体外孤蜂饲养: 一种评估幼虫危险因素的工具

Summary

在开花植物上喷洒杀菌剂可以使孤蜂接触到高浓度的花粉传播杀菌剂残留物。本研究以实验为基础, 结合体外饲养蜂幼虫, 探讨了寄主和非寄主植物对杀菌剂处理花粉的影响。

Abstract

虽然孤蜂为野生和被管理的农作物提供重要的授粉服务, 但在农药管制研究中, 这种富含物种的群体已基本被忽视。如果喷雾发生在或靠近寄主植物的情况下, 当蜜蜂收集花粉来供应巢时, 接触杀菌剂残留物的风险可能会特别高。对于从一组植物中摄取花粉的蜂物种 (oligolecty), 不能利用非寄主植物的花粉可以增加其与杀菌剂相关毒性的危险因素。本手稿描述了用于成功后方 oligolectic 梅森蜜蜂,蜂 ribifloris严格 lato, 从鸡蛋到 prepupal 阶段在细胞培养板的标准化实验室条件下的协议。在体外饲养的蜜蜂随后被用来研究杀菌剂暴露和花粉来源对蜜蜂健康的影响。以 2 x 2 全交叉因子设计为基础, 研究了杀菌剂暴露和花粉源对幼虫体质的主要影响和交互作用, prepupal 生物量、幼虫发育时间和存活率进行量化。这种技术的一个主要优点是, 使用体外饲养的蜜蜂可以减少自然背景的变异性, 同时也能同时操作多个实验参数。描述的协议提供了一个通用的工具, 假设测试涉及一系列影响蜜蜂健康的因素。为了使保护工作取得重大的、持久的成功, 对导致蜜蜂下降的生理和环境因素的复杂相互作用的这种洞察将被证明是至关重要的。

Introduction

鉴于它们作为昆虫传粉者的主导群体1, 全球蜜蜂种群的损失对粮食安全和生态系统稳定性构成威胁2、3、4、5、6 ,7。管理和野生蜜蜂种群的下降趋势归因于几个共同的危险因素, 包括生境分裂、新出现的寄生虫和病原体、遗传多样性的丧失以及入侵物种的引进3 ,4,7,8,9,10,11,12。特别是, 杀虫剂的使用急剧增加 (例如, neonicotinoids) 与蜜蜂13、14、15之间的有害影响直接相关。一些研究表明, neonicotinoids 和麦角甾醇生物合成抑制 (EBI) 杀菌剂之间的协同作用可能导致高死亡率横跨多蜂种类16,17,18,19,20,21,22. 然而, 长期以来被认为是 “蜜蜂安全” 的杀菌剂继续喷洒在开花作物上, 但没有对23进行过多的审查。觅食蜜蜂已被记录下来, 例行带回花粉负荷污染的杀菌剂残留物24,25,26。这种杀菌剂 ladenpollen 的消费量会导致幼虫蜂27、28、29、30之间的高死亡率, 以及成年蜜蜂中的一组亚致死效应16,31,32,33,34. 最近的一项研究表明, 杀菌剂可能会通过改变蜂巢储存的花粉中的微生物群落来造成蜜蜂的损失, 从而扰乱蜜蜂和花粉传播的微生物之间的关键共生35。

虽然孤蜂对几种野生和农业植物的授粉至关重要,36、37、38, 但这种不同的传粉群体在农药监测研究中受到的关注较少。一个成年的独居女性的巢包含5-10 个封闭的巢室, 每个都有一个有限质量的母系收集的花粉和花蜜, 和一个单一的鸡蛋39。孵化后, 幼虫依赖于分配的花粉提供, 和相关的花粉传播的微生物群获得足够的营养40,41。因为他们缺乏社会生活方式的好处, 孤独的蜜蜂可能更容易受到杀虫剂的照射42。例如, 虽然在喷洒后的社会蜜蜂的赤字可能会得到工人和新出现的巢的一些扩大, 一个单一的成年单身女性的死亡结束所有的生殖活动43。这种易感性的差异突出表明需要在生态研究中纳入不同的蜜蜂分类, 以确保对被管理和野生蜜蜂有足够的保护。然而, 除了少数研究, 对杀菌剂暴露的影响的调查主要集中在社会蜜蜂18,23,32,44,45 ,46,47,48,49。

