Genoombrede kartering van Drug-DNA interacties in cellen met kosmische (Crosslinking van kleine moleculen te isoleren chromatine)

Summary

Het identificeren van de directe doelstellingen van genoom-gerichte moleculen blijft een grote uitdaging. Om te begrijpen hoe DNA-bindende moleculen die aangrijpen op de genoom, ontwikkelden we een methode die is gebaseerd op de verknoping van kleine moleculen aan chromatine isoleren (COSMIC).

Abstract

Het genoom is het doelwit van een aantal van de meest effectieve chemotherapeutica, maar de meeste van deze geneesmiddelen missen DNA-sequentie specificiteit, wat leidt tot dosisbeperkende toxiciteit en vele bijwerkingen. Gericht op het genoom met sequentie-specifieke kleine moleculen kan moleculen met verhoogde therapeutische index en minder off-target effecten mogelijk. -methylpyrrole N / N -methylimidazole polyamiden moleculen die rationeel kunnen worden ontworpen om specifieke DNA-sequenties met uitstekende precisie richten. En in tegenstelling tot de meeste natuurlijke transcriptiefactoren, kunnen polyamiden binden aan gemethyleerd en chromatinized DNA zonder een verlies in affiniteit. De sequentie specificiteit van polyamiden is uitgebreid bestudeerd in vitro cognate locatie identificatie (CSI) en traditionele biochemische en biofysische benaderingen, maar de studie van polyamide binden aan genomisch doelen in cellen blijft ongrijpbaar. Hier beschrijven we een werkwijze het verknopen van kleine moleculen Isolate chromatine (COSMIC), dat identificeert polyamide bindende locaties in het genoom. COSMIC is vergelijkbaar met chromatine immunoprecipitatie (ChIP), maar verschilt op twee belangrijke manieren: (1) een fotocrosslinker wordt toegepast om selectief, temporeel-gestuurde opname van polyamide bindingsgebeurtenissen, en (2) het biotine affiniteit handvat wordt gebruikt om polyamide te zuiveren inschakelen -DNA conjugaten onder semi-denaturerende omstandigheden aan DNA dat niet-covalent gebonden verlagen. COSMIC is een algemene strategie die kan worden gebruikt om genoom-brede bindingsgebeurtenissen polyamiden en andere genoom-gerichte chemotherapeutische middelen te onthullen.

Introduction

De informatie om elke cel in het lichaam wordt gecodeerd in DNA. Het selectief gebruik van deze informatie bepaalt het lot van een cel. Transcriptiefactoren (TFs) zijn eiwitten die binden aan specifieke DNA-sequenties van een bepaalde subset van de genen in het genoom expressie en de storing van TF is in verband met het ontstaan van een breed scala aan ziekten, waaronder ontwikkelingsstoornissen, kanker en diabetes . 1,2 We hebben interesse in het ontwikkelen moleculen die selectief kan binden aan het genoom moduleren gen-regulerende netwerken zijn.

Polyamiden samengesteld uit N -methylpyrrole en N -methylimidazole zijn rationeel ontworpen moleculen die DNA met specificiteiten en affiniteiten die rivaliserende natuurlijke transcriptiefactoren. 3-6 Deze moleculen binden aan specifieke sequenties in de kleine groef van DNA kunnen richten. 4,5,7 -11 Polyamiden zijn gebruikt om zowel Repress en activeren van de expressie van specifieke genes. 4,12-19 Ze hebben ook interessante antivirale 20-24 en antikanker 12,13,25-30 eigenschappen. Een aantrekkelijke eigenschap van polyamiden is hun vermogen om DNA-sequenties die zijn gemethyleerd 31,32 en rond histoneiwitten 9,10,33.

Om de doorlopende bindingsspecificiteiten van DNA-bindende moleculen te meten, ons lab gemaakt de verwante plaats identifier (CSI) methode. 34-39 De voorspelde optreden van bindingsplaatsen op basis van in vitro specificiteiten (genomescapes) kan op het genoom worden weergegeven, omdat de in vitro binding intensiteiten zijn recht evenredig met associatie constanten (K a). 34,35,37 Deze genomescapes geven inzicht in polyamide bezettingsgraad over het genoom, maar het meten van polyamide verbindend in levende cellen is een uitdaging. DNA stevig verpakt in de kern, die de toegankelijkheid van bindingsplaatsen kunnen beïnvloeden. De eenccessibility van deze chromatinized DNA sequenties polyamiden blijft een mysterie.

