说服: 激励因素影响态度变化

English

COMPARTILHAR

Visão Geral

资料来源: 威廉 · 布雷迪 & 杰范韦尔 — — 纽约大学

几十年的社会心理研究试图了解一个根本的问题,贯穿于我们社会的生活,包括政治、 市场营销和公共卫生;即,如何被人说服改变主意、 人或对象的态度?传统的工作发现有影响说服是否成功的关键因素或不包括的有说服力的消息 (源),源参数消息和内容 (”内容”)。例如,专家来源和合理的论据的消息则通常更有说服力。然而,随着更多的研究,进行相互矛盾的研究结果开始领域内出现了: 一些研究发现专家来源和很好的论据并不总是需要成功劝说。在 20 世纪 80 年代,心理学家理查德 • 佩,约翰 Cacioppo 和他们的同事提出了一个模型说服占研究中混杂的结果。1,2他们提议拟订似然模型的劝说下,其中指出,说服发生通过两个途径: 中央或者周边的运输路线。有说服力的消息处理时通过中央路线,人们从事有关的消息,仔细的思考和因此,内容 (即,论战的质量) 事项为成功说服。然而,当通过周边路线处理邮件,源 (例如,一个专家的来源) 是更重要的是成功说服。

如果人们动机要注意邮件主题,他们倾向于处理通过中央的路线,消息和消息内容具有更重要的意义。另一方面,当人们没有动机要注意邮件主题,邮件是更有可能通过外周途径处理和因此消息的来源是更重要。小资、 Cacioppo,和高盛的启发,该视频演示了如何设计一个任务来测试不同的路线,使用消息成功说服了。1

Princípios

Procedimento

Resultados

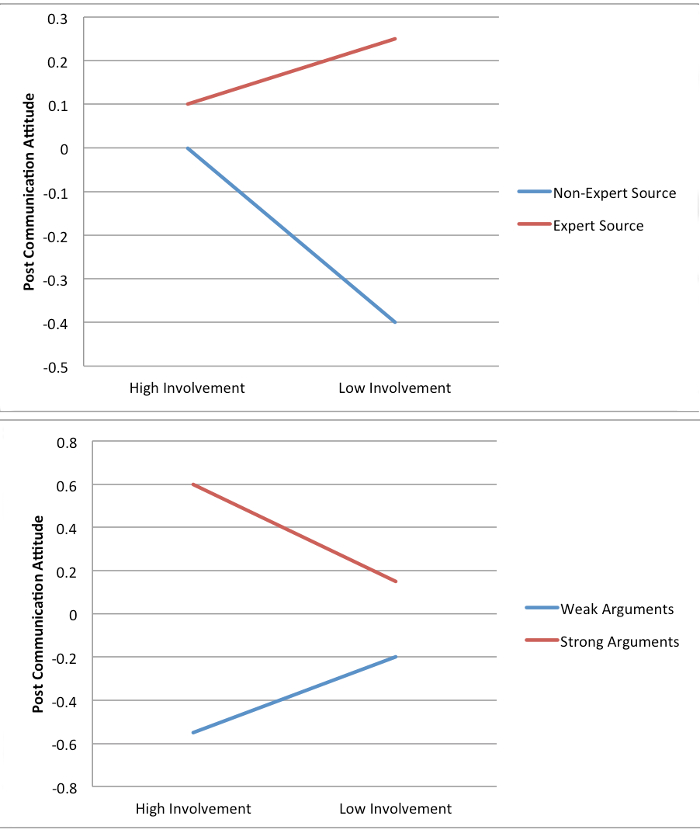

The results showed a main effect of argument quality: The strong arguments lead to greater agreement with the message than weak arguments. There was also a main effect of source: Averaged across the other conditions there was greater agreement for the message when the source had high expertise than when the source had low expertise. However, of particular interest was the discovery of an interaction effect (Figure 1). When participants were in the high-relevance group, the effect of argument quality was stronger than when the participants were in the low relevance group. The opposite was true for the source condition: when participants were in the low-relevance group, the effect of high-source expertise was greater than when the participants were in the high-relevance group.

