微殖器的高通量实时成像,测量生长和基因表达中的异质性

Summary

酵母生长表型通过高度平行的延时成像精确测量生长成微殖子的固定细胞。同时,可以监测应力耐受性、蛋白质表达和蛋白质定位,生成综合数据集,研究环境和遗传差异以及同源细胞之间的基因表达异质性如何调节生长。

Abstract

精确测量微生物生长速率的菌株之间和菌株内异质性,对于理解遗传和环境投入对压力耐受性、致病性以及健身的其他关键组成部分至关重要。这份手稿描述了一个基于显微镜的检测,跟踪每个实验大约10 5个糖精微殖子。在多井板中固定酵母的自动延时成像后,通过自定义图像分析软件轻松分析微殖速增长率。对于每个微殖质,也可以监测荧光蛋白的表达和本地化以及急性应激的生存情况。这种测定允许精确估计菌株的平均增长率,以及全面测量克隆种群中生长、基因表达和应力耐受性的异质性。

Introduction

生长表型对酵母健康有至关重要的贡献。自然选择可以有效地区分与增长率不同的血统与相反的有效人口规模,可以超过108个人1。此外,人口内个体增长率的变化是一个进化相关的参数,因为它可以作为生存策略的基础,如押注对冲2,3,4,5,6。因此,能够对生长表型及其分布进行高精度测量的检测对于微生物的研究至关重要。此处描述的微殖器生长测定可以生成每个实验约 105微殖子的个体增长率测量值。因此,这种检测为研究酵母进化遗传学和基因组学提供了强有力的协议。它特别适合测试基因相同的单个细胞种群中的变异性是如何产生、维持和促进种群适应7、8、9、10的。

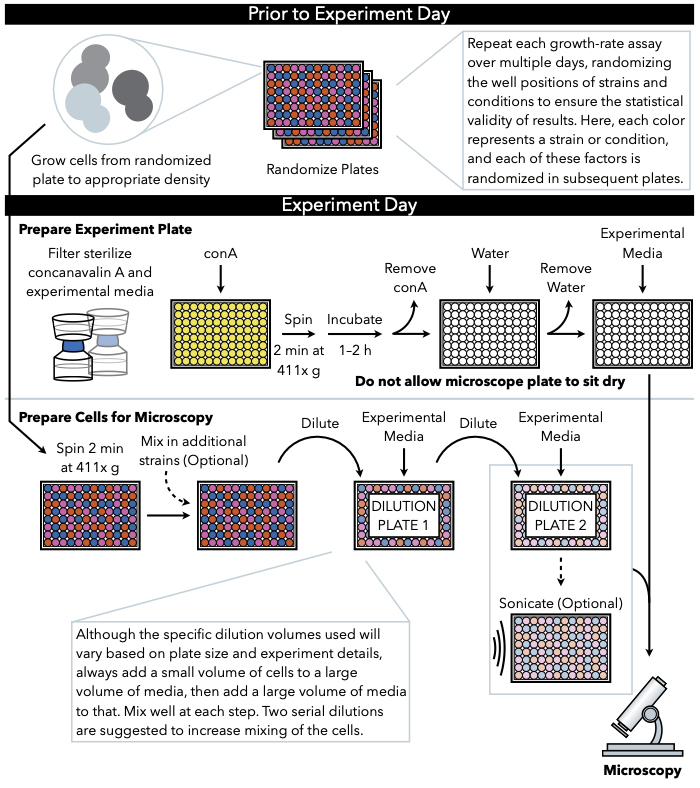

这里描述的方法(图1)使用定期捕获的低放大亮场图像,在96或384井玻璃底板的液体介质中生长的细胞,以跟踪生长成微殖子。细胞粘附在覆盖显微镜板底部的果胶康卡纳瓦林A上,形成二维菌落。由于微殖质生长在单层中,微殖区与7号细胞高度相关。因此,可以通过自定义图像分析软件生成微殖器增长率和滞后时间的准确估计,该软件可跟踪每个微殖器区域的变化速度。此外,实验设置可以监测这些微殖质中表达的荧光标记蛋白质的丰度,甚至亚细胞定位。这种微殖增长测定数据的下游处理可以通过自定义分析或现有的图像分析软件实现,如易处理图像 (PIE)11,这是一种用于强效聚落区域识别的算法,以及来自低放大、亮场图像的高吞吐量增长分析算法,可通过 GitHub12获得。

