触觉半自动被动手指角刺激器 (TSPAS)

Summary

呈现的是触觉半自动被动手指角刺激器 TSPAS,这是一种使用计算机控制的触觉刺激系统来评估触觉空间敏锐度和触觉角度辨别的新方法,该系统将凸起角度刺激应用到受试者的被动指垫上,同时控制运动速度、距离和接触时间。

Abstract

被动触觉感知是被动和静态感知来自皮肤的刺激信息的能力:例如,感知空间信息的能力是手部皮肤中最强的。这种能力被称为触觉空间敏锐度,由触觉阈值或歧视阈值来衡量。目前,两点阈值被广泛用作触觉空间敏锐性的衡量标准,尽管许多研究表明,两点歧视存在严重缺陷。因此,开发了计算机控制的触觉刺激系统,即触觉半自动被动手指角刺激器(TSPAS),利用触觉角度辨别阈值作为触觉空间敏锐度的新尺度。TSPAS 是一种简单易于操作的系统,在控制运动速度、距离和接触时间的同时,将凸起的角度刺激应用于受试者的被动指垫。TSPAS 的组件详细描述了计算触觉角度歧视阈值的程序。

Introduction

触摸感知是体感觉系统处理的感觉的基本形式,包括触觉感知和触觉感知。被动触觉感知,而不是主动探索,意味着物体被移动,使接触静态皮肤1,2。与其他意义上的触觉一样,触觉中的空间分辨率,也称为触觉空间敏锐度,通常以触觉阈值、检测阈值或歧视阈值2、3表示。在过去的100年里,两分阈值通常被用作触觉空间敏锐度4的衡量标准。然而,许多研究表明,两点阈值是触觉空间能力的无效索引,因为两点歧视(TPD)不能排除非空间线索(例如,如果两点太近,他们可能会找到一个容易引起神经活动增加的单一受体场),并维持一个稳定的响应标准3,4,5。由于TPD的缺点,已经开发了几种新的和有前途的方法作为替代品,如触觉光栅方向(GO)3,6,两点方向歧视5,提高字母识别,间隙检测7,点模式,兰多特C环8,角歧视(AD)9,10。目前,由于操作GO的优势,以及空间结构和使用的刺激的复杂性,GO越来越多地用于测量触觉空间敏锐度11,12,13。

虽然触觉 GO 被认为依赖于底层空间机制,从而产生了对触觉空间敏锐性的可靠测量,但 GO 性能是否部分受非空间提示14的影响(例如,可能提供识别方向刺激差异的提示的密集迹象)仍存在争议。此外,GO仅包括简单的空间定向(即水平和垂直)任务,主要涉及感官处理,这限制了它在探索主体体感觉皮层中的触觉初级处理和触觉高级拥有之间的层次相互作用,涉及后皮层皮层(PPC)和超毛陀螺(SMG)15,16,17。为了弥补这些缺点,触觉广告被开发用于测量触觉空间敏锐度9,10。在 AD 中,一对角度被动地滑过指尖。角度在大小上有所不同,受试者需要确定哪个角度较大。为了始终如一地完成此任务,必须将触觉角度的空间特征表示并存储在工作记忆中,然后进行比较和辨别。因此,触觉广告不仅涉及初级处理,而且涉及对触觉感知的高级认知,如工作记忆和注意力。

与各种线向感知测试一样,在触觉广告中,受试者连续呈现一个参考角度和一个比较角度,并被要求指出哪个角度较大,即18、19、20、21。构成角度的线条长度相等,并沿假想的比塞器对称分布。通过对称地更改线条的空间尺寸,可以创建所有类型的凸起平面角度。因此,这种方法的一个关键优点是,被区分的角度具有相似的空间结构。此外,AD 中获得的空间表示比在 GO 中获得的空间表示更具顺序性。然而,AD阈值提供了证据,证明触觉空间敏锐度足以允许对象22之间的空间歧视。此外,角度的触觉空间感知可以从点到线体验,最终形成一个二维平面角度,其中非空间线索可能只起到很小的作用。

AD 阈值被发现随着年龄的增长而增加,这可能是由于触觉 AD 任务中需要高认知负荷。因此,它可以提供认知障碍诊断9,10的监测机制。虽然广告表现受年龄下降的影响,但通过持续训练或类似的触觉任务训练,可以显著改善青少年的广告表现。此外,fMRI研究表明,延迟匹配到样本的触觉角度任务激活了负责工作记忆的某些皮质区域,如后皮层皮层17,24。这些发现表明,触觉角度歧视是衡量触觉空间敏锐性的有希望的指标,涉及高级认知。在这里,触觉AD设备及其使用被详细描述。其他触觉研究人员可以复制AD设备并将其用于研究。