Figure 1: The interactive effect of source expertise and motivational relevance (top) or argument quality and motivational relevance (bottom) on agreement toward the comprehensive exam message. Participants agreed with the message more if the source was an expert only when the motivational relevance was low. However, participants agreed with the message more if the argument quality was strong only when the motivational relevance was high.

Applications and Summary

In the debate over what factors lead to a message being persuasive, this experiment provides a careful test of the idea that motivational factors, such as personal relevance of the message, play a pivotal role in determining the impact of factors that generally affect persuasion, including source characteristics and argument quality. The result of this experiment and the Elaboration Likelihood Model that took hold because of its results, steered the field in a new direction when it was in a battle over whether source characteristics or argument quality were the most important factors influencing persuasion. These data suggest that the answer is they are both important, but the motivational context in which the message is embedded is important to consider to determine when the factors will exert their influence on persuasion.

These results have considerable implications for areas such as marketing, politics, and public health. In terms of marketing, businesses can use the findings of the study to help design effective campaigns that are designed to spread positive messages about their product. For example, if an ad campaign on some media outlet is targeted at an audience for which the product is personally relevant (e.g., a video game targeting a demographic of teenage boys), then the research suggests that the advertisement should include factual evidence the game is a good one to buy (e.g., statistics demonstrating that everyone is playing it). If the advertisement is being presented to another audience that may buy the game but is not personally relevant for them (e.g., parents looking to a buy a game for the kid), then the source of the advertisement message is more important (e.g., the advertisement is endorsed by a pro-gamer or a computer technician).

In terms of politics, political candidates can try to persuade people about their policies differentially based on what crowd they are speaking to. When the policies they are discussing are directly relevant to their crowd, such as the case of discussing one’s position on abortion to a crowd of young women, the politicians should use high quality arguments rather than rely on personal anecdotes. In other cases where the crowd is less interested in the policy being discussed, as in the case of discussing retirement policies to a young college crowd, tactics that make the candidate appear to be the expert on the issue may be more important than crafting a quality argument.

Finally, in terms of public health and other related fields, the findings of this study can be used to create effective campaigns that attempt to get the public to behave different than their currently behavior. For example, if campaigns about hypertension are targeted in low-income African American communities where hypertension rates higher than average, constructing an argument that appears to be supported by data and facts may be more important than emphasizing the source of the public-service advertisement.

Referências

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1984). Source Factors and the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 668-672.

- Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 847-855.

Transcrição

How someone can be persuaded to change their attitude towards another person, idea, or object depends on a number of key factors, including the source and content of the message.

For instance, expert sources with sound arguments are typically more persuasive—people are more likely to buy into the message. In particular, such information aids persuasion when individuals are motivated to pay close attention and process the details at a higher level of thinking, known as high elaboration.

However, sometimes people are not motivated to carefully think about issues at hand, especially if the details are not personally relevant. In this case, they don’t process communication in the same way—their mental effort is low. With such minimal elaboration, cognitive misers can rely more on general impressions than well-crafted arguments for persuasion.

These examples illustrate different ways of processing stimuli—centrally and peripherally—and their outcomes on attitude change, which forms the basis of the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion.

This video demonstrates the original experimental methods developed by Richard Petty, John Cacioppo, and colleagues to investigate the success of persuasive messages under different motivational circumstances.

In this experiment, participants think they are assessing the audio quality of recorded arguments, when in reality that’s a cover task, as they are being manipulated with recordings that vary in their amounts of motivational relevance, argument content, and source expertise.

For the first factor—motivational relevance—participants are either told that a policy change will affect them soon, which constitutes high involvement, or that it won’t be instituted for some time—of low importance.

To manipulate the second factor, argument strength, participants are further divided into hearing a strong message—one that incorporates data and statistics—or a weak one, content that is based on personal opinions and anecdotal evidence.

Finally, for the third variable—level of expertise—participants are told that the message was generated by highly endowed university professionals—expert sources—or prepared by a local high school student—non-experts.

