrogen deficiency inhibits leaf blade growth in Lolium perenne by increasing cell cycle duration and decreasing mitotic and post-mitotic growth rates. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 727-737 (2008).

- Macadam, J. W., Nelson, C. J. Secondary cell wall deposition causes radial growth of fibre cells in the maturation zone of elongating tall fescue leaf blades. Ann. Bot-London. 89, 89-96 (2002).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Diurnal Growth of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades .1. Spatial-Distribution of Growth, Deposition of Water, and Assimilate Import in the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 86, 1070-1076 (1988).

- Gastal, F., Nelson, C. J. Nitrogen Use within the Growing Leaf Blade of Tall Fescue. Plant Physiol. 105, 191-197 (1994).

- Vanvolkenburgh, E., Boyer, J. S. Inhibitory Effects of Water Deficit on Maize Leaf Elongation. Plant Physiol. 77, 190-194 (1985).

- Silk, W. K., Hsiao, T. C., Diedenhofen, U., Matson, C. Spatial Distributions of Potassium, Solutes, and Their Deposition Rates in the Growth Zone of the Primary Corn Root. Plant Physiol. 82, 853-858 (1986).

- Meiri, A., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Deposition of Inorganic Nutrient Elements in Developing Leaves of Zea-Mays L. Plant Physiol. 99, 972-978 (1992).

- Neves-Piestun, B. G., Bernstein, N. Salinity-induced inhibition of leaf elongation in maize is not mediated by changes in cell wall acidification capacity. Plant Physiol. 125, 1419-1428 (2001).

- Bouchabke, O., Tardieu, F., Simonneau, T. Leaf growth and turgor in growing cells of maize (Zea mays L.) respond to evaporative demand under moderate irrigation but not in water-saturated soil. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 1138-1148 (2006).

- Westgate, M. E., Boyer, J. S. Transpiration-Induced and Growth-Induced Water Potentials in Maize. Plant Physiol. 74, 882-889 (1984).

- Horiguchi, G., Gonzalez, N., Beemster, G. T. S., Inze, D., Tsukaya, H. Impact of segmental chromosomal duplications on leaf size in the grandifolia-D mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 60, 122-133 (2009).

- Fleury, D., et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana homolog of yeast BRE1 has a function in cell cycle regulation during early leaf and root growth. Plant Cell. 19, 417-432 (2007).

- Vlieghe, K., et al. The DP-E2F-like gene DEL1 controls the endocycle in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 15, 59-63 (2005).

- Boudolf, V., et al. The plant-specific cyclin-dependent kinase CDKB1;1 and transcription factor E2Fa-DPa control the balance of mitotically dividing and endoreduplicating cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 16, 2683-2692 (2004).

- Baskin, T. I., Beemster, G. T. S., Judy-March, J. E., Marga, F. Disorganization of cortical microtubules stimulates tangential expansion and reduces the uniformity of cellulose microfibril alignment among cells in the root of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135, 2279-2290 (2004).