Analisi cinematica di divisione cellulare e di espansione: Quantificare la base cellulare della crescita e dello sviluppo di campionamento zone in<em> Zea mays</em> Foglie

Summary

Quantifying cell division and expansion is of crucial importance to the understanding of whole-plant growth. Here, we present a protocol to calculate cellular parameters determining maize leaf growth rates and highlight the use of these data for investigating molecular growth regulatory mechanisms by directing developmental stage-specific sampling strategies.

Abstract

Growth analyses are often used in plant science to investigate contrasting genotypes and the effect of environmental conditions. The cellular aspect of these analyses is of crucial importance, because growth is driven by cell division and cell elongation. Kinematic analysis represents a methodology to quantify these two processes. Moreover, this technique is easy to use in non-specialized laboratories. Here, we present a protocol for performing a kinematic analysis in monocotyledonous maize (Zea mays) leaves. Two aspects are presented: (1) the quantification of cell division and expansion parameters, and (2) the determination of the location of the developmental zones. This could serve as a basis for sampling design and/or could be useful for data interpretation of biochemical and molecular measurements with high spatial resolution in the leaf growth zone. The growth zone of maize leaves is harvested during steady-state growth. Individual leaves are used for meristem length determination using a DAPI stain and cell-length profiles using DIC microscopy. The protocol is suited for emerged monocotyledonous leaves harvested during steady-state growth, with growth zones spanning at least several centimeters. To improve the understanding of plant growth regulation, data on growth and molecular studies must be combined. Therefore, an important advantage of kinematic analysis is the possibility to correlate changes at the molecular level to well-defined stages of cellular development. Furthermore, it allows for a more focused sampling of specified developmental stages, which is useful in case of limited budget or time.

Introduction

analisi della crescita dipende da una serie di strumenti che vengono comunemente utilizzati dagli scienziati vegetali per descrivere genotipo determinato differenze di crescita e / o risposte fenotipiche a fattori ambientali. Essi comprendono dimensione e peso misurazioni di tutta la pianta o di un organo e calcoli dei tassi di crescita per esplorare i meccanismi alla base della crescita. Crescita degli organi è determinata dalla divisione cellulare e l'espansione a livello cellulare. Pertanto, compresa la quantificazione di questi due processi in crescita analizza è la chiave per comprendere le differenze nella crescita dell'intero organo-1. Pertanto, è fondamentale disporre di un metodo adeguato per determinare i parametri di crescita cellulare che è relativamente facile da usare da laboratori non specializzati.

