個人の健康状態を監視するためのウェアラブルデバイスとのペアリングのためのアプリケーション

Summary

本プロトコルは、心理的尺度、GPS位置、心拍数、血中酸素飽和度、およびアプリケーションの操作手順を含むリアルタイムのオンサイトデータを収集するための非商用の自社開発アプリケーションを紹介します。2020年に台湾で実施された実証研究を応用例として使用しました。

Abstract

現在のプロトコルは、テクノロジーの統合を紹介することを目的としており、国立台湾大学(HLHP-NTU)のヘルシーランドスケープアンドヘルシーピープルラボによって開発されたHealthCloudアプリをスマートフォンやスマートウォッチに採用して、ユーザーのリアルタイムの心理的および生理学的反応と環境情報を収集するための詳細な説明を提供します。ランドスケープやアウトドアレクリエーション研究の現場調査では、個人データの多次元的な側面を測定することが困難な場合があるため、柔軟で統合された研究方法が提案されました。2020年に国立台湾大学キャンパスで実施した実地調査を応用例として使用しました。無効なサンプルを除外した後、385人の参加者のデータセットを使用しました。実験中、参加者は、心拍数と心理的スケールの項目がいくつかの環境指標とともに測定されたときに、キャンパスを30分間歩き回るように求められました。この研究は、オンサイト研究が周囲の要因に一致するリアルタイムの人間の反応を追跡するのに役立つ可能なソリューションを提供することを目的としていました。アプリの柔軟性により、ウェアラブルデバイスでの使用は、学際的な調査研究の優れた可能性を示しています。

Introduction

リアルタイムのデータ収集

日常生活において、人々は多くの点で物理的環境の恩恵を受けています。たとえば、心理的1や心拍数回復2などの肯定的な結果が広く見出されています。さらに、温度や湿度などの環境要因とメンタルヘルスとの関係が議論されています3,4。研究はまた、心拍数やストレスなどの生理学的反応と心理的反応の間の関連を調査しました5,6,7,8。自然への曝露による心理的および生理学的利益の幅広い証拠は、十分に管理された実験室研究9,10で発見されており、これはこの分野の多様な影響力のある要因を表していない可能性があります。したがって、リアルタイムの人間の反応間の関係を測定するために、現場での研究は、実験室シミュレーションよりも実際のシナリオの経験と環境への反応を反映する方が良いと考えられています11。さらに、環境に対する人間の反応は、文脈に依存する可能性があります12。人々の心理的・生理学的健康と環境の質との関係を理解することの重要性を考えると、さまざまな情報を収集できるリアルタイムの自己追跡測定が緊急に必要とされています。

生態学的瞬間評価(EMA)または経験サンプリング法(ESM)は、オンサイト研究の解決策を表す可能性があります13,14。EMAとESMは、実際のシナリオで現場で人間の瞬間的な反応を評価することを目的としています15。自己追跡技術を採用することにより、反応、反応、および現場での経験を新鮮に測定することができます14。参加者は、いわゆるシグナル条件サンプリングスキーム15で評価を実施するために、テキストや通知などのシグナルを介して通知される。「EMA」という用語は主に健康関連の研究13で使用されますが、「ESM」はレジャーおよびアウトドアレクリエーションの研究16で使用される傾向があります。それにもかかわらず、これらの用語は時折同じ意味で使用されます12。

EMAを環境調査研究に適用する可能性は、Beute et al.12によって議論され、EMAは単に「自然」または「都市」よりも多様な環境に対処することができると指摘しました。例えば、外来計測(GPS位置追跡など)を採用することにより、歩行中の生理学的反応をリアルタイムの位置データセットと照合することができ、環境タイプおよび環境特性のより豊かな空間分解能を提供する7。さらに、EMAによって許可されたリアルタイムのデータ収集は、高い生態学的妥当性を保証し、実験室での研究からの補完的な視点を提供します。

