Genomvid Kartläggning av narkotika DNA interaktioner i celler med COSMIC (Tvärbindning av små molekyler att isolera Chromatin)

Summary

Identifiera de direkta målen för genom-målsökande molekyler är fortfarande en stor utmaning. För att förstå hur DNA-bindande molekyler engagera genomet har vi utvecklat en metod som bygger på tvärbindning av små molekyler för att isolera kromatin (COSMIC).

Abstract

Genomet är målet för några av de mest effektiva kemoterapeutika, men de flesta av dessa läkemedel saknar DNA-sekvens specificitet, vilket leder till dosbegränsande toxicitet och många negativa biverkningar. Targeting genomet med sekvensspecifika små molekyler kan möjliggöra molekyler med ökad terapeutisk index och färre ej åsyftade effekter. N -methylpyrrole / N -metylimidazol polyamider är molekyler som kan rationellt utformade att inrikta sig på specifika DNA-sekvenser med utsökt precision. Och till skillnad från de flesta naturliga transkriptionsfaktorer, kan polyamider binda till metylerat och chromatinized DNA utan förlust i affinitet. Den sekvensspecificitet av polyamider har studerats in vitro med besläktat platsbeskrivning (CSI) och med traditionella biokemiska och biofysiska metoder, men studiet av polyamid-bindning till genomiska mål i celler fortfarande instabil. Här rapporterar vi ett förfarande, att tvärbindningen av små molekyler isolate kromatin (COSMIC), identifierar att polyamid bindningsställen över hela genomet. COSMIC liknar kromatin immunoprecipitation (chip), men skiljer sig i två viktiga sätt: (1) en fototvärbindare utnyttjas för att möjliggöra selektiv, tidsmässigt kontrollerade infångning av polyamid bindningshändelser, och (2) biotin affinitetshandtag används för att rena polyamid -DNA konjugat enligt semi-denaturerande betingelser för att minska DNA som är icke-kovalent bunden. COSMIC är en allmän strategi som kan användas för att avslöja de genomvida bindningshändelser av polyamider och andra genom-targeting kemoterapeutiska medel.

Introduction

Den information för att göra varje cell i människokroppen är kodad i DNA. Den selektiv användning av denna information styr ödet för en cell. Transkriptionsfaktorer (TFS) är proteiner som binder till specifika DNA-sekvenser för att uttrycka en speciell undergrupp av generna i genomet, och fel på TF: er är kopplad till uppkomsten av ett brett spektrum av sjukdomar, inklusive utvecklingsdefekter, cancer och diabetes . 1,2 Vi har varit intresserade av att utveckla molekyler som selektivt kan binda till arvsmassan och modulerar genreglerande nätverk.

Polyamider som består av N -methylpyrrole och N -metylimidazol är rationellt utformade molekyler som kan rikta DNA med särdrag och tillhörighet som rivaliserande naturliga transkriptionsfaktorer. 3-6 Dessa molekyler binder till specifika sekvenser i mindre spår av DNA. 4,5,7 -11 Polyamider har använts för att både undertrycka och aktivera uttrycket av specifika genes. 4,12-19 De har också intressanta antivirala 20-24 och cancer 12,13,25-30 egenskaper. En attraktiv egenskap av polyamider är deras förmåga att få tillgång till DNA-sekvenser som är metylerade 31,32 och lindade runt histonproteiner 9,10,33.

För att mäta de omfattande bindningsspecificiteter av DNA-bindande molekyler, skapade vårt labb det besläktade platsen identifieringsmetod (CSI). 34-39 Den förutspådda förekomsten av bindningsställen baserat på in vitro-specifika förhållanden (genomescapes) kan visas på genomet, eftersom in vitro bindningsnivåer är direkt proportionell mot associationskonstanter (K a). 34,35,37 Dessa genomescapes ge insikt i polyamid beläggning över genomet, men mätning av polyamid bindande i levande celler har varit en utmaning. DNA är tätt förpackad i kärnan, som skulle kunna påverka tillgängligheten till bindningsställen. The accessibility av dessa chromatinized DNA-sekvenser till polyamider förblir ett mysterium.

