扫描电子显微镜(SEM)协议有问题的工厂,卵菌和真菌样本

Summary

Problems in the processing of biological samples for scanning electron microscopy observation include cell collapse, treatment of samples from wet microenvironments and cell destruction. Low-cost and relatively rapid protocols suited for preparing challenging samples such as floral meristems, oomycete cysts, and fungi (Agaricales) are compiled and detailed here.

Abstract

在生物样品的用于与扫描型电子显微镜(SEM)的观察处理常见的问题包括细胞崩溃,治疗从湿微环境和细胞破坏样品。用年轻的花组织,卵菌囊肿,真菌孢子(伞菌)为例,具体的协议来处理这里描述了克服一些在样品处理的SEM下图像采集的主要挑战细腻的样本。

固定FAA花分生组织(福尔马林乙醇),并与临界点干燥机(CPD)进行处理并没有显示倒塌细胞壁内或扭曲器官。这些结果对于花发育的重建的关键。从湿微环境,如戊二醛固定的卵菌囊肿样品的类似的基于CPD处理,是最佳的,以测试的诊断特征在不同类型的su差动生长( 例如,囊肿刺)bstrates。补液,脱水和CPD处理,这些细胞的进一步的功能研究的一个重要步骤后避免附着到真菌孢子护士细胞的破坏。

这里详细的协议代表了低成本和收购的良好品质的图像重建生长过程和研究诊断的特点迅速的替代品。

Introduction

在生物学上,利用扫描电子显微镜(SEM)已经扩展到构造演化,比较形态学,器官发育,以及人口或物种1表征的研究。随着微观结构的二维视图,如微观和系统学区从SEM技术的进步,因为在20 世纪下半叶获利。例如,引入在20世纪70年代的溅射镀膜方法制成精巧的材料可能观测诸如茎尖和花增强非导电组织2,3的摄像。 SEM使用从试样的表面喷出重现地形在高真空环境中4个电子。

在涉及SEM研究主要集中在结构特征既推理和growt重建^ h的进程。而相关的分类结构的新字符的范围广泛的生物系统学已经从SEM的观察发现。例如,用于物种诊断或supraspecific分类植物性状,如木材5,柱头多样性6,蜜腺和花形态7,8,毛状体细节9和花粉的笼罩下的凹坑10,11,将不能正确而不可视SEM。与传统的SEM观察的成功已经也实现了长期福尔马林固定的生物体12和植物腊叶标本13。

在另一方面,利用扫描电镜生长过程重构研究涉及广泛的议题,如器官发育14的INFE由细菌15,植物根系生理16,寄生虫主机连接机构17,18日 ,寄生虫19,重寄生和抗菌20,21,生长畸形22,野生型和突变的个体23的比较发展和整个生命周期的药物作用引起的ctions 24。虽然环境扫描电子显微镜(ESEM)25可以具有重要的优点为湿的生物样品在生长过程中的观察,细腻的材料仍然可以甚至在ESEM)的低真空条件损害,并且需要适当地处理,以避免损失宝贵的形态学观察。