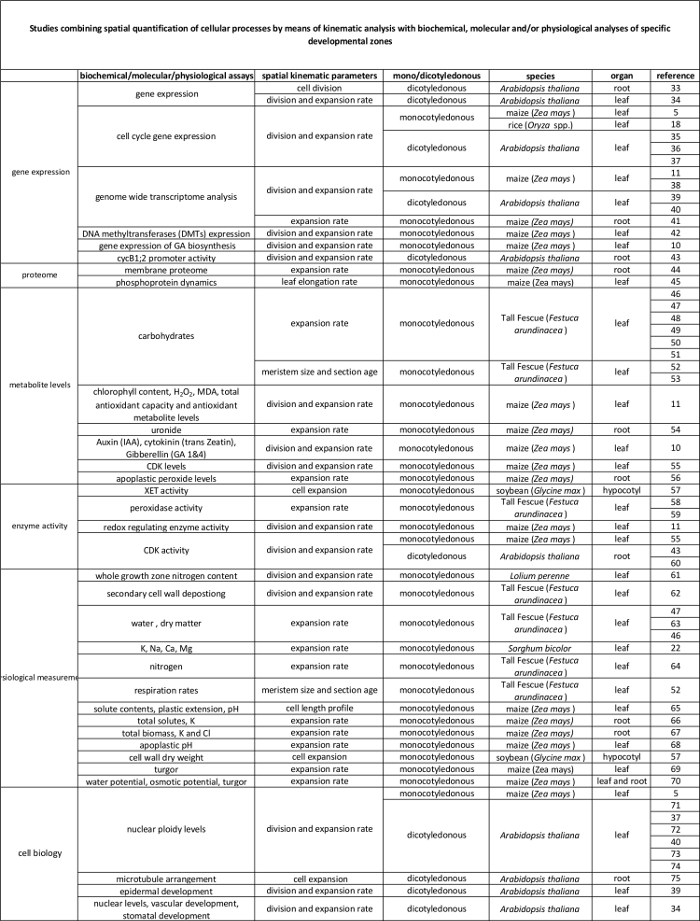

Analisi cinematica è già stato stabilito come un approccio che fornisce un quadro potente per lo sviluppo di modelli di crescita di organi 2. La tecnica è stata ottimizzata per sistemi lineari,come radici Arabidopsis thaliana e foglie monocotiledoni, ma anche per i sistemi non lineari, come foglie dicotiledoni 3. Al giorno d'oggi, questa metodologia è sempre più utilizzato per studiare come genetici, ormonali, dello sviluppo e fattori ambientali influenzano la divisione cellulare e di espansione in vari organi (Tabella 1). Inoltre, fornisce anche un quadro di collegare processi cellulari ai loro regolamenti biochimici, molecolari e fisiologici sottostanti (Tabella 2), anche se le limitazioni possono essere imposte in base alle dimensioni degli organi e l'organizzazione spaziale per tecniche che richiedono una maggiore quantità di materiale vegetale (ad esempio, di metaboliti misurazioni, proteomica, etc.).

Foglie monocotyledonous, come il mais (Zea mays) foglie, rappresentano sistemi lineari in cui le cellule si spostano dalla base della foglia verso la punta, sequenzialmente passando attraverso il meristema e l'allungamento zona per raggiungere la maturitàzona. Questo lo rende un sistema modello ideale per studi quantitativi dei modelli spaziali di crescita del 4. Inoltre, foglie di mais hanno zone di forte crescita (meristema e zona di allungamento che abbracciano diversi centimetri 5) e forniscono possibilità per gli studi ad altri livelli organizzativi. Questo permette la ricerca dei (presunti) meccanismi regolatori che controllano la divisione cellulare e di espansione, quantificato da analisi cinematica attraverso una serie di tecniche molecolari, misurazioni fisiologiche, e approcci di biologia cellulare (Tabella 2).

Qui, forniamo un protocollo per l'esecuzione di una analisi cinematica in foglie monocot. In primo luogo, spieghiamo come condurre una corretta analisi sia di divisione cellulare e l'allungamento delle cellule in funzione della posizione lungo l'asse foglia e come calcolare i parametri cinematici. In secondo luogo, mostriamo anche come questo può essere utilizzato come base per il disegno di campionamento. Qui, discutiamo due casi: ad alta risoluzione di campionamento di und focalizzata campionamento, consentendo una migliore interpretazione dei dati e il risparmio di tempo / denaro, rispettivamente.

Tabella 1. Panoramica di cinematica analizza i metodi per la quantificazione della divisione cellulare e di espansione in vari organi.

| organo | riferimento |

| foglie monocotiledoni | 16, 20, 21, 22 |

| apici radicali | 2, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 |

| foglie dicotiledoni | 21, 30, 31 |

| sparare meristema apicale | 32 |

Tabella 1. Panoramica di cinematica analizza i metodi per la quantificazione della divisione cellulare e di espansione in vari organi.