Nyligen många metoder studera interaktioner mellan små molekyler och nukleinsyror har uppstått. 40-48 Den kemiska affinitetsinfångning och massivt parallella DNA-sekvensering (kem-punkter) är en sådan teknik. Chem-seq använder formaldehyd för att tvärbinda små molekyler till en genomisk mål av intresse och ett biotinylerat derivat av en liten molekyl av intresse för att fånga ligand-mål-interaktion. 48,49

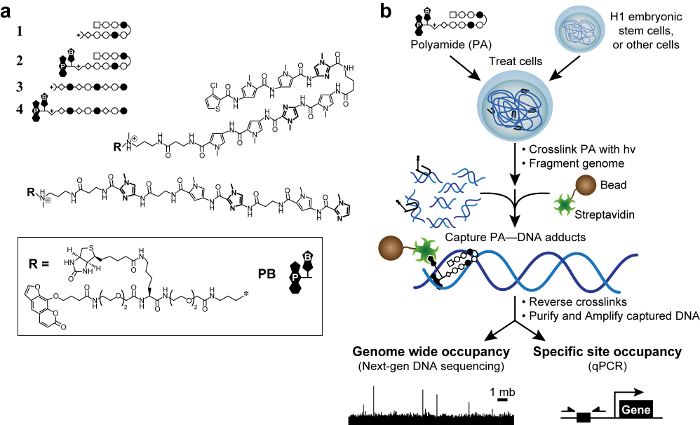

Formaldehyd tvärbindning leder till indirekt interaktion som kan producera falska positiva. 50 Vi har utvecklat en ny metod, tvärbindningen av små molekyler för att isolera kromatin (COSMIC), 51 med en fototvärbindare att eliminera dessa så kallade "fantom" toppar. 50 Till att börja, Vi designade och syntetiserade trifunktionella derivat av polyamider. Dessa molekyler innehöll en DNA-bindande polyamide, en fototvärbindare (psoralen), och en affinitetshandtag (biotin, figur 1). Med trifunktionella polyamider, kan vi kovalent fånga polyamid-DNA-interaktioner med 365 nm UV-bestrålning, en våglängd som inte skadar DNA eller förorsaka icke psoralen-baserade tvärbindning. 51 Nästa, vi fragmentera genomet och rena den infångade DNA under stringenta, semi -denaturing betingelser för att minska DNA som är icke-kovalent bunden. Därför ser vi COSMIC som en metod i samband med kemiska-punkter, men med en mer direkt avläsning av DNA inriktning. Viktigt är att svaga (K 10 3 -10 4 M -1) affinitet psoralen för DNA inte påvisbart påverkan polyamid specificitet. 51,52 De anrikade DNA-fragment kan analyseras antingen genom kvantitativ polymerase chain reaction 51 (COSMIC-qPCR) eller genom nästa generations sekvensering 53 (COSMIC-punkter). Dessa uppgifter möjliggöra en opartisk, genom styrd utformning av ligander som interhandla med deras önskade genomiska loci och minimera off-target effekter.

Figur 1. Bioaktiva polyamider och kosmisk ordning. (A) hårnål polyamider 1-2 målgrupp DNA-sekvensen 5'-WACGTW-3 '. Linjära polyamider 3-4 målgrupp 5'-AAGAAGAAG-3 '. Ringar av N-metylimidazol är i fetstil för tydlighets skull. Öppna och fyllda cirklar representerar N -methylpyrrole och N metylimidazol, respektive. Square representerar 3-klortiofen och diamanter representerar β-alanin. Psoralen och biotin betecknas med P och B, respektive. (B) KOSMISK system. Celler behandlas med trifunktionella derivat av polyamider. Efter tvärbindning med 365 nm UV-bestrålning, celler är lysed och genomisk DNA klippt. Streptavidinbelagda magnetiska pärlor tillsätts för att fånga polyamid-DNA-addukter. DNA frigörs och kan analyseras med kvantitativ PCR (qPCR) eller genom nästa generations sekvensering (NGS). Klicka här för att se en större version av denna siffra.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

One of the primary challenges with conventional ChIP is the identification of suitable antibodies. ChIP depends heavily upon the quality of the antibody, and most commercial antibodies are unacceptable for ChIP. In fact, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) consortium found only 20% of commercial antibodies to be suitable for ChIP assays.50 With COSMIC, antibodies are replaced by streptavidin. Because polyamides are functionalized with biotin, streptavidin is used in place of an antibody to capture polyam…

Divulgations

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Ansari lab and Prof. Parameswaran Ramanathan for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants CA133508 and HL099773, the H. I. Romnes faculty fellowship, and the W. M. Keck Medical Research Award to A.Z.A. G.S.E. was supported by a Peterson Fellowship from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biosciences Training Grant NIH T32 GM07215. A.E. was supported by the Morgridge Graduate Fellowship and the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center Fellowship, and D.B. was supported by the NSEC grant from NSF.

