Das Split-Brain

English

Compartir

Descripción

Quelle: Laboratorien der Jonas T. Kaplan und der Sarah I. Gimbel-Universität von Südkalifornien

Die Studie wie Schädigung des Gehirns beeinflussen kognitive Funktion wurde historisch eines der wichtigsten Werkzeuge für kognitive Neurowissenschaft. Während das Gehirn eines der am besten geschützten Teile des Körpers ist, gibt es viele Veranstaltungen, die das Funktionieren des Gehirns beeinflussen können. Vaskuläre Probleme, Tumoren, degenerativen Erkrankungen, Infektionen, stumpfe Kraft Traumata und Neurochirurgie sind nur einige der zugrunde liegenden Ursachen der Schädigung des Gehirns, die unterschiedliche Muster von Gewebeschäden führen kann, die Hirnfunktion auf unterschiedliche Weise beeinflussen.

Die Geschichte der Neuropsychologie zeichnet sich durch mehrere bekannte Fälle, die Fortschritte im Verständnis des Gehirns geführt. Zum Beispiel in 1861 Paul Broca beobachtet wie Schäden an der linken frontalen Lappen Aphasie, eine erworbene Sprachstörung führte. Als weiteres Beispiel hat viel über das Gedächtnis gelernt von Patienten mit Amnesie, wie den berühmten Fall von Henry Molaison, bekannt seit vielen Jahren in der Neuropsychologie Literatur als “H.M,” deren Temporallappen-Operation zu einem tiefen Defizit führte bei der Bildung von bestimmten Arten von neuen Erinnerungen.

Während der Beobachtung und Prüfung von Patienten mit fokalen Hirnschädigung hat Neurowissenschaften mit Einblick in die Funktionsweise des Gehirns, große Sorgfalt bei der Gestaltung von Prüfungen getroffen werden muss, um den besonderen Charakter des Defizits zu offenbaren. Auch, weil das Gehirn ein komplexes Netzwerk von miteinander verbundenen Neuronen ist, kann Schäden an einer Hirnregion funktionieren beeinträchtigen in Regionen fernab von den Schaden. Um zu demonstrieren wie Hirnschäden Verbindungen zwischen den einzelnen Hirnregionen beeinflussen kann, untersucht dieses Video den Fall des so genannten Split-Gehirns.

Corpus Callosum ist ein großes Bündel von Fasern, die die linken und rechten Hemisphären des Gehirns verbindet. Es ist eines der größten weißen Substanz Tracts im Gehirn und kann leicht auf einen sagittalen Blick auf der Mittellinie des Gehirns erkannt werden. In den 1960er Jahren entdeckt Neurochirurgen, dass Schneiden Corpus Callosum eine erfolgreiche Behandlung für bestimmte Arten von Epilepsie, könnte dem unkontrollierbaren neuronalen Aktivität Verbreitung durch das Gehirn beteiligt. Menschen, die die Split-Brain-Operation unterzogen hatten ihre beiden Gehirnhälften operativ getrennt, derart, dass die linken und rechten Gehirnhälfte nicht mehr kommunizieren konnten. Diese Bedingung erlaubt Experimentatoren, die Funktionen der linken und rechten Hemisphäre Sonde unabhängig, erfahren Sie über die relative Fähigkeit und über die Art der Kommunikation zwischen ihnen.

Dieses Video veranschaulicht, wie einen Split-Brain-Patienten, die Unterschiede zwischen den beiden Hemisphären des Gehirns zu offenbaren und zu sehen, einige dramatische Folgen eine solche Trennung zu testen. Die Originalversionen dieser Experimente wurden von Michael Gazzaniga und Kollegen1, 2 entwickelt und später von anderen ausgeführt wurden; 3 die Version hier vorgestellt enthält den letzten Modernisierungen der Methodik.

Procedimiento

Resultados

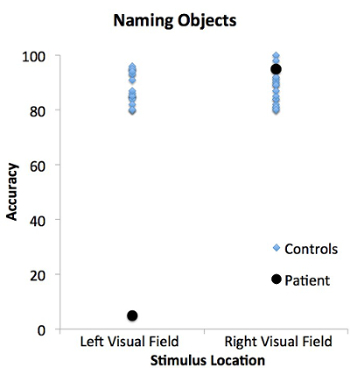

Typically, callosotomy patients exhibit an anomia for objects presented in the left visual half-field. Anomia is the inability to name objects. Objects presented to the right visual field, however, are named with high accuracy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Patient and control performance in the naming objects task for stimuli presented in the left and right visual fields. The patient (black circles) is not able to verbally name objects presented in the left visual field, but is able to name objects in the right visual field. In contrast, the control population (blue diamonds) can name objects presented in both the left and right visual fields.