<p class="jove_content" fo:keep-together.within-page = "1">

Tabella 2. Collegamento tra processi cellulari quantificati dall'analisi cinematica per la loro regolamentazione a livello molecolare. I riferimenti ai vari studi che collegano la quantificazione dei processi cellulari ai risultati di saggi biochimici e molecolari di varie specie e organi. Endotransglucosylase Xyloglucan (XET), malondialdeide (MDA), chinasi ciclina-dipendenti (CDK). Clicca qui per vedere una versione più grande di questa tabella.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

Una completa analisi cinematica sulle foglie di mais consente la determinazione della base cellulare della crescita delle foglie e consente la progettazione di strategie di campionamento efficienti. Anche se il protocollo è relativamente semplice, una certa cautela è raccomandata nei seguenti passaggi critici: (1) E 'importante staccare le foglie più giovani chiusi (punto 2.3) senza danneggiare il meristema, dal momento che la determinazione lunghezza meristema (fase 3) richiede la completa meristem di essere pre…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Questo lavoro è stato sostenuto da una borsa di dottorato di ricerca presso l'Università di Anversa a VA; una borsa di dottorato di ricerca dal fiammingo Science Foundation (FWO, 11ZI916N) di KS; sovvenzioni per progetti dal FWO (G0D0514N); una borsa di attività di ricerca concertata (GOA) la ricerca, "Un Systems Biology Approach di Leaf morfogenesi" dal Consiglio di ricerca dell'Università di Anversa; e il Interuniversitario di attrazione Poli (IUAP VII / 29, MARS), "mais e Arabidopsis radice e sparare crescita" dal Science Policy Ufficio federale belga (BELSPO) per GTSB Han Asard, Bulelani L. Sizani e Hamada AbdElgawad tutti hanno contribuito al video .

Materials

| Pots | Any | Any | We use pots with the following measueres, but can be different depending on the treatment/study : bottom diameter: 11cm, opening diameter: 15 cm, height: 12 cm. We grow one maize plant per pot. |

| Planting substrate | Any | Any | We use potting medium (Jiffy, The Netherlands), but other substrates can be used, depending on treatment/study. |

| Ruler | Any | Any | An extension ruler that covers at least 1,5 meters is needed to measure the final leaf length of the plants. |

| Seeds | Any | NA | Seeds can be ordered from a breeder. |

| Scalpel | Any | Any | The scalpel is used during leaf harvesting to detach the leaf of interest from its surrounding leaves and right after harvesting to cut a proper sample for cell length and meristem length measurements. |

| 15 ml falcon tubes | Any | Any | The 15 ml falcon tubes are used for storing samples used for cell length measurements during sample clearing with absolute ethanol and lactic acid. |

| Eppendorf tubes | Any | Any | The eppendorf tubes are used for storing samples used for meristem length measurements in ethanol:acetic acid 3:1 (v:v) solution. |

| Gloves | Any | Any | Latex gloves, which protect against corrosive reagents. |

| Acetic acid | Any | Any | CAUTION: Corrosive to metals, category 1 Skin corrosion, categories 1A,1B,1C Serious eye damage, category 1; Flammable liquids, categories 1,2,3 |

| Absolute ethanol | Any | Any | CAUTION: Hazardous in case of skin contact (irritant), of eye contact (irritant), of inhalation. Slightly hazardous in case of skin contact (permeator), of ingestion |

| Lactic acid >98% | Any | Any | CAUTION: Corrosive to metals, category 1 Skin corrosion, categories 1A,1B,1C Serious eye damage, category 1 |

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) | Any | Any | |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Any | Any | CAUTION: Acute toxicity (oral, dermal, inhalation), category 4 Skin irritation, category 2 Eye irritation, category 2 Skin sensitisation, category 1 Specific Target Organ Toxicity – Single exposure, category 3 |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) | Any | Any | This material can be an irritant, contact with eyes and skin should be avoided. Inhalation of dust may be irritating to the respiratory tract. |

| 4′,6-Diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) | Any | Any | Cell permeable fluorescent minor groove-binding probe for DNA. Causes skin irritation. May cause an allergic skin reaction. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Ice | Any | NA | The DAPI solution has to be kept on ice. |

| Fluorescent microscope | AxioScope A1, Axiocam ICm1 from Zeiss or other | Any fluorescent microscope can be used for determining meristem length. | |