Onlangs zijn veel methoden om wisselwerkingen tussen kleine moleculen en nucleïnezuren ontstaan bestuderen. 40-48 De chemische affiniteitsinvangmiddel en massaal parallelle DNA-sequencing (chem-seq) is een dergelijke techniek. Chem-seq gebruikt formaldehyde tot kleine moleculen verknopen een genomische doelwit van belang en een gebiotinyleerd derivaat van een klein molecuul van belang zijn voor de ligand-target interactie vangen. 48,49

Formaldehyde verknoping leidt tot indirect interacties die valse positieven produceren. 50 We ontwikkelden een nieuwe methode, de verknoping van kleine moleculen aan chromatine (COSMIC), 51 isoleren met een fotocrosslinker aan deze zogenaamde "fantoom" pieken elimineren. 50 te beginnen, We ontworpen en gesynthetiseerd trifunctionele derivaten van polyamiden. Deze moleculen bevatten een DNA-bindend polyamide een fotocrosslinker (psoraleen) en affiniteit handvat (biotine, figuur 1). Met trifunctionele polyamiden, kunnen we covalent vastleggen polyamide-DNA interacties met 365 nm UV-straling een golflengte die geen DNA wordt beschadigd of induceert zonder psoraleen-gebaseerde verknoping. 51 Vervolgens fragmenteren we het genoom en zuivert de gevangen DNA onder stringente, semi -denaturing voorwaarden DNA dat niet-covalent gebonden verlagen. Zo zien we COSMIC als een methode soortgelijk aan chem-seq, maar met een meer directe uitlezing van DNA richten. Belangrijk is dat de zwakke (Ka -10 10 3 4 M -1) affiniteit van psoraleen voor DNA niet detecteerbaar effect polyamide specificiteit. 51,52 de verrijkte DNA-fragmenten kan worden geanalyseerd met ofwel een kwantitatieve polymerasekettingreactie 51 (COSMIC-qPCR) of door het next-generation sequencing 53 (COSMIC-volgende). Deze gegevens maken een onpartijdige, genoom-geleide ontwerp van liganden die interhandelen met hun gewenste genomische loci en off-target effecten te minimaliseren.

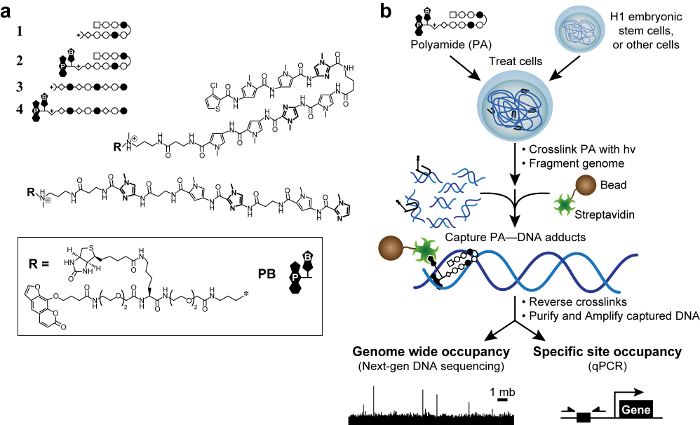

Figuur 1. Bioactieve polyamiden en kosmische plan. (A) Hairpin polyamiden 1-2 doelwit van de DNA-sequentie 5'-WACGTW-3 '. Lineaire polyamiden 3 – 4 doel 5'-AAGAAGAAG-3 '. Ringen van N-methylimidazool worden vet weergegeven voor de duidelijkheid. Open en gevulde cirkels vertegenwoordigen -methylpyrrole N en N -methylimidazole resp. Rechthoek stelt 3-chloorthiofeen en ruiten staan β-alanine. Psoralen en biotine worden aangeduid met P en B, respectievelijk. (B) kosmische plan. Cellen worden behandeld met trifunctionele afgeleiden van polyamiden. Na verknoping met 365 nm UV- bestraling cellen lysed en genomische DNA wordt geschoren. Met streptavidine beklede magnetische parels worden toegevoegd aan polyamide-DNA adducten vangen. Het DNA wordt vrijgegeven en kan worden geanalyseerd door kwantitatieve PCR (qPCR) of next-generation sequencing (NGS). Klik hier om een grotere versie van deze figuur te bekijken.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

