Enhanced Oil Recovery using a Combination of Biosurfactants

Summary

We illustrate the methods involved in screening and identification of the biosurfactant producing microbes. Methods for chromatographic characterization and chemical identification of the biosurfactants, determining the industrial applicability of the biosurfactant in enhancing residual oil recovery are also presented.

Abstract

Biosurfactants are surface-active compounds capable of reducing the surface tension between two phases of different polarities. Biosurfactants have been emerging as promising alternatives to chemical surfactants due to less toxicity, high biodegradability, environmental compatibility and tolerance to extreme environmental conditions. Here, we illustrate the methods used for screening of microbes capable of producing biosurfactants. The biosurfactant producing microbes were identified using drop collapse, oil spreading, and emulsion index assays. Biosurfactant production was validated by determining the reduction in surface tension of the media due to growth of the microbial members. We also describe the methods involved in characterization and identification of biosurfactants. Thin layer chromatography of the extracted biosurfactant followed by differential staining of the plates was performed to determine the nature of the biosurfactant. LCMS, 1H NMR, and FT-IR were used to chemically identify the biosurfactant. We further illustrate the methods to evaluate the application of the combination of produced biosurfactants for enhancing residual oil recovery in a simulated sand pack column.

Introduction

Biosurfactants are the amphipathic surface-active molecules produced by microorganisms that have the capacity to reduce the surface and the interfacial tension between two phases1. A typical biosurfactant contains a hydrophilic part that is usually composed of a sugar moiety or a peptide chain or hydrophilic amino acid and a hydrophobic part that is made up of a saturated or unsaturated fatty acid chain2. Due to their amphipathic nature, biosurfactants assemble at the interface between the two phases and reduce the interfacial tension at the boundary, which facilitates the dispersion of one phase into the other1,3. Various types of biosurfactants that have been reported so far include glycolipids in which carbohydrates are linked to long chain aliphatic or hydroxy-aliphatic acids via ester bonds (e.g., rhamnolipids, trehalolipids and sophorolipids), lipopeptides in which lipids are attached to polypeptide chains (e.g., surfactin and lichenysin), and polymeric biosurfactants that are usually composed of polysaccharide- protein complexes (e.g., emulsan, liposan, alasan and lipomannan)4. Other types of biosurfactants produced by the microorganisms include fatty acids, phospholipids, neutral lipids, and particulate biosurfactants5. The most studied class of biosurfactants is glycolipids and among them most of the studies have been reported on rhamnolipids6. Rhamnolipids contain one or two molecules of rhamnose (which form the hydrophilic part) linked to one or two molecules of long chain fatty acid (usually hydroxy-decanoic acid). Rhamnolipids are primary glycolipids reported first from Pseudomonas aeruginosa7.

Biosurfactants have been gaining increasing focus as compared to their chemical counterparts due to various unique and distinctive properties that they offer8. These include higher specificity, lower toxicity, greater diversity, ease of preparation, higher biodegradability, better foaming, environmental compatibility and activity under extreme conditions9. Structural diversity of the biosurfactants (Figure S1) is another advantage that gives them an edge over the chemical counterparts10. They are generally more effective and efficient at lower concentrations as their critical micelle concentration (CMC) is usually several times lower than chemical surfactants11. They have been reported to be highly thermostable (up to 100 °C) and can tolerate higher pH (up to 9) and high salt concentrations (up to 50 g/L)12 thereby offer several advantages in industrial processes, which require exposure to extreme conditions13. Biodegradability and lower toxicity make them suitable for environmental applications such as bioremediation. Because of the advantages that they offer, they have been getting increased attention in various industries like food, agricultural, detergent, cosmetic and petroleum industry11. Biosurfactants have also gained a lot of attention in oil remediation for removal of petroleum contaminants and toxic pollutants14.