属于蜂属的孤蜂 (图 1) 已被全世界用作多种重要水果和坚果作物的有效传粉者, 39,50,51,53,53. 与其他被管理的授粉小组 24,54,55,56,57,58, 成年蜂蜜蜂通常暴露于杀菌剂喷洒在开花作物44。在最近喷洒的农作物上觅食的成年雌性可能会收集和储存他们的巢室与杀菌剂的花粉, 后来形成了唯一的饮食发育幼虫。食用受污染的花粉的规定随后可将幼虫暴露于杀菌剂残留物42。在 oligolectic 物种中, 接触的风险可能较高, 仅在少数几个密切相关的寄主植物上觅食59、60、61。例如, 某些 megachilid 蜜蜂似乎优先饲料低品质的菊科花粉, 作为减少寄生62的一种手段。然而, 杀菌剂对 oligolectic 孤蜂幼虫适应性的影响程度尚未得到实证量化。本研究的目的是制定一个协议, 以检验杀菌剂暴露和花粉源对体外饲养孤蜂的适应性的主要和交互作用。为了调查, ribifloris lato (广义) 的卵可以在商业上获得 (材料表)。这个人口是理想的, 因为它作为一个土生土长的授粉的重要性, 并且它强烈偏爱花蜜丰富的十大功劳 aquifolium (俄勒冈葡萄) 发现在区域53,63,64(图 2)。

图1。一张成人蜂 ribifloris的高分辨率照片。照片信贷, 美国农业部研究昆虫学家吉姆. 甘蔗,请点击这里查看这个数字的更大版本.

图2。芦苇蜂 ribifloris (广义)的嵌套芦苇, 在前景中嵌套雌性. 芦苇的室隔断和端子插头是由咀嚼叶构造的。照片信用 NativeBees.com 先生,请点击这里查看这个数字的大版本.

本研究的第一个目的是评估食用杀菌剂处理花粉对幼虫体质的影响 (以发育时间和 prepupal 生物量计算)。虽然接触到普遍应用的杀菌剂丙环唑已与成年蜜蜂之间的死亡率增加23,24,32,44,45, 54、55、56、57、58、65、66、67, 对蜜蜂幼虫的影响较小知道。本研究的第二个目的是评估食用非寄主花粉对幼虫体质的影响。以往的研究表明, oligolectic 蜜蜂的幼虫在被迫食用非寄主花粉68时未能发育。这种结果可能归因于蜜蜂生理学69、花粉生物化学70和与天然花粉有关的有益菌群的变化 (71)。本研究的第三个目的是评价杀菌剂处理和日粮花粉对幼体健康的交互作用。