Materials

| Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) | any source | ||

| Benzamidine | any source | ||

| Pepstatin | any source | ||

| Proteinase K | any source | ||

| Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 | Life Technologies | 65001 | |

| PBS, pH 7.4 | Life Technologies | 10010-023 | Other sources can be used |

| StemPro® Accutase® Cell Dissociation Reagent | Life Technologies | A1110501 | |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | 28104 | We have tried other manufacturers of DNA columns with success. |

| TruSeq ChIP Sample Prep Kit | Illumina | IP-202-1012 | This Kit can be used to prepare COSMIC DNA for next-generation sequencing |

| Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix | BD Biosciences | 356231 | Used to coat plates in order to grow H1 ESCs |

| pH paper | any source | ||

| amber microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| pyrex filter | any source | Pyrex baking dishes are suitable | |

| qPCR master mix | any source | ||

| RNase | any source | ||

| HCl (6 N) | any source | ||

| 10-cm tissue culture dishes | any source | ||

| Serological pipettes | any source | ||

| Pasteur pipettes | any source | ||

| Pipette tips | any source | ||

| 15-mL conical tubes | any source | ||

| centrifuge | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge | any source | ||

| nutator | any source | ||

| Magnetic separation rack | any source | ||

| UV source | CalSun | B001BH0A1A | Other UV sources can be used, but crosslinking time must be optimized empirically |

| Misonix Sonicator | Qsonica | S4000 with 431C1 cup horn | Other sonicators can be used, but sonication conditions must be optimized empirically |

| Humidified CO2 incubator | any source | ||

| Biological safety cabinet with vacuum outlet | any source |

References

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional Regulation and Its Misregulation in Disease. Cell. 152, 1237-1251 (2013).

- Vaquerizas, J. M., Kummerfeld, S. K., Teichmann, S. A., Luscombe, N. M. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 10, 252-263 (2009).

- Meier, J. L., Yu, A. S., Korf, I., Segal, D. J., Dervan, P. B. Guiding the Design of Synthetic DNA-Binding Molecules with Massively Parallel Sequencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17814-17822 (2012).

- Dervan, P. B. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 2215-2235 (2001).

- Wemmer, D. E., Dervan, P. B. Targeting the minor groove of DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 355-361 (1997).

- Eguchi, A., Lee, G. O., Wan, F., Erwin, G. S., Ansari, A. Z. Controlling gene networks and cell fate with precision-targeted DNA-binding proteins and small-molecule-based genome readers. Biochem. J. 462, 397-413 (2014).

- Mrksich, M., et al. Antiparallel side-by-side dimeric motif for sequence-specific recognition in the minor groove of DNA by the designed peptide 1-methylimidazole-2-carboxamide netropsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 89, 7586-7590 (1992).

- Edayathumangalam, R. S., Weyermann, P., Gottesfeld, J. M., Dervan, P. B., Luger, K. Molecular recognition of the nucleosomal “supergroove”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 6864-6869 (2004).

- Suto, R. K., et al. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 371-380 (2003).

- Gottesfeld, J. M., et al. Sequence-specific Recognition of DNA in the Nucleosome by Pyrrole-Imidazole Polyamides. J. Mol. Biol. 309, 615-629 (2001).

- Chenoweth, D. M., Dervan, P. B. Structural Basis for Cyclic Py-Im Polyamide Allosteric Inhibition of Nuclear Receptor Binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14521-14529 (2010).

- Raskatov, J. A., et al. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription using programmable DNA minor groove binders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1023-1028 (2012).

- Yang, F., et al. Antitumor activity of a pyrrole-imidazole polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1863-1868 (2013).

- Mapp, A. K., Ansari, A. Z., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Activation of gene expression by small molecule transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3930-3935 (2000).

- Ansari, A. Z., Mapp, A. K., Nguyen, D. H., Dervan, P. B., Ptashne, M. Towards a minimal motif for artificial transcriptional activators. Chem. Biol. 8, 583-592 (2001).

