12.11:

אוסמוזיס ולחץ אוסמוטי של תמיסות

12.11:

אוסמוזיס ולחץ אוסמוטי של תמיסות

A number of natural and synthetic materials exhibit selective permeation, meaning that only molecules or ions of a certain size, shape, polarity, charge, and so forth, are capable of passing through (permeating) the material. Biological cell membranes provide elegant examples of selective permeation in nature, while dialysis tubing used to remove metabolic wastes from blood is a more simplistic technological example. Regardless of how they may be fabricated, these materials are generally referred to as semipermeable membranes.

Consider a U-shaped apparatus, in which samples of pure solvent and a solution are separated by a membrane that only solvent molecules may permeate. Solvent molecules will diffuse across the membrane in both directions. Since the concentration of solvent is greater in the pure solvent than the solution, these molecules will diffuse from the solvent side of the membrane to the solution side at a faster rate than they will in the reverse direction. The result is a net transfer of solvent molecules from the pure solvent to the solution. Diffusion-driven transfer of solvent molecules through a semipermeable membrane is a process known as osmosis.

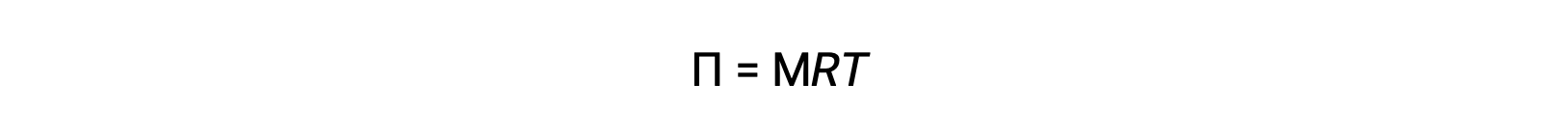

When osmosis is carried out in an apparatus described above, the volume of the solution increases as it becomes diluted by the accumulation of solvent. This causes the level of the solution to rise, increasing its hydrostatic pressure (due to the weight of the column of the solution in the tube) and resulting in a faster transfer of solvent molecules back to the pure solvent side. When the pressure reaches a value that yields a reverse solvent transfer rate equal to the osmosis rate, bulk transfer of solvent ceases. This pressure is called the osmotic pressure (Π) of the solution. The osmotic pressure of a dilute solution is related to its solute molarity, M, and absolute temperature, T, according to the equation

where R is the universal gas constant.

If a solution is placed in such an apparatus, applying pressure greater than the osmotic pressure of the solution reverses the osmosis and pushes solvent molecules from the solution into the pure solvent. This technique of reverse osmosis is used for large-scale desalination of seawater and on smaller scales to produce high-purity tap water for drinking.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 11.4: Colligative Properties.

Suggested Reading

- Goodhead, Lauren K., and Frances M. MacMillan. "Measuring osmosis and hemolysis of red blood cells." Advances in physiology education 41, no. 2 (2017): 298-305.

- Garbarini, G. R., R. F. Eaton, T. K. Kwei, and A. V. Tobolsb. "Diffusion and reverse osmosis through polymer membranes." Journal of Chemical Education 48, no. 4 (1971): 226.

- Hitchcock, David I. "Osmotic pressure and molecular weight." Journal of Chemical Education 28, no. 9 (1951): 478.