习惯: 学习婴儿才可以谈

English

Share

Overview

资料来源: 实验室的尼古拉 Noles、 朱迪思 · Danovitch 和卡拉 Cashon — — 路易斯维尔大学

婴儿是信息的最纯净的来源关于人类思维和学习,因为他们已经很少的生活经验。因此,研究人员感兴趣从婴儿,收集数据,但是作为实验研究的参与者,他们是一个具有挑战性的小组来研究。与不同的大龄儿童和成人,婴幼儿都无法可靠地讲、 理解语音,或甚至移动和控制自己的身体。吃饭、 睡觉,和四处张望是婴儿可以可靠地执行的唯一活动。鉴于这些限制,研究者开发了巧妙的方法探索婴儿的想法。最受欢迎的方法之一,利用注意特征的叫适应。

成人一样,婴儿更喜欢关注新的和有趣的事情。如果他们留在相同的环境,随着时间的推移他们变得习惯于周围的环境,较少注意到他们。这个过程被称为成瘾。然而,新的东西的那一刻发生,婴儿都在等待准备再次集中注意力。注意以下习惯称为去习惯这 reengagement。科学家可以使用这些特性的变化作为一种工具在注意学习思维和学习的婴幼儿。这种方法涉及最初呈现给婴儿的刺激,直到他们习惯,然后与不同种类的刺激来看看是否他们 dishabituate,即注意到改变他们提出。研究人员通过仔细选择刺激婴儿所示,可以学到很多关于婴儿如何思考和学习。

本实验演示如何使用习惯研究婴儿形状歧视。

Procedure

Results

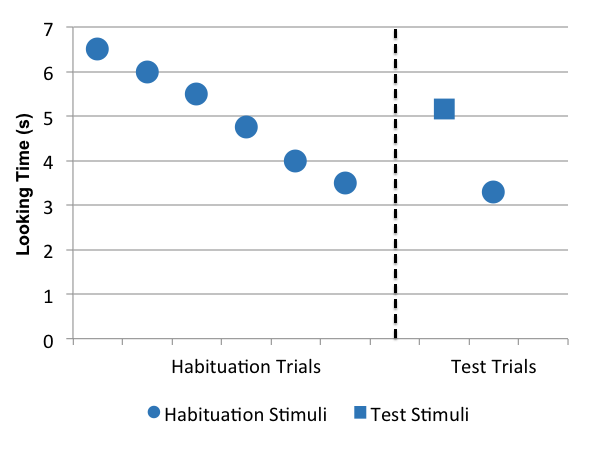

In order to have enough power to see significant results, researchers need to test at least 16 infants, not including infants dropped from the study for failing to habituate, fussiness, falling asleep, parent interference, etc.. Infants who have habituated are expected to show low levels of looking when shown the habituation stimulus during test. If infants look longer at the novel test stimulus in comparison to the habituation test stimulus after they have habituated (Figure 1), researchers would conclude that infants discriminated the stimuli. Good test stimuli are well controlled and as similar to habituation trials as possible, with the exception of the key variable being manipulated, in this case shape.

Figure 1: Average looking time across infants during habituation and test phases. The habituation stimulus is identical to the items seen during habituation, resulting in very low looking times. Infants dishabituate, or look longer, at the novel test stimulus in comparison to the habituation stimulus, if they notice the different shape.

Applications and Summary

Other senses can also be tested using these same methods. For example, it is possible to measure infants’ habituation and dishabituation to auditory stimuli using pacifiers designed to measure the rate and strength of their sucking. Attentive babies suck more often and harder than babies who are habituated, so the same methods can be applied using different approaches.

Habituation methods are both powerful and limited in specific ways. When infants dishabituate, experimenters can conclude that they noticed some difference between familiar and novel test items, but it takes careful experimental design to draw conclusions from work with infants. Working with infants also creates special challenges. Most scientists do not have to worry about their participants needing a nap or diaper change during their study. However, habituation methods can be a powerful tool for studying participants unable to communicate. This approach is especially valuable to developmental scientists who are interested in studying abilities that humans are born with, as well as those that develop with very few life experiences.

Habituation methods are also used to study much more complex topics, such as the development of concepts of race, gender, and fairness. For example, by presenting infants with faces belonging to different racial groups, researchers discovered that 3-month-old babies identify new and old faces independent of race.1 However, between 6- and 9-months of age, infants undergo perceptual narrowing, after which they are more adept at recognizing individuals in their own racial group, but they find it difficult to discriminate between faces belonging to other racial groups. Thus, habituation methods represent a powerful tool for studying infant cognition and human development.

