药物与DNA相互作用的细胞全基因组映射与COSMIC(小分子交联,染色质隔离)

Summary

识别基因组靶向分子的直接目标仍然是一个重大的挑战。要了解DNA结合分子如何参与基因组,我们开发了依靠小分子交联,染色质隔离的方法(COSMIC)。

Abstract

基因组是一些最有效的化学治疗剂的目标,但大多数这些药物缺乏DNA序列特异性,从而导致剂量限制性毒性和许多不良副作用。靶向序列特异性小分子的基因组中可使得分子具有增加的治疗指数和更少的脱靶效应。ñ-methylpyrrole / N甲基咪唑聚酰胺是分子,可以进行合理设计为靶向精致精度特定的DNA序列。不像最自然的转录因子,聚酰胺可以绑定到甲基化和chromatinized DNA无亲和力的损失。聚酰胺的序列特异性已被广泛研究在体外用同源站点识别(CSI),并用传统的生化和生物物理方法,但聚酰胺的细胞结合的基因组的目标的研究仍然难以捉摸。在这里,我们报告的方法,小分子交联伊索拉德染色质(COSMIC),标识在整个基因组聚酰胺结合位点。 COSMIC类似于染色质免疫沉淀,但不同之在两个重要方面:(1)一个光交联剂被用来使选择性的,在时间上控制捕获的聚酰胺结合事件,和(2)的生物素亲和手柄用于纯化聚酰胺半变性条件下-DNA偶联物降低的DNA即非共价结合。宇宙是可用于揭示聚酰胺和其他基因组靶向化学治疗剂的全基因组结合事件一般策略。

Introduction

的信息,使在人体每个小区被编码在DNA中。有选择地利用这些信息用于调控细胞的命运。转录因子(TF)是结合特定的DNA序列,以表达在基因组中的基因的特定子集蛋白和转录因子的故障是与疾病各种各样的发作,包括发育缺陷,癌症和糖尿病1,2我们一直有兴趣开发分子,可以选择性地结合到基因组中并调节基因调控网络。

聚酰胺由 N个-methylpyrrole的和 N-甲基咪唑能合理设计的分子,可以靶DNA与特异性和亲和力,其竞争对手天然转录因子。3-6这些分子结合在DNA的小沟中的特异性序列。4,5,7 -11聚酰胺已采用两个再加压和激活的特定克的表达埃内斯。4,12-19他们也有有趣的抗病毒20-24和抗癌12,13,25-30性能。聚酰胺之一有吸引力的特点是它们的访问被甲基31,32和缠组蛋白9,10,33 DNA序列的能力。

为了测量DNA结合分子的全面结合特异性,我们实验室建立的同源站点标识符(CSI)的方法。34-39的基于体外的特异性(genomescapes)结合位点的预测的发生可以在基因组上被显示,因为在体外结合强度成正比缔合常数(K a)的 34,35,37,这些genomescapes洞察在整个基因组聚酰胺占用,但测量聚酰胺在活细胞中的结合一直是个难题。 DNA被紧紧包装在细胞核中,它可能会影响结合位点的可接近性。在一个这些chromatinized DNA序列聚酰胺ccessibility仍是一个谜。

最近,许多方法来研究已经出现小分子和核酸之间的相互作用。40-48的化学亲和捕获和大规模并行DNA测序(CHEM-SEQ)是一种这样的技术。的Chem-以次使用甲醛交联的小分子到感兴趣的基因组靶和小分子的感兴趣的生物素化的衍生物捕获配体-靶相互作用。48,49