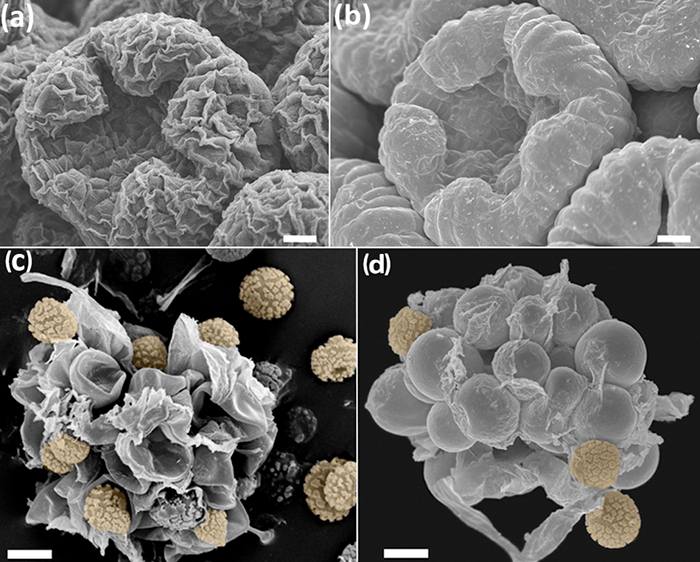

在本文中,具体的协议三种差异的SEM观察审查erent类型的样品,提出:花分生组织,卵菌( 水霉 )和真菌的材料。这些协议编译我们以前基于SEM研究26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,其中的具体困难和替代解决方案已经发现的经验。在植物发育的比较和结构研究的情况下,利用SEM起步于上世纪70年代34,35,从那时起,研究人员发现,某些花的特点是比以前认为的36更不稳定。花发育的改造涉及到年轻的花分生组织和花之间的所有阶段的捕获。为了达到这个目的,它是ESSE微分方程边值问题的样品形貌和细胞壁完整性固定和随后的脱水后,不会受到损害。年轻的花分生组织特别容易被细胞壁塌陷( 图1a,1b)。同样,结构精细,如蜜腺,花瓣,柱头和孢子囊需要有效和undamaging协议。本文总结了一个最佳的方案,以保持娇嫩的组织完好SEM成像。

在卵菌(原生藻菌)寄生虫最多样化的和广泛的基团的酮,与主机从微生物和植物,以无脊椎动物和脊椎动物37的情况下-有一些生长和在潮湿环境中培养孢子。这一条件表示为SEM观察的挑战,因为孢子需要适当的衬底不适合标准的SEM协议。间的卵菌纲, 水霉的种是特别感兴趣的,因为它们的Cañ引起aquacultures,渔业和两栖动物数量严重38减少。微形态特征,如包囊的钩状刺,已发现是确定水霉,这是基本的,以建立感染的控制和潜在的治疗39的种类是有用的。这里,有一个实验方案来比较包囊在不同基材上的脊柱生长的图案和操纵为临界点干燥器(CPD)制备和随后的SEM观察样品。

在第三情况下,存在的真菌Phellorinia herculanea f的孢子的检查之后想出有趣的发现。 斯泰拉塔 F。新星(伞菌)31。连同孢子,一组苗圃意外的细胞是在SEM下确定的。与以往传统的协议和未经处理的材料,护士进来细胞欧ŧ完全坍塌( 图1c)。关于相关的孢子特定组织进一步推论可以用简单但重要的修改,以这里所描述( 图1d)的标准方法进行。

在该评价中,有可以使用的处理与在SEM观察相关联的不同问题的详细SEM协议被子植物,卵菌和伞菌,如细胞瓦解和分生组织萎缩,囊肿棘非最优生长,破坏短暂的组织,分别为。

图1:无(A,C)和(B,D)的协议,FAA -乙醇- CPD处理样品的比较。 (A – B)Anacyclus棒曲霉,中期发展的花蕾。芽四氧化锇46 <处理/ SUP>( 一 )和巴德与FAA-CPD协议( 二 )处理。 (C – D)护士细胞Phellorinia herculanea的F孢子。 斯泰拉塔。干燥的样品未经任何处理(c)和与伞菌( 四 )这里所描述的协议。孢子为橙色。秤:(AB)100微米,(CD)为50μm。照片是采取Y.鲁伊斯 – 莱昂。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

相对于标准的SEM协议,这里提出的步骤包括相对快速的,容易执行,和低成本的方法。取决于样品的量和在便于加工,需要四到五天以获得良好质量的图像。包括为CPD和SEM的操作足够的安全预防措施,程序很容易处理。尤其应谨慎用福尔马林和戊二醛采取(参见1.1.1步骤1.1.3来和协议的2.1.5)。有一定的步骤,其中,如果需要的话,该过程可以停止一段长的时间,而不会损坏样品或破坏前面的步骤?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

