水サンプル中の レプトスピラ 検出のためのポリメラーゼ連鎖反応とドットブロットハイブリダイゼーション

Summary

この研究では、水サンプル中の3つの主要なクレードから レプトスピラ を検出するために、ドットブロットアプリケーションを設計しました。この方法により、ジゴキシゲニン標識プローブによって特異的に標的とされる最小限のDNA量を同定でき、抗ジゴキシゲニン抗体によって容易に検出されます。このアプローチは、スクリーニングの目的にとって貴重で満足のいくツールです。

Abstract

ドットブロットは、キャリアDNAの存在下でプローブハイブリダイゼーションによって特異的に標的とされる最小限の量のDNAの同定を可能にする、シンプル、高速、高感度、および汎用性の高い技術です。これは、ナイロン膜などの不活性固体支持体に既知の量のDNAを、ドットブロット装置を利用して電気泳動分離なしで転写することに基づいています。ナイロン膜は、高い核酸結合能(400μg / cm2)、高強度、および正または中性に帯電しているという利点があります。使用されるプローブは、ジゴキシゲニン(DIG)で標識された18〜20塩基の非常に特異的なssDNAフラグメントです。プローブは レプトスピラ DNAと結合します。プローブが標的DNAとハイブリダイズすると、抗ジゴキシゲニン抗体によって検出され、X線フィルムで明らかになった発光によって簡単に検出できます。発光のあるドットは、目的のDNA断片に対応します。この方法では、プローブの非同位体標識を採用しており、半減期が非常に長い場合があります。この標準的な免疫標識の欠点は、同位体プローブよりも感度が低いことです。それにもかかわらず、ポリメラーゼ連鎖反応(PCR)とドットブロットアッセイを組み合わせることで軽減されます。このアプローチにより、ターゲット配列の濃縮とその検出が可能になります。さらに、よく知られている標準の段階希釈と比較した場合の定量的アプリケーションとして使用できます。ここでは、水サンプル中の3つの主要なクレードから レプトスピラ を検出するためのドットブロットアプリケーションを紹介します。この方法論は、遠心分離によって濃縮された大量の水に適用して、レプトスパイラルDNAの存在の証拠を提供することができます。これは、一般的なスクリーニング目的にとって貴重で満足のいくツールであり、水中に存在する可能性のある他の培養不可能な細菌に使用できるため、生態系の理解が向上します。

Introduction

ヒトのレプトスピラ症は、主に環境源に由来します1,2。湖、川、小川でのレプトスピラの存在は、野生生物、および最終的にこれらの水域と接触する可能性のある家畜および生産動物の間でのレプトスピラ症の伝播の指標です1,3,4。さらに、レプトスピラは、下水、停滞水、水道水などの非天然水源で確認されています5,6。

レプトスピラは世界中に分布する細菌であり7,8、その保存と伝播における環境の役割はよく認識されています。レプトスピラは、さまざまなpHとミネラル9の飲料水、および天然の水域1で生存できます。また、蒸留水10中で長期間生存することができ、一定のpH(7.8)下では、最大152日間生存する可能性があります11。さらに、レプトスピラは、過酷な条件を生き残るために細菌コンソーシアムで相互作用する可能性があります12,13。アゾスピリルムやスフィンゴモナスを含む淡水中のバイオフィルムの一部である可能性があり、49°Cを超える温度に成長し、耐えることさえできます14,15。また、浸水した土壌で増殖し、最大379日間生存し続けることができ16、17,18年もの間病気を引き起こす能力を維持します。しかし、水域内の生態学と、それが水域内でどのように分布しているかについてはほとんど知られていません。

その発見以来、レプトスピラ属の研究は血清学的検査に基づいていました。分子技術がこのスピロヘータの研究でより普及したのは今世紀になってからでした。ドットブロットは、(1)16S rRNAおよび単純配列反復(ISSR)に基づく同位体プローブ19,20、(2)尿に適用されるヒトレプトスピラ症に対するナノゴールドベースの免疫測定法21、または(3)ウシ尿サンプル22に対する抗体ベースのアッセイとして、その同定にはほとんど使用されていません.この技術は、もともと同位体プローブに基づいていたため、使用されなくなりました。しかし、PCRと組み合わせることで、より高度な結果が得られることはよく知られた技術であり、非同位体プローブを使用しているため安全であると考えられています。PCRは、サンプル中に微量に見られる可能性のある特定のDNA断片を増幅することにより、レプトスピラDNAの濃縮に重要な役割を果たします。各PCRサイクル中に、標的DNA断片の量が反応で2倍になります。反応の終わりに、アンプリコンは100万倍以上になりました23。PCRによって増幅された生成物は、アガロース電気泳動では見えないことが多いが、ドットブロット24,25,26のDIG標識プローブとの特異的ハイブリダイゼーションによって見えるようになる。