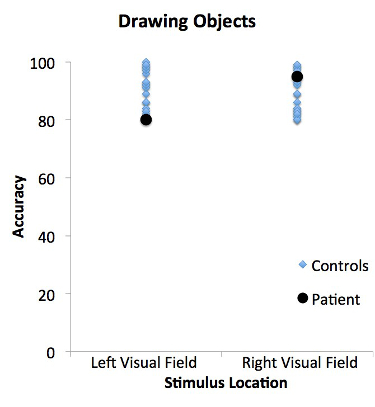

Some patients may be able to successfully draw objects presented to the left visual field, even though they cannot verbally name them (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Patient and control performance in the drawing objects task for stimuli presented in the left and right visual fields. The patient (black circles) and control population (blue diamonds) are able to draw objects presented in both the left and right visual fields. The patient's performance does not differ from matched controls.

In this case, the patient usually says they haven't seen anything. This is because the left hemisphere, which is controlling speech, has not seen the visual image. However, the right hemisphere, which has seen the object, can recognize it but is unable to generate speech. Since the right hemisphere is largely in control of the left hand, the patient is able to draw the object with the left hand. This result demonstrates a dissociation between the ability to recognize an object and the ability to verbally name an object.

The control population, with intact corpora callosa, can both name and draw objects presented in the left or right visual fields. This is because information can freely pass from one hemisphere to the other, allowing for the sharing of information between the brain regions.

Applications and Summary

The case of the split-brain patient reveals the relative specialization of the two cerebral hemispheres. Many of these specializations can also be demonstrated in healthy people with intact commissures using similar techniques. For example, people tend to recognize words faster when they are presented briefly in the right visual field compared to when they are presented in the left visual field. This experiment also shows that even when two brain regions are healthy, damage to the connections between different regions can affect behavior.

However, it is important to remember that while testing the split brain demonstrates the differences between the two cerebral hemispheres, in the intact brain, the two hemispheres are continually interacting with each other and working in concert. To isolate a stimulus to one visual field requires specialized equipment that can present stimuli very briefly and away from central fixation. Since central vision is processed by both hemispheres, and the eyes typically scan an environment, this is not a situation that is likely to be encountered in everyday life.

Referencias

- Gazzaniga, M. S., Bogen, J. E., & Sperry, R. W. (1962). Some functional effects of sectioning the cerebral commissures in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 48, 1765-1769.

- Gazzaniga, M. S., Bogen, J. E., & Sperry, R. W. (1965). Observations on visual perception after disconnexion of the cerebral hemispheres in man. Brain, 88(2), 221-236.

- Zaidel, E., Zaidel, D., & Bogen, J. E. (1990). Testing the commussurotomy patient. In A. Boulton, G. Baker, & M. Hiscock (Eds.), Neuromethods (pp. 147-201). Clifton, NJ: Humana Press.

Transcripción

Neuropsychologists study “split-brain” patients to probe the unique functions of the left and right brain hemispheres—in other words, to study lateralization—and to also investigate the nature of communication between these regions.

Primarily speaking, information from one side of the body is processed within the opposite half of the brain. In addition, each hemisphere contralaterally directs body movements.

These areas also have different cognitive strengths: the left side is typically associated with the control of language and speech, whereas the right plays a large role in processing visuospatial information—like judging the spatial arrangements of dials on a machine.

Normally, collections of neurons’ axons—referred to as nerve fiber bundles—transfer information between these hemispheres. One of the largest of such tracts is the corpus callosum.

However, this inter-hemispheric communication is interrupted in split-brain patients, whose corpora callosa have been surgically severed—a treatment sometimes used to reduce the uncontrollable neural activity characteristic of epilepsy from spreading throughout the entire brain.

Using modernizations of psychologist Michael Gazzaniga’s techniques, this video demonstrates how to test split-brain patients and assess their cognitive abilities—specifically speech production—and illustrates data collection and analysis methods.

In this experiment, patients are shown images of everyday objects and asked to verbalize the name of each item.

To achieve lateralization, patients are instructed to focus on a cross symbol in the center of a computer screen, and told to remain fixated on this shape for the duration of the experiment. Here, the cross serves as a reference point next to which visual stimuli can be shown on either the right or left.

If an image is presented on the right of the screen, it falls into the right visual field—which, perhaps counterintuitively, is processed by the left portions of both eyes. These regions then project the observed image to the left hemisphere of the brain, where it is identified.

Thus, functions of the left brain hemisphere can be assessed by showing images in the right visual field.

Similarly, a stimulus presented to the left of the cross onscreen—in the left visual field—can be used to evaluate the roles of the right hemisphere.

