נידוי: ההשפעות של התעלמות דרך האינטרנט

English

COMPARTILHAR

Visão Geral

מקור: פיטר מנדה-סיידלקי וג’יי ואן באבל – אוניברסיטת ניו יורק

נידוי חברתי מוגדר כהתעלמות ומודר בנוכחות אחרים. חוויה זו הינה תופעה חברתית נרחבת וחזקה, הנצפת הן בבעלי חיים והן בבני אדם, בכל שלבי ההתפתחות האנושית, ובכל מיני מערכות יחסים, תרבויות וקבוצות ומוסדות דיאדיים. יש הטוענים כי נידוי משרת פונקציה רגולטורית חברתית, אשר יכול לשפר את הלכידות הקבוצתית ואת הכושר על ידי הסרת אלמנטים לא רצויים. 1 ככזה, תחושת הנידוי יכולה לשמש אזהרה לשנות את התנהגותו של האדם, על מנת להצטרף מחדש לקבוצה. 2

המחקר בפסיכולוגיה חברתית התמקד בהרחבה בהשלכות הרגשיות וההתנהגותיות של נידוי חברתי. לדוגמה, אנשים שהיו מנודים מדווחים על תחושת דיכאון, בודדה, חרדה, מתוסכלת וחסרת אונים, 3 ובעוד שהם עשויים כעתלהעריך את מקור הנידוי שלהם בצורה שלילית יותר, הם גם ינסו לעתים קרובות להתחנף אליהם. 2 יתר על כן, יש לשער כי הפחד של נידוי מונע בסופו של דבר על ידי צורך חזק להשתייך ולהרגיש כלול, ומשמש לחץ חברתי המוביל לקונפורמיות, ציות וניהול רושם. 4

במודל שפיתח ויליאמס (1997), נידוי מכוון באופן ייחודי לארבעה צרכי ליבה – שייכות, הערכה עצמית, שליטה וקיום משמעותי – מה שמעורר מצב רוח שלילי, חרדה, עוררות פיזיולוגית ותחושות פגועות. 5 בתמורה, כדי להגן מפני אי נוחות פסיכולוגית כזו, אנשים מנודים עשויים לנסות להתמודד על ידי חיזוק צרכי הליבה האלה. לדוגמה, הם עשויים לנסות להתאים באופן ניכר לנורמות קבוצתיות כדי לשקם את מקומם בקרב הקולקטיב.

Princípios

Procedimento

Resultados

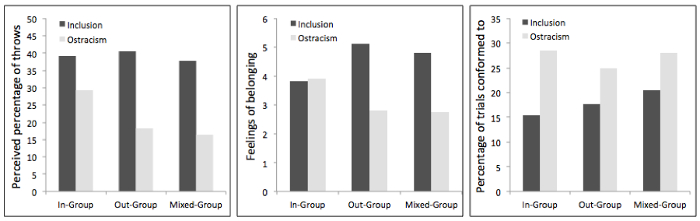

In the original Williams, Cheung, and Choi investigation in 2000, the authors observed strong main effects of ostracism across three key dependent variables. Participants who were ostracized reported receiving fewer throws, reported feeling lower feelings of belonging, and conformed on a higher percentage of trials, compared to participants who were included (Figure 1).

While the effects of group membership were somewhat more mixed, the authors reported two interactions between ostracism and group membership, one concerning the manipulation check and one concerning feelings of belonging. Specifically, individuals in the in-group condition did not show significant differences between perceived throws received between the ostracism and inclusion groups, nor they differ in terms of feelings of belonging. Nevertheless, participants who were ostracized in in-group groups still conformed significantly more than individuals who were included.

Figure 1: Means for three dependent variables (perceived percentage of throws, feelings of belonging, and percentage of trials conformed to) as a function of the type of interaction (inclusion or ostracism) and group memberships (in-group, out-group, and mixed-group). The figure on the left shows that targets of ostracism correctly perceived that they received less throws. Moreover, the figures in the middle and right show that targets of ostracism reported lower feelings of belonging and were more likely to conform to the unanimous incorrect judgments of a new group.

Applications and Summary

Based on these results, Williams and colleagues concluded that they had successfully developed a tool for robustly inducing feelings of social ostracism in participants, even without direct face-to-face interaction. Indeed, in their investigation, being excluded over the internet led participants to feel less belonging, and in turn, led participants to conform to the beliefs of a new group of individuals. The authors interpreted this behavior as an attempt to reaffirm feelings of belonging. These results are striking given the relative simplicity of the context of ostracism. Players do not communicate, they cannot see each other, and they have no reason to believe that they will ever interact again. Yet momentary exclusion produces robust affective and behavioral consequences.