ドットブロット法は、シンプルで堅牢で、多数のサンプルに適しているため、リソースが限られているラボでも利用することができます。これは、(1)口腔細菌27、(2)食物や糞便などの他のサンプルタイプ28、および(3)培養不可能な細菌の同定29を含むさまざまな細菌研究で採用されており、多くの場合、他の分子技術と一致しています。ドットブロット技術によって提供される利点の中には、(1)メンブレンは高い結合能力を持ち、200μg/ cm2 以上の核酸および最大400μg / cm2に結合することができる。(2)ドットブロットの結果は、特別な機器を必要とせずに視覚的に解釈でき、(3)室温(RT)で何年も保存することができます。

レプトスピラ属は、病原性、中間性、および腐生性のクレードに分類されています30,31。これらのクレード間の区別は、lipL41、lipL32、および16S rRNAなどの特定の遺伝子に基づいて達成できます。LipL32は病原性クレードに存在し、さまざまな血清学的および分子的ツールで高い感受性を示しますが、腐生植物種には存在しません21。ハウスキーピング遺伝子lipL41は、その安定した発現で知られており、分子技術32に使用され、16S rRNA遺伝子はそれらの分類に利用されています。

この方法は、遠心分離によって濃縮された大量の水に適用できます。これにより、水域内のさまざまなポイントと深さを評価して、レプトスパイラルDNAの存在とそれが属するクレードを検出できます。このツールは、生態学的および一般的なスクリーニング目的の両方に有用であり、水中に存在する可能性のある他の培養不可能な細菌を検出するためにも使用できます。

さらに、PCRおよびドットブロットアッセイは、高度な機器や高価な機器を持たないラボであっても、幅広いラボにとって技術的および経済的に手頃な価格です。この研究は、ジゴキシゲニンベースのドットブロットを、天然の水域から収集された水サンプル中の3つの レプトスピラ クレードの同定に適用することを目的としています。

細菌株

12の レプトスピラ 血清型動物(Autumnalis、Bataviae、Bratislava、Canicola、Celledoni、Grippothyphosa、Hardjoprajitno、Icterohaemorrhagiae、Pomona、Pyrogenes、Tarassovi、およびWolffi)がこの研究に含まれました。これらの血清型は、メキシコ国立自治大学獣医学部微生物学・免疫学科のコレクションの一部であり、現在、微小凝集試験(MAT)に使用されています。

すべての レプトスピラ 血清型動物はEMJHで培養され、それらのDNAは市販のDNA抽出キットを使用して抽出されました( 材料の表を参照)。12種類の血清型のゲノムDNA混合物を 、レプトスピラ 病原性クレードのポジティブコントロールとして使用した。 レプトスピラ 中間体クレードのポジティブコントロールとして、 Leptospira fainei serovar Hurstbridge株BUT6由来のゲノムDNAが含まれ、 レプトスピラ 腐生菌クレードのポジティブコントロールとして、 Leptospira biflexa serovar Patoc Patoc株Patoc IのゲノムDNAも含まれていた。

ネガティブコントロールは、空のプラスミド、非血縁細菌(Ureaplasma urealyticum、黄色ブドウ球菌、Brucella abortus、Salmonella typhimurium、赤痢菌、肺炎桿菌、Acinetobacter baumannii、 および 大腸菌 )のDNA、および非テンプレートコントロールとして機能するPCRグレードの水で構成されていました。