References

- Kelly, D. J., Quinn, P. C., Slater, A. M., Lee, K., Ge, L., & Pascalis, O. The other-race effect develops during infancy: Evidence of perceptual narrowing. Psychological Science. 18 (12), 1084-1089 (2007).

Transcript

To explore the early stages of conceptual development—when infants are unable to reliably speak, understand speech, or precisely control movements—researchers have established clever techniques that use habituation methods.

Like adults, infants prefer to pay attention to new and interesting things. If left in the same environment, over time they become accustomed to their surroundings and pay less attention to them. This process is called habituation.

However, the moment something new happens, infants are ready to pay attention again. Such reengagement of attention following habituation is referred to as dishabituation.

Scientists can use these characteristic changes in attention as a tool for studying the thinking and learning processes of young infants.

This video demonstrates how to design and execute an infant habituation paradigm, as well as how to analyze and interpret results for investigating their shape discrimination.

In this experiment, six-month-old infants are exposed to different shape stimuli in two phases, thus using a within-subjects design to compare whether or not habituation towards one shape persists and dishabituation occurs with the presentation of a new shape.

In the initial phase, infants are shown stimuli on a video monitor: first an “attention-getter”—an image that moves and makes sounds to direct their attention—followed by a shape stimulus, such as a blue circle.

In this case, the dependent variable measured is the time that the infants spend looking at the shape stimulus. Because they (typically) spend more time looking during the first three trials, these times are averaged as the baseline time.

The habituation phase is continued until the infant’s time spent looking at the stimulus is 50% or less than baseline for three sequential trials. Thus, the number of trials required to reach habituation may vary between babies.

Once habituation is reached, the test phase is started, and only two trials are presented in a counterbalanced manner; that is, infants are again shown the attention-getter to start, after which, half will first see the familiar blue circle that was shown during the habituation phase, and the other half will start with a novel blue square.

When babies are presented with the familiar shape, they are predicted to remain habituated—their looking times will remain relatively unchanged. However, during the presentation of a novel stimulus, babies are expected to dishabituate—they will re-engage their attention and look longer when they detect a change.

Before the infant and parent arrive, prepare a quiet testing room by placing a comfortable chair in front of a large monitor equipped with a video camera.

Upon arrival, greet the infant and parent. Instruct the parent to hold their infant and remain as quiet as possible while looking at a point just below the center of the screen.

From another room, monitor the infant using the video feed from the camera. Initiate the software that controls stimuli presentation and records looking times. Note that in this view, you can only see whether the infant is looking at or away from the monitor and not what appears on their screen.

When the infant is looking at the monitor, press the ‘5’ key, which is assigned to log looking times. Notice that the program first displays a stimulus on the infant’s screen to capture their attention, followed by the blue circle.

As soon as the infant looks away for more than 1 s, release the timing key—automatically ending the trial—or, when they look at the screen for the maximum duration of 20 s.

After three trials, examine the baseline time—the calculated average looking time across these trials. Repeat trials until the infant reaches criterion for habituation. Remember that the number of trials required might vary across infants.

Once criterion has been reached, automatically proceed to the test phase that now includes a novel blue square in one of the two trials—counterbalanced across infants.

Following the test phase, end the session by thanking the parent and infant for participating.

To analyze the results, graph the mean looking times for all of the infants who met criterion during the habituation phase, and for the test phase, by stimulus shape—the familiar blue circle and novel blue square.

Over the course of the habituation trials, the average looking time decreased to be approximately half as long in duration.

When infants saw a new stimulus during the test phase—the blue square—they showed the hallmark signs of dishabituation. Notably, their looking times increased relative to the familiar test stimulus, suggesting that they noticed the new shape.

Now that you are familiar with the habituation methods used as a tool designed to study infant shape discrimination, let’s look at other ways that developmental psychologists use the paradigm.

Researchers can examine other sensory modalities. For example, it is possible to measure infants’ habituation and dishabituation to auditory stimuli using specially designed pacifiers that gage the rate and strength of their sucking. Attentive babies suck more often and harder than babies who are habituated.

Habituation is also used to study more complex topics, such as the development of concepts of race, gender, and fairness. For instance, by presenting infants with faces belonging to different racial groups, researchers discovered that 3-month-old babies identified new and old faces independent of race.

However, between 6- and 9-months of age, infants undergo perceptual narrowing, making them more adept at recognizing individuals in their own racial group, and less able to discriminate between faces belonging to other racial groups.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s introduction to examining habituation methods in infants. Now you should have a good understanding of how to setup and perform the experiment, as well as analyze and assess the results.

Thanks for watching!