- Arora, P. S., Ansari, A. Z., Best, T. P., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Design of artificial transcriptional activators with rigid poly-L-proline linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13067-13071 (2002).

- Nickols, N. G., Jacobs, C. S., Farkas, M. E., Dervan, P. B. Modulating Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription by Disrupting the HIF-1–DNA Interface. ACS Chemical Biology. 2, 561-571 (2007).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. A synthetic small molecule for rapid induction of multiple pluripotency genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2, 544 (2012).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. Synthetic Small Molecules for Epigenetic Activation of Pluripotency Genes in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts. Chem Bio Chem. 12, 2822-2828 (2011).

- He, G., et al. Binding studies of a large antiviral polyamide to a natural HPV sequence. Biochimie. 102, 83-91 (2014).

- Edwards, T. G., Vidmar, T. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. DNA Damage Repair Genes Controlling Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Episome Levels under Conditions of Stability and Extreme Instability. PLoS ONE. 8, e75406 (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., Helmus, M. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. HPV Episome Stability is Reduced by Aphidicolin and Controlled by DNA Damage Response Pathways. Journal of Virology. , (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., et al. HPV episome levels are potently decreased by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Antiviral Res. 91, 177-186 (2011).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription in human cells by synthetic DNA-binding ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12890-12895 (1998).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Arresting Cancer Proliferation by Small-Molecule Gene Regulation. Chem. Biol. 11, 1583-1594 (2004).

- Nickols, N. G., et al. Activity of a Py–Im Polyamide Targeted to the Estrogen Response Element. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 12, 675-684 (2013).

- Raskatov, J. A., Puckett, J. W., Dervan, P. B. A C-14 labeled Py–Im polyamide localizes to a subcutaneous prostate cancer tumor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 4371-4375 (2014).

- Jespersen, C., et al. Chromatin structure determines accessibility of a hairpin polyamide–chlorambucil conjugate at histone H4 genes in pancreatic cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 4068-4071 (2012).

- Chou, C. J., et al. Small molecules targeting histone H4 as potential therapeutics for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 7, 769-778 (2008).

- Nickols, N. G., Dervan, P. B. Suppression of androgen receptor-mediated gene expression by a sequence-specific DNA-binding polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10418-10423 (2007).

- Minoshima, M., Bando, T., Sasaki, S., Fujimoto, J., Sugiyama, H. Pyrrole-imidazole hairpin polyamides with high affinity at 5CGCG3 DNA sequence; influence of cytosine methylation on binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2889-2894 (2008).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Fabrication of duplex DNA microarrays incorporating methyl-5-cytosine. Lab on a Chip. 12, 376-380 (2012).

- Dudouet, B., et al. Accessibility of nuclear chromatin by DNA binding polyamides. Chem. Biol. 10, 859-867 (2003).

- Carlson, C. D., et al. Specificity landscapes of DNA binding molecules elucidate biological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4544-4549 (2010).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Defining the sequence-recognition profile of DNA-binding molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 867-872 (2006).

- Tietjen, J. R., Donato, L. J., Bhimisaria, D., Ansari, A. Z., Voigt, C. Chapter One – Sequence-Specificity and Energy Landscapes of DNA-Binding Molecules. Methods Enzymol. 497, 3-30 (2011).

- Puckett, J. W., et al. Quantitative microarray profiling of DNA-binding molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12310-12319 (2007).

- Keles, S., Warren, C. L., Carlson, C. D., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-Tree: a regression tree approach for modeling binding properties of DNA-binding molecules based on cognate site identification (CSI) data. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3171-3184 (2008).

- Hauschild, K. E., Stover, J. S., Boger, D. L., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-FID: High throughput label-free detection of DNA binding molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 3779-3782 (2009).

- Lee, M., Roldan, M. C., Haskell, M. K., McAdam, S. R., Hartley, J. A. . In vitro Photoinduced Cytotoxicity and DNA Binding Properties of Psoralen and Coumarin Conjugates of Netropsin Analogs: DNA Sequence-Directed Alkylation and Cross-Link. 37, 1208-1213 (1994).

- Wurtz, N. R., Dervan, P. B. Sequence specific alkylation of DNA by hairpin pyrrole–imidazole polyamide conjugates. Chem. Biol. 7, 153-161 (2000).

- Tung, S. -. Y., Hong, J. -. Y., Walz, T., Moazed, D., Liou, G. -. G. Chromatin affinity-precipitation using a small metabolic molecule: its application to analysis of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 641-650 (2012).

