Monitoring the Mechanical Evolution of Tissue During Neural Tube Closure of Chick Embryo

Summary

This protocol was developed to longitudinally monitor the mechanical properties of neural plate tissue during chick embryo neurulation. It is based on the integration of a Brillouin microscope and an on-stage incubation system, enabling live mechanical imaging of neural plate tissue in ex ovo cultured chick embryos.

Abstract

Neural tube closure (NTC) is a critical process during embryonic development. Failure in this process can lead to neural tube defects, causing congenital malformations or even mortality. NTC involves a series of mechanisms on genetic, molecular, and mechanical levels. While mechanical regulation has become an increasingly attractive topic in recent years, it remains largely unexplored due to the lack of suitable technology for conducting mechanical testing of 3D embryonic tissue in situ. In response, we have developed a protocol for quantifying the mechanical properties of chicken embryonic tissue in a non-contact and non-invasive manner. This is achieved by integrating a confocal Brillouin microscope with an on-stage incubation system. To probe tissue mechanics, a pre-cultured embryo is collected and transferred to an on-stage incubator for ex ovo culture. Simultaneously, the mechanical images of the neural plate tissue are acquired by the Brillouin microscope at different time points during development. This protocol includes detailed descriptions of sample preparation, the implementation of Brillouin microscopy experiments, and data post-processing and analysis. By following this protocol, researchers can study the mechanical evolution of embryonic tissue during development longitudinally.

Introduction

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are severe birth defects of the central nervous system caused by failures in neural tube closure (NTC) during embryonic development1. The etiology of NTDs is complex. Studies have shown that NTC involves a sequence of morphogenetic processes, including convergent extension, bending of the neural plate (e.g., apical constriction), elevating the neural fold, and finally adhesion of the neural fold. These processes are regulated by multiple molecular and genetic mechanisms2,3, and any malfunction in these processes may result in NTDs4,5,6. As mounting evidence suggests that mechanical cues also play crucial roles during NTC3,7,8,9,10,11, and relationships have been found between genes and mechanical cues12,13,14, it becomes imperative to investigate the tissue biomechanics during neurulation.

Several techniques have been developed for measuring the mechanical properties of embryonic tissues, including laser ablation (LA)15, tissue dissection and relaxation (TDR)16,17, micropipette aspiration (MA)18, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)-based nanoindentation19, microindenters (MI) and microplates (MP)20, micro rheology (MR) with optical/magnetic tweezers21,22,23, and droplet-based sensors24. Existing methods can measure mechanical properties at spatial resolutions ranging from subcellular to tissue scales. However, most of these methods are invasive because they require contact with the sample (e.g., MA, AFM, MI, and MP), external material injection (e.g., MR and droplet-based sensors), or tissue dissection (e.g., LA and TDR). As a result, it is challenging for existing methods to monitor the mechanical evolution of neural plate tissue in situ25. Recently, reverberant optical coherence elastography has shown promise for non-contact mechanical mapping with high spatial resolution26.

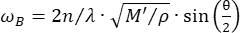

Confocal Brillouin microscopy is an emerging optical modality that enables non-contact quantification of tissue biomechanics with subcellular resolution27,28,29,30. Brillouin microscopy is based on the principle of spontaneous Brillouin light scattering, which is the interaction between the incident laser light and the acoustic wave induced by thermal fluctuations within the material. Consequently, the scattered light experiences a frequency shift, known as the Brillouin shift ωR, following the equation31:

(1)

(1)