ますます多くの現場での実証研究が、日常生活や研究目的で個人の健康状態を監視するためにウェアラブルデバイスとスマートフォンを採用しています17,18,19,20。これらのデバイスの両方を採用することは、スマートフォン12のみを使用するよりも多くの利点を提供し得る。第1に、スマートウォッチを使用した場合のアクセス時間は、電話機21を使用した場合よりも短く、中断の負担が軽減される可能性がある。第二に、時計はスマートフォン22よりも身体に近いことを提供し、電話はデータを保存およびアップロードするための瞬間的なデータベースとして使用することができる。第三に、最近のスマートウォッチは、心拍数の変動、心電図(ECG)、血圧23、24、25、26、27などのさまざまなパラメーターに複数のセンサーを提供します。人間の反応の個人的および全体的な側面は、特定の活動を推測することができます12。最後に、スマートフォンは通常、スマートフォンベースの研究のためにポケットに入れて持ち歩き、アンケートに関しては、スマートウォッチを使用する場合と比較して余分な作業を行う必要があります。

しかし、心理的および生理学的結果と環境情報との関係を調査した研究はほとんどありません。そこで本研究では、スマートウォッチやスマートフォンなどのウェアラブル機器に非商用の自社開発アプリ「HealthCloud」を採用し、心理的、生理的、環境的情報をリアルタイムに収集する。

自社開発アプリとウェアラブル機器

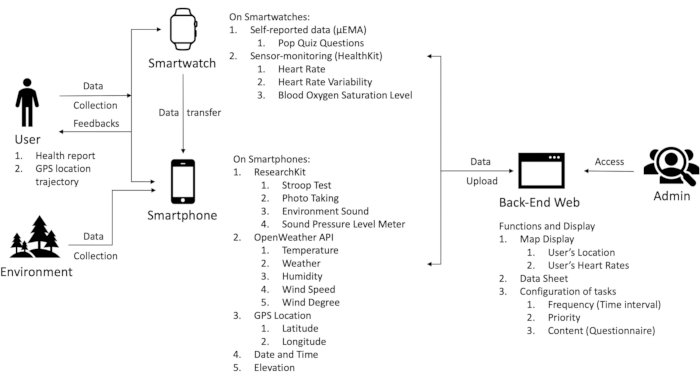

ウェアラブルデバイスで使用するアプリは、国立台湾大学(HLHP-NTU)のヘルシーランドスケープアンドヘルシーピープルラボによって開発され、人間の反応と環境データを追跡するためのよりアクセスしやすく柔軟な方法を提供し、研究者が人間の健康と環境情報の関係をさらに分析できるようにします(図1)。

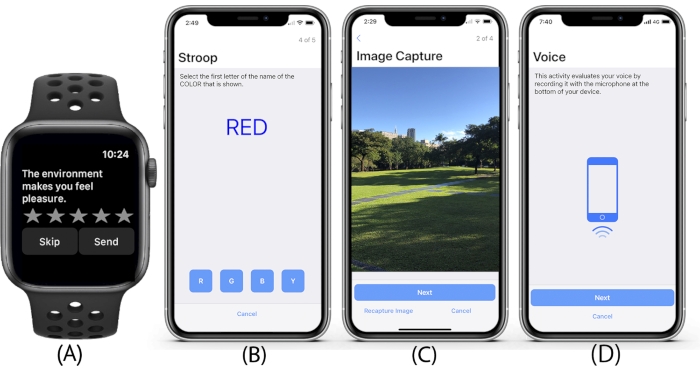

iOSベースのこのアプリは、複数のタスクとパッシブデータ収集機能を提供します。このアプリは、ポップクイズの質問を通じて測定された心理的スケールのアイテムなど、スマートウォッチの自己申告データを収集し、ユーザーは回答を1つ星から5つ星まで評価して、すばやく簡単に評価できます。このタイプの質問介入は、マイクロインタラクションの一種と見なすことができます-EMA(μEMA)-スマートウォッチ-EMA28よりも注意が少なく、応答率が高いin situデータ収集方法。心拍数、心拍変動、血中酸素飽和度など、センサーで監視される生理学的反応データは、iOSの機能を使用して測定できます。心拍数は、フォトプレチスモグラフィ29と呼ばれる技術を使用して、スマートウォッチの光学式心拍センサーを介して測定されます。アプリは、光に敏感なフォトダイオードを備えた緑色のLEDライトを使用して血流量を検出し、毎分心拍数も計算されます。心拍数変動(HRV)と血中酸素濃度(SpO2)は、アプリを使用して検出できます。スマートフォンの場合、ストループテスト(図2B)、画像キャプチャタスク(図2C)、環境サウンドタスク(図2D)などのタスクは、相対湿度、天候、高度などの周囲条件データがいくつかのアプリケーションプログラミングインターフェイスから受動的に収集されます。