One of the primary challenges with conventional ChIP is the identification of suitable antibodies. ChIP depends heavily upon the quality of the antibody, and most commercial antibodies are unacceptable for ChIP. In fact, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) consortium found only 20% of commercial antibodies to be suitable for ChIP assays.50 With COSMIC, antibodies are replaced by streptavidin. Because polyamides are functionalized with biotin, streptavidin is used in place of an antibody to capture polyam…

Divulgations

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Ansari lab and Prof. Parameswaran Ramanathan for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants CA133508 and HL099773, the H. I. Romnes faculty fellowship, and the W. M. Keck Medical Research Award to A.Z.A. G.S.E. was supported by a Peterson Fellowship from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biosciences Training Grant NIH T32 GM07215. A.E. was supported by the Morgridge Graduate Fellowship and the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center Fellowship, and D.B. was supported by the NSEC grant from NSF.

Materials

| Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) | any source | ||

| Benzamidine | any source | ||

| Pepstatin | any source | ||

| Proteinase K | any source | ||

| Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 | Life Technologies | 65001 | |

| PBS, pH 7.4 | Life Technologies | 10010-023 | Other sources can be used |

| StemPro® Accutase® Cell Dissociation Reagent | Life Technologies | A1110501 | |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | 28104 | We have tried other manufacturers of DNA columns with success. |

| TruSeq ChIP Sample Prep Kit | Illumina | IP-202-1012 | This Kit can be used to prepare COSMIC DNA for next-generation sequencing |

| Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix | BD Biosciences | 356231 | Used to coat plates in order to grow H1 ESCs |

| pH paper | any source | ||

| amber microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| pyrex filter | any source | Pyrex baking dishes are suitable | |

| qPCR master mix | any source | ||

| RNase | any source | ||

| HCl (6 N) | any source | ||

| 10-cm tissue culture dishes | any source | ||

| Serological pipettes | any source | ||

| Pasteur pipettes | any source | ||

| Pipette tips | any source | ||

| 15-mL conical tubes | any source | ||

| centrifuge | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge | any source | ||

| nutator | any source | ||

| Magnetic separation rack | any source | ||

| UV source | CalSun | B001BH0A1A | Other UV sources can be used, but crosslinking time must be optimized empirically |

| Misonix Sonicator | Qsonica | S4000 with 431C1 cup horn | Other sonicators can be used, but sonication conditions must be optimized empirically |

| Humidified CO2 incubator | any source | ||

| Biological safety cabinet with vacuum outlet | any source |

References

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional Regulation and Its Misregulation in Disease. Cell. 152, 1237-1251 (2013).

- Vaquerizas, J. M., Kummerfeld, S. K., Teichmann, S. A., Luscombe, N. M. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 10, 252-263 (2009).

- Meier, J. L., Yu, A. S., Korf, I., Segal, D. J., Dervan, P. B. Guiding the Design of Synthetic DNA-Binding Molecules with Massively Parallel Sequencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17814-17822 (2012).

- Dervan, P. B. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 2215-2235 (2001).

- Wemmer, D. E., Dervan, P. B. Targeting the minor groove of DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 355-361 (1997).

- Eguchi, A., Lee, G. O., Wan, F., Erwin, G. S., Ansari, A. Z. Controlling gene networks and cell fate with precision-targeted DNA-binding proteins and small-molecule-based genome readers. Biochem. J. 462, 397-413 (2014).

- Mrksich, M., et al. Antiparallel side-by-side dimeric motif for sequence-specific recognition in the minor groove of DNA by the designed peptide 1-methylimidazole-2-carboxamide netropsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 89, 7586-7590 (1992).

- Edayathumangalam, R. S., Weyermann, P., Gottesfeld, J. M., Dervan, P. B., Luger, K. Molecular recognition of the nucleosomal “supergroove”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 6864-6869 (2004).

- Suto, R. K., et al. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 371-380 (2003).

- Gottesfeld, J. M., et al. Sequence-specific Recognition of DNA in the Nucleosome by Pyrrole-Imidazole Polyamides. J. Mol. Biol. 309, 615-629 (2001).

- Chenoweth, D. M., Dervan, P. B. Structural Basis for Cyclic Py-Im Polyamide Allosteric Inhibition of Nuclear Receptor Binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14521-14529 (2010).

- Raskatov, J. A., et al. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription using programmable DNA minor groove binders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1023-1028 (2012).

- Yang, F., et al. Antitumor activity of a pyrrole-imidazole polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1863-1868 (2013).

- Mapp, A. K., Ansari, A. Z., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Activation of gene expression by small molecule transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3930-3935 (2000).