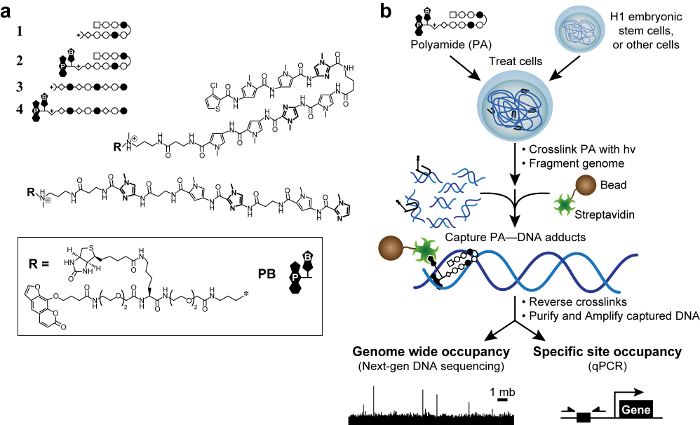

甲醛的交联导致了可以产生假阳性的间接相互作用。50我们开发了一种新方法,小分子的交联以分离染色质(COSMIC),51与光交联剂,以消除这些所谓的“幻影”的峰。50首先,我们设计并合成聚酰胺的三官能的衍生物。这些分子含有一个DNA结合聚合酶yamide,光交联剂(补骨脂素),和亲和手柄(生物素, 图1)。用三官能聚酰胺,我们可以共价捕获与365nm的紫外线照射下,一个波长不损害DNA或诱导非补骨脂类交联剂聚酰胺-DNA相互作用。51接下来,我们片段的基因组中,净化捕获的DNA在严格的,半-denaturing条件以降低的DNA即非共价结合。因此,我们认为COSMIC作为与化学 – 以次的方法,但用的DNA的更直接读出定位。重要的是,弱(K 10 3 -10 4 M -1)补骨脂用于DNA的亲和力没有可检测的影响的聚酰胺特 异性。51,52富集的DNA片段可以通过定量聚合酶链反应51待分析(COSMIC-qPCR的)或者通过新一代测序53(COSMIC-SEQ)。这些数据使能配体的一个不带偏见,全基因组指导下设计,跨充当与他们所希望的基因位点,并尽量减少脱靶效应。

图1.生物活性聚酰胺和宇宙方案 。 (一)夏萍聚酰胺1 – 2靶DNA序列5'-WACGTW-3“。线性聚酰胺3 – 4靶 5'- AAGAAGAAG-3'。 N-甲基咪唑的环以粗体显示的清晰度。开放和充满圆圈表示 N -methylpyrrole 和 N甲基咪唑,分别。方块代表3氯噻吩和菱形代表β丙氨酸。补骨脂素和生物素是由P和B,分别表示。 (二)COSMIC计划。细胞用聚酰胺的三官能的衍生物。用365nm的UV照射交联后,将细胞是升ysed和基因组DNA被剪切。链亲和素包被的磁珠加入到捕获聚酰胺的DNA加合物。该DNA被释放,并可以通过定量PCR(定量PCR)或下一代测序(NGS)进行分析。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

One of the primary challenges with conventional ChIP is the identification of suitable antibodies. ChIP depends heavily upon the quality of the antibody, and most commercial antibodies are unacceptable for ChIP. In fact, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) consortium found only 20% of commercial antibodies to be suitable for ChIP assays.50 With COSMIC, antibodies are replaced by streptavidin. Because polyamides are functionalized with biotin, streptavidin is used in place of an antibody to capture polyam…

Divulgations

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Ansari lab and Prof. Parameswaran Ramanathan for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants CA133508 and HL099773, the H. I. Romnes faculty fellowship, and the W. M. Keck Medical Research Award to A.Z.A. G.S.E. was supported by a Peterson Fellowship from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biosciences Training Grant NIH T32 GM07215. A.E. was supported by the Morgridge Graduate Fellowship and the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center Fellowship, and D.B. was supported by the NSEC grant from NSF.