水のサンプル

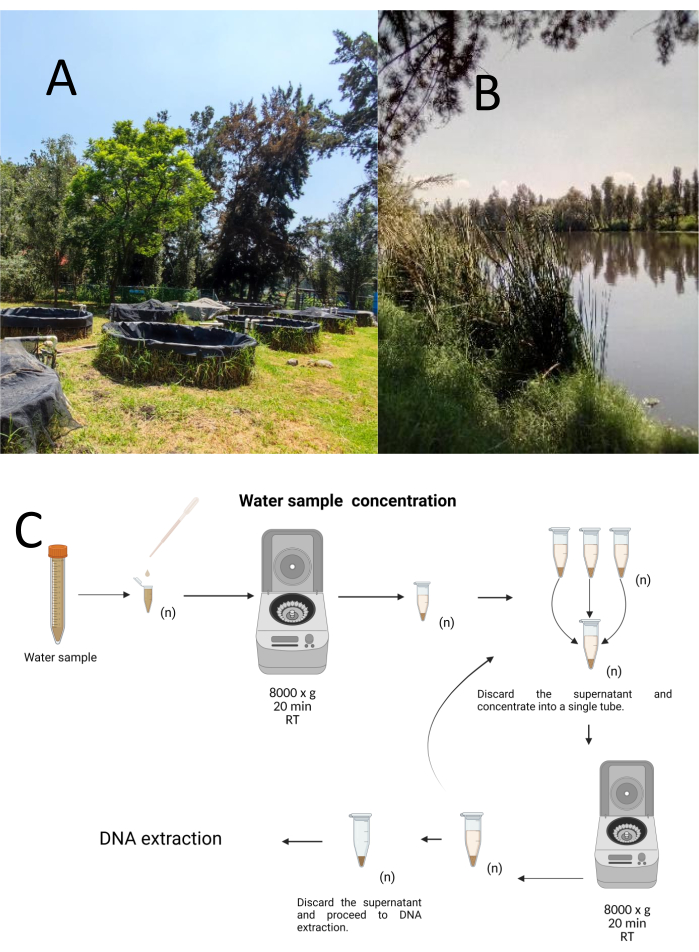

12の試験グラブサンプルは、Cuemanco Biological and Aquaculture Research Center(CIBAC)から層別でたらめなサンプリング法を使用して収集されました(19°16’54” N 99°6’11” W)。これらのサンプルは、表層、10、30 cmの3つの深さで採取されました(図1A、B)。水の収集手順は、絶滅危惧種や保護種に影響を与えませんでした。各サンプルは、滅菌済みの15 mL微量遠心チューブに収集しました。サンプルを採取するために、各チューブを水に静かに沈め、選択した深さで充填してから密封しました。サンプルは22°Cに維持され、処理のためにすぐに実験室に運ばれました。

各サンプルは、滅菌済みの1.5 mLマイクロ遠心チューブに8000 x g で20分間遠心分離して濃縮しました。このステップは、すべてのサンプルが1本のチューブに濃縮されるまで繰り返され、DNA抽出に使用されました(図1C)。

図1:遠心分離による水サンプルの濃度(A)採水池、(B)自然の流れ。(C)遠心分離ベースの水サンプル処理を必要な回数だけ繰り返します(n)。この図の拡大版を見るには、ここをクリックしてください。

DNA抽出

全DNAは、製造元の指示に従って市販のゲノムDNAキットを使用して単離しました( 材料の表を参照)。DNA抽出物を20μLの溶出緩衝液中で溶出し、DNA濃度をUV分光光度計で260〜280nmで測定し、使用するまで4°Cで保存した。

PCR増幅

PCRターゲットは、16個のS rRNA、lipL41、およびlipL32遺伝子であり、レプトスピラ属のDNAを同定し、病原性、腐生性、および中間体の3つのクレードを区別することができます。プライマーとプローブの設計は、Ahmedら、Azaliら、Bourhyら、Weissら、およびBrangerらによる以前の研究に基づいていました33,34,35,36,37。各プローブ、プライマー、および増幅フラグメントの配列は、表1に記載され、参照配列とのアラインメントは、補足ファイル1、補足ファイル2、補足ファイル3、補足ファイル4、および補足ファイル5に記載されている。PCR試薬とサーモサイクル条件は、プロトコルのセクションに記載されています。