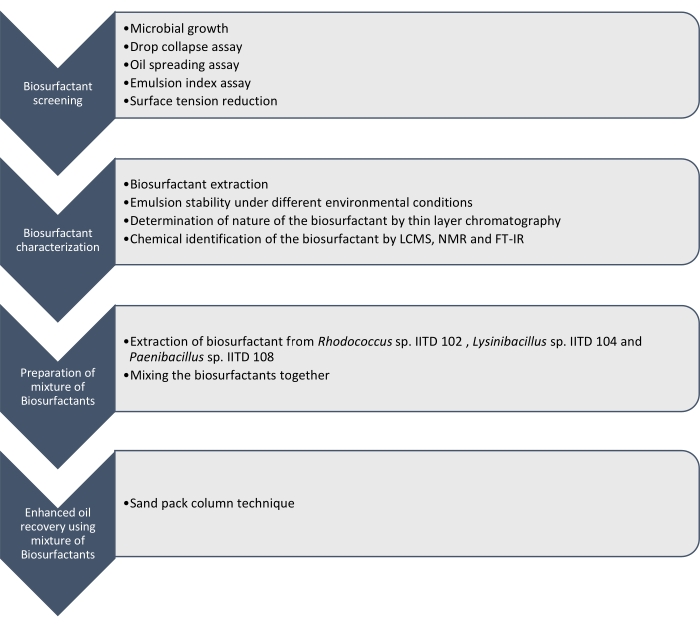

Here we report the production, characterization, and application of biosurfactants produced by Rhodococcus sp. IITD102, Lysinibacillus sp. IITD104, and Paenibacillus sp. IITD108. The steps involved in screening, characterization, and application of a combination of biosurfactants for enhanced oil recovery are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A method for enhanced oil recovery using a combination of Biosurfactants. The stepwise work flow is shown. The work was carried out in four steps. First the microbial strains were cultured and screened for the production of biosurfactant by various assays, which included drop collapse assay, oil spreading assay, emulsion index assay, and surface tension measurement. Then, the biosurfactants were extracted from the cell-free broth and their nature was identified using thin layer chromatography and they were further identified using LCMS, NMR, and FT-IR. In the next step, the extracted biosurfactants were mixed together and the potential of the resulting mixture for enhanced oil recovery was determined using the sand pack column technique. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Screening of these microbial strains to produce biosurfactants was done by drop collapse, oil spreading, emulsion index assay and determination of reduction in the surface tension of the cell-free medium due to growth of the microbes. The biosurfactants were extracted, characterized, and chemically identified by LCMS, 1H NMR, and FT-IR. Finally, a mixture of biosurfactants produced by these microbes was prepared and was used to recover the residual oil in a simulated sand pack column.

The present study only illustrates the methods involved in screening, identification, structural characterization, and application of the biosurfactant combination on enhancing residual oil recovery. It does not provide a detailed functional characterization of the biosurfactants produced by the microbial strains15,16. Various experiments such as critical micelle determination, thermogravimetric analysis, surface wettability, and biodegradability are performed for detailed functional characterization of any biosurfactant. But since this paper is a methods paper, the focus is on screening, identification, structural characterization, and application of the biosurfactant combination on enhancing residual oil recovery; these experiments have not been included in this study.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

Biosurfactants are one of the most versatile group of biologically active components that are becoming attractive alternatives to chemical surfactants. They have a wide range of applications in numerous industries such as detergents, paints, cosmetics, food, pharmaceuticals, agriculture, petroleum, and water treatment due to their better wettability, lower CMC, diversified structure, and environmental friendliness18. This has led to an increased interest in discovering more microbial strains capab…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for financial support.