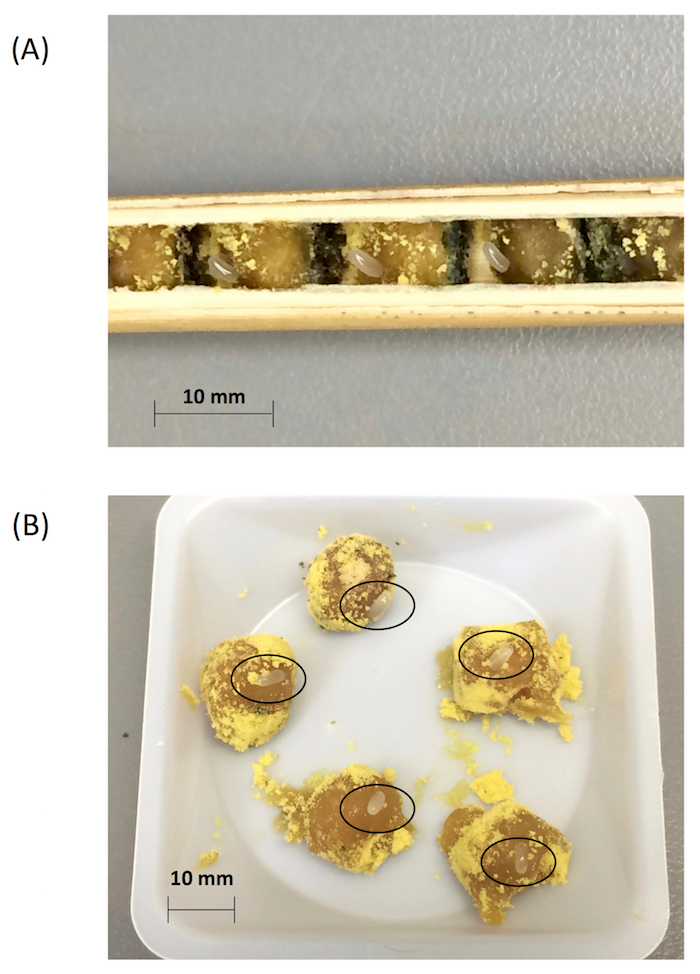

众所周知, 许多生物学特性包括产妇体型、调配率、觅食策略和花粉量72、73、74、75都影响了孤蜂幼虫的适应性。这些因素可以在芦苇之间引入显著的变异性, 这在评估幼虫的健康状况时, 对发展防御性实验设计构成了挑战。此外, 鉴于幼虫的发育发生在密封的筑巢芦苇内, 这种变异对后代的影响很难想象和量化而不使用非致命技术 (图 3)。为了克服这一挑战, 本研究中的所有假说都是使用饲养在巢状芦苇外的幼虫来测试的。实验设计代表一个完全交叉的 2 x 2 阶乘设置, 每个因素由2级组成;因子 1: 杀菌剂暴露 (杀菌剂;无杀菌剂);因子 2: 花粉源 (寄主花粉, 非寄主花粉)。在受控实验室条件下, 蜜蜂在无菌多井细胞培养板中由卵向 prepupal 阶段培养。每个井都有一个标准的花粉供应量和一个鸡蛋。孵化后, 幼虫在井内分配的花粉上进食, 完成幼虫发育, 并启动蛹。过去的研究表明, 在这种人工饲养环境中所饲养的蜜蜂中, 无法解释的死亡率低于野外49、76所遇到的。在体外饲养的蜜蜂的使用比基于田间的研究有几个优点: 1) 它最大限度地减少自然变异性和不受控制因素的混杂效应, 通常与实地研究相关;2) 它允许在治疗组中同时测试每个感兴趣因素的多层次操作;3) 复制的次数可以预先确定, 每个复制的实验因素可以单独操作;4) 幼虫响应变量可在不干扰相邻幼虫的情况下, 独立地进行可视化和记录;5) 可以修改该协议, 以适应涉及多个因素和响应变量的更复杂的实验设计。

图3。蜂 ribifloris (广义)天然嵌套芦苇中的含量.关闭(a)解剖的芦苇, 显示个别的房间, 花粉的规定和分区, (B)新鲜收获的花粉规定, 和相关的鸡蛋 (用黑色圆圈表示)。请单击此处查看此图的较大版本.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

在实验室条件下, 在其天然筑巢芦苇外饲养蜜蜂, 可以测试与幼虫体质有关的多个假说。如果不明因素继续导致蜜蜂死亡, 使用体外实验进行的风险评估研究可以帮助确定潜在的威胁, 并告知该物种丰富的野生传粉者群的管理做法12 ,38,49,76,81,82?…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

作者感谢克拉克和蒂姆克罗提供蜂筑巢芦苇, 梅瑞狄斯 Nesbitt 和莫莉比德韦尔协助在实验室, Drs. 卡梅伦·柯里, Christelle Guédot, 特里格里斯沃尔德, 迈克尔 Branstetter 和三匿名评论家为他们有用的评论, 改进了手稿。这项工作得到了农业部-农业研究服务划拨资金 (目前研究信息系统 #3655-21220-001)、威斯康星农业、贸易和消费者保护部 (#197199)、国家科学基金会 (根据格兰特号DEB-1442148), 能源部大湖生物能源研究中心 (能源部的科学 DE-FC02-07ER64494)。

Materials

| eggs of O. ribifloris sensu lato (s.l.) | Kaysville, Davis County, Utah, USA | ||

| Osmia reeds | Nativebees.com | NA | Freshly plugged reeds |

| Dissection set | VWR | 89259-964 | Sterilize before use |

| Long Nose Pliers | Husky | 1006 | |

| 6 well culture plates | VWR | 10062-892 | Sterile sealed |

| 48 well culture plates | VWR | 10062-898 | Sterile sealed |

| Petri dishes | VWR | 25373100 | Sterile sealed |

| Square Weighing Boats | VWR | 10770-448 | |

| Camel Hair Brush | Bioquip | 1153A | |

| Tin capsules | EA Consumables | D1021 | Sterilize before use |

| Sucrose | VWR | 470302-808 | |

| Propiconazole 14.3 | Quali-Ppro | 60207-90-1 | Propiconazole 14.3% |

| Honey bee pollen | Bee energised | 897098001244 | Untreated, natural, raw pollen |