Here,  is the refractive index of the material, λ is the wavelength of the incident light, M' is the longitudinal modulus, ρ is the mass density, and θ is the angle between the incident light and the scattered light. For the same type of biological materials, the ratio of refractive index and density

is the refractive index of the material, λ is the wavelength of the incident light, M' is the longitudinal modulus, ρ is the mass density, and θ is the angle between the incident light and the scattered light. For the same type of biological materials, the ratio of refractive index and density  is approximately constant28,32,33,34,35,36. Thus, the Brillouin shift can be directly used to estimate relative mechanical changes in physiological processes. The feasibility of Brillouin microscopy has been validated in various biological samples29,37,38. Recently, time-lapse mechanical imaging of a live chick embryo was demonstrated by combining a Brillouin microscope with an on-stage incubation system39. This protocol provides detailed descriptions of sample preparation, experiment implementation, and data post-processing and analysis. We hope this effort will facilitate the widespread adoption of non-contact Brillouin technology for studying biomechanical regulation in embryo development and birth defects.

is approximately constant28,32,33,34,35,36. Thus, the Brillouin shift can be directly used to estimate relative mechanical changes in physiological processes. The feasibility of Brillouin microscopy has been validated in various biological samples29,37,38. Recently, time-lapse mechanical imaging of a live chick embryo was demonstrated by combining a Brillouin microscope with an on-stage incubation system39. This protocol provides detailed descriptions of sample preparation, experiment implementation, and data post-processing and analysis. We hope this effort will facilitate the widespread adoption of non-contact Brillouin technology for studying biomechanical regulation in embryo development and birth defects.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

The early development of the embryo can be easily affected by external disturbances. Therefore, utmost caution is required during the sample extraction and transfer. One potential issue is the detachment of the embryo from the filter paper, which can lead to the shrinking of the vitelline membrane and result in a tilted artifact of the neural plate in Brillouin imaging. Furthermore, this shrinking may halt the development of the embryo. Attention should be paid to several critical steps to prevent detachment. First, in s…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (K25HD097288, R21HD112663).

Materials

| 100 mm Petri dish | Fisherbrand | FB0875713 | |

| 2D motorized stage | Prior Scientific | H117E2 | |

| 35 mm Petri dish | World Precision Instruments | FD35-100 | |

| Brillouin Microscope with on-stage incubator | N/A | N/A | This is a custom-built Brillouin Microscope system based on Ref. 30 |

| Chicken eggs | University of Connecticut | N/A | |

| CMOS camera | Thorlabs | CS2100M-USB | |

| EMCCD camera | Andor | iXon | |

| Ethanol | Decon Laboratories, Inc. | #2701 | |

| Filter paper | Whatman | 1004-070 | |

| Incubator for in ovo culture | GQF Manufacturing Company Inc. | GQF 1502 | |

| Ring | Thorlabs | SM1RR | |

| Microscope body | Olympus | IX73 | |

| NaCl | Sigma-Aldrich | S9888 | |

| On-stage incubator | Oko labs | OKO-H301-PRIOR-H117 | |

| Parafilm | Bemis | PM-996 | |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Gibco | 15070-063 | |

| Pipettes | Fisherbrand | 13-711-6M | |

| Scissors | Artman instruments | N/A | 3pc Micro Scissors 5 |

| Syringe | BD | 305482 | |

| Tissue paper | Kimwipes | N/A | |

| Tube | Corning | 430052 | |

| Tweezers | DR Instruments | N/A | Microdissection Forceps Set |

Referências

- Greene, N. D. E., Copp, A. J. Neural tube defects. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 37 (1), 221-242 (2014).

- Suzuki, M., Morita, H., Ueno, N. Molecular mechanisms of cell shape changes that contribute to vertebrate neural tube closure. Development, Growth & Differentiation. 54 (3), 266-276 (2012).

- Nikolopoulou, E., Galea, G. L., Rolo, A., Greene, N. D. E., Copp, A. J. Neural tube closure: Cellular, molecular and biomechanical mechanisms. Development. 144 (4), 552-566 (2017).

- Juriloff, D. M., Harris, M. J. Mouse models for neural tube closure defects. Human Molecular Genetics. 9 (6), 993-1000 (2000).

- Copp, A. J., Greene, N. D. E. Genetics and development of neural tube defects. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 220 (2), 217-230 (2010).