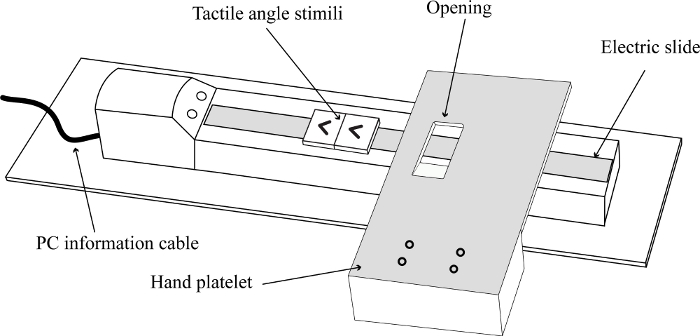

触觉AD设备,或触觉半自动被动手指角刺激器(TSPAS),使用电子滑梯传达一对角度刺激,被动地滑过皮肤(图1)。受试者的手臂舒适地躺着,俯卧在桌面上。右手放在桌子上的手板上,食指板位于盘子开口的正下方。计算机软件可以控制幻灯片,以固定速度移动幻灯片,并向前和向后移动滑动当滑动向前移动时,角度刺激以固定速度从指尖开始被动地滑过皮肤。当滑动向后移动到其启动位置并更改为另一对角度刺激时,主体需要抬起食指,等待命令在打开时再次轻轻放置。因此,设备以可控的速度、稳定的接触持续时间和恒定的间歇间隔呈现触觉角度刺激。受试者口头报告序列号,实验者将其登记为响应,然后进行下一次试验。

图1:TSPAS概述。

设备由四部分组成:1)触觉角度刺激(即参考角和十个比较角度):2) 固定受试者手部并仅使食指与刺激接触的手板:3) 携带触觉刺激的电子滑块:4) 控制电子幻灯片速度和运动距离的个人计算机 (PC) 控制系统。 请点击这里查看此数字的较大版本。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

提出了触觉空间敏锐度的新措施,触觉广告。在此系统中,一对角度被动地滑过主体的固定食指板。AD 结合了 GO 和 TPD 的优势,减少了密集提示的影响和单点的神经峰值脉冲速率。研究表明,随着参考角度和比较角度4之间的角度差异的变化,感性歧视逐渐发生变化。除了年龄效应、训练效果和认知障碍诊断监测外,AD9、10、23、触觉AD是触觉空间敏锐性的宝贵尺度。<sup cl…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

这项工作得到了日本科学促进会KAKENHI赠款JP17J40084、JP18K15339、JP18H05009、JP18H01411、JP18K18835和JP17K18855的支持。我们还感谢实验室的技术人员(田村洋子)帮助我们制作凸起的角度。

Materials

| Acrylic sheet (3 mm) | MonotaRO Co.,Ltd. | 33159874 | Good Material |

| Acrylic sheet (1 mm) | MonotaRO Co.,Ltd. | 45547101 | Good Material |

| EZ limo (easy linear motion motor) | ORIENTAL MOTOR CO., LTD. Made in Japan | EZS3 | Good Motorized Linear Slides |

| Data Editing Software | ORIENTAL MOTOR CO., LTD. Made in Japan | EZED2 | easy to use |

| Operating Manual (Orientalmotor) | ORIENTAL MOTOR CO., LTD. Made in Japan | HL-17151-2 | Good Guidebook |

References

- Smith, A. M., Chapman, C. E., Donati, F., Fortier-Poisson, P., Hayward, V. Perception of simulated local shapes using active and passive touch. Journal of Neurophysiology. 102 (6), 3519-3529 (2009).

- Reuter, E. M., Voelcker-Rehage, C., Vieluf, S., Godde, B. Touch perception throughout working life: Effects of age and expertise. Experimental Brain Research. 216 (2), 287-297 (2012).

- Craig, J. C. Grating orientation as a measure of tactile spatial acuity. Somatosensory and Motor Research. 16 (3), 197-206 (1999).

- Craig, J. C., Johnson, K. O. The two-point threshold: Not a measure of tactile spatial resolution. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 9 (1), 29-32 (2000).

- Tong, J., Mao, O., Goldreich, D. Two-point orientation discrimination versus the traditional two-point test for tactile spatial acuity assessment. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 7, 1-11 (2013).

- Goldreich, D., Wong, M., Peters, R. M., Kanics, I. M. A tactile automated passive-finger stimulator (TAPS). Journal of Visualized Experiments. (28), e1374 (2009).