Materials

| Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) | any source | ||

| Benzamidine | any source | ||

| Pepstatin | any source | ||

| Proteinase K | any source | ||

| Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 | Life Technologies | 65001 | |

| PBS, pH 7.4 | Life Technologies | 10010-023 | Other sources can be used |

| StemPro® Accutase® Cell Dissociation Reagent | Life Technologies | A1110501 | |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | 28104 | We have tried other manufacturers of DNA columns with success. |

| TruSeq ChIP Sample Prep Kit | Illumina | IP-202-1012 | This Kit can be used to prepare COSMIC DNA for next-generation sequencing |

| Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix | BD Biosciences | 356231 | Used to coat plates in order to grow H1 ESCs |

| pH paper | any source | ||

| amber microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| pyrex filter | any source | Pyrex baking dishes are suitable | |

| qPCR master mix | any source | ||

| RNase | any source | ||

| HCl (6 N) | any source | ||

| 10-cm tissue culture dishes | any source | ||

| Serological pipettes | any source | ||

| Pasteur pipettes | any source | ||

| Pipette tips | any source | ||

| 15-mL conical tubes | any source | ||

| centrifuge | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge | any source | ||

| nutator | any source | ||

| Magnetic separation rack | any source | ||

| UV source | CalSun | B001BH0A1A | Other UV sources can be used, but crosslinking time must be optimized empirically |

| Misonix Sonicator | Qsonica | S4000 with 431C1 cup horn | Other sonicators can be used, but sonication conditions must be optimized empirically |

| Humidified CO2 incubator | any source | ||

| Biological safety cabinet with vacuum outlet | any source |

References

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional Regulation and Its Misregulation in Disease. Cell. 152, 1237-1251 (2013).

- Vaquerizas, J. M., Kummerfeld, S. K., Teichmann, S. A., Luscombe, N. M. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 10, 252-263 (2009).

- Meier, J. L., Yu, A. S., Korf, I., Segal, D. J., Dervan, P. B. Guiding the Design of Synthetic DNA-Binding Molecules with Massively Parallel Sequencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17814-17822 (2012).

- Dervan, P. B. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 2215-2235 (2001).

- Wemmer, D. E., Dervan, P. B. Targeting the minor groove of DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 355-361 (1997).

- Eguchi, A., Lee, G. O., Wan, F., Erwin, G. S., Ansari, A. Z. Controlling gene networks and cell fate with precision-targeted DNA-binding proteins and small-molecule-based genome readers. Biochem. J. 462, 397-413 (2014).

- Mrksich, M., et al. Antiparallel side-by-side dimeric motif for sequence-specific recognition in the minor groove of DNA by the designed peptide 1-methylimidazole-2-carboxamide netropsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 89, 7586-7590 (1992).

- Edayathumangalam, R. S., Weyermann, P., Gottesfeld, J. M., Dervan, P. B., Luger, K. Molecular recognition of the nucleosomal “supergroove”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 6864-6869 (2004).

- Suto, R. K., et al. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 371-380 (2003).

- Gottesfeld, J. M., et al. Sequence-specific Recognition of DNA in the Nucleosome by Pyrrole-Imidazole Polyamides. J. Mol. Biol. 309, 615-629 (2001).

- Chenoweth, D. M., Dervan, P. B. Structural Basis for Cyclic Py-Im Polyamide Allosteric Inhibition of Nuclear Receptor Binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14521-14529 (2010).

- Raskatov, J. A., et al. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription using programmable DNA minor groove binders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1023-1028 (2012).

- Yang, F., et al. Antitumor activity of a pyrrole-imidazole polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1863-1868 (2013).

- Mapp, A. K., Ansari, A. Z., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Activation of gene expression by small molecule transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3930-3935 (2000).

- Ansari, A. Z., Mapp, A. K., Nguyen, D. H., Dervan, P. B., Ptashne, M. Towards a minimal motif for artificial transcriptional activators. Chem. Biol. 8, 583-592 (2001).

- Arora, P. S., Ansari, A. Z., Best, T. P., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Design of artificial transcriptional activators with rigid poly-L-proline linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13067-13071 (2002).

- Nickols, N. G., Jacobs, C. S., Farkas, M. E., Dervan, P. B. Modulating Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription by Disrupting the HIF-1–DNA Interface. ACS Chemical Biology. 2, 561-571 (2007).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. A synthetic small molecule for rapid induction of multiple pluripotency genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2, 544 (2012).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. Synthetic Small Molecules for Epigenetic Activation of Pluripotency Genes in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts. Chem Bio Chem. 12, 2822-2828 (2011).