増幅産物は、TAE(40 mM Tris 塩基、20 mM 酢酸、1 mM EDTA、pH 8.3)中の 1% アガロースゲル上で電気泳動分離し、エチジウムブロマイド検出を行い、エチジウムブロマイド検出を行い、補足図 1 に示すように可視化しました。各血清型から得られたゲノムDNAは、病原性レプトスピラのL.インターロガン(4, 691, 184 bp)38、腐生性レプトスピラのL. biflexa(3, 956, 088 bp)39のゲノムサイズに基づいて、各PCR反応において6 x 106から1 x 104ゲノム当量コピー(GEq)の範囲の濃度で使用されました。 L. fainei serovar Hurstbridge株BUT6(4、267、324 bp)のゲノムサイズ(アクセッション番号AKWZ00000000.2)。

プローブの感度は、各実験で各病原性血清型、 L. biflexa serovar Patoc Patoc I株、および L. fainei serovar Hurstbridge株BUT6のDNAで評価されました。PCRおよびドットブロットハイブリダイゼーションアッセイの特異性を評価するために、非血縁細菌由来のDNAを含めました。

表1:レプトスピラの病原性、腐生菌、および中間クレードを同定するための産物を増幅するためのPCRプライマーおよびプローブ。この表をダウンロードするには、ここをクリックしてください。

ドットブロットハイブリダイゼーションアッセイ

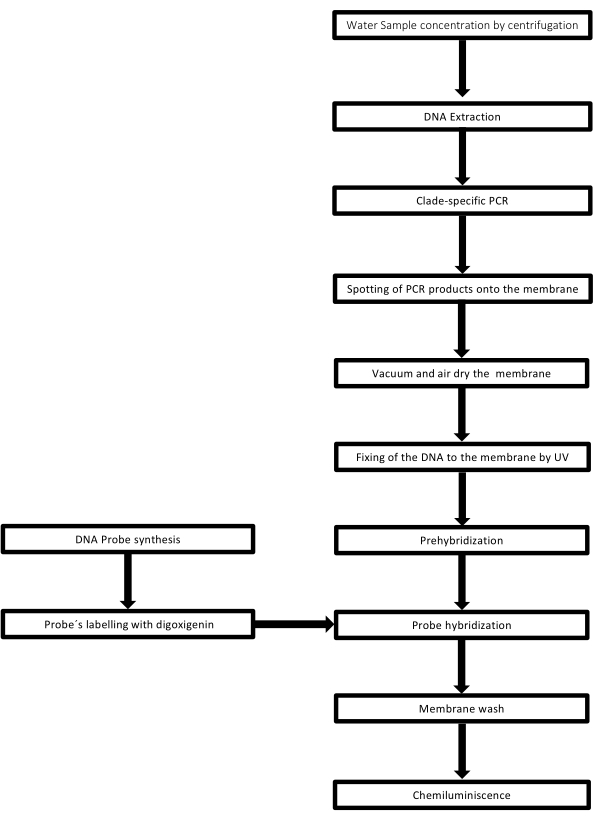

DNAサンプルを入れる穴がドット状になっており、真空吸引で所定の位置に固定するように吸引すると、この形状になることからドットブロットと呼ばれる手法です。この手法は、Kafatos et al.40によって開発されました。この技術により、各PCR陽性サンプル中のレプトスピラを半定量化できます。プロトコルは、室温でNaOH 0.4Mによる変性で構成され、6 x 106〜104レプトスパイアに対応する30ng〜0.05ngのレプトスピラDNAを含むサンプルを、96ウェルドットブロット装置でナイロンメンブレンにブロットします。固定化後、DNAは120mJのUV光にさらされることによって膜に結合します。各DNAプローブは、3’末端の末端トランスフェラーゼ触媒ステップによってジゴキシゲニン-11dUTPと結合される(ジゴキシゲニンは、レポーターとして使用されるジギタリス・プルプレアから得られる植物ステロイドである41)。標識されたDNAプローブ(50 pmol)を特定の温度で標的DNAに厳密にハイブリダイズした後、DNAハイブリッドは、その基質CSPDと共有結合した抗ジゴキシゲニンアルカリホスファターゼ抗体との化学発光反応によって可視化されます。発光は、X線フィルムへの曝露によって捕捉されます(図2)。

図2:PCRドットブロットアッセイの手順のステップ。 この 図の拡大版を見るには、ここをクリックしてください。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