该项目号634429.本刊物只反映作者本人的观点赠款协议下收到的资金来自欧盟的地平线2020年研究和创新计划,以及欧洲委员会不能承担责任可能作出的任何信息使用所载。我们也承认在真正的哈尔丁植物园,中船重工做出的财政贡献。 SR感谢欧盟[ITN-SAPRO-238550]为支持她的水霉的研究。我们还要感谢旧金山德卡隆赫友好地处理样品(图5)提供Phellorinia herculanea图像和B.普埃约。所有图像都采取了在Real哈尔丁植物园 – 中国船舶重工集团公司在马德里的SEM服务。

Materials

| Acetic acid | No specific supplier | Skin irritation, eye irritation | |

| aluminium stubs | Ted Pella, Inc. | 16221 | www.tedpella.com |

| Centrifuge tubes | No specific supplier | ||

| Critical Point Dryer | Polaron Quatum Technologies | CPD7501 | |

| D (+) Glucose | Merck | 1,083,421,000 | |

| Double sided sellotape | No specific supplier | ||

| Ethanol absolute | No specific supplier. | Flammable | |

| European bacteriological agar | Conda | 1800.00 | www.condalab.com |

| Filter paper | No specific supplier | ||

| Forceps | No specific supplier | ||

| Formalin 4% | No specific supplier. | Harmful, acute toxicity, skin sensitisation, carcinogenicity. Flammable | |

| Glass cover slips | No specific supplier | ||

| Glass hermetic container | No specific supplier | ||

| Glutaraldehyde 25% DC 253857.1611 (L) | Dismadel S.L. | 3336 | www.dismadel.com |

| Mycological peptone | Conda | 1922.00 | www.condalab.com |

| needles | No specific supplier | ||

| Petri dishes | No specific supplier | ||

| Plastic containers | No specific supplier | ||

| Sample holder with lid for the critical point dryer | Ted Pella, Inc. | 4591 | www.tedpella.com |

| scalpels | No specific supplier | ||

| Scanning Electron Microscope | Hitachi | S3000N | |

| Software for SEM | |||

| Solution A: NaH2PO4 | |||

| Solution B: Na2HPO4 | |||

| Specimen holders | No specific supplier | ||

| Sputter coater | Balzers | SCD 004 | |

| Stereomicroscope | No specific supplier | ||

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) grids | Electron Microscopy Sciences | G200 (Square Mesh) | www.emsdiassum.com |

| Tweezers | No specific supplier |

References

- Endress, P. K., Baas, P., Gregory, M. Systematic plant morphology and anatomy: 50 years of progress. Taxon. 49 (3), 401-434 (2000).

- Falk, R. H., Gifford, E. M., Cutter, E. G. Scanning electron microscopy of developing plant organs. Science. 168 (3938), 1471-1474 (1970).

- Damblon, F. Sputtering, a new method of coating pollen grains in scanning electron microscopy. Grana. 15 (3), 137-144 (1975).

- Everhart, T. E., Thornley, R. F. M. Wide-band detector for micro-microampere low-energy electron currents. J. Sci. Instrum. 37 (7), 37246-37248 (1960).

- Collins, S. P., et al. Advantages of environmental scanning electron microscopy in studies of microorganisms. Microsc. Res. Techniq. 25 (5-6), 398-405 (1993).

- Fannes, W., Vanhove, M. P. M., Huyse, T., Paladini, G. A scanning electron microscope technique for studying the sclerites of Cichlidogyrus. Parasitol. Res. 114 (5), 2031-2034 (2015).

- Erbar, C., Leins, P. Portioned pollen release and the syndromes of secondary pollen presentation in the Campanulales-Asterales complex. Flora. 190 (4), 323-338 (1995).

- Jansen, S., Smets, E., Baas, P. Vestures in woody plants: a review. IAWA Journal. 19 (4), 347-382 (1998).

- Bortolin Costa, M. F., et al. Stigma diversity in tropical legumes with considerations on stigma classification. Bot. Rev. 80 (1), 1-29 (2014).