Ostracism is a powerful and salient social signal. When we are ostracized, we feel upset, excluded, and unsure of our place in the social hierarchy. As such, we may take steps to restore that place—either by attempting to get back into the good graces of the ostracizer, or by finding new acceptance elsewhere. The Cyberball task represents a robust and efficient means of inducing these feelings experimentally, either through a laboratory set-up, or conducted remotely over the internet.

As the task itself is relatively decontextualized, any number of modifications might be made to any aspect of it (e.g., the instructions, the players, the nature of the ball-tossing interaction) to test various hypotheses. The induction might be used to test various responses to ostracism, both anti-social (e.g., aggression) and pro-social (e.g., ingratiation). The task might be used (and indeed has by some authors) to examine the physiological components8 and neural bases supporting social ostracism.9 Finally, the original authors have suggested that while in its original inception, Cyberball is used to manipulate feelings of ostracism, it might also be used as a dependent measure (e.g., of prejudice or altruism), by focusing on participants’ choices to include or exclude the other players.

Referências

- Gruter, M., & Masters, R. D. (1986). Ostracism as a social and biological phenomenon: An introduction. Ethology and Sociobiology, 7, 149-158.

- Williams, K. D., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 693-706.

- Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 79, 748-762.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

- Williams, K. D. (1997). Social ostracism. In R. Kowalski (Ed.), Aversive interpersonal behaviors (pp. 133-170). New York: Plenum.

- Williams, K. D., & Jarvis, B. (2006). Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior research methods, 38, 174-180.

- Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 560-567.

- Kelly, M., McDonald, S., & Rushby, J. (2012). All alone with sweaty palms—Physiological arousal and ostracism. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 83, 309-314.

- Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290-292.

Transcrição

Most people want to be socially connected and included with others. Researchers can examine what happens when the opposite occurs—being ignored and excluded—which is known as ostracism.

With the rise of social media, the experience of ostracism has become ubiquitous. For example, during a browsing session, an individual may see pictures from a party that they apparently weren’t invited to attend.

On account of her perceived absence, she unleashes a whirlwind of emotions, including sadness, anxiety, arousal, and hurt feelings. As irrational as it seems, the internet-based observation—not even in-person—was enough to thwart core desires of belonging, self-esteem, and meaningful existence.

This video demonstrates how to establish group connections, induce ostracism in a laboratory setting using a computerized game Cyberball, and measure the subsequent effects on conformity and feelings of belonging based on the original experiment from Williams, Cheung, and Choi.

This experiment consists of three parts: establishing group membership ties, inducing ostracism, and examining the effects on conformity and belonging.

In Phase 1, group membership, all participants are given an initial questionnaire, which probes the computer platform they use. In addition, they are asked to write brief descriptions of what they think both groups of users are like. This latter portion serves as a manipulation check to see if participants make more positive comments about others who use same computer as they do.

To manipulate the strength of group ties, participants are then are given different interaction assignments. They are put into an in-group—where all players use the same type, an out-group—the others prefer the opposite, or a mixed group.

During Phase 2, critical for inducing ostracism, participants play a computerized game called Cyberball, where there are three animated characters tossing and catching a ball. When it’s tossed to the participant—represented as the middle player—they are instructed to click on the intended recipient of their choice.

Within the first three throws of the game, the participant always starts off with possession of the ball. Subsequently, every player is given the chance to throw and catch the ball once.

On the fourth throw, the participant will once again be in possession of the ball and choose who to throw it to. From the fifth throw and onwards, participants are randomly assigned by a predetermined algorithm to either be included or ostracized.

Participants in the inclusion conditions will continue to receive the ball for a third of the throws, whereas those in the ostracism conditions will not be thrown the ball again.

In Phase 3—what participants are told is the real primary task involving perceptual comparisons—another computerized task is carried out. Here, they think that they are choosing their line-up number within a new six-person group, when in reality, the spinning wheel is rigged to stop at the sixth position.

For each trial, a simple geometric figure—like a triangle—appears on the screen, then disappears, and reappears embedded within one of six complex figures. Participants are asked to identify the correct figure—that is, the complex one containing the initial simple shape.

Since all participants in the study respond last, they will see how the “others” reply across six trials. During the 1st, 2nd, and 5th, the other members should make only correct responses. However, on trials 3, 4, and 6, the “other players” are programmed to display unanimously incorrect answers.

These latter three are critical because they represent a dependent measure of conformity to the group, calculated as the percentage of incorrect responses participants make. It’s expected that those who are ostracized will conform to the wrong answers on more trials compared to participants who are included.