- Rodriguez, R., Miller, K. M. Unravelling the genomic targets of small molecules using high-throughput sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 15, 783-796 (2014).

- Guan, L., Disney, M. D. Covalent Small-Molecule–RNA Complex Formation Enables Cellular Profiling of Small-Molecule–RNA Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10010-10013 (2013).

- White, J. D., et al. Picazoplatin, an Azide-Containing Platinum(II) Derivative for Target Analysis by Click Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11680-11683 (2013).

- Rodriguez, R., et al. Small-molecule–induced DNA damage identifies alternative DNA structures in human genes. Nat Chem Biol. 8, 301-310 (2012).

- Bando, T., Sugiyama, H. Synthesis and Biological Properties of Sequence-Specific DNA-Alkylating Pyrrole−Imidazole Polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 935-944 (2006).

- Anders, L., et al. Genome-wide localization of small molecules. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 92-96 (2014).

- Jin, C., et al. Chem-seq permits identification of genomic targets of drugs against androgen receptor regulation selected by functional phenotypic screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9235-9240 (2014).

- Landt, S. G., et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Research. 22, 1813-1831 (2012).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Eguchi, A., Ansari, A. Z. Mapping Polyamide–DNA Interactions in Human Cells Reveals a New Design Strategy for Effective Targeting of Genomic Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10124-10128 (2014).

- Hyde, J. E., Hearst, J. E. Binding of psoralen derivatives to DNA and chromatin: influence of the ionic environment on dark binding and photoreactivity. Biochimie. 17, 1251-1257 (1978).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Rodríguez-Martínez, J. A., Grieshop, M. P., Ansari, A. Z. Genome-wide localization of polyamide-based genome readers reveals sequence-based binding to repressive heterochromatin. In preparation. , (2015).

- Chen, G., et al. Chemically defined conditions for human iPSC derivation and culture. Nat Meth. 8, 424-429 (2011).

- Deliard, S., Zhao, J., Xia, Q., Grant, S. F. A. Generation of High Quality Chromatin Immunoprecipitation DNA Template for High-throughput Sequencing (ChIP-seq). J Vis Exp. (74), e50286 (2013).

- Shi, Y. B., Spielmann, H. P., Hearst, J. E. Base-catalyzed reversal of a psoralen-DNA cross-link. Biochimie. 27, 5174-5178 (1988).

- Kumaresan, K. R., Hang, B., Lambert, M. W. Human Endonucleolytic Incision of DNA 3′ and 5′ to a Site-directed Psoralen Monoadduct and Interstrand. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30709-30716 (1995).

- Cimino, G. D., Shi, Y. B., Hearst, J. E. Wavelength dependence for the photoreversal of a psoralen-DNA crosslink. Biochimie. 25, 3013-3020 (1986).

- Heinz, S., et al. Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Mol. Cell. 38, 576-589 (2010).

- Zhang, Y., et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

- Kharchenko, P. V., Tolstorukov, M. Y., Park, P. J. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotech. 26, 1351-1359 (2008).

- Diamandis, E. P., Christopoulos, T. K. The biotin-(strept)avidin system: principles and applications in biotechnology. Clin. Chem. 37, 625-636 (1991).

- Martinson, H. G., True, R. J. On the mechanism of nucleosome unfolding. Biochimie. 18, 1089-1094 (1979).

- Gloss, L. M., Placek, B. J. The Effect of Salts on the Stability of the H2A−H2B Histone Dimer. Biochimie. 41, 14951-14959 (2002).

- Jackson, V. Formaldehyde Cross-Linking for Studying Nucleosomal Dynamics. Methods. 17, 125-139 (1999).

- Kasinathan, S., Orsi, G. A., Zentner, G. E., Ahmad, K., Henikoff, S. High-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites on native chromatin. Nat Meth. 11, 203-209 (2014).

- Teytelman, L., Thurtle, D. M., Rine, J., van Oudenaarden, A. Highly expressed loci are vulnerable to misleading ChIP localization of multiple unrelated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18602-18607 (2013).

- . Phantompeakqualtools home page Available from: https://www.encodeproject.org/software/phantompeakqualtools/ (2010)

- Wang, D., Lippard, S. J. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 4, 307-320 (2005).

- Hurley, L. H. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2, 188-200 (2002).