- Wang, M., De Marco, P., Capra, V., Kibar, Z. Update on the role of the non-canonical wnt/planar cell polarity pathway in neural tube defects. Cells. 8 (10), 1198 (2019).

- Galea, G. L., et al. Biomechanical coupling facilitates spinal neural tube closure in mouse embryos. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (26), E5177-E5186 (2017).

- Moon, L. D., Xiong, F. Mechanics of neural tube morphogenesis. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 130, 56-69 (2022).

- Christodoulou, N., Skourides, P. A. Distinct spatiotemporal contribution of morphogenetic events and mechanical tissue coupling during xenopus neural tube closure. Development. 149 (13), (2022).

- De Goederen, V., Vetter, R., Mcdole, K., Iber, D. Hinge point emergence in mammalian spinal neurulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (20), 2117075119 (2022).

- Christodoulou, N., Skourides, P. A. Somitic mesoderm morphogenesis is necessary for neural tube closure during xenopus development. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 10, 1091629 (2023).

- Nikolopoulou, E., et al. Spinal neural tube closure depends on regulation of surface ectoderm identity and biomechanics by grhl2. Nature Communications. 10 (1), 2487 (2019).

- Nychyk, O., et al. Vangl2-environment interaction causes severe neural tube defects, without abnormal neuroepithelial convergent extension. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 15 (1), 049194 (2022).

- Li, B., Brusman, L., Dahlka, J., Niswander, L. A. Tmem132a ensures mouse caudal neural tube closure and regulates integrin-based mesodermal migration. Development. 149 (17), (2022).

- Zulueta-Coarasa, T., Fernandez-Gonzalez, R. Laser ablation to investigate cell and tissue mechanics in vivo. Integrative Mechanobiology: Micro-and Nano Techniques in Cell Mechanobiology. , 128-147 (2015).

- Wiebe, C., Brodland, G. W. Tensile properties of embryonic epithelia measured using a novel instrument. Journal of Biomechanics. 38 (10), 2087-2094 (2005).

- Luu, O., David, R., Ninomiya, H., Winklbauer, R. Large-scale mechanical properties of xenopus embryonic epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (10), 4000-4005 (2011).

- Maître, J. L., Niwayama, R., Turlier, H., Nédélec, F., Hiiragi, T. Pulsatile cell-autonomous contractility drives compaction in the mouse embryo. Nature Cell Biology. 17 (7), 849-855 (2015).

- Krieg, M., et al. Tensile forces govern germ-layer organization in zebrafish. Nature Cell Biology. 10 (4), 429-436 (2008).

- Zamir, E. A., Srinivasan, V., Perucchio, R., Taber, L. A. Mechanical asymmetry in the embryonic chick heart during looping. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 31, 1327-1336 (2003).

- Bambardekar, K., Clément, R., Blanc, O., Chardès, C., Lenne, P. F. Direct laser manipulation reveals the mechanics of cell contacts in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (5), 1416-1421 (2015).

- Savin, T., et al. On the growth and form of the gut. Nature. 476 (7358), 57-62 (2011).

- Almonacid, M., et al. Active diffusion positions the nucleus in mouse oocytes. Nature Cell Biology. 17 (4), 470-479 (2015).

- Campàs, O., et al. Quantifying cell-generated mechanical forces within living embryonic tissues. Nature Methods. 11 (2), 183-189 (2014).

- Campàs, O. A toolbox to explore the mechanics of living embryonic tissues. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 55, 119-130 (2016).

- Christian, Z. D., et al. High-resolution 3D biomechanical mapping of embryos with reverberant optical coherence elastography (Rev-OCE). Proceedings of SPIE. , 123670 (2023).

- Scarcelli, G., Yun, S. H. J. N. P. Confocal brillouin microscopy for three-dimensional mechanical imaging. Nature Photonics. 1 (1), 39-43 (2008).