| Microscopic slide | Any | Any | |

| Cover glass | Any | Any | |

| Tweezers | Any | Any | Tweezers are needed for unfolding the rolled maize leaf right after harvesting in order to cut a proper sample for cell length and meristem length measurements. |

| Image-analysis software | Axiovision (Release 4.8) from Zeiss | NA | The software can be downloaded at: http://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en_de/downloads/axiovision.html. Other softwares such as ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) could be used as well. |

| Microscope equipped with DIC | AxioScope A1, Axiocam ICm1 from Zeiss or other | Any microscope, equipped with differential interference contrast (DIC) can be used to measure cell lengths. | |

| R statistical analysis software | R Foundation for Statistical Computing | NA | Open source; Could be downloaded at https://www.r-project.org/ |

| R script | NA | NA | We use the kernel smoothing function locpoly of the Kern Smooth package (Wand MP, Jones MC. Kernel Smoothing: Chapman & Hall/CRC (1995)). The script is available for Mac and Windows upon inquire with the corresponding author. We have versions for Mac and Windows. |

References

- Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S. Quantitative analyses of cell division in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 60, 963-979 (2006).

- Silk, W. K., Erickson, R. O. Kinematics of Plant-Growth. J. Theor. Biol. 76, 481-501 (1979).

- Rymen, B., Coppens, F., Dhondt, S., Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S., Hennig, L., Köhler, C. Kinematic Analysis of Cell Division and Expansion. Plant Developmental Biology. , (2010).

- Avramova, V., Sprangers, K., Beemster, G. T. S. The Maize Leaf: Another Perspective on Growth Regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 787-797 (2015).

- Rymen, B., et al. Cold nights impair leaf growth and cell cycle progression in maize through transcriptional changes of cell cycle genes. Plant Physiol. 143, 1429-1438 (2007).

- Muller, B., Reymond, M., Tardieu, F. The elongation rate at the base of a maize leaf shows an invariant pattern during both the steady-state elongation and the establishment of the elongation zone. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1259-1268 (2001).

- Beemster, G. T. S., Masle, J., Williamson, R. E., Farquhar, G. D. Effects of soil resistance to root penetration on leaf expansion in wheat (Triticum aestivum L): Kinematic analysis of leaf elongation. J. Exp. Bot. 47, 1663-1678 (1996).

- Bernstein, N., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Development of Sorghum Leaves under Conditions of Nacl Stress – Spatial and Temporal Aspects of Leaf Growth-Inhibition. Planta. 191, 433-439 (1993).

- Sylvester, A. W., Smith, L. G., Bennetzen, J. L., Hake, S. C. Cell Biology of Maize Leaf Development. Handbook of maize: It’s Biology. , (2009).

- Nelissen, H., et al. A Local Maximum in Gibberellin Levels Regulates Maize Leaf Growth by Spatial Control of Cell Division. Curr. Biol. 22, 1183-1187 (2012).

- Avramova, V., et al. Drought Induces Distinct Growth Response, Protection, and Recovery Mechanisms in the Maize Leaf Growth Zone. Plant Physiol. 169, 1382-1396 (2015).

- Picaud, J. C., et al. Total malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations as a marker of lipid peroxidation in all-in-one parenteral nutrition admixtures (APA) used in newborn infants. Pediatr. Res. 53, 406 (2003).

- Basu, P., Pal, A., Lynch, J. P., Brown, K. M. A novel image-analysis technique for kinematic study of growth and curvature. Plant Physiol. 145, 305-316 (2007).

- Vander Weele, C. M., et al. A new algorithm for computational image analysis of deformable motion at high spatial and temporal resolution applied to root growth. Roughly uniform elongation in the meristem and also, after an abrupt acceleration, in the elongation zone. Plant Physiol. 132, 1138-1148 (2003).