- Ansari, A. Z., Mapp, A. K., Nguyen, D. H., Dervan, P. B., Ptashne, M. Towards a minimal motif for artificial transcriptional activators. Chem. Biol. 8, 583-592 (2001).

- Arora, P. S., Ansari, A. Z., Best, T. P., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Design of artificial transcriptional activators with rigid poly-L-proline linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13067-13071 (2002).

- Nickols, N. G., Jacobs, C. S., Farkas, M. E., Dervan, P. B. Modulating Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription by Disrupting the HIF-1–DNA Interface. ACS Chemical Biology. 2, 561-571 (2007).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. A synthetic small molecule for rapid induction of multiple pluripotency genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2, 544 (2012).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. Synthetic Small Molecules for Epigenetic Activation of Pluripotency Genes in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts. Chem Bio Chem. 12, 2822-2828 (2011).

- He, G., et al. Binding studies of a large antiviral polyamide to a natural HPV sequence. Biochimie. 102, 83-91 (2014).

- Edwards, T. G., Vidmar, T. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. DNA Damage Repair Genes Controlling Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Episome Levels under Conditions of Stability and Extreme Instability. PLoS ONE. 8, e75406 (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., Helmus, M. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. HPV Episome Stability is Reduced by Aphidicolin and Controlled by DNA Damage Response Pathways. Journal of Virology. , (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., et al. HPV episome levels are potently decreased by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Antiviral Res. 91, 177-186 (2011).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription in human cells by synthetic DNA-binding ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12890-12895 (1998).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Arresting Cancer Proliferation by Small-Molecule Gene Regulation. Chem. Biol. 11, 1583-1594 (2004).

- Nickols, N. G., et al. Activity of a Py–Im Polyamide Targeted to the Estrogen Response Element. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 12, 675-684 (2013).

- Raskatov, J. A., Puckett, J. W., Dervan, P. B. A C-14 labeled Py–Im polyamide localizes to a subcutaneous prostate cancer tumor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 4371-4375 (2014).

- Jespersen, C., et al. Chromatin structure determines accessibility of a hairpin polyamide–chlorambucil conjugate at histone H4 genes in pancreatic cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 4068-4071 (2012).

- Chou, C. J., et al. Small molecules targeting histone H4 as potential therapeutics for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 7, 769-778 (2008).

- Nickols, N. G., Dervan, P. B. Suppression of androgen receptor-mediated gene expression by a sequence-specific DNA-binding polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10418-10423 (2007).

- Minoshima, M., Bando, T., Sasaki, S., Fujimoto, J., Sugiyama, H. Pyrrole-imidazole hairpin polyamides with high affinity at 5CGCG3 DNA sequence; influence of cytosine methylation on binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2889-2894 (2008).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Fabrication of duplex DNA microarrays incorporating methyl-5-cytosine. Lab on a Chip. 12, 376-380 (2012).

- Dudouet, B., et al. Accessibility of nuclear chromatin by DNA binding polyamides. Chem. Biol. 10, 859-867 (2003).

- Carlson, C. D., et al. Specificity landscapes of DNA binding molecules elucidate biological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4544-4549 (2010).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Defining the sequence-recognition profile of DNA-binding molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 867-872 (2006).

- Tietjen, J. R., Donato, L. J., Bhimisaria, D., Ansari, A. Z., Voigt, C. Chapter One – Sequence-Specificity and Energy Landscapes of DNA-Binding Molecules. Methods Enzymol. 497, 3-30 (2011).

- Puckett, J. W., et al. Quantitative microarray profiling of DNA-binding molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12310-12319 (2007).

- Keles, S., Warren, C. L., Carlson, C. D., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-Tree: a regression tree approach for modeling binding properties of DNA-binding molecules based on cognate site identification (CSI) data. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3171-3184 (2008).

- Hauschild, K. E., Stover, J. S., Boger, D. L., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-FID: High throughput label-free detection of DNA binding molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 3779-3782 (2009).

- Lee, M., Roldan, M. C., Haskell, M. K., McAdam, S. R., Hartley, J. A. . In vitro Photoinduced Cytotoxicity and DNA Binding Properties of Psoralen and Coumarin Conjugates of Netropsin Analogs: DNA Sequence-Directed Alkylation and Cross-Link. 37, 1208-1213 (1994).

- Wurtz, N. R., Dervan, P. B. Sequence specific alkylation of DNA by hairpin pyrrole–imidazole polyamide conjugates. Chem. Biol. 7, 153-161 (2000).