図 1: アプリの概要。 スマートウォッチ、スマートフォン、データベース上のアプリの機能。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

図 2: アプリのタスク。 アプリで使用できるタスクの例:左から右に、(A)ポップアップの質問があります。(B)ストループテスト。 (C)画像キャプチャタスク。(D)環境サウンドタスク。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

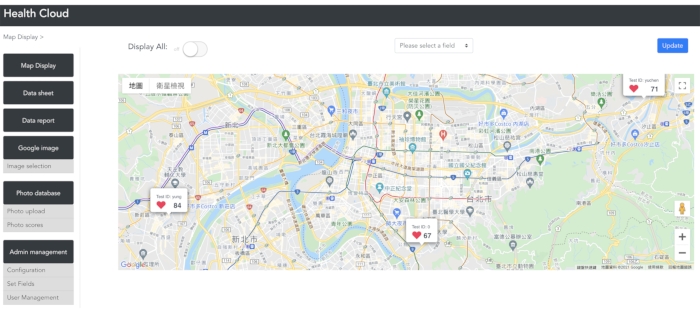

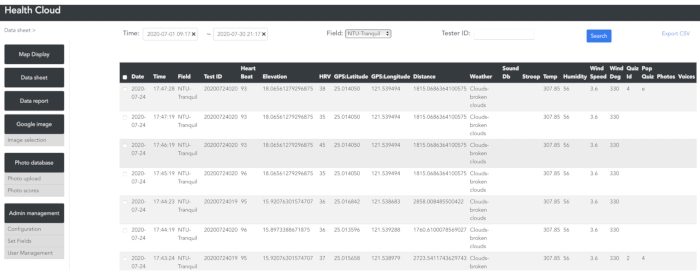

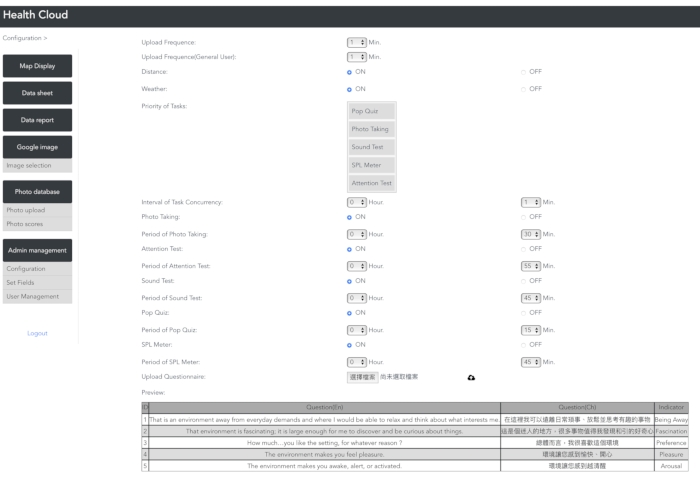

すべてのデータはバックエンドのウェブサイトにアップロードされます(共同研究者へのアクセス、資料表を参照)。このWebサイトは、ユーザーの現在地と心拍数を示す地図表示(図3)、データを閲覧および抽出するためのデータシート(図4)、タスクの頻度、優先度、および内容を変更するためのタスク構成(図5)など、いくつかの主要な機能を提供します。このような優れた柔軟性と幅広い測定により、研究者は研究目的に応じて前述のタスク機能を簡単に選択できます。さらに、このアプリはユーザーと研究者の両方に利益をもたらすことができます。このアプリは、回答した質問と選択したルートに応じて、ヘルスレポートとGPS位置の軌跡(図6)を提供します。したがって、彼らはその日の健康状態の迅速なアイデアを取得し、彼らの健康データを追跡し続けることができます。