Afterwards, a final questionnaire is given and includes two other dependent variables: the number of perceived throws the participant received and feelings of belonging with their respective group, assessed on a rating scale from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much).

Based on the initial narratives provided, participants are expected to rate in-group members more positively than those in the out-group. However, those who are ostracized are predicted to report receiving fewer throws and lower ratings of belonging compared to those who are included.

These results would suggest that being ignored during a computerized task—even without face-to-face communication—is enough to robustly induce feelings of social ostracism in participants.

Prior to the experiment, conduct a power analysis to recruit a sufficient number of participants for this two by three design. To begin, escort one participant at a time into the testing room.

First inform them that they are going to complete a computerized task that will compare perceptual abilities of PC vs. Mac users. Let them know that they will be interacting with other players who are simultaneously logged into the study over the internet. After answering any questions, have them sign a consent form to participate.

To determine what group participants will belong to, hand them an initial questionnaire that asks about the type of computer they typically use and requires them to write descriptions of average PC and Mac users. Note that the narratives will be used later as a manipulation check.

Randomly assign them to one of three membership compositions: in-, out-, or mixed-groups. Tell participant 1, assigned to an in-group, “The other two players you’ll interact with are also PC users.” and participant 2, an out-group member, “The other two players you’ll interact with prefer using a PC.”.

Now, before leaving the room, start the Cyberball game on the computer. While both groups are initially included in throwing the ball, starting on the fifth throw, those randomly assigned to the ostracism condition are excluded compared to those who remain included.

When the game has finished, enter the room and launch the second part of the study, a perception task, but continue to let the participant believe that this is the primary experiment.

Instruct them to click on the spinning wheel to determine their respondent number, even though the wheel is rigged to always stop at the 6th position. Continue to discuss the task and walk-through an example. Explain that on each trial, they will see a simple shape for 5 s, after which it disappears, and then reappears embedded within one of six complex figures.

For a correct response, ask them to identify the one that contains the original shape by clicking the corresponding button. Critically, explain that since they are respondent 6, they must wait their turn to respond in sequential order. Then, leave the room.

After the participant has completed the six trials in the perception task, both critical and non-critical, re-enter the room and have them complete the post-experimental questionnaire, which includes measures related to the number of perceived throws the participant received and feelings of belonging on a 9-point scale.

Finally, fully debrief participants regarding the purpose and procedures of the study by explaining the ostracism manipulations, the computer-generated partners, and the conformity ruse.

After organizing all the data, create three separate graphs for each variable. First plot the averaged perceived percentage of throws across group membership conditions, separated by inclusion and ostracism.

Similarly plot the averaged scores related to feelings of belonging, as well as the percentage of trials that participants conformed on during the critical ones.

Compared to participants who were included, those who were ostracized reported receiving fewer throws, lower feelings of belonging, and conformed on a higher percentage of trials.

While the effects of group membership were not as clear, notable interactions existed for the first two measures: individuals in the in-group condition did not significantly differ between the inclusion and ostracism groups.

However, participants who were ostracized in the in-group still conformed significantly more than individuals who were included.

Overall, these results are striking given that players were not directly communicating face to face, yet the momentary exclusion produced robust affective and behavioral consequences.

Now that you are familiar with how to induce feelings of ostracism even without direct communication, let’s look at additional ways to investigate this powerful social phenomenon, including the underlying neural responses and downstream behavioral consequences.

Ostracism is apparent across all age groups. From social exclusion on the playground, to romantic rejection as an adult, this social phenomenon threatens our human need feel included.

Researchers have found that the pain of ostracism is less intense in older adults than in young, which may suggest that as we get older, we focus more on close social partners and have less concern about exclusion from strangers.

Further, the reactions to being ostracized can have many variants. Researchers have identified that while some individuals feel the need to ingratiate themselves to their ostracizer, others can become more aggressive in the response to the exclusion in an attempt to feel more in control.

Alternatively, it can cause an individual to feel depressed and alienated, with a negative impact on their self-esteem. This suggests that while ostracism leaves no trace of physical pain, the affective impact of social pain is strong.

Lastly, this task has also been used in conjunction with functional magnetic resonance imaging to pinpoint the neural correlates underlying the feelings of ostracism.

Researchers found that the anterior cingulate cortex, the ACC, and right ventromedial prefrontal cortex, vmPFC, were more active during exclusion. However, each region showed opposite correlations with distress. Such findings suggest that the vmPFC regulates the distress of social exclusion by disrupting activity in the ACC.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on ostracism. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design, conduct, and analyze an experiment to study just how this social phenomenon impacts feelings of belonging and promotes conformity into groups in which individuals were excluded from.

Thanks for watching!