| Microbalance | VWR | 10204-990 | |

| Pulverisette | LAB SYNERGY INC. | 30334913 | |

| Wooden sticks | VWR | 470146908 | Sterilize before use |

| Sealing tape | VWR | 89097-912 | |

| Microscope | VWR | 89403-384 | |

| Planting tray | VWR | 470150-632 | |

| Ethanol | VWR | BDH1158-4LP | |

| Centrifuge tube | VWR | 21008936 | |

| Microsyringe | Cole-Palmer | UX-07940-07 | |

| Rubber tweezer | Amazon | B0135HWPN4 | |

| Syringe needles | VWR | 89219-334 | |

| Freeze drier | Labcono | LFZ-1L | |

| Statistical software | SPSS | Version 21.0 |

Referências

- Klein, A. -. M., et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. P Roy Soc Lond B Bio. 274 (1608), 303-313 (2007).

- Biesmeijer, J. C. J., et al. Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science. 313 (5785), 351-354 (2006).

- Potts, S. G., Biesmeijer, J. C., Kremen, C., Neumann, P., Schweiger, O., Kunin, W. E. Global pollinator declines: Trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol. 25 (6), 345-353 (2010).

- Cameron, S. A., et al. Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 108 (2), 662-667 (2011).

- Gallai, N., Salles, J. M., Settele, J., Vaissière, B. E. Economic valuation of the vunerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecol Econ. 68 (3), 810-821 (2009).

- Fontaine, C., Dajoz, I., Meriguet, J., Loreau, M. Functional diversity of plant-pollinator interaction webs enhances the persistence of plant communities. Plos Biol. 4 (1), 0129-0135 (2006).

- Kluser, S., Peduzzi, P. . Global pollinator decline: a literature review. , (2007).

- Brown, M. J. F., Paxton, R. J. The conservation of bees: a global perspective. Apidologie. 40 (3), (2009).

- Lebuhn, G., et al. Detecting insect pollinator declines on regional and global scales. Conserv Biol. 27 (1), (2013).

- Vanengelsdorp, D., Meixner, M. D. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. J Invertebr Pathol. , S80-S95 (2010).

- Pettis, J. S., Delaplane, K. S. Coordinated responses to honey bee decline in the USA. Apidologie. 41 (3), 256-263 (2010).

- Sandrock, C., Tanadini, L. G., Pettis, J. S., Biesmeijer, J. C., Potts, S. G., Neumann, P. Sublethal neonicotinoid insecticide exposure reduces solitary bee reproductive success. Agr Forest Entomol. 16 (2), (2014).

- Van der Sluijs, J. P., Simon-Delso, N., Goulson, D., Maxim, L., Bonmatin, J. M., Belzunces, L. P. Neonicotinoids, bee disorders and the sustainability of pollinator services. Curr Opin Env Sust. 5 (3), (2013).

- Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C., Rotheray, E. L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science. 347 (6229), (2015).

- Johnson, R. M., Ellis, M. D., Mullin, C. A., Frazier, M. Pesticides and honey bee toxicity – USA. Apidologie. 41 (3), (2010).

- Iwasa, T., Motoyama, N., Ambrose, J. T., Roe, R. M. Mechanism for the differential toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Crop Protection. 23 (5), 371-378 (2004).

- Glavan, G., Bozic, J. The synergy of xenobiotics in honey bee Apis mellifera: mechanisms and effects. Acta Biol. Slov. 56, 11-27 (2013).

- Biddinger, D. J., et al. Comparative toxicities and synergism of apple orchard pesticides to Apis mellifera (L.) and Osmia cornifrons (Radoszkowski). PLoS ONE. 8 (9), e72587 (2013).

- Thompson, H. M., Fryday, S. L., Harkin, S., Milner, S. Potential impacts of synergism in honeybees (Apis mellifera) of exposure to neonicotinoids and sprayed fungicides in crops. Apidologie. 45 (5), 545-553 (2014).

- Jansen, J. -. P., Lauvaux, S., Gruntowy, J., Denayer, J. Possible synergistic effects of fungicide-insecticide mixtures on beneficial arthropods. IOBC-WPRS Bulletin. 125, 28-35 (2017).