ドットブロット技術の重要なステップには、(1)DNA固定化、(2)非相同DNAによる膜上の自由結合部位のブロッキング、(3)アニーリング条件下でのプローブと標的フラグメントとの間の相補性、(4)非ハイブリダイズプローブの除去、および(5)レポーター分子の検出が含まれます41。

PCR−ドット−ブロットは、ある種の限界を有し、例えば、この技術は、ハイブ…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

メキシコ国立自治大学獣医学部微生物学・免疫学科のレプトスピラコレクションに恩義を感じています。参照レプトスピラ株の寛大な寄付に感謝します。Leptospira fainei serovar Hurstbridge株BUT6およびLeptospira biflexa serovar Patoc株Patoc IからAlejandro de la Peña Moctezuma博士へ。CIBACコーディネーターのホセ・アントニオ・オカンポ・セルバンテス博士と、後方支援をしてくれた職員に感謝します。EDTは、メトロポリタン自治大学キャンパスクアジマルパの学部生向けのターミナルプロジェクトプログラムの下にありました。図1、図3から図9の作成にソフトウェア Biorender.com を認めます。

Materials

| REAGENTS | |||

| Purelink DNA extraction kit | Invitrogen | K182002 | |

| Gotaq Flexi DNA Polimerase (End-Point PCR Taq polymerase kit) | Promega | M3001 | |

| Whatman filter paper, grade 1, | Merk | WHA1001325 | |

| Nylon Membranes, positively charged Roll 30cm x 3 m | Roche | 11417240001 | |

| Anti-Digoxigenin-AP, Fab fragments Sheep Polyclonal Primary-antibody | Roche | 11093274910 | |

| Medium Base EMJH | Difco | S1368JAA | |

| Leptospira Enrichment EMJH | Difco | BD 279510 | |

| Blocking Reagent | Roche | 11096176001 | |

| CSPD ready to use Disodium 3-(4-methoxyspiro {1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro) tricyclo [3.3.1.13,7] decan}8-4-yl) phenyl phosphate | Merk | 11755633001 | |

| Deoxyribonucleic acid from herring sperm | Sigma Aldrich | D3159 | |

| Developer Carestream | Carestream Health Inc | GBX5158621 | |

| Digoxigenin-11-ddUTP | Roche | 11363905910 | |

| EDTA, Disodium Salt (Dihydrate) | Promega | H5032 | |

| Ficoll 400 | Sigma Aldrich | F8016 | |

| Fixer Carestream | Carestream Health Inc | GBX 5158605 | |

| Lauryl sulfate Sodium Salt (Sodium dodecyl sulfate; SDS) C12H2504SNa | Sigma Aldrich | L5750 | |

| N- Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt CH3(CH2)10CON(CH3) CH2COONa | Sigma Aldrich | L-9150 | It is an anionic surfactant |

| Polivinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40) | Sigma Aldrich | PVP40 | |

| Polyethylene glycol Sorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20) | Sigma Aldrich | 9005-64-5 | |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Sigma Aldrich | 7647-14-5 | |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) | Sigma Aldrich | 151-21-3 | |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Sigma Aldrich | 1310-73-2 | |

| Sodium phosphate dibasic (NaH2PO4) | Sigma-Aldrich | 7558-79-4 | |

| Terminal transferase, recombinant | Roche | 3289869103 | |

| Tris hydrochloride (Tris HCl) | Sigma-Aldrich | 1185-53-1 | |

| SSPE 20X | Sigma-Aldrich | S2015-1L | It can be Home-made following Supplementary File 6 |

| Primers | Sigma-Aldrich | On demand | Follow table 1 |

| Probes | Sigma-Aldrich | On demand | Follow table 1 |

| Equipment | |||

| Nanodrop™ One Spectrophotometer | Thermo-Scientific | ND-ONE-W | |

| Refrigerated microcentrifuge Sigma 1-14K, suitable for centrifugation of 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes at 14,000 rpm | Sigma-Aldrich | 1-14K | |

| Disinfected adjustable pipettes, range 2-20 µl, 20-200 µl | Gilson | SKU:F167360 | |

| Disposable 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes (autoclaved) | Axygen | MCT-150-SP | |