During the naming objects task, a total of fifty drawings, like that of a chicken, appear one at a time on a random side of the monitor—either the right or left.

Pictures are presented for less than 150 ms. As this is not enough time for a patient to move their eyes to reposition the image, it ensures that only the brain hemisphere being tested “sees” the stimulus.

After the image disappears, the patient must identify it aloud, which serves as a measure of the lateralization of verbal linguistic capability.

Here, the dependent variable is the percentage of images shown in the left and right visual fields that the patient is able to name—in other words, the accuracy of verbal identification.

Based on the previous work of Gazzaniga and others, it is expected that patients will be able to name images presented in the right visual field with high accuracy, as this information is seen by the left hemisphere—the region capable of controlling speech.

However, patients will be unable to verbally identify pictures shown in the left visual field, as this information is handled by the right brain hemisphere, which is incapable of generating language and—in split-brain patients—cannot communicate with the speech-capable left side.

If the image can’t be named—referred to as anomia—a drawing task is performed, which serves as a non-linguistic measure of stimulus knowledge.

Here, patients must create a picture of the image they were shown using the hand on the ipsilateral or same side as the tested visual field. Thus, if patients can’t verbally identify an object presented on the left of the screen, they should draw it with their left hand.

In this instance, the dependent variable is the percentage of images shown in the left and right visual fields that are accurately drawn.

It is expected that patients unable to name pictures shown on the left of the monitor will still be able to draw them—using their left hand—with high accuracy.

This is due to the fact that the right hemisphere—which controls the left arm and hand—also processes information from the left visual field. Thus, no communication is needed between the hemispheres to complete this task.

Prior to beginning the experiment, review patients’ MRI data to determine which nerve fiber bundles they are lacking. For the purpose of this demonstration, a patient in whom the entire corpus callosum has been severed is tested, and their data will be compared to those collected from control participants.

Greet the patient when they arrive, and inform them of the research procedures. In addition, assure that they have signed all appropriate consent forms.

Then, proceed to place their chin comfortably in a chinrest so that their eyes are positioned approximately 22 in. from the screen.

With the small cross displayed in the center of the screen, emphasize to the patient that they must remain fixated on this symbol, even as images flash to the left or right of it.

Proceed by showing them 50 images, each of which are presented for 150 ms, in a random order, and evenly divided between sides. After every presentation, instruct the patient to identify the object out loud: “Apple”. Record all of their responses.

If the patient cannot name the visual stimulus, ask them to draw it with the hand on the same side as the visual field in which the picture was shown. This constitutes the drawing objects task.

Make sure that the patient does not look at their hand as they are drawing, in order to maintain the initial isolation of the stimulus to one brain hemisphere.

To confirm that the patient knows the name of the stimulus when it is simultaneously presented to both fields of view, have them look down at their completed drawing and verbally identify the object it represents: “Broom”. Again, record all of the patient’s responses.

To analyze the data, first calculate the percentage of correct verbal responses across patients for stimuli presented to the left and right visual fields.

Proceed by separately compiling the percentage of correct verbal response scores for each control participant’s left and right locations.

To identify any deficits in patient behavior, compare control and patient data using a repeated-measures analysis of variance test. Repeat the analysis for all data collected from the drawing test.

Notice that while patients are typically unable to name stimuli presented to the left visual field, they can draw them—with their left hand—with a high degree of accuracy. This demonstrates a dissociation between a patient’s ability to recognize and verbally name an object.

Now that you know how to test the functions of the left and right hemispheres of split-brain patients with visual stimuli, let’s see how researchers explore and apply lateralization in other contexts.

You’ve learned that surgical separation of the two hemispheres is often used to treat patients with epilepsy, which is characterized by seizures.

As a result, many neuroscientists are looking at whether the timing of this disconnection—whether the corpus callosum is severed during childhood or adulthood—has any affect on a patient’s cognitive functions.

Importantly, such work has demonstrated that compared to adults, children experience fewer—or less severe—cognitive effects following the disconnection of the brain hemispheres, suggesting that young brains demonstrate a great degree of plasticity.

Up until now, we’ve focused on the corpus callosum as the major connection between the left and right hemispheres.

However, other nerve fiber bundles allow for communication between the sides of the brain. Among them is the anterior commissure, which has been implicated in the transfer of sensory information, like that pertaining to sight or smell.

Thus, some researchers are looking at how the disconnection of one or more of these bundles—with or without severance of the corpus callosum—affects patient behavior.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on testing split-brain patients using visual stimuli. By now, you should understand how to present images to the two visual fields, and collect and interpret data relating to the abilities of the left and right brain hemispheres. You should also know how data from split-brain patients is being used to develop better treatments for epilepsy, and understand the roles of different nerve fiber bundles in the brain.

Thanks for watching!