- Almeida, O. J. G., Cota-Sánchez, J. H., Paoli, A. A. S. The systematic significance of floral morphology, nectaries, and nectar concentration in epiphytic cacti of tribes Hylocereeae and Rhipsalideae (Cactaceae). Perspect. Plant Ecol. 15 (5), 255-268 (2013).

- Konarska, A. Comparison of the structure of floral nectaries in two Euonymus L. species (Celastraceae). Protoplasma. 252 (3), 901-910 (2015).

- Giuliani, C., Maleci Bini, L. Insight into the structure and chemistry of glandular trichomes of Labiatae, with emphasis on subfamily Lamioideae. Plant Syst. Evol. 276 (3-4), 199-208 (2008).

- Li, K., Zheng, B., Wang, Y., Zhou, L. L.Breeding system and pollination biology of Paeonia delavayi (Paeoniaceae), an endangered plant in the Southwest of China. Pak. J. Bot. 46 (5), 1631-1642 (2014).

- García, L., Rivero, M., Droppelmann, F. Descripción morfológica y viabilidad del polen de Nothofagus nervosa (Nothofagaceae). Bosque. 36 (3), 487-496 (2015).

- Prenner, G., Klitgaard, B. B. Towards unlocking the deep nodes of Leguminosae: floral development and morphology of the enigmatic Duparquetia orchidacea (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae). Am. J. Bot. 95 (11), 1349-1365 (2008).

- Ratnayake, K., Joyce, D. C., Webb, R. I. A convenient sample preparation protocol for scanning electron microscope examination of xylem-occluding bacterial biofilm on cut flowers and foliage. Sci. Hortic-Amsterdam. 140 (1), 12-18 (2012).

- Çolak, G., Celalettin Baykul, M., Gürler, R., Çatak, E., Caner, N. Investigation of the effects of aluminium stress on some macro and micro-nutrient contents of the seedlings of Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. by using scanning electron microscope. Pak. J. Bot. 46 (1), 147-160 (2014).

- Arafa, S. Z. Scanning electron microscope observations on the monogenean parasite Paraquadriacanthus nasalis from the nasal cavities of the freshwater fish Clarias gariepinus in Egypt with a note on some surface features of its microhabitat. Parasitol. Res. 110 (5), 1687-1693 (2012).

- Uppalapatia, S. R., Kerwinb, J. L., Fujitac, Y. Epifluorescence and scanning electron microscopy of host-pathogen interactions between Pythium porphyrae (Peronosporales, Oomycota)and Porphyra yezoensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Bot. Mar. 44 (2), 139-145 (2001).

- Meaney, M., Haughey, S., Brennan, G. P., Fairweather, I. A scanning electron microscope study on the route of entry of clorsulon into the liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica. Parasitol. Res. 95 (2), 117-128 (2005).

- Sundarasekar, J., Sahgal, G., Subramaniam, S. Anti-candida activity by Hymenocallis littoralis extracts for opportunistic oral and genital infection Candida albicans. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 7 (3), 211-216 (2012).

- Benhamou, N., Rey, P., Picard, K., Tirilly, Y. Ultrastructural and cytochemical aspects of the interaction between the mycoparasite Pythium oligandrum and soilborne plant pathogens. Phytopathology. 89 (6), 506-517 (1999).

- Singh, A., et al. First evidence of putrescine involvement in mitigating the floral malformation in mangoes: A scanning electron microscope study. Protoplasma. 251 (5), 1255-1261 (2014).

- Xiang, C., et al. Fine mapping of a palea defective 1 (pd1), a locus associated with palea and stamen development in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 34 (12), 2151-2159 (2015).

- Mendoza, L., Hernandez, F., Ajello, L. Life cycle of the human and animal oomycete pathogen Pythium insidiosum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31 (11), 2967-2973 (1993).

- Bello, M. A., Rudall, P. J., González, F., Fernández, J. L. Floral morphology and development in Aragoa (Plantaginaceae) andrelated members of the order Lamiales. Int. J. Plant Sci. 165 (5), 723-738 (2004).