| Disposable 600 µl microcentrifuge tubes (autoclaved) | Axygen | 3208 | |

| Disposable Pipette tips 1-10 µl | Axygen | T-300 | |

| Disposable Pipette tips 1-200 µl | Axygen | TR-222-Y | |

| Dot-Blot apparatus Bio-Dot | BIORAD | 1706545 | |

| Portable Hergom Suction | Hergom | 7E-A | |

| Scientific Light Box (Visible-light PH90-115V) | Hoefer | PH90-115V | |

| UV Crosslinker | Hoefer | UVC-500 | |

| Thermo Hybaid PCR Express Thermocycler | Hybaid | HBPX110 | |

| Radiographic cassette with IP Plate14 X 17 | Fuji |

References

- Bierque, E., Thibeaux, R., Girault, D., Soupé-Gilbert, M. E., Goarant, C. A systematic review of Leptospira in water and soil environments. PLOS One. 15 (1), e0227055 (2020).

- Haake, D. A., Levett, P. N. Leptospirosis in humans. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 387, 65-97 (2015).

- Tripathy, D. N., Hanson, L. E. Leptospires from water sources at Dixon Springs Agricultural Center. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 9 (3), 209-212 (1973).

- Smith, D. J., Self, H. R. Observations on the survival of Leptospira australis A in soil and water. The Journal of Hygiene. 53 (4), 436-444 (1955).

- Karpagam, K. B., Ganesh, B. Leptospirosis: a neglected tropical zoonotic infection of public health importance-an updated review. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 39 (5), 835-846 (2020).

- Casanovas-Massana, A., et al. Spatial and temporal dynamics of pathogenic Leptospira in surface waters from the urban slum environment. Water Research. 130, 176-184 (2018).

- Costa, F., et al. Global morbidity and mortality of Leptospirosis: A systematic review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (9), e0003898 (2015).

- Mwachui, M. A., Crump, L., Hartskeerl, R., Zinsstag, J., Hattendorf, J. Environmental and behavioural determinants of Leptospirosis transmission: A systematic review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (9), e0003843 (2015).

- Andre-Fontaine, G., Aviat, F., Thorin, C. Waterborne Leptospirosis: Survival and preservation of the virulence of pathogenic Leptospira spp. in fresh water. Current Microbiology. 71 (1), 136-142 (2015).

- Trueba, G., Zapata, S., Madrid, K., Cullen, P., Haake, D. Cell aggregation: A mechanism of pathogenic Leptospira to survive in freshwater. International Microbiology: the Official Journal of the Spanish Society for Microbiology. 7 (1), 35-40 (2004).

- Smith, C. E., Turner, L. H. The effect of pH on the survival of leptospires in water. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 24 (1), 35-43 (1961).

- Barragan, V. A., et al. Interactions of Leptospira with environmental bacteria from surface water. Current Microbiology. 62 (6), 1802-1806 (2011).

- Abdoelrachman, R. Comparative investigations into the influence of the presence of bacteria on the life of pathogenic and apathogenic leptospirae. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 13 (1), 21-32 (1947).

- Singh, R., et al. Microbial diversity of biofilms in dental unit water systems. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (6), 3412-3420 (2003).

- Kumar, K. V., Lall, C., Raj, R. V., Vedhagiri, K., Vijayachari, P. Coexistence and survival of pathogenic leptospires by formation of biofilm with Azospirillum. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 91 (6), 051 (2015).

- Yanagihara, Y., et al. Leptospira Is an environmental bacterium that grows in waterlogged soil. Microbiology Spectrum. 10 (2), 0215721 (2022).

- Gillespie, R. W., Ryno, J. Epidemiology of leptospirosis. American Journal of Public Health and Nation’s Health. 53 (6), 950-955 (1963).

- Bierque, E., et al. Leptospira interrogans retains direct virulence after long starvation in water. Current Microbiology. 77 (10), 3035-3043 (2020).

- Zhang, Y., Dai, B. Marking and detection of DNA of leptospires in the dot-blot and situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences. 23 (4), 353-435 (1992).

- Mérien, F., Amouriaux, P., Perolat, P., Baranton, G., Saint Girons, I. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of Leptospira spp. in clinical samples. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 30 (9), 2219-2224 (1992).

- Veerapandian, R., et al. Silver enhanced nano-gold dot-blot immunoassay for leptospirosis. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 156, 20-22 (2019).

- Junpen, S., et al. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody-based dot-blot ELISA for detection of Leptospira spp in bovine urine samples. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 66 (5), 762-766 (2005).