図 3: アプリ データベースに表示されるマップ。 アプリデータベースの地図表示は、場所や心拍数などの現在の情報を研究者に提供します。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

図 4: アプリ データベースのデータシート。 アプリ データベース内の表示マップのデータ レポートで、時間、フィールド、またはテスター ID をフィルター処理してデータをエクスポートできます。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

図 5: アプリ データベースのタスク構成。 タスクの優先順位、時間間隔、言語、およびアンケートの内容を変更できます。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

図 6: アプリ ユーザーの正常性レポート。 アプリを使用した後、ユーザーは自動的に生成された一連の個々の結果を受け取ることができます。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

代表的な研究

スマートフォンやスマートウォッチのアプリを使用したデータ収集の多様な次元の統合を紹介するために、2020年に台湾の台北市にある国立台湾大学のキャンパスで in situ 調査が実施されました。研究の参加者は、実験の1週間前にオンラインフォームを通じて国立台湾大学のソーシャルメディアファンページで募集されました。フォームには、研究の目的、プロセス、場所、参加条件、着用する研究機器の概略図、読者が参加する意思と参加できる時間を示すためのスペースが含まれていました。完了後、参加者はスケジュールの2日前に実験の正確な時間と場所を電子メールで通知されました。この研究では、心理的変化、生理学、身体活動(歩行)、および音と色の知覚を調べているため、参加者は次の条件を満たしました:(1)20〜36歳、(2)身体的および精神的健康、(3)中枢神経系に影響を与える薬物を定期的に使用していない、(4)妊娠または授乳していない、(5)心血管疾患の病歴がない、 (6)徒歩30分以上歩ける、(7)色を識別できる。

実験当日は、参加者にスマートフォンとスマートウォッチ1セット、ルートマップが提供されました。研究者は、研究の目的、研究プロセス、ウェアラブルデバイス、および研究プロセスで注意が必要な事項について、参加者に統一された説明を行いました。歩行中、心理的反応は5分ごとにポップクイズタスクを使用して評価され、心拍数などの生理学的反応はスマートウォッチのセンサーによって毎分測定されました。実験後、参加者には200NTD相当のギフトカード(~7米ドル)が支給されました。

心理測定では,景観の選好と,知覚修復尺度ショートバージョン30の2つの側面,すなわち「離れている」と「魅力」を考慮しました。これらの側面は、参加者に「これは日常の要求から離れており、リラックスして興味のあることを考えることができる場所である」と「その場所は魅力的です。それは私が物事を発見し、興味を持つのに十分な大きさです」と、注意回復理論に基づいて環境の修復要因に対する個人の認識を測定するために、(1)「強く同意しない」から(5)「強く同意する」までの5段階のリッカート尺度で31。景観の好みは、5段階のリッカート尺度を使用して評価され、(1)「非常に少ない」から(5)「非常に多い」までの1つの質問で、「何らかの理由で、設定がどれだけ好きですか?」という1つの質問がありました。アンケートは、5分間隔で「ポップクイズ」タスクを使用して送信され、参加者は5分ごとにアンケートを受け取りました。

生理学的測定のために、歩行中の心拍数(HR)を使用して、1分の時間間隔で参加者の生理学的結果を表しました。GPSデータ(緯度経度)、気温、相対湿度、風速、風度などの環境情報をスマートフォンで収集しました。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

研究の目的と重要な調査結果

スマートフォンやスマートウォッチなどのウェアラブルデバイスは、生理学的指標または症候群32,33,34、心理状態22,35を調査するために広く使用されています。環境情報、または行動18,36。?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

台湾農業評議会は、2018年から2020年にかけて、研究プロジェクトとHealthCloudアプリの開発に資金を提供しました[109農業科学-7.5.4-補足-#1(1)]([109-7.5.4  —