- Nelissen, H., Rymen, B., Coppens, F., Dhondt, S., Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S., DeSmet, I. . Plant Organogenesis. , (2013).

- Ben-Haj-Salah, H., Tardieu, F. Temperature Affects Expansion Rate of Maize Leaves without Change in Spatial-Distribution of Cell Length – Analysis of the Coordination between Cell-Division and Cell Expansion. Plant Physiol. 109, 861-870 (1995).

- Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S., Bultynck, L., Lambers, H. Can meristematic activity determine variation in leaf size and elongation rate among four Poa species? A kinematic study. Plant Physiol. 124, 845-855 (2000).

- Pettko-Szandtner, A., et al. Core cell cycle regulatory genes in rice and their expression profiles across the growth zone of the leaf. J. Plant Res. 128, 953-974 (2015).

- Poorter, H., Remkes, C. Leaf-Area Ratio and Net Assimilation Rate of 24 Wild-Species Differing in Relative Growth-Rate. Oecologia. 83, 553-559 (1990).

- Macadam, J. W., Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Effects of Nitrogen on Mesophyll Cell-Division and Epidermal-Cell Elongation in Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 89, 549-556 (1989).

- Tardieu, F., Granier, C. Quantitative analysis of cell division in leaves: methods, developmental patterns and effects of environmental conditions. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 555-567 (2000).

- Bernstein, N., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Development of Sorghum Leaves under Conditions of Nacl Stress – Possible Role of Some Mineral Elements in Growth-Inhibition. Planta. 196, 699-705 (1995).

- Erickson, R. O., Sax, K. B. Rates of Cell-Division and Cell Elongation in the Growth of the Primary Root of Zea-Mays. P. Am. Philos. Soc. 100, 499-514 (1956).

- Beemster, G. T. S., Baskin, T. I. Analysis of cell division and elongation underlying the developmental acceleration of root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 116, 1515-1526 (1998).

- Goodwin, R. H., Stepka, W. Growth and differentiation in the root tip of Phleum pratense. Am. J. Bot. 32, 36-46 (1945).

- Hejnowicz, Z. Growth and Cell Division in the Apical Meristem of Wheat Roots. Physiologia Plantarum. 12, 124-138 (1959).

- Gandar, P. W. Growth in Root Apices .1. The Kinematic Description of Growth. Bot. Gaz. 144, 1-10 (1983).

- Baskin, T. I., Cork, A., Williamson, R. E., Gorst, J. R. Stunted-Plant-1, a Gene Required for Expansion in Rapidly Elongating but Not in Dividing Cells and Mediating Root-Growth Responses to Applied Cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 107, 233-243 (1995).

- Sacks, M. M., Silk, W. K., Burman, P. Effect of water stress on cortical cell division rates within the apical meristem of primary roots of maize. Plant Physiol. 114, 519-527 (1997).

- Granier, C., Tardieu, F. Spatial and temporal analyses of expansion and cell cycle in sunflower leaves – A common pattern of development for all zones of a leaf and different leaves of a plant. Plant Physiol. 116, 991-1001 (1998).

- De Veylder, L., et al. Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 13, 1653-1667 (2001).

- Kwiatkowska, D. Surface growth at the reproductive shoot apex of Arabidopsis thaliana pin-formed 1 and wild type. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1021-1032 (2004).

- Kutschmar, A., et al. PSK-alpha promotes root growth in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 181, 820-831 (2009).

- Vanneste, S., et al. Plant CYCA2s are G2/M regulators that are transcriptionally repressed during differentiation. Embo J. 30, 3430-3441 (2011).

- Eloy, N. B., et al. Functional Analysis of the anaphase-Promoting Complex Subunit 10. Plant J. 68, 553-563 (2011).

- Eloy, N. B., et al. SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome regulator is involved in early development and A-type cyclin stabilization. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 13853-13858 (2012).