- Robinson, A., Hesketh, H., et al. Comparing bee species responses to chemical mixtures: Common response patterns?. PLoS ONE. 12 (6), (2017).

- Sgolastra, F., Medrzycki, P., et al. Synergistic mortality between a neonicotinoid insecticide and an ergosterol-biosynthesis-inhibiting fungicide in three bee species. Pest Management Science. 73 (6), 1236-1243 (2017).

- Ladurner, E., Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P., Maini, S. Assessing delayed and acute toxicity of five formulated fungicides to Osmia lignaria and Apis mellifera. Apidologie. 36 (3), 449-460 (2005).

- Mullin, C. A., et al. High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in North American apiaries: implications for honey bee health. PloS one. 5 (3), e9754 (2010).

- Pettis, J. S., Lichtenberg, E. M., Andree, M., Stitzinger, J., Rose, R., Vanengelsdorp, D. Crop pollination exposes honey bees to pesticides which alters their susceptibility to the gut pathogen Nosema ceranae. PloS one. 8 (7), e70182 (2013).

- David, A., et al. Widespread contamination of wildflower and bee-collected pollen with complex mixtures of neonicotinoids and fungicides commonly applied to crops. Environ Int. 88, 169-178 (2016).

- Zhu, W., Schmehl, D. R., Mullin, C. A., Frazier, J. L. Four common pesticides, their mixtures and a formulation solvent in the hive environment have high oral toxicity to honey bee larvae. PloS one. 9 (1), e77547 (2014).

- Simon-Delso, N., Martin, G. S., Bruneau, E., Minsart, L. A., Mouret, C., Hautier, L. Honeybee colony disorder in crop areas: The role of pesticides and viruses. PLoS ONE. 9 (7), (2014).

- Park, M. G., Blitzer, E. J., Gibbs, J., Losey, J. E., Danforth, B. N. Negative effects of pesticides on wild bee communities can be buffered by landscape context. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 282 (1809), 20150299-20150299 (2015).

- Bernauer, O. M., Gaines-Day, H. R., Steffan, S. A. Colonies of bumble bees (Bombus impatiens) produce fewer workers, less bee biomass, and have smaller mother queens following fungicide exposure. Insects. 6 (2), 478-488 (2015).

- Williamson, S. M., Wright, G. A. Exposure to multiple cholinergic pesticides impairs olfactory learning and memory in honeybees. J Exp Biol. 216 (10), 1799-1807 (2013).

- Artz, D. R., Pitts-Singer, T. L. Effects of fungicide and adjuvant sprays on nesting behavior in two managed solitary bees, Osmia lignaria and Megachile rotundata. PLoS ONE. 10 (8), e0135688 (2015).

- Pilling, E. D., Bromleychallenor, K. A. C., Walker, C. H., Jepson, P. C. Mechanism of synergism between the pyrethroid insecticide lambda-cyhalothrin and the imidazole fungicide prochloraz, in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L). Pestic Biochem Phys. 51 (1), 1-11 (1995).

- Johnson, R. M., Wen, Z., Schuler, M. A., Berenbaum, M. R. Mediation of pyrethroid insecticide toxicity to honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. J. Econ. Entomol. 99 (4), 1046-1050 (2006).

- Steffan, S. A., Dharampal, P. S., Diaz-Garcia, L. A., Currie, C. R., Zalapa, J. E., Hittinger, C. T. Empirical, metagenomic, and computational techniques illuminate the mechanisms by which fungicides compromise bee health. JoVE. (128), e54631 (2017).

- Batra, S. W. T. Solitary bees. Sci Am. 250 (2), 120-127 (1984).

- Linsley, E. G. The ecology of solitary bees. Hilgardia. 27 (19), 543-599 (1958).

- Garibaldi, L. A., et al. Wild Pollinators Enhance Fruit Set of Crops Regardless of Honey Bee Abundance. Science. 339 (6127), 1608-1611 (2013).

- Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. . How to manage the blue orchard bee. , (2001).

- Keller, A., Grimmer, G., Steffan-Dewenter, I. Diverse microbiota identified in whole intact nest chambers of the red mason bee Osmia bicornis (Linnaeus 1758). PLoS ONE. 8 (10), e78296 (2013).

- Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. Development and Emergence of the Orchard Pollinator Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Environmental Entomology. 29 (1), 8-13 (2000).

- Brittain, C., Potts, S. G. The potential impacts of insecticides on the life-history traits of bees and the consequences for pollination. Basic and Applied Ecology. 12 (4), 321-331 (2011).