由于从微殖民增长测定得出的增长率估计来自大量单殖民地测量,因此它们非常准确,标准误差比合理大小的实验本身的估计值小几个数量级。因此,检测不同基因类型、治疗方法或环境条件之间的生长速率差异的功率很高。多井板格式允许在单个实验中比较许多不同的环境和基因型组合。如果菌株构成表达不同的荧光标记,它们可能混合在同一油井中,并通过随后的图像分析进行区分,从而通过允许逐井数据正常化进一步增加功率。

图1:协议的示意图表示。 此协议遵循两个主要步骤,即准备实验板和准备细胞成像。板块的随机化和细胞的生长应在实验日前进行。在稀释过程中,在每一步重复混合细胞在阶梯中必须进行,直到电镀,因此建议首先准备实验板,以便在细胞稀释完成后立即准备电镀。 请单击此处查看此图的更大版本。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

这里描述的协议是一个多功能的检测,允许细胞生长和基因表达同时监测在个别微殖系的水平。结合这两种模式可以产生独特的生物学见解。例如,以前的工作已经使用这个测定显示TSL1基因的表达和同源野生型细胞的微殖体增长率之间的负相关性,同时测量7,10。也可以通过描述的检测来监测荧光标记蛋白质的生长速率和亚细胞定位动力学之间?…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

我们感谢娜奥米·齐夫、萨莎·利维和双李为制定本议定书、大卫·格雷舍姆共享设备和玛丽莎·诺尔在视频制作方面所做的贡献。这项工作得到了国家卫生研究院R35GM118170的支持。

Materials

| General Materials | |||

| 500 mL Bottletop Filter .22 µm PES Sterilizing, Low Protein Binding, w/45mm Neck | Fisher | CLS431154 | used to filter the media |

| BD Falcon*Tissue Culture Plates, microtest u-bottom | Fisher | 08-772-54 | 96-well culture tubes used to freeze cells, pre-grow cells, and dilutions |

| BD Syringes without Needle, 50 mL | Fisher | 13-689-8 | Used to filter the Concanavalin A |

| Costar Sterile Disposable Reagent Reservoirs | Fisher | 07-200-127 | reagent reservoirs used to pipette solutions with multichannel pipette |

| Costar Thermowell Aluminum Sealing Tape | Fisher | 07-200-684 | 96-well plate seal for pre-growth and freezing |

| lint and static free Kimwipes | Fisher | 06-666A | lint and static free wipes to keep microscope plate bottom free of debris and scratches |

| Nalgene Syringe Filters | ThermoFisher Scientific | 199-2020 | 0.2 μm pore size, 25 mm diameter; used to filter concanavalin A solution |

| Media Components | |||

| Minimal chemically defined media (MD; 2% glucose) | alternative microscopy media used for yeast pre-growth and growth during microscopy | ||

| Synthetic Complete Media (SC; 2% glucose) | microscopy media used for yeast pre-growth and growth during microscopy | ||

| Yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YEPD; 2% glucose) medium | cell growth prior to freezing down randomized plates | ||

| Microscopy Materials | |||

| Breathe-Easy sealing membrane | Millipore Sigma | Z380059-1PAK | breathable membranes used to seal plate during microscopy experiment. At this stage breathable membranes are reccomended because they prevent condensation in the wells and allow for better microscopy images |

| Brooks 96-well flat clear glass bottom microscope plate | Dot Scientific | MGB096-1-2-LG-L | microscope plate |

| Concanavalin A from canavalia ensiformis (Jack Bean), lyophilized powder | Millipore Sigma | 45-C2010-1G | Make 5x concanavalin A solution and freeze 5ml of 5x concanavalin A in 50 mL conical tubes at -80 °C |