- Scarcelli, G., et al. Noncontact three-dimensional mapping of intracellular hydromechanical properties by brillouin microscopy. Nature Methods. 12 (12), 1132-1134 (2015).

- Prevedel, R., Diz-Muñoz, A., Ruocco, G., Antonacci, G. Brillouin microscopy: An emerging tool for mechanobiology. Nature Methods. 16 (10), 969-977 (2019).

- Zhang, J., Scarcelli, G. Mapping mechanical properties of biological materials via an add-on brillouin module to confocal microscopes. Nature Protocols. 16 (2), 1251-1275 (2021).

- Boyd, R. W. . Nonlinear optics. , (2020).

- Scarcelli, G., Kim, P., Yun, S. H. In vivo measurement of age-related stiffening in the crystalline lens by brillouin optical microscopy. Biophysical Journal. 101 (6), 1539-1545 (2011).

- Scarcelli, G., Pineda, R., Yun, S. H. Brillouin optical microscopy for corneal biomechanics. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 53 (1), 185-190 (2012).

- Antonacci, G., Braakman, S. Biomechanics of subcellular structures by non-invasive brillouin microscopy. Scientific Reports. 6 (1), 37217 (2016).

- Zhang, J., et al. Tissue biomechanics during cranial neural tube closure measured by brillouin microscopy and optical coherence tomography. Birth Defects Research. 111 (14), 991-998 (2019).

- Zhang, J., et al. Nuclear mechanics within intact cells is regulated by cytoskeletal network and internal nanostructures. Small. 16 (18), 1907688 (2020).

- Elsayad, K., Polakova, S., Gregan, J. Probing mechanical properties in biology using brillouin microscopy. Trends in Cell Biology. 29 (8), 608-611 (2019).

- Poon, C., Chou, J., Cortie, M., Kabakova, I. Brillouin imaging for studies of micromechanics in biology and biomedicine: From current state-of-the-art to future clinical translation. Journal of Physics: Photonics. 3 (1), 012002 (2020).

- Handler, C., Scarcelli, G., Zhang, J. Time-lapse mechanical imaging of neural tube closure in live embryo using brillouin microscopy. Scientific Reports. 13 (1), 263 (2023).

- Chapman, S. C., Collignon, J., Schoenwolf, G. C., Lumsden, A. Improved method for chick whole-embryo culture using a filter paper carrier. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 220 (3), 284-289 (2001).

- Schmitz, M., Nelemans, B. K. A., Smit, T. H. A submerged filter paper sandwich for long-term ex ovo time-lapse imaging of early chick embryos. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (118), e54636 (2016).

- Nys, Y., Guyot, N., Nys, Y., Bain, M., VanImmerseel, F. . Improving the safety and quality of eggs and egg products, vol 1: Egg chemistry, production and consumption. , 83-132 (2011).

- Berghaus, K. V., Yun, S. H., Scarcelli, G. High speed sub-ghz spectrometer for brillouin scattering analysis. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (106), e53468 (2015).

- Hamburger, V., Hamilton, H. L. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. Journal of Morphology. 88 (1), 49-92 (1951).

- Schlüßler, R., et al. Mechanical mapping of spinal cord growth and repair in living zebrafish larvae by brillouin imaging. Biophysical Journal. 115 (5), 911-923 (2018).

- Williams, R. M., Sauka-Spengler, T. Ex ovo electroporation of early chicken embryos. STAR Protocols. 2 (2), 100424 (2021).

- Chapman, S. C., Collignon, J., Schoenwolf, G. C., Lumsden, A. Improved method for chick whole-embryo culture using a filter paper carrier. Developmental Dynamics. 220 (3), 284-289 (2001).

- Edrei, E., Scarcelli, G. Adaptive optics in spectroscopy and densely labeled-fluorescence applications. Optics Express. 26 (26), 33865-33877 (2018).