- Arena, M., Sgolastra, F. A meta-analysis comparing the sensitivity of bees to pesticides. Ecotoxicology. 23 (3), 324-334 (2014).

- Ladurner, E., Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P., Maini, S. Foraging and nesting behavior of Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in the presence of fungicides: cage studies. J Econ Entomol. 101 (3), 647-653 (2008).

- Huntzinger, A. C. I., James, R. R., Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. Fungicide tests on adult alfalfa leafcutting bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Econ Entomol. 101 (4), 1088-1094 (2008).

- Tsvetkov, N., et al. Chronic exposure to neonicotinoids reduces honey bee health near corn crops. Science. 356 (6345), 1395-1397 (2017).

- Mao, W., Schuler, M. A., Berenbaum, M. R. Disruption of quercetin metabolism by fungicide affects energy production in honey bees (Apis mellifera). P Natl Acad Sci. 114 (10), 2538-2543 (2017).

- Blacquière, T., Smagghe, G., Van Gestel, C. A. M., Mommaerts, V. Neonicotinoids in bees: A review on concentrations, side-effects and risk assessment. Ecotoxicology. 21 (4), 973-992 (2012).

- Sgolastra, F., Tosi, S., Medrzycki, P., Porrini, C., Burgio, G. Toxicity of spirotetramat on solitary bee larvae, Osmia cornuta (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), in laboratory conditions. Journal of Apicultural Science. 59 (2), 73-83 (2015).

- Mader, E., Spivak, M., Evans, E. . Managing Alternative Pollinators. , (2010).

- Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. Developing and establishing bee species as crop pollinators: the example of Osmia spp.(Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) and fruit trees. B Entomol Res. 92 (1), 3-16 (2002).

- Sampson, B. J., Rinehart, T. A., Kirker, G. T., Stringer, S. J., Werle, C. T. Phenotypic variation in fitness traits of a managed solitary bee, Osmia ribifloris (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Econ Entomol. 108 (6), 2589-2598 (2015).

- Sampson, B. J., Cane, J. H., Kirker, G. T., Stringer, S. J., Spiers, J. M. Biology and management potential for three orchard bee species (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae): Osmia ribifloris Cockerell, O. lignaria (Say) and O.chalybea Smith with emphasis on the former. Acta Hort. 810, 549-555 (2009).

- Hladik, M. L., Vandever, M., Smalling, K. L. Exposure of native bees foraging in an agricultural landscape to current-use pesticides. Sci Total Environ. 542, 469-477 (2016).

- Long, E. Y., Krupke, C. H. Non-cultivated plants present a season-long route of pesticide exposure for honey bees. Nat Commun. 7, (2016).

- Krupke, C. H., Hunt, G. J., Eitzer, B. D., Andino, G., Given, K. Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS ONE. 7 (1), e29268 (2012).

- Stoner, K. A., Eitzer, B. D. Using a hazard quotient to evaluate pesticide residues detected in pollen trapped from honey bees (Apis mellifera) in Connecticut. PLoS ONE. 8 (10), e77550 (2013).

- Sánchez-Bayo, F., Goulson, D., Pennacchio, F., Nazzi, F., Goka, K., Desneux, N. Are bee diseases linked to pesticides? – A brief review. Environ Int. 89, 7-11 (2016).

- Steffan-Dewenter, I., Klein, A. -. M., Gaebele, V., Alfert, T., Tscharntke, T. Bee diversity and plant-pollinator interactions in fragmented landscapes. Specialization and generalization in plant-pollinator interactions. , 387-410 (2006).

- Kremen, C., Ricketts, T. Global perspectives on pollination disruptions. Conserv Biol. 14 (5), 1226-1228 (2000).

- Memmott, J., Waser, N. M., Price, M. V. Tolerance of pollination networks to species extinctions. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 271 (1557), 2605-2611 (2004).

- Spear, D. M., Silverman, S., Forrest, J. R. K. Asteraceae pollen provisions protect Osmia mason bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) from brood parasitism. The American Naturalist. 187 (6), 797-803 (2016).

- Rust, R. W. Biology of Osmia (Osmia) ribifloris Cockerell (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Kansas Entomol Soc. 59, 89-94 (1986).

- Torchio, P. F. Osmia ribifloris, a native bee species developed as a commercially managed pollinator of highbush blueberry (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Kansas Entomol Soc. 63 (633), 427-436 (1990).

- Sanchez-Bayo, F., Goka, K. Pesticide residues and bees – A risk assessment. PLoS ONE. 9 (4), e94482 (2014).

- Kasiotis, K. M., Anagnostopoulos, C., Anastasiadou, P., Machera, K. Pesticide residues in honeybees, honey and bee pollen by LC-MS/MS screening: Reported death incidents in honeybees. Sci Total Environ. 485 (1), 633-642 (2014).

- Stanley, J., Sah, K., Jain, S. K., Bhatt, J. C., Sushil, S. N. Evaluation of pesticide toxicity at their field recommended doses to honeybees, Apis cerana and A. mellifera through laboratory, semi-field and field studies. Chemosphere. 119, 668-674 (2015).

- Praz, C. J., Müller, A., Dorn, S. Specialized bees fail to develop on non-host pollen: Do plants chemically protect their pollen?. Ecology. 89 (3), 795-804 (2008).

- Sedivy, C., Müller, A., Dorn, S. Closely related pollen generalist bees differ in their ability to develop on the same pollen diet: Evidence for physiological adaptations to digest pollen. Funct Ecol. 25 (3), 718-725 (2011).

- Williams, N. M. Use of novel pollen species by specialist and generalist solitary bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Oecologia. 134, (2003).

- Graystock, P., Rehan, S. M., McFrederick, Q. S. Hunting for healthy microbiomes: determining the core microbiomes of Ceratina, Megalopta, and Apis bees and how they associate with microbes in bee collected pollen. Conserv Genet. 18 (3), 1-11 (2017).

- Bosch, J., Vicens, N. Relationship between body size, provisioning rate, longevity and reproductive success in females of the solitary bee Osmia cornuta. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 60 (1), 26-33 (2006).

- Bosch, J., Vicens, N. Body size as an estimator of production costs in a solitary bee. Ecol Entomol. 27 (2), 129-137 (2002).

- Radmacher, S., Strohm, E. Factors affecting offspring body size in the solitary bee Osmia bicornis (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae). Apidologie. 41 (2), 169-177 (2010).

- Seidelmann, K. Open-cell parasitism shapes maternal investment patterns in the Red Mason bee Osmia rufa. Behav Ecol. 17 (5), (2006).

- Becker, M. C., Keller, A. Laboratory rearing of solitary bees and wasps. Insect Science. 23 (6), 918-923 (2016).

- Bosch, J. The nesting behaviour of the mason bee Osmia cornuta (Latr) with special reference to its pollinating potential (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae). Apidologie. 25, 84-93 (1994).

- Krunić, M., Stanisavljević, L., Pinzauti, M., Felicioli, A. The accompanying fauna of Osmia cornuta and Osmia rufa and effective measures of protection. B Insectol. 58 (2), 141-152 (2005).

- Elliott, S. E., Irwin, R. E., Adler, L. S., Williams, N. M. The nectar alkaloid, gelsemine, does not affect offspring performance of a native solitary bee, Osmia lignaria (Megachilidae). Ecol Entomol. 33 (2), 298-304 (2008).

- Hendriksma, H. P., Härtel, S., Steffan-Dewenter, I. Honey bee risk assessment: New approaches for in vitro larvae rearing and data analyses. Methods Ecol and Evol. 2 (5), 509-517 (2011).

- Aupinel, P., et al. Improvement of artificial feeding in a standard in vitro method for rearing Apis mellifera larvae. B Insectol. 58 (2), 107-111 (2005).

- Beekman, M., Ratnieks, F. L. W. Long-range foraging by the honey-bee, Apis mellifera L. Funct Ecol. 14 (4), 490-496 (2000).

- Gathmann, A., Tscharntke, T. Foraging ranges of solitary bees. J Anim Ecol. 71 (5), 757-764 (2002).

- Greenleaf, S. S., Williams, N. M., Winfree, R., Kremen, C. Bee foraging ranges and their relationship to body size. Oecologia. 153 (3), 589-596 (2007).

- . Bee Pollen Supplement – Bee Rescued Available from: https://beerescued.com/product/bee-rescued-bee-pollen-supplement/ (2018)

- Cane, J. H., Griswold, T., Parker, F. D. Substrates and Materials Used for Nesting by North American Osmia Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes: Megachilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 100 (3), 350-358 (2007).