Materials

| 1 ml pipette | Eppendorf, Germany | G54412G | |

| 1H NMR | Bruker Avance AV-III type spectrometer,USA | ||

| 20 ul pipette | Thermo scientific, USA | H69820 | |

| Autoclave | JAISBO, India | Ser no 5923 | Jain Scientific |

| Blue flame burner | Rocker scientific, Taiwan | dragon 200 | |

| Butanol | GLR inovations, India | GLR09.022930 | |

| C18 column | Agilent Technologies, USA | 770995-902 | |

| Centrifuge | Eppendorf, Germany | 5810R | |

| Chloroform | Merck, India | 1.94506.2521 | |

| Chloroform-d | SRL, India | 57034 | |

| Falcon tubes | Tarsons, India | 546041 | Radiation sterilized polypropylene |

| FT-IR | Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA | Nicolet iS50 | |

| Fume hood | Khera, India | 47408 | Customied |

| glacial acetic acid | Merck, India | 1.93002 | |

| Glass beads | Merck, India | 104014 | |

| Glass slides | Polar industrial Corporation, USA | Blue Star | 75 mm * 25 mm |

| Glass wool | Merk, India | 104086 | |

| Hydrochloric acid | Merck, India | 1003170510 | |

| Incubator | Thermo Scientific, USA | MaxQ600 | Shaking incubator |

| Incubator | Khera, India | Sunbim | |

| Iodine resublimed | Merck, India | 231-442-4 | resublimed Granules |

| K12 –Kruss tensiometer | Kruss Scientific, Germany | K100 | |

| Laminar air flow cabnet | Thermo Scientific, China | 1300 Series A2 | |

| LCMS | Agilent Technologies, USA | 1260 Infinity II | |

| Luria Broth | HIMEDIA, India | M575-500G | Powder |

| Methanol | Merck, India | 107018 | |

| Ninhydrin | Titan Biotech Limited, India | 1608 | |

| p- anisaldehyde | Sigma, USA | 204-602-6 | |

| Petri plate | Tarsons, India | 460090-90 MM | Radiation sterilized polypropylene |

| Saponin | Merck, India | 232-462-6 | |

| Sodium chloride | Merck, India | 231-598-3 | |

| Test tubes | Borosil, India | 9800U06 | Glass tubes |

| TLC plates | Merck, India | 1055540007 | |

| Vortex | GeNei, India | 2006114318 | |

| Water Bath | Julabo, India | SW21C |

References

- Desai, J. D., Banat, I. M. Microbial production of surfactants and their commercial potential. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 61 (1), 47-64 (1997).

- Banat, I. M. Biosurfactants production and possible uses in microbial enhanced oil recovery and oil pollution remediation: a review. Bioresource Technology. 51 (1), 1-12 (1995).

- Singh, A., Van Hamme, J. D., Ward, O. P. Surfactants in microbiology and biotechnology: Part 2. Application aspects. Biotechnology Advances. 25 (1), 99-121 (2007).

- Shah, N., Nikam, R., Gaikwad, S., Sapre, V., Kaur, J. Biosurfactant: types, detection methods, importance and applications. Indian Journal of Microbiology Research. 3 (1), 5-10 (2016).

- McClements, D. J., Gumus, C. E. Natural emulsifiers-Biosurfactants, phospholipids, biopolymers, and colloidal particles: Molecular and physicochemical basis of functional performance. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 234, 3-26 (2016).

- Nguyen, T. T., Youssef, N. H., McInerney, M. J., Sabatini, D. A. Rhamnolipid biosurfactant mixtures for environmental remediation. Water Research. 42 (6-7), 1735-1743 (2008).

- Maier, R. M., Soberon-Chavez, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhamnolipids: biosynthesis and potential applications. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 54 (5), 625-633 (2000).

- Banat, I. M., Makkar, R. S., Cameotra, S. S. Potential commercial applications of microbial surfactants. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 53 (5), 495-508 (2000).

- Mulugeta, K., Kamaraj, M., Tafesse, M., Aravind, J. A review on production, properties, and applications of microbial surfactants as a promising biomolecule for environmental applications. Strategies and Tools for Pollutant Mitigation: Avenues to a Cleaner Environment. , 3-28 (2021).

- Sharma, J., Sundar, D., Srivastava, P. Biosurfactants: Potential agents for controlling cellular communication, motility, and antagonism. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 8, 727070 (2021).