- Bello, M. A., Hawkins, J. A., Rudall, P. J. Floral morphology and development in Quillajaceae and Surianaceae (Fabales), the species-poor relatives of Leguminosae and Polygalaceae. Ann. Bot. 100 (4), 1491-1505 (2007).

- Bello, M. A., Hawkins, J. A., Rudall, P. J. Floral ontogeny in Polygalaceae and its bearing on the homologies of keeled flowers in Fabales. Int. J. Plant Sci. 171 (5), 482-498 (2010).

- Bello, M. A., Alvarez, I., Torices, R., Fuertes-Aguilar, J. Floral development and evolution of capitulum structure in Anacyclus (Anthemideae, Asteraceae). Ann. Bot. 112 (8), 1597-1612 (2013).

- Bello, M. A., Martínez-Asperilla, A., Fuertes-Aguilar, J. Floral development of Lavatera trimestris and Malva hispanica reveals the nature of the epicalyx in the Malva generic alliance. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 181 (1), 84-98 (2016).

- Calonge, F. D., Martínez, A. J., Falcó, I., Samper, L. E. Phellorinia herculanea f. stellata f. nova encontrada en España. Bol. Soc. Micol.Madrid. 35 (1), 65-70 (2011).

- Liu, Y., et al. Deciphering microbial landscapes of fish eggs to mitigate emerging diseases. ISME J. 8 (10), 2002-2014 (2014).

- Sandoval-Sierra, J. V., Diéguez-Uribeondo, J. A comprehensive protocol for improving the description of Saprolegniales (Oomycota): two practical examples (Saprolegnia aenigmatica sp. nov. and Saprolegnia racemosa sp. nov.). PLOS one. , (2015).

- Endress, P. K. Zur vergleichenden Entwicklungsmorphologie, Embryologie und Systematik bei Laurales. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 92 (2), 331-428 (1972).

- Tucker, S. Floral development in Saururus cernuus (Saururaceae):1. Floral initiation and stamen development. Am. J. Bot. 62 (3), 993-1005 (1975).

- Endress, P. K., Matthews, M. L. Progress and problems in the assessment of flower morphology in higher-level systematics. Plant Syst. Evol. 298 (2), 257-276 (2012).

- Beakes, G. W., Glockling, S. L., Sekimoto, S. The evolutionary phylogeny of the oomycete "fungi". Protoplasma. 249 (1), 3-19 (2012).

- Romansic, J. M., et al. Effects of the pathogenic water mold Saprolegnia ferax on survival of amphibian larvae. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 83 (3), 187-193 (2009).

- van West, P. Saprolegnia parasitica, an oomycete pathogen with a fishy appetite: new challengues for an old problem. Mycologist. 20 (3), 99-104 (2006).

- Johansen, D. A. . Plant microtechnique. , (1940).

- Unestam, T. Studies on the crayfish plague fungus Aphanomyces astaci. Some factors affecting growth in vitro. Physiol. Plantarum. 18 (2), 483-505 (1965).

- Cerenius, L., Söderhäll, K. Repeated zoospore emergence from isolated spore cysts of Aphanomyces astaci. Exp. Mycol. 8 (4), 370-377 (1984).

- Diéguez-Uribeondo, J., Cerenius, L., Söderhäll, K. Repeated zoospore emergence in Saprolegnia parasitica. Mycol. Res. 98 (7), 810-815 (1994).

- Söderhäll, K., Svensson, E., Unestam, T. Chitinase and protease activities in germinating zoospore cysts of a parasitic fungus, Aphanomyces astaci, Oomycetes. Mycopathologia. 64 (1), 9-11 (1978).

- Echlin, P. . Handbook of sample preparation for scanning electron microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis. , (2009).

- Osumi, M., et al. Preparation for observation of fine structure of biological specimens by high-resolution SEM. Microscopy. 32 (4), 321-330 (1983).

- Rezinciuc, S. . The Saprolegniales morpho-molecular puzzle: an insight into markers identifying specific and subspecific levels in main parasites. , (2013).