- Dhondt, S., et al. SHORT-ROOT and SCARECROW Regulate Leaf Growth in Arabidopsis by Stimulating S-Phase Progression of the Cell Cycle. Plant Physiol. 154, 1183-1195 (2010).

- Baute, J., et al. Correlation analysis of the transcriptome of growing leaves with mature leaf parameters in a maize RIL population. Genome Biol. 16, (2015).

- Andriankaja, M., et al. Exit from Proliferation during Leaf Development in Arabidopsis thaliana: A Not-So-Gradual Process. Dev. Cell. 22, 64-78 (2012).

- Beemster, G. T. S., et al. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression profiles associated with cell cycle transitions in growing organs of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138, 734-743 (2005).

- Spollen, W. G., et al. Spatial distribution of transcript changes in the maize primary root elongation zone at low water potential. Bmc Plant Biol. 8, (2008).

- Candaele, J., et al. Differential Methylation during Maize Leaf Growth Targets Developmentally Regulated Genes. Plant Physiol. 164, 1350-1364 (2014).

- West, G., Inze, D., Beemster, G. T. S. Cell cycle modulation in the response of the primary root of Arabidopsis to salt stress. Plant Physiol. 135, 1050-1058 (2004).

- Zhang, Z., Voothuluru, P., Yamaguchi, M., Sharp, R. E., Peck, S. C. Developmental distribution of the plasma membrane-enriched proteome in the maize primary root growth zone. Front. Plant Sci. 4, (2013).

- Bonhomme, L., Valot, B., Tardieu, F., Zivy, M. Phosphoproteome Dynamics Upon Changes in Plant Water Status Reveal Early Events Associated With Rapid Growth Adjustment in Maize Leaves. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 11, 957-972 (2012).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Growth-Rates and Assimilate Partitioning in the Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades at High and Low Irradiance. Plant Physiol. 90, 1201-1206 (1989).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J., Spollen, W. G. Diurnal Growth of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades .2. Dry-Matter Partitioning and Carbohydrate-Metabolism in the Elongation Zone and Adjacent Expanded Tissue. Plant Physiol. 86, 1077-1083 (1988).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Growth-Rates and Carbohydrate Fluxes within the Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 85, 548-553 (1987).

- Vassey, T. L., Shnyder, H. S., Spollen, W. G., Nelson, C. J. Cellular Characterisation and Fructan Profiles in Expanding Tall Fescue. Curr. T. Pl. B. 4, 227-229 (1985).

- Allard, G., Nelson, C. J. Photosynthate Partitioning in Basal Zones of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 95, 663-668 (1991).

- Spollen, W. G., Nelson, C. J. Response of Fructan to Water-Deficit in Growing Leaves of Tall Fescue. Plant Physiol. 106, 329-336 (1994).

- Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Carbohydrate-Metabolism in Leaf Meristems of Tall Fescue .1. Relationship to Genetically Altered Leaf Elongation Rates. Plant Physiol. 74, 590-594 (1984).

- Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Carbohydrate-Metabolism in Leaf Meristems of Tall Fescue .2. Relationship to Leaf Elongation Rates Modified by Nitrogen-Fertilization. Plant Physiol. 74, 595-600 (1984).

- Silk, W. K., Walker, R. C., Labavitch, J. Uronide Deposition Rates in the Primary Root of Zea-Mays. Plant Physiol. 74, 721-726 (1984).

- Granier, C., Inze, D., Tardieu, F. Spatial distribution of cell division rate can be deduced from that of p34(cdc2) kinase activity in maize leaves grown at contrasting temperatures and soil water conditions. Plant Physiol. 124, 1393-1402 (2000).

- Voothuluru, P., Sharp, R. E. Apoplastic hydrogen peroxide in the growth zone of the maize primary root under water stress.1. Increased levels are specific to the apical region of growth maintenance. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1223-1233 (2012).

- Wu, Y. J., Jeong, B. R., Fry, S. C., Boyer, J. S. Change in XET activities, cell wall extensibility and hypocotyl elongation of soybean seedlings at low water potential. Planta. 220, 593-601 (2005).