- Vijayakumar, S., Saravanan, V. Biosurfactants-types, sources and applications. Research Journal of Microbiology. 10 (5), 181-192 (2015).

- Curiel-Maciel, N. F., et al. Characterization of enterobacter cloacae BAGM01 producing a thermostable and alkaline-tolerant rhamnolipid biosurfactant from the Gulf of Mexico. Marine Biotechnology. 23 (1), 106-126 (2021).

- Nikolova, C., Gutierrez, T. Biosurfactants and their applications in the oil and gas industry: current state of knowledge and future perspectives. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 9, (2021).

- Rastogi, S., Tiwari, S., Ratna, S., Kumar, R. Utilization of agro-industrial waste for biosurfactant production under submerged fermentation and its synergistic application in biosorption of Pb2. Bioresource Technology Reports. 15, 100706 (2021).

- Zargar, A. N., Lymperatou, A., Skiadas, I., Kumar, M., Srivastava, P. Structural and functional characterization of a novel biosurfactant from Bacillus sp. IITD106. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 423, 127201 (2022).

- Adnan, M., et al. Functional and structural characterization of pediococcus pentosaceus-derived biosurfactant and its biomedical potential against bacterial adhesion, quorum sensing, and biofilm formation. Antibiotics. 10 (11), 1371 (2021).

- Du Nouy, P. L. A new apparatus for measuring surface tension. The Journal of General Physiology. 1 (5), 521-524 (1919).

- Akbari, S., Abdurahman, N. H., Yunus, R. M., Fayaz, F., Alara, O. R. Biosurfactants-a new frontier for social and environmental safety: a mini review. Biotechnology Research and Innovation. 2 (1), 81-90 (2018).

- Bicca, F. C., Fleck, L. C., Ayub, M. A. Z. Production of biosurfactant by hydrocarbon degrading Rhodococcus ruber and Rhodococcus erythropolis. Revista de Microbiologia. 30 (3), 231-236 (1999).

- Kuyukina, M. S., et al. Recovery of Rhodococcus biosurfactants using methyl tertiary-butyl ether extraction. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 46 (2), 149-156 (2001).

- Philp, J., et al. Alkanotrophic Rhodococcus ruber as a biosurfactant producer. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 59 (2), 318-324 (2002).

- Mutalik, S. R., Vaidya, B. K., Joshi, R. M., Desai, K. M., Nene, S. N. Use of response surface optimization for the production of biosurfactant from Rhodococcus spp. MTCC 2574. Bioresource Technology. 99 (16), 7875-7880 (2008).

- Shavandi, M., Mohebali, G., Haddadi, A., Shakarami, H., Nuhi, A. Emulsification potential of a newly isolated biosurfactant-producing bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. strain TA6. Colloids and Surfaces B, Biointerfaces. 82 (2), 477-482 (2011).

- White, D., Hird, L., Ali, S. Production and characterization of a trehalolipid biosurfactant produced by the novel marine bacterium Rhodococcus sp., strain PML026. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 115 (3), 744-755 (2013).

- Najafi, A., et al. Interactive optimization of biosurfactant production by Paenibacillus alvei ARN63 isolated from an Iranian oil well. Colloids and Surfaces. B, Biointerfaces. 82 (1), 33-39 (2011).

- Bezza, F. A., Chirwa, E. M. N. Pyrene biodegradation enhancement potential of lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by Paenibacillus dendritiformis CN5 strain. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 321, 218-227 (2017).

- Jimoh, A. A., Lin, J. Biotechnological applications of Paenibacillus sp. D9 lipopeptide biosurfactant produced in low-cost substrates. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 191 (3), 921-941 (2020).

- Liang, T. -. W., et al. Exopolysaccharides and antimicrobial biosurfactants produced by Paenibacillus macerans TKU029. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 172 (2), 933-950 (2014).