| Strains Used | |||

| MAH.5, MAH.96, MAH.52, MAH.66, MAH.11, MAH.58, MAH.135, MAH.15, MAH.44, MAH.132 | Haploid mutation accumulation strains in a laboratory background, described in Hall and Joseph 2010 | ||

| EP026.2A-2C | Progeny of the ancestral Hall and Joseph 2010 mutation accumulation strain, transformed with YFR054cΔ::Scw11P::GFP | ||

| Equipment | |||

| Misonix Sonicator S-4000 with 96-pin attachment | Sonicator https://www.labx.com/item/misonix-inc-s-4000-sonicator/4771281 | ||

| Nikon Eclipse Ti-E with Perfect Focus System | Inverted microscope with automated stage and autofocus system |

Referências

- Geiler-Samerotte, K. A., Hashimoto, T., Dion, M. F., Budnik, B. A., Airoldi, E. M., Drummond, D. A. Quantifying condition-dependent intracellular protein levels enables high-precision fitness estimates. PloS one. 8 (9), 75320 (2013).

- Kussell, E., Leibler, S. Phenotypic diversity, population growth, and information in fluctuating environments. Science. 309 (5743), 2075-2078 (2005).

- Thattai, M., van Oudenaarden, A. Stochastic gene expression in fluctuating environments. Genética. 167 (1), 523-530 (2004).

- King, O. D., Masel, J. The evolution of bet-hedging adaptations to rare scenarios. Theoretical population biology. 72 (4), 560-575 (2007).

- Acar, M., Mettetal, J. T., van Oudenaarden, A. Stochastic switching as a survival strategy in fluctuating environments. Nature genetics. 40 (4), 471-475 (2008).

- Avery, S. V. Microbial cell individuality and the underlying sources of heterogeneity. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 4 (8), 577-587 (2006).

- Levy, S. F., Ziv, N., Siegal, M. L. Bet hedging in yeast by heterogeneous, age-correlated expression of a stress protectant. PLoS biology. 10 (5), 1001325 (2012).

- van Dijk, D., et al. Slow-growing cells within isogenic populations have increased RNA polymerase error rates and DNA damage. Nature communications. 6, 7972 (2015).

- Ziv, N., Shuster, B. M., Siegal, M. L., Gresham, D. Resolving the Complex Genetic Basis of Phenotypic Variation and Variability of Cellular Growth. Genética. 206 (3), 1645-1657 (2017).

- Li, S., Giardina, D. M., Siegal, M. L. Control of nongenetic heterogeneity in growth rate and stress tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by cyclic AMP-regulated transcription factors. PLoS genetics. 14 (11), 1007744 (2018).

- Plavskin, Y., Li, S., Ziv, N., Levy, S. F., Siegal, M. L. Robust colony recognition for high-throughput growth analysis from suboptimal low-magnification brightfield micrographs. bioRxiv. , (2018).

- Ziv, N., Siegal, M. L., Gresham, D. Genetic and nongenetic determinants of cell growth variation assessed by high-throughput microscopy. Molecular biology and evolution. 30 (12), 2568-2578 (2013).

- Hall, D. W., Joseph, S. B. A high frequency of beneficial mutations across multiple fitness components in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genética. 185 (4), 1397-1409 (2010).

- Saleemuddin, M., Husain, Q. Concanavalin A: a useful ligand for glycoenzyme immobilization–a review. Enzyme and microbial technology. 13 (4), 290-295 (1991).

- Geiler-Samerotte, K. A., Bauer, C. R., Li, S., Ziv, N., Gresham, D., Siegal, M. L. The details in the distributions: why and how to study phenotypic variability. Current opinion in biotechnology. 24 (4), 752-759 (2013).

- Nakagawa, S., Schielzeth, H. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: a practical guide for biologists. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 85 (4), 935-956 (2010).

- Bolker, J. A. Exemplary and surrogate models: two modes of representation in biology. Perspectives in biology and medicine. 52 (4), 485-499 (2009).