- He, G., et al. Binding studies of a large antiviral polyamide to a natural HPV sequence. Biochimie. 102, 83-91 (2014).

- Edwards, T. G., Vidmar, T. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. DNA Damage Repair Genes Controlling Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Episome Levels under Conditions of Stability and Extreme Instability. PLoS ONE. 8, e75406 (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., Helmus, M. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. HPV Episome Stability is Reduced by Aphidicolin and Controlled by DNA Damage Response Pathways. Journal of Virology. , (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., et al. HPV episome levels are potently decreased by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Antiviral Res. 91, 177-186 (2011).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription in human cells by synthetic DNA-binding ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12890-12895 (1998).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Arresting Cancer Proliferation by Small-Molecule Gene Regulation. Chem. Biol. 11, 1583-1594 (2004).

- Nickols, N. G., et al. Activity of a Py–Im Polyamide Targeted to the Estrogen Response Element. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 12, 675-684 (2013).

- Raskatov, J. A., Puckett, J. W., Dervan, P. B. A C-14 labeled Py–Im polyamide localizes to a subcutaneous prostate cancer tumor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 4371-4375 (2014).

- Jespersen, C., et al. Chromatin structure determines accessibility of a hairpin polyamide–chlorambucil conjugate at histone H4 genes in pancreatic cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 4068-4071 (2012).

- Chou, C. J., et al. Small molecules targeting histone H4 as potential therapeutics for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 7, 769-778 (2008).

- Nickols, N. G., Dervan, P. B. Suppression of androgen receptor-mediated gene expression by a sequence-specific DNA-binding polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10418-10423 (2007).

- Minoshima, M., Bando, T., Sasaki, S., Fujimoto, J., Sugiyama, H. Pyrrole-imidazole hairpin polyamides with high affinity at 5CGCG3 DNA sequence; influence of cytosine methylation on binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2889-2894 (2008).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Fabrication of duplex DNA microarrays incorporating methyl-5-cytosine. Lab on a Chip. 12, 376-380 (2012).

- Dudouet, B., et al. Accessibility of nuclear chromatin by DNA binding polyamides. Chem. Biol. 10, 859-867 (2003).

- Carlson, C. D., et al. Specificity landscapes of DNA binding molecules elucidate biological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4544-4549 (2010).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Defining the sequence-recognition profile of DNA-binding molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 867-872 (2006).

- Tietjen, J. R., Donato, L. J., Bhimisaria, D., Ansari, A. Z., Voigt, C. Chapter One – Sequence-Specificity and Energy Landscapes of DNA-Binding Molecules. Methods Enzymol. 497, 3-30 (2011).

- Puckett, J. W., et al. Quantitative microarray profiling of DNA-binding molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12310-12319 (2007).

- Keles, S., Warren, C. L., Carlson, C. D., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-Tree: a regression tree approach for modeling binding properties of DNA-binding molecules based on cognate site identification (CSI) data. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3171-3184 (2008).

- Hauschild, K. E., Stover, J. S., Boger, D. L., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-FID: High throughput label-free detection of DNA binding molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 3779-3782 (2009).

- Lee, M., Roldan, M. C., Haskell, M. K., McAdam, S. R., Hartley, J. A. . In vitro Photoinduced Cytotoxicity and DNA Binding Properties of Psoralen and Coumarin Conjugates of Netropsin Analogs: DNA Sequence-Directed Alkylation and Cross-Link. 37, 1208-1213 (1994).

- Wurtz, N. R., Dervan, P. B. Sequence specific alkylation of DNA by hairpin pyrrole–imidazole polyamide conjugates. Chem. Biol. 7, 153-161 (2000).

- Tung, S. -. Y., Hong, J. -. Y., Walz, T., Moazed, D., Liou, G. -. G. Chromatin affinity-precipitation using a small metabolic molecule: its application to analysis of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 641-650 (2012).

- Rodriguez, R., Miller, K. M. Unravelling the genomic targets of small molecules using high-throughput sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 15, 783-796 (2014).