- Macadam, J. W., Nelson, C. J., Sharp, R. E. Peroxidase-Activity in the Leaf Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue .1. Spatial-Distribution of Ionically Bound Peroxidase-Activity in Genotypes Differing in Length of the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 99, 872-878 (1992).

- Macadam, J. W., Sharp, R. E., Nelson, C. J. Peroxidase-Activity in the Leaf Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue .2. Spatial-Distribution of Apoplastic Peroxidase-Activity in Genotypes Differing in Length of the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 99, 879-885 (1992).

- Beemster, G. T. S., De Vusser, K., De Tavernier, E., De Bock, K., Inze, D. Variation in growth rate between Arabidopsis ecotypes is correlated with cell division and A-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Plant Physiol. 129, 854-864 (2002).

- Kavanova, M., Lattanzi, F. A., Schnyder, H. Nitrogen deficiency inhibits leaf blade growth in Lolium perenne by increasing cell cycle duration and decreasing mitotic and post-mitotic growth rates. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 727-737 (2008).

- Macadam, J. W., Nelson, C. J. Secondary cell wall deposition causes radial growth of fibre cells in the maturation zone of elongating tall fescue leaf blades. Ann. Bot-London. 89, 89-96 (2002).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Diurnal Growth of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades .1. Spatial-Distribution of Growth, Deposition of Water, and Assimilate Import in the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 86, 1070-1076 (1988).

- Gastal, F., Nelson, C. J. Nitrogen Use within the Growing Leaf Blade of Tall Fescue. Plant Physiol. 105, 191-197 (1994).

- Vanvolkenburgh, E., Boyer, J. S. Inhibitory Effects of Water Deficit on Maize Leaf Elongation. Plant Physiol. 77, 190-194 (1985).

- Silk, W. K., Hsiao, T. C., Diedenhofen, U., Matson, C. Spatial Distributions of Potassium, Solutes, and Their Deposition Rates in the Growth Zone of the Primary Corn Root. Plant Physiol. 82, 853-858 (1986).

- Meiri, A., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Deposition of Inorganic Nutrient Elements in Developing Leaves of Zea-Mays L. Plant Physiol. 99, 972-978 (1992).

- Neves-Piestun, B. G., Bernstein, N. Salinity-induced inhibition of leaf elongation in maize is not mediated by changes in cell wall acidification capacity. Plant Physiol. 125, 1419-1428 (2001).

- Bouchabke, O., Tardieu, F., Simonneau, T. Leaf growth and turgor in growing cells of maize (Zea mays L.) respond to evaporative demand under moderate irrigation but not in water-saturated soil. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 1138-1148 (2006).

- Westgate, M. E., Boyer, J. S. Transpiration-Induced and Growth-Induced Water Potentials in Maize. Plant Physiol. 74, 882-889 (1984).

- Horiguchi, G., Gonzalez, N., Beemster, G. T. S., Inze, D., Tsukaya, H. Impact of segmental chromosomal duplications on leaf size in the grandifolia-D mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 60, 122-133 (2009).

- Fleury, D., et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana homolog of yeast BRE1 has a function in cell cycle regulation during early leaf and root growth. Plant Cell. 19, 417-432 (2007).

- Vlieghe, K., et al. The DP-E2F-like gene DEL1 controls the endocycle in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 15, 59-63 (2005).

- Boudolf, V., et al. The plant-specific cyclin-dependent kinase CDKB1;1 and transcription factor E2Fa-DPa control the balance of mitotically dividing and endoreduplicating cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 16, 2683-2692 (2004).

- Baskin, T. I., Beemster, G. T. S., Judy-March, J. E., Marga, F. Disorganization of cortical microtubules stimulates tangential expansion and reduces the uniformity of cellulose microfibril alignment among cells in the root of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135, 2279-2290 (2004).