- Ishmael, F. T., Stellato, C. Principles and applications of polymerase chain reaction: basic science for the practicing physician. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: Official Publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 101 (4), 437-443 (2008).

- Boerner, B., Weigelt, W., Buhk, H. J., Castrucci, G., Ludwig, H. A sensitive and specific PCR/Southern blot assay for detection of bovine herpesvirus 4 in calves infected experimentally. Journal of Virological Methods. 83 (1-2), 169-180 (1999).

- Curry, E., Pratt, S. L., Kelley, D. E., Lapin, D. R., Gibbons, J. R. Use of a Combined duplex PCR/Dot-blot assay for more sensitive genetic characterization. Biochemistry Insights. 1, 35-39 (2008).

- Pilatti, M. M., Ferreira, S. d. e. A., de Melo, M. N., de Andrade, A. S. Comparison of PCR methods for diagnosis of canine visceral leishmaniasis in conjunctival swab samples. Research in Veterinary Science. 87 (2), 255-257 (2009).

- Conrads, G., et al. PCR reaction and dot-blot hybridization to monitor the distribution of oral pathogens within plaque samples of periodontally healthy individuals. Journal of Periodontology. 67 (10), 994-1003 (1996).

- Langa, S., et al. Differentiation of Enterococcus faecium from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus strains by PCR and dot-blot hybridisation. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 88 (2-3), 197-200 (2003).

- Francesca, C., Lucilla, I., Marco, F., Giuseppe, C., Marisa, M. Identification of the unculturable bacteria Candidatus arthromitus in the intestinal content of trouts using dot-blot and Southern blot techniques. Veterinary Microbiology. 156 (3-4), 389-394 (2012).

- Arent, Z., Pardyak, L., Dubniewicz, K., Plachno, B. J., Kotula-Balak, M. Leptospira taxonomy: then and now. Medycyna Weterynaryjna. 78 (10), 489-496 (2022).

- Thibeaux, R., et al. Biodiversity of environmental Leptospira: Improving identification and revisiting the diagnosis. Frontiers in Microbiology. 9, 816 (2018).

- Carrillo-Casas, E. M., Hernández-Castro, R., Suárez-Güemes, F., de la Peña-Moctezuma, A. Selection of the internal control gene for real-time quantitative RT-PCR assays in temperature treated Leptospira. Current Microbiology. 56 (6), 539-546 (2008).

- Azali, M. A., Yean Yean, C., Harun, A., Aminuddin Baki A, N. N., Ismail, N. Molecular characterization of Leptospira spp. in environmental samples from North-Eastern Malaysia revealed a pathogenic strain, Leptospira alstonii. Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2016, 2060241 (2016).

- Ahmed, N., et al. Multilocus sequence typing method for identification and genotypic classification of pathogenic Leptospira species. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 5, 28 (2006).

- Bourhy, P., Collet, L., Brisse, S., Picardeau, M. Leptospira mayottensis sp. nov., a pathogenic species of the genus Leptospira isolated from humans. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 64, 4061-4067 (2014).

- Weiss, S., et al. An extended Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) scheme for rapid direct typing of Leptospira from clinical samples. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (9), e0004996 (2016).

- Branger, C., et al. Polymerase chain reaction assay specific for pathogenic Leptospira based on the gene hap1 encoding the hemolysis-associated protein-1. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 243 (2), 437-445 (2005).

- Ren, S. X., et al. Unique physiological and pathogenic features of Leptospira interrogans revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 422 (6934), 888-893 (2003).

- Picardeau, M., et al. Genome sequence of the saprophyte Leptospira biflexa provides insights into the evolution of Leptospira and the pathogenesis of leptospirosis. PLOS One. 3 (2), e1607 (2008).

- Kafatos, F. C., Jones, C. W., Efstratiadis, A. Determination of nucleic acid sequence homologies and relative concentrations by a dot hybridization procedure. Nucleic Acids Research. 7 (6), 1541-1552 (1979).

- Bhat, A. I., Rao, G. P. Dot-blot hybridization technique. Characterization of Plant Viruses. , 303-321 (2020).

- Yadav, J. P., Batra, K., Singh, Y., Singh, M. Comparative evaluation of indirect-ELISA and Dot-blot assay for serodetection of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae antibodies in poultry. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 189, 106317 (2021).