- Johnson, K. O., Phillips, J. R. Tactile spatial resolution. I. Two-point discrimination, gap detection, grating resolution, and letter recognition. Journal of Neurophysiology. 46 (6), 1177-1191 (1981).

- Legge, G. E., Madison, C., Vaughn, B. N., Cheong, A. M. Y., Miller, J. C. Retention of high tactile acuity throughout the life span in blindness. Perception and Psychophysics. 70 (8), 1471-1488 (2008).

- Yang, J., Ogasa, T., Ohta, Y., Abe, K., Wu, J. Decline of human tactile angle discrimination in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 22 (1), 225-234 (2010).

- Wu, J., Yang, J., Ogasa, T. Raised-angle discrimination under passive finger movement. Perception. 39 (7), 993-1006 (2010).

- Sathian, K., Zangaladze, A. Tactile learning is task specific but transfers between fingers. Perception and Psychophysics. 59 (1), 119-128 (1997).

- Wong, M., Peters, R. M., Goldreich, D. A physical constraint on perceptual learning: tactile spatial acuity improves with training to a limit set by finger size. Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (22), 9345-9352 (2013).

- Trzcinski, N. K., Gomez-Ramirez, M., Hsiao, S. S. Functional consequences of experience-dependent plasticity on tactile perception following perceptual learning. European Journal of Neuroscience. 44 (6), 2375-2386 (2016).

- Essock, E. A., Krebs, W. K., Prather, J. R. Superior Sensitivity for Tactile Stimuli Oriented Proximally-Distally on the Finger: Implications for Mixed Class 1 and Class 2 Anisotropies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 23 (2), 515-527 (1997).

- Gurtubay-Antolin, A., Leon-Cabrera, P., Rodriguez-Fornells, A. Neural evidence of hierarchical cognitive control during Haptic processing: An fMRI study. eNeuro. 5 (6), (2018).

- Yang, J., et al. Tactile priming modulates the activation of the fronto-parietal circuit during tactile angle match and non-match processing: an fMRI study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8, 926 (2014).

- Yu, Y., Yang, J., Ejima, Y., Fukuyama, H., Wu, J. Asymmetric Functional Connectivity of the Contra- and Ipsilateral Secondary Somatosensory Cortex during Tactile Object Recognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 11, (2018).

- Olczak, D., Sukumar, V., Pruszynski, J. A. Edge orientation perception during active touch. Journal of Neurophysiology. 120 (5), 2423-2429 (2018).

- Lederman, S. J., Taylor, M. M. Perception of interpolated position and orientation by vision and active touch. Perception and Psychophysics. 6 (3), 153-159 (1969).

- Peters, R. M., Staibano, P., Goldreich, D. Tactile orientation perception: An ideal observer analysis of human psychophysical performance in relation to macaque area 3b receptive fields. Journal of Neurophysiology. 114 (6), 3076-3096 (2015).

- Bensmaia, S. J., Hsiao, S. S., Denchev, P. V., Killebrew, J. H., Craig, J. C. The tactile perception of stimulus orientation. Somatosensory and Motor Research. 25 (1), 49-59 (2008).

- Morash, V., Pensky, A. E. C., Alfaro, A. U., McKerracher, A. A review of haptic spatial abilities in the blind. Spatial Cognition and Computation. 12 (2-3), 83-95 (2012).

- Wang, W., et al. Tactile angle discriminability improvement: roles of training time intervals and different types of training tasks. Journal of Neurophysiology. 122 (5), 1918-1927 (2019).

- Yang, J., et al. Tactile priming modulates the activation of the fronto-parietal circuit during tactile angle match and non-match processing: an fMRI study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8, 926 (2014).

- Peters, R. M., Hackeman, E., Goldreich, D. Diminutive Digits Discern Delicate Details: Fingertip Size and the Sex Difference in Tactile Spatial Acuity. Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (50), 15756-15761 (2009).

- Sathian, K., Zangaladze, A., Green, J., Vitek, J. L., DeLong, M. R. Tactile spatial acuity and roughness discrimination: Impairments due to aging and Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 49 (1), 168-177 (1997).

- Hoehler, F. K. Logistic equations in the analysis of S-shaped curves. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 5 (3), 367-371 (1995).

- Kuehn, E., Doehler, J., Pleger, B. The influence of vision on tactile Hebbian learning. Scientific Reports. 7 (1), 1-11 (2017).

- Weder, B., Nienhusmeier, M., Keel, A., Leenders, K. L., Ludin, H. P. Somatosensory discrimination of shape: Prediction of success in normal volunteers and parkinsonian patients. Experimental Brain Research. 120 (1), 104-108 (1998).