- Mesbaiah, F. Z., et al. Preliminary characterization of biosurfactant produced by a PAH-degrading Paenibacillus sp. under thermophilic conditions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 23 (14), 14221-14230 (2016).

- Quinn, G. A., Maloy, A. P., McClean, S., Carney, B., Slater, J. W. Lipopeptide biosurfactants from Paenibacillus polymyxa inhibit single and mixed species biofilms. Biofouling. 28 (10), 1151-1166 (2012).

- Gudiña, E. J., et al. Novel bioemulsifier produced by a Paenibacillus strain isolated from crude oil. Microbial Cell Factories. 14 (1), 1-11 (2015).

- Pradhan, A. K., Pradhan, N., Sukla, L. B., Panda, P. K., Mishra, B. K. Inhibition of pathogenic bacterial biofilm by biosurfactant produced by Lysinibacillus fusiformis S9. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering. 37 (2), 139-149 (2014).

- Manchola, L., Dussán, J. Lysinibacillus sphaericus and Geobacillus sp biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons and biosurfactant production. Remediation Journal. 25 (1), 85-100 (2014).

- Bhardwaj, G., Cameotra, S. S., Chopra, H. K. Biosurfactant from Lysinibacillus chungkukjangi from rice bran oil sludge and potential applications. Journal of Surfactants and Detergents. 19 (5), 957-965 (2016).

- Gaur, V. K., et al. Rhamnolipid from a Lysinibacillus sphaericus strain IITR51 and its potential application for dissolution of hydrophobic pesticides. Bioresource Technology. 272, 19-25 (2019).

- Habib, S., et al. Production of lipopeptide biosurfactant by a hydrocarbon-degrading Antarctic Rhodococcus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (17), 6138 (2020).

- Shao, P., Ma, H., Zhu, J., Qiu, Q. Impact of ionic strength on physicochemical stability of o/w emulsions stabilized by Ulva fasciata polysaccharide. Food Hydrocolloids. 69, 202-209 (2017).

- . Overview of DLVO theory Available from: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:148595 (2014)

- Kazemzadeh, Y., Ismail, I., Rezvani, H., Sharifi, M., Riazi, M. Experimental investigation of stability of water in oil emulsions at reservoir conditions: Effect of ion type, ion concentration, and system pressure. Fuel. 243, 15-27 (2019).

- Chong, H., Li, Q. Microbial production of rhamnolipids: opportunities, challenges and strategies. Microbial Cell Factories. 16 (1), 1-12 (2017).

- Zeng, G., et al. Co-degradation with glucose of four surfactants, CTAB, Triton X-100, SDS and Rhamnolipid, in liquid culture media and compost matrix. Biodegradation. 18 (3), 303-310 (2007).

- Liu, G., et al. Advances in applications of rhamnolipids biosurfactant in environmental remediation: a review. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 115 (4), 796-814 (2018).

- John, W. C., Ogbonna, I. O., Gberikon, G. M., Iheukwumere, C. C. Evaluation of biosurfactant production potential of Lysinibacillus fusiformis MK559526 isolated from automobile-mechanic-workshop soil. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 52 (2), 663-674 (2021).

- Naing, K. W., et al. Isolation and characterization of an antimicrobial lipopeptide produced by Paenibacillus ehimensis MA2012. Journal of Basic Microbiology. 55 (7), 857-868 (2015).

- Wittgens, A., et al. Novel insights into biosynthesis and uptake of rhamnolipids and their precursors. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 101 (7), 2865-2878 (2017).

- Rahman, K., Rahman, T. J., McClean, S., Marchant, R., Banat, I. M. Rhamnolipid biosurfactant production by strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using low-cost raw materials. Biotechnology Progress. 18 (6), 1277-1281 (2002).

- Bahia, F. M., et al. Rhamnolipids production from sucrose by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Scientific Reports. 8 (1), 1-10 (2018).