- Tung, S. -. Y., Hong, J. -. Y., Walz, T., Moazed, D., Liou, G. -. G. Chromatin affinity-precipitation using a small metabolic molecule: its application to analysis of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 641-650 (2012).

- Rodriguez, R., Miller, K. M. Unravelling the genomic targets of small molecules using high-throughput sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 15, 783-796 (2014).

- Guan, L., Disney, M. D. Covalent Small-Molecule–RNA Complex Formation Enables Cellular Profiling of Small-Molecule–RNA Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10010-10013 (2013).

- White, J. D., et al. Picazoplatin, an Azide-Containing Platinum(II) Derivative for Target Analysis by Click Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11680-11683 (2013).

- Rodriguez, R., et al. Small-molecule–induced DNA damage identifies alternative DNA structures in human genes. Nat Chem Biol. 8, 301-310 (2012).

- Bando, T., Sugiyama, H. Synthesis and Biological Properties of Sequence-Specific DNA-Alkylating Pyrrole−Imidazole Polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 935-944 (2006).

- Anders, L., et al. Genome-wide localization of small molecules. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 92-96 (2014).

- Jin, C., et al. Chem-seq permits identification of genomic targets of drugs against androgen receptor regulation selected by functional phenotypic screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9235-9240 (2014).

- Landt, S. G., et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Research. 22, 1813-1831 (2012).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Eguchi, A., Ansari, A. Z. Mapping Polyamide–DNA Interactions in Human Cells Reveals a New Design Strategy for Effective Targeting of Genomic Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10124-10128 (2014).

- Hyde, J. E., Hearst, J. E. Binding of psoralen derivatives to DNA and chromatin: influence of the ionic environment on dark binding and photoreactivity. Biochimie. 17, 1251-1257 (1978).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Rodríguez-Martínez, J. A., Grieshop, M. P., Ansari, A. Z. Genome-wide localization of polyamide-based genome readers reveals sequence-based binding to repressive heterochromatin. In preparation. , (2015).

- Chen, G., et al. Chemically defined conditions for human iPSC derivation and culture. Nat Meth. 8, 424-429 (2011).

- Deliard, S., Zhao, J., Xia, Q., Grant, S. F. A. Generation of High Quality Chromatin Immunoprecipitation DNA Template for High-throughput Sequencing (ChIP-seq). J Vis Exp. (74), e50286 (2013).

- Shi, Y. B., Spielmann, H. P., Hearst, J. E. Base-catalyzed reversal of a psoralen-DNA cross-link. Biochimie. 27, 5174-5178 (1988).

- Kumaresan, K. R., Hang, B., Lambert, M. W. Human Endonucleolytic Incision of DNA 3′ and 5′ to a Site-directed Psoralen Monoadduct and Interstrand. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30709-30716 (1995).

- Cimino, G. D., Shi, Y. B., Hearst, J. E. Wavelength dependence for the photoreversal of a psoralen-DNA crosslink. Biochimie. 25, 3013-3020 (1986).

- Heinz, S., et al. Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Mol. Cell. 38, 576-589 (2010).

- Zhang, Y., et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

- Kharchenko, P. V., Tolstorukov, M. Y., Park, P. J. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotech. 26, 1351-1359 (2008).

- Diamandis, E. P., Christopoulos, T. K. The biotin-(strept)avidin system: principles and applications in biotechnology. Clin. Chem. 37, 625-636 (1991).

- Martinson, H. G., True, R. J. On the mechanism of nucleosome unfolding. Biochimie. 18, 1089-1094 (1979).

- Gloss, L. M., Placek, B. J. The Effect of Salts on the Stability of the H2A−H2B Histone Dimer. Biochimie. 41, 14951-14959 (2002).

- Jackson, V. Formaldehyde Cross-Linking for Studying Nucleosomal Dynamics. Methods. 17, 125-139 (1999).

- Kasinathan, S., Orsi, G. A., Zentner, G. E., Ahmad, K., Henikoff, S. High-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites on native chromatin. Nat Meth. 11, 203-209 (2014).

- Teytelman, L., Thurtle, D. M., Rine, J., van Oudenaarden, A. Highly expressed loci are vulnerable to misleading ChIP localization of multiple unrelated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18602-18607 (2013).

- . Phantompeakqualtools home page Available from: https://www.encodeproject.org/software/phantompeakqualtools/ (2010)

- Wang, D., Lippard, S. J. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 4, 307-320 (2005).

- Hurley, L. H. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2, 188-200 (2002).