- Malinen, E., Kassinen, A., Rinttilä, T., Palva, A. Comparison of real-time PCR with SYBR Green I or 5′-nuclease assays and dot-blot hybridization with rDNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes in quantification of selected faecal bacteria. Microbiology. 149, 269-277 (2003).

- Wyss, C., et al. Treponema lecithinolyticum sp. nov., a small saccharolytic spirochaete with phospholipase A and C activities associated with periodontal diseases. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 49, 1329-1339 (1999).

- Shah, J. S., I, D. C., Ward, S., Harris, N. S., Ramasamy, R. Development of a sensitive PCR-dot-blot assay to supplement serological tests for diagnosing Lyme disease. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 37 (4), 701-709 (2018).

- Niu, C., Wang, S., Lu, C. Development and evaluation of a dot-blot assay for rapid determination of invasion-associated gene ibeA directly in fresh bacteria cultures of E. coli. Folia microbiologica. 57 (6), 557-561 (2012).

- Wetherall, B. L., McDonald, P. J., Johnson, A. M. Detection of Campylobacter pylori DNA by hybridization with non-radioactive probes in comparison with a 32P-labeled probe. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 26 (4), 257-263 (1988).

- Kolk, A. H., et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples by using polymerase chain reaction and a nonradioactive detection system. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 30 (10), 2567-2575 (1992).

- Scherer, L. C., et al. PCR colorimetric dot-blot assay and clinical pretest probability for diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in smear-negative patients. BMC Public Health. 7, 356 (2007).

- Armbruster, D. A., Pry, T. Limit of blank, limit of detection and limit of quantitation. The Clinical Biochemist Reviews. 29, S49-S52 (2008).

- Zhang, Y., Dai, B. Detection of Leptospira by dot-blot hybridization with photobiotin- and 32P-labeled DNA. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 23 (2), 130-132 (1992).

- Terpstra, W. J., Schoone, G. J., ter Schegget, J. Detection of leptospiral DNA by nucleic acid hybridization with 32P- and biotin-labeled probes. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 22 (1), 23-28 (1986).

- Shukla, J., Tuteja, U., Batra, H. V. DNA probes for identification of leptospires and disease diagnosis. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 35 (2), 346-352 (2004).

- Jiang, N., Jin, B., Dai, B., Zhang, Y. Identification of pathogenic and nonpathogenic leptospires by recombinant probes. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 26 (1), 1-5 (1995).

- Fach, P., Trap, D., Guillou, J. P. Biotinylated probes to detect Leptospira interrogans on dot-blot hybridization or by in situ hybridization. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 12 (5), 171-176 (1991).

- Huang, N., Dai, B. Assay of genomic DNA homology among strains of different virulent leptospira by DNA hybridization. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 23 (2), 122-125 (1992).

- Dong, X., Dai, B., Chai, J. Homology study of leptospires by molecular hybridization. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 23 (1), 1-4 (1992).

- Komminoth, P. Digoxigenin as an alternative probe labeling for in situ hybridization. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology: The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, part B. 1 (2), 142-150 (1992).

- Saengjaruk, P., et al. Diagnosis of human leptospirosis by monoclonal antibody-based antigen detection in urine. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (2), 480-489 (2002).

- Okuda, M., et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of canine Leptospira antibodies using recombinant OmpL1 protein. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 67 (3), 249-254 (2005).

- Suwimonteerabutr, J., et al. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody-based dot-blot ELISA for detection of Leptospira spp in bovine urine samples. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 66 (5), 762-766 (2005).

- Kanagavel, M., et al. Peptide-specific monoclonal antibodies of Leptospiral LigA for acute diagnosis of leptospirosis. Scientific reports. 7 (1), 3250 (2017).

- Levett, P. N. Leptospirosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 14 (2), 296-326 (2001).

- Monahan, A. M., Callanan, J. J., Nally, J. E. Proteomic analysis of Leptospira interrogans shed in urine of chronically infected hosts. Infection and Immunity. 76 (11), 4952-4958 (2008).

- Rojas, P., et al. Detection and quantification of leptospires in urine of dogs: a maintenance host for the zoonotic disease leptospirosis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 29 (10), 1305-1309 (2010).