- Kim, C. H., et al. Desorption and solubilization of anthracene by a rhamnolipid biosurfactant from Rhodococcus fascians. Water Environment Research. 91 (8), 739-747 (2019).

- Nalini, S., Parthasarathi, R. Optimization of rhamnolipid biosurfactant production from Serratia rubidaea SNAU02 under solid-state fermentation and its biocontrol efficacy against Fusarium wilt of eggplant. Annals of Agrarian Science. 16 (2), 108-115 (2018).

- Wang, Q., et al. Engineering bacteria for production of rhamnolipid as an agent for enhanced oil recovery. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 98 (4), 842-853 (2007).

- Câmara, J., Sousa, M., Neto, E. B., Oliveira, M. Application of rhamnolipid biosurfactant produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in microbial-enhanced oil recovery (MEOR). Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology. 9 (3), 2333-2341 (2019).

- Amani, H., Mehrnia, M. R., Sarrafzadeh, M. H., Haghighi, M., Soudi, M. R. Scale up and application of biosurfactant from Bacillus subtilis in enhanced oil recovery. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 162 (2), 510-523 (2010).

- Gudiña, E. J., et al. Bioconversion of agro-industrial by-products in rhamnolipids toward applications in enhanced oil recovery and bioremediation. Bioresource Technology. 177, 87-93 (2015).

- Sun, G., Hu, J., Wang, Z., Li, X., Wang, W. Dynamic investigation of microbial activity in microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR). Petroleum Science and Technology. 36 (16), 1265-1271 (2018).

- Jha, S. S., Joshi, S. J., SJ, G. Lipopeptide production by Bacillus subtilis R1 and its possible applications. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 47 (4), 955-964 (2016).

- Darvishi, P., Ayatollahi, S., Mowla, D., Niazi, A. Biosurfactant production under extreme environmental conditions by an efficient microbial consortium, ERCPPI-2. Colloids and Surfaces. B, Biointerfaces. 84 (2), 292-300 (2011).

- Al-Wahaibi, Y., et al. Biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis B30 and its application in enhancing oil recovery. Colloids and Surfaces. B, Biointerfaces. 114, 324-333 (2014).

- Moutinho, L. F., Moura, F. R., Silvestre, R. C., Romão-Dumaresq, A. S. Microbial biosurfactants: A broad analysis of properties, applications, biosynthesis, and techno-economical assessment of rhamnolipid production. Biotechnology Progress. 37 (2), 3093 (2021).

- Youssef, N., Simpson, D. R., McInerney, M. J., Duncan, K. E. In-situ lipopeptide biosurfactant production by Bacillus strains correlates with improved oil recovery in two oil wells approaching their economic limit of production. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 81, 127-132 (2013).

- Ruckenstein, E., Nagarajan, R. Critical micelle concentration and the transition point for micellar size distribution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 85 (20), 3010-3014 (1981).

- de Araujo, L. L., et al. Microbial enhanced oil recovery using a biosurfactant produced by Bacillus safensis isolated from mangrove microbiota-Part I biosurfactant characterization and oil displacement test. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering. 180, 950-957 (2019).

- Banat, I. M., De Rienzo, M. A. D., Quinn, G. A. Microbial biofilms: biosurfactants as antibiofilm agents. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 98 (24), 9915-9929 (2014).

- Klosowska-Chomiczewska, I., Medrzycka, K., Karpenko, E. Biosurfactants-biodegradability, toxicity, efficiency in comparison with synthetic surfactants. Research and Application of New Technologies in Wastewater Treatment and Municipal Solid Waste Disposal in Ukraine, Sweden, and Poland. 17, 141-149 (2013).

- Fernandes, P. A. V., et al. Antimicrobial activity of surfactants produced by Bacillus subtilis R14 against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 38 (4), 704-709 (2007).

- Santos, D. K. F., Rufino, R. D., Luna, J. M., Santos, V. A., Sarubbo, L. A. Biosurfactants: multifunctional biomolecules of the 21st century. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (3), 401 (2016).