— #1(1)])。

#1(1)])。

Materials

| Apple Watch 6 | Apple | For the use of the HealthCloud app, such as Pop-up questions, heart rates measurement. | |

| iPhone | Apple | For the use of the HealthCloud app, such as GPS location collection, weather data colledction, data storage, data transfer. | |

| HealthCloud | Self-developed | The HealthCloud app, adopting Apple Watch and iPhone, was developed by Healthy Landscape and Healthy People Lab, National Taiwan University (HLHP-NTU) to track human responses. It adopted several APIs such as HealthKit, ResearchKit, Weather API and AppleWatch applications including Breathe app, and Blood Oxygen app to collect physiological status and psychological states, and environmental data in aims of further analyzing the relationships between human health and the environmental information. The link to the app in APP Store is as following: https://apps.apple.com/tw/app/healthcloud/id1446179518?l=en |

|

| backend website | The backend website of HealthCloud app for the use of the configuration of the tasks, data exportation, and the display of users. http://healthcloud.hort.ntu.edu.tw/ |

||

| HealthKit | Apple | For the use of retrieving the data of physiological responses such as heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood oxygen saturation level. The link to the HealthKit: https://developer.apple.com/documentation/healthkit |

|

| ResearchKit | Apple | This kit includes a variety of tasks for the use of research purposes. The functions adopted in HealthCloud app include Image Capture task, environment sound task, Stroop Test, to the Pop Questions of psychological state measurements such as perceived restorativeness scale, landscape preferences. The link to the ResearchKit: https://www.researchandcare.org/ |

|

| Weather API | OpenWeather | For the use of collecting the real-time environmental data, including humidity, weather, global positioning system location, altitudes, etc., from the nearest weather station. The link to the Weather API: https://openweathermap.org/api |

|

| Breathe app | Apple | For the use of assessing the real-time heart rate variability (HRV). This app was not included in the procedures of this pilot study. However, the HealthlCloud is now capable of retrieving the HRV data collected from Breathe app. The link to the Breathe app: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/breathe/id1459455352 |

|

| Blood Oxygen app | Apple | For the use of assessing the real-time Blood Oxygen Concentration level (SpO2). The latest version of HealthlCloud is capable of retrieving the SpO2 data collected from app. This app was not included in the procedures of this pilot study. However, The measurement of Blood Oxygen app: https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT211027 The link to the Blood Oxygen app: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/breathe/id1459455352" |

|

| IBM SPSS Statistics 25 | IBM | For the use of statistical analysis. The link to the Blood Oxygen app: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-25 |

References

- Purcell, T., Peron, E., Berto, R. Why do preferences differ between scene types. Environment and Behavior. 33 (1), 93-106 (2001).

- Engell, T., Lorås, H. W., Sigmundsson, H. Window view of nature after brief exercise improves choice reaction time and heart rate restoration. New Ideas in Psychology. 58, 100781 (2020).

- Ding, N., Berry, H. L., Bennett, C. M. The importance of humidity in the relationship between heat and population mental health: Evidence from Australia. PLOS ONE. 11 (10), 0164190 (2016).

- Majeed, H., Lee, J. The impact of climate change on youth depression and mental health. The Lancet Planetary Health. 1 (3), 94-95 (2017).

- Merkies, K., et al. Preliminary results suggest an influence of psychological and physiological stress in humans on horse heart rate and behavior. Journal of Veterinary Behavior. 9 (5), 242-247 (2014).

- Delaney, J. P. A., Brodie, D. A. Effects of short-term psychological stress on the time and frequency domains of heart-rate variability. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 91 (2), 515-524 (2000).

- South, E. C., Kondo, M. C., Cheney, R. A., Branas, C. C. Neighborhood blight, stress, and health: a walking trial of urban greening and ambulatory heart rate. American Journal of Public Health. 105 (5), 909-913 (2015).

- Rimmele, U., et al. Trained men show lower cortisol, heart rate and psychological responses to psychosocial stress compared with untrained men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