After listening to the recorded statements, participants are asked to rate the extent of their agreement with the policy implementations on a scale from 1, do not agree, to 11—agree completely. The responses are then standardized and form the dependent variable—post-communication attitude scores.

Given the number of factors involved, it is hypothesized that participants hearing strong arguments from expert sources will show greater agreement with the messages than those listening to weak arguments from non-experts.

However, given the potential interaction with motivational relevance, it might be the case that persuasion is influenced differentially, dependent on the level of involvement. Thus, for messages to be convincing, their motivational context should be considered an influential force on persuasion.

Before starting the experiment, conduct a power analysis to determine the appropriate number of participants required for this 2 x 2 x 2 factorial design. To begin, greet each one in the lab and explain the cover story: that they will be assessing the quality of audio recordings on a proposed academic policy change.

First, split participants based on the relevance factor: For those randomly assigned to high-relevance say: “The policy change you are about to hear about will be implemented next year.” and to the low-relevance group: “The policy change you are about to hear about will be instituted in 10 years.”

Then, to assess the influence of argument strength, further divide the participants into those who will hear either a strong case based on facts or a weak one centered on anecdotes.

For the final factor of source expertise, notify some participants that the recording was generated by an expert at a prestigious university and the rest that it was composed by non-expert local high school students.

Now instruct them to put on the headphones and start the audio recordings: “In the new policy, seniors are required to take a comprehensive exam to graduate. The policy led to greater standardized achievement scores when implemented at other universities.” and “In the new policy, seniors are required to take a comprehensive exam to graduate. A friend of the authors took the exam enforced by the policy and now has a prestigious academic position.”

When the recordings are over, return with questionnaires. Have each participant rate the extent of their agreement with the policy change on an 11-point scale from strongly opposed to strongly in favor.

To maintain the cover story of assessing the quality of recordings, also ask participants to rate the speaker’s voice quality, the quality of delivery, and the level of enthusiasm.

Finally, debrief participants and thank them for taking part in the study.

To visualize the data, plot the average agreement measure—post-communication attitudes—first comparing argument strength against the levels of motivational relevance.

Based on an overall 2 x 2 x 2 ANOVA, there was a main effect of strength, where strong statements led to greater agreement than weak ones. Furthermore, there was an interaction effect: When participants were in the high-relevance group, the effect of argument quality was stronger than for those who were in the low-relevance group.

In addition, graph the average values for those exposed to different levels of expertise and motivational relevance. In this case, there was a main effect of source, with greater agreement when the level of expertise was high versus low.

Here, the interaction effect was opposite: For participants in the low-relevance group, the effect of high-source expertise was greater than for those in the high-relevance condition. Together, these results demonstrate different routes to successful persuasion.

Now that you are familiar with the factors leading to persuasion, let’s look at how researchers apply the model to influence marketing products and even public health campaigns.

Businesses can use the Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion to maximize their marketing to target audiences. For example, if trying to sell a video game, ads directed towards highly relevant teenage boys should include a strong statement with statistics that everyone is playing it.

Whereas, flyers trying to convince parents that don’t play—considered low-relevance—to buy it for their child should have credible and expert sources like a pro-gamer endorse the product.

Politicians can also use the model to enhance the persuasiveness of their speeches. When policies are directly relevant to their crowd, such as discussing childcare rights with a crowd of expecting mothers, politicians should use high-quality arguments rather than anecdotes.

In contrast, if the crowd is less interested, like in a discussion of retirement policies to a group of young students, the politician should appear to be an expert instead of crafting a quality argument.

Lastly, the findings can also be used to change people’s attitudes about health care. For example, if a campaign on hypertension is targeting highly relevant, low-income African American communities where rates are high, an argument that is supported by data and facts is more important than emphasizing the source of the public-service announcement.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on the success of persuasive messages under varied circumstances. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design and execute an experiment with manipulations of motivation, strength of argument, and expertise of source, how to analyze and assess the results, as well as how to apply the principles to a number of real-world situations.

Thanks for watching!