19.3:

核の安定性

19.3:

核の安定性

陽子と中性子は核子と呼ばれ、原子核を構成しています。原子核の半径は約10−15メートルで、原子全体の半径が約10−10メートルであることと比較すると、非常に小さいです。原子核は、1立方センチメートルあたり平均1.8 ×1014グラムと、物質に比べて非常に密度が高いです。もし、地球の密度が原子核の平均密度と同じであれば、地球の半径は約200メートルしかないことになります。

正電荷を帯びた陽子は、短い距離では互いに強く反発するため、原子核という非常に小さな体積の中で正電荷を帯びた陽子をつなぎとめるには、非常に強い引力が必要となります。原子核をつなぎとめる引力が「強い核力」です。この力は、陽子の間、中性子の間、陽子と中性子の間に働きます。この力は、正電荷を帯びた原子核の周りに負電荷を帯びた電子を保持する静電力とは大きく異なります。10−15メートル以下の距離や原子核内では、強い核力は陽子間の静電的な反発よりもはるかに強く、それ以上の距離や原子核外では基本的に存在しません。

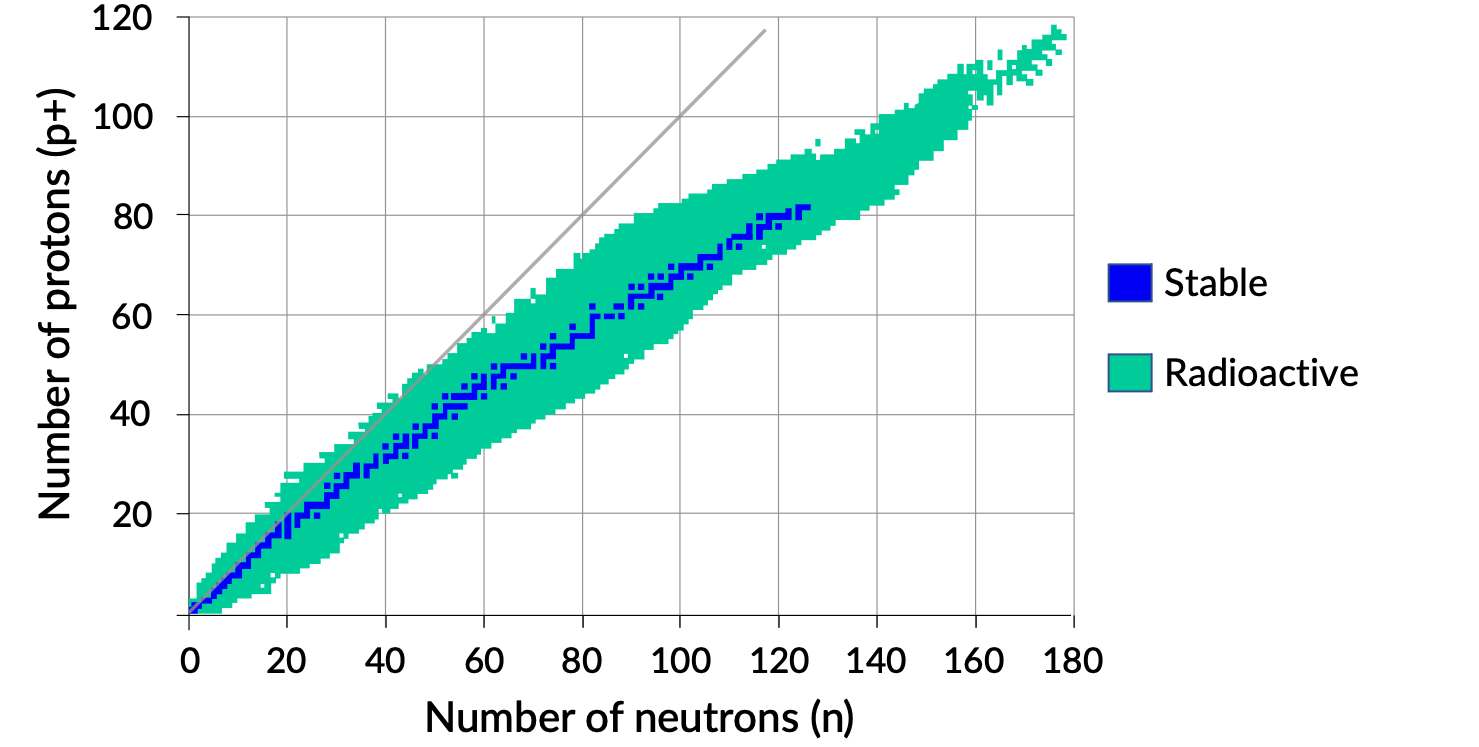

安定した原子核の中性子の数と陽子の数をプロットすると、安定同位体は狭い範囲に収まることがわかります。この領域は、安定帯(安定のベルト、ゾーン、バレーとも呼ばれる)と呼ばれています。Figure. 1の直線は、陽子と中性子の比(n:p比)が1:1の原子核を表しています。なお、軽い安定核は、一般に陽子と中性子の数が同じです。例えば、窒素-14は陽子が7個、中性子が7個です。一方、重い安定した原子核は、陽子よりも中性子の数が次第に多くなります。例えば、安定核種の鉄-56は、中性子が30個、陽子が26個で、n:p比が1.15であるのに対し、安定核種の鉛-207は、中性子が125個、陽子が82個で、n:p比が1.52です。これは、原子核が大きくなると陽子の反発が大きくなり、この静電反発を克服して原子核を結合させるための強い力を補うために、より多くの中性子を必要とするためです。

Figure 1. 原子核の安定帯

安定帯の外側にある原子核は不安定であり、放射性を示します。すなわち、安定帯にある、あるいは安定帯に近い他の原子核に自然に変化する(崩壊する)。このような核崩壊反応により、不安定な核種(放射性核種)が別の核種(多くの場合、より安定した核種)に変化します。

核の安定性と構造の関係については、いくつかの経験則があります。

陽子、中性子、またはその両方の数が偶数の原子核は安定しやすいです。マジックナンバーと呼ばれる特定の数の核子を持つ原子核は、核崩壊に対して安定しています。これらの数の陽子または中性子(2、8、20、28、50、82、126)は、原子核の中で完全な殻を構成しています。これは、希ガスの安定した電子殻と似た概念です。陽子と中性子の両方がマジックナンバーである原子核は “doubly magic”と呼ばれ、特に安定しています。

原子番号が82以上の原子核は放射性物質です。原子番号83のビスマス-209は、非常に長い間安定しているため、放射性物質ではないかのように扱うことができます。放射性物質ではありますが、半減期が放射性核種の中では非常に長いのが特徴です。

自然界に存在する重元素の放射性同位体は連鎖崩壊を起こし、1つの連鎖に含まれるすべての種が放射性ファミリー(放射性崩壊系列)を構成しています。周期表の天然放射性元素のほとんどは、これら3つの系列に含まれています。これらは、ウラン系列、アクチノイド系列、トリウム系列です。ネプツニウム系列は4つ目の系列で、半減期が短いため、地球上では重要ではありません。

上記の文章は以下から引用しました。 Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 21.1: Nuclear Structure and Stability.