- Guan, L., Disney, M. D. Covalent Small-Molecule–RNA Complex Formation Enables Cellular Profiling of Small-Molecule–RNA Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10010-10013 (2013).

- White, J. D., et al. Picazoplatin, an Azide-Containing Platinum(II) Derivative for Target Analysis by Click Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11680-11683 (2013).

- Rodriguez, R., et al. Small-molecule–induced DNA damage identifies alternative DNA structures in human genes. Nat Chem Biol. 8, 301-310 (2012).

- Bando, T., Sugiyama, H. Synthesis and Biological Properties of Sequence-Specific DNA-Alkylating Pyrrole−Imidazole Polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 935-944 (2006).

- Anders, L., et al. Genome-wide localization of small molecules. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 92-96 (2014).

- Jin, C., et al. Chem-seq permits identification of genomic targets of drugs against androgen receptor regulation selected by functional phenotypic screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9235-9240 (2014).

- Landt, S. G., et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Research. 22, 1813-1831 (2012).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Eguchi, A., Ansari, A. Z. Mapping Polyamide–DNA Interactions in Human Cells Reveals a New Design Strategy for Effective Targeting of Genomic Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10124-10128 (2014).

- Hyde, J. E., Hearst, J. E. Binding of psoralen derivatives to DNA and chromatin: influence of the ionic environment on dark binding and photoreactivity. Biochimie. 17, 1251-1257 (1978).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Rodríguez-Martínez, J. A., Grieshop, M. P., Ansari, A. Z. Genome-wide localization of polyamide-based genome readers reveals sequence-based binding to repressive heterochromatin. In preparation. , (2015).

- Chen, G., et al. Chemically defined conditions for human iPSC derivation and culture. Nat Meth. 8, 424-429 (2011).

- Deliard, S., Zhao, J., Xia, Q., Grant, S. F. A. Generation of High Quality Chromatin Immunoprecipitation DNA Template for High-throughput Sequencing (ChIP-seq). J Vis Exp. (74), e50286 (2013).

- Shi, Y. B., Spielmann, H. P., Hearst, J. E. Base-catalyzed reversal of a psoralen-DNA cross-link. Biochimie. 27, 5174-5178 (1988).

- Kumaresan, K. R., Hang, B., Lambert, M. W. Human Endonucleolytic Incision of DNA 3′ and 5′ to a Site-directed Psoralen Monoadduct and Interstrand. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30709-30716 (1995).

- Cimino, G. D., Shi, Y. B., Hearst, J. E. Wavelength dependence for the photoreversal of a psoralen-DNA crosslink. Biochimie. 25, 3013-3020 (1986).

- Heinz, S., et al. Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Mol. Cell. 38, 576-589 (2010).

- Zhang, Y., et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

- Kharchenko, P. V., Tolstorukov, M. Y., Park, P. J. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotech. 26, 1351-1359 (2008).

- Diamandis, E. P., Christopoulos, T. K. The biotin-(strept)avidin system: principles and applications in biotechnology. Clin. Chem. 37, 625-636 (1991).

- Martinson, H. G., True, R. J. On the mechanism of nucleosome unfolding. Biochimie. 18, 1089-1094 (1979).

- Gloss, L. M., Placek, B. J. The Effect of Salts on the Stability of the H2A−H2B Histone Dimer. Biochimie. 41, 14951-14959 (2002).

- Jackson, V. Formaldehyde Cross-Linking for Studying Nucleosomal Dynamics. Methods. 17, 125-139 (1999).

- Kasinathan, S., Orsi, G. A., Zentner, G. E., Ahmad, K., Henikoff, S. High-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites on native chromatin. Nat Meth. 11, 203-209 (2014).

- Teytelman, L., Thurtle, D. M., Rine, J., van Oudenaarden, A. Highly expressed loci are vulnerable to misleading ChIP localization of multiple unrelated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18602-18607 (2013).

- . Phantompeakqualtools home page Available from: https://www.encodeproject.org/software/phantompeakqualtools/ (2010)

- Wang, D., Lippard, S. J. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 4, 307-320 (2005).

- Hurley, L. H. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2, 188-200 (2002).