Las leyes del movimiento de Newton

English

COMPARTILHAR

Visão Geral

Fuente: Andrew Duffy, PhD, Departamento de física de la Universidad de Boston, Boston, MA

Este experimento analiza en diversas situaciones que implican dos objetos interactúan.

En primer lugar, el experimento examina las fuerzas que dos objetos se aplican unos a otros mientras que chocan. Los objetos son las carretillas que tienen masas variable. El propósito de este experimento es descubrir cuando la fuerza que ejerce el primer carro por el otro es la misma magnitud que la fuerza que ejerce el carro de segunda en la primera, como cuando estas dos fuerzas tienen magnitudes diferentes.

En segundo lugar, examina las fuerzas que ejercen dos objetos el uno del otro cuando un carro es empujar o tirar el otro. Una vez más, el enfoque es en la exploración de las situaciones en que las dos fuerzas tienen la misma magnitud y que tienen magnitudes diferentes.

Princípios

El objetivo principal de este experimento es explorar la tercera ley de Newton.

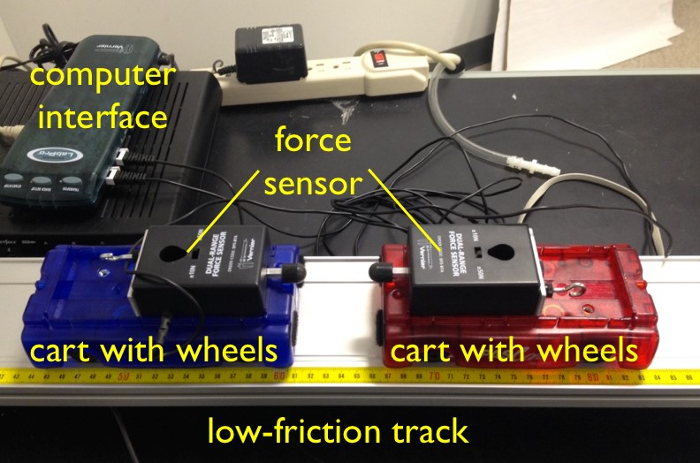

El aparato consiste en dos carros, cada uno con un sensor de fuerza montado en la parte superior (figura 1). Los sensores están conectados a una computadora mediante una interfaz de computadora dedicada. Cada sensor de fuerza mide la fuerza ejercida sobre ella por el otro sensor de fuerza durante la colisión o la situación de vaivén.

Figura 1. La configuración básica. Los componentes clave del aparato son los dos carros con ruedas, cada una con un sensor de fuerza montado en la parte superior y una interfaz de computadora.

Procedimento

Resultados

Newton's third law states that whenever two objects interact, the second object exerts a force on the first object that is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the force the first object exerts on the second. This is simple to state, but it can be hard to accept. For example, it is often assumed that the force a larger object exerts on a smaller object is larger than the force the smaller object exerts back on the larger object.

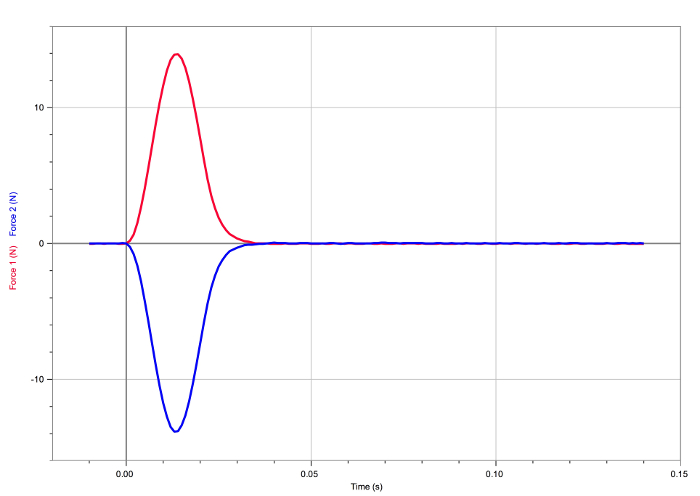

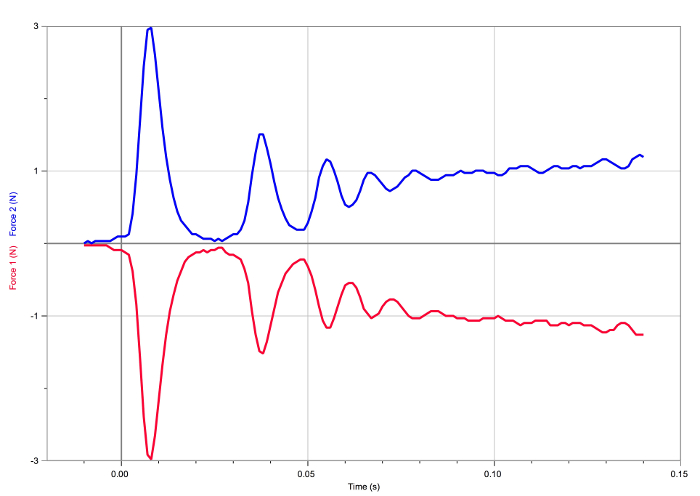

Figure 2. Result of the first collision. The forces experienced by the carts are equal and opposite.

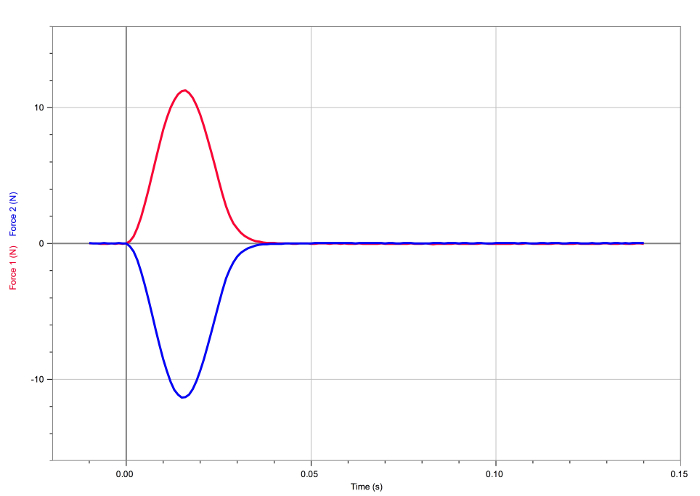

Figure 3. Result of the second collision. The forces experienced by the carts are equal and opposite.

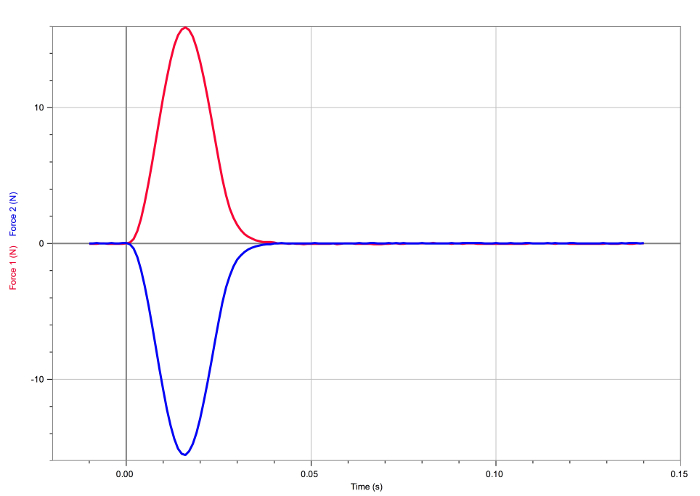

Figure 4. Result of the third collision. The forces experienced by the carts are equal and opposite.

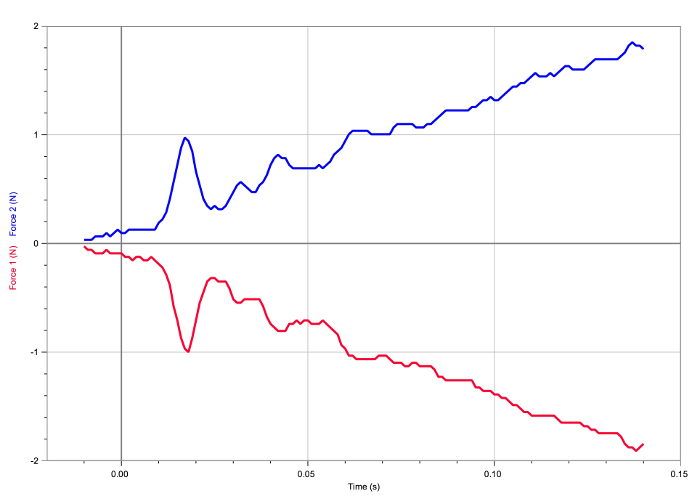

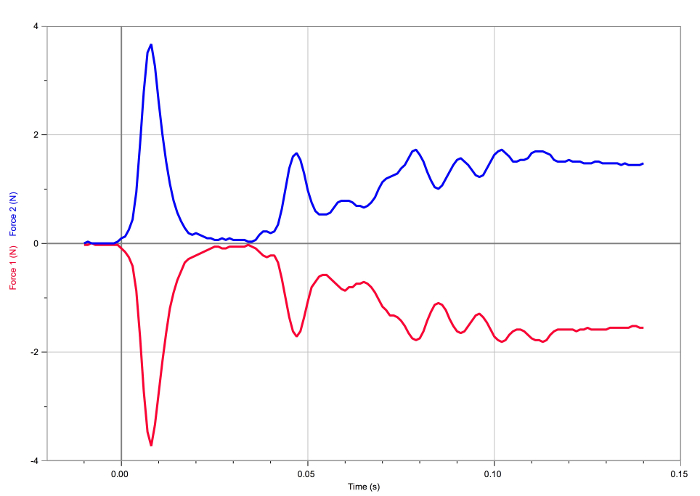

Figure 5. Result of the first pushing/pulling situation. The forces experienced by the carts are equal and opposite.

Figure 6. Result of the second pushing/pulling situation. The forces experienced by the carts are equal and opposite.

Figure 7. Result of the third pushing /pulling situation. The forces experienced by the carts are equal and opposite.

Applications and Summary

The concept addressed in this experiment, namely that, in all interactions, the force one object applies to another is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the force applied by the second object back on the first, has many applications. For example, (1) the gravitational force the Sun applies to the Earth is equal and opposite to the gravitational force the Earth applies to the Sun. (2) The gravitational force the Earth applies to the Moon is equal and opposite to the gravitational force the Moon applies to the Earth. (3) The gravitational force the Earth exerts on an apple is equal and opposite to the gravitational force the apple applies to the Earth. (4) In a collision, such as that between a car and a truck on the street or that between two football players, the forces are always equal and opposite, no matter how the masses compare. (5) When a person stands on a floor or sits on a chair, the force exerted on that person by the floor or the chair is equal and opposite to the force the person exerts on the floor or chair.

Transcrição

Newton’s laws of motion are the basis for classical mechanics and describe the relationship between an object and the forces acting upon it.

For example, when a rocket is at rest on the launchpad before launch, the rocket and the ground exert equal-and-opposite forces on one another. To take off, or when the rocket is in space, the expanding gas from the burning fuel pushes against the rocket and propels it forward. Less apparent, however, is that the rocket pushes against the gas at the same time. These simple phenomena obey Newton’s laws of motion, though the forces at work may not be obvious because forces are not always visible.

This video will introduce the basics of Newton’s laws of motion, and then demonstrate the concept through a series of experiments measuring the forces between two wheeled carts in various situations.

Newton’s laws of motion consist of three key laws. The first law is the most simple, and states that an object at rest stays at rest, unless acted upon by a force. Similarly, an object in motion stays in motion unless acted upon by a force. Specifically, if the net forces on the object are zero, the velocity of the object is constant, whether the velocity is zero or not. However, an applied force, such as kicking the ball or hitting the wall, causes the velocity of the object to change.

Newton’s second law states that the rate of change of an objects velocity, called acceleration, is directly proportional to the force applied to it. The proportionality factor is the mass of the object itself.

In other words, if an object is accelerating, there is a net force on it. This law is consistent with the first law, where the rate of change of an object’s velocity-its acceleration- is zero when there is no net force applied.

Finally, Newton’s third law states that the forces of two objects acting upon each other are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction

This behavior is often hard to understand. For example, when two objects of different masses collide, it is often assumed that the more massive object exerts a larger force than the less massive object. However, the forces are equal and opposite.

Newton’s third law is commonly expressed with the phrase, “for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” To be specific, the forces between two interacting objects are called “action-reaction pairs,” which are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

But the responses of the objects-that is, their accelerations-may not be equal. This is because acceleration is inversely proportional to mass according to Newton’s second law.

Consider what happens when a very large truck collides with a very small car. If action and reaction refer to the impact forces between them, then indeed the action does produce an equal and opposite reaction. But because of the significant differences in masses between truck and car, the effects of these forces are very different. The car rebounds catastrophically while the much more massive truck hardly changes course.

Now that the principles of Newton’s laws of motion have been presented, let’s take a look at the behavior of moving objects, and relate their behavior to Newton’s third law of motion.

The following experiments use two wheeled carts, which slide on a long, low friction track.

Each cart is equipped with a force sensor connected to a computer interface for recording data. Each sensor is positioned to strike the sensor of the other cart during a collision, or to push or pull on the sensor of the other cart as they slide on the track.

Before starting the collision experiments, the force sensors must be set up for impact and configured for the expected level of force. First, screw a rubber bumper onto the plunger of each force sensor. Locate the slide switch on top of the force sensor. Set this switch to the 50 Newton position for each sensor.

The “Collect” button, which looks like a green arrow, starts data collection. Before each experiment, press the button next to this green arrow to zero the force sensor.

Zero both force sensors then check them to make sure the positive direction for each is defined to the right. Push in the sensor with the plunger that points right. The force reading should be positive.

Push in the sensor with the plunger that points left. The force reading should be negative. If both force readings are wrong, then reverse the positions of the carts.

If only one reading is wrong, then go to the “Experiment” menu, and select “Setup Sensors.” Choose the appropriate force sensor and select “Reverse Direction.”

After the force sensors have been configured correctly, the apparatus is ready for the first experiment, which uses carts of equal mass. Choose one cart to be stationary at the start of the test.

Zero both force sensors then press the “Collect” button to start data recording. Push and release the other cart so it slides on its own and collides with the stationary cart.

After impact, the computer displays a plot of the “force vs. time” recorded by each sensor. Magnitudes of peak force should be between 8 and 20 Newtons. If the peak force is outside this range, then repeat the experiment and adjust how hard the cart is pushed.

When carts with equal mass collide, this plot shows that the forces they experience are equal and opposite. Because acceleration equals force divided by mass, each cart accelerates with the same magnitude, but in opposite directions.

The second collision experiment repeats the first experiment but with carts of unequal mass. Choose one cart to be stationary and load it with one or more weights so it has 2 to 3 times the mass of the moving cart.

Zero both force sensors, press the “Collect” button and repeat the collision experiment by pushing the cart without weights into the weighted cart

When the less massive moving cart collides with the more massive, stationary one, they rebound with very different speeds. Despite appearances, the magnitudes of the forces are actually equal, as the plots clearly show. This behavior may be confusing but it is because the less massive cart experiences greater acceleration than the more massive one, again because acceleration equals force divided by mass.

Next, transfer the weights from the stationary cart to the moving cart to reverse the roles of the carts. Repeat the experiment with the moving cart being more massive and the stationary cart being less massive. Zero both force sensors, and press the “Collect” button. Repeat the experiment by pushing the weighted cart into the un-weighted one.

As with the previous experiment, the two carts rebound with very different speeds, because of their different masses. However, the impact forces still have equal magnitudes. So, regardless of whether the carts have equal or different masses, the collision forces are always equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

Newton’s third law of motion applies not only to collisions, but also to all situations where two objects interact.

Newton’s third law also applies to the pushing and pulling interactions between two objects. To examine this phenomenon, the cart experiment was modified by replacing the rubber bumpers on the force sensors with hooks, and then hooking the carts together. The triggering condition was also reversed in the data collection software.

When carts of equal mass pushed and pulled the other, the forces were equal and opposite, despite the changing direction of motion. When two carts of unequal mass were pushed and pulled the phenomenon still holds true.

Physicists trying to understand planet formation often study collisions. In this example, dust particles were prepared to simulate collisions in the early solar system. The particles were dropped, and their collision recorded.

The colliding particles exerted forces against each other, which were equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. When both objects remained intact, the impact forces caused them to rebound.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s introduction to Newton’s laws of motion. You should now understand the basics of the three laws, how they describe motion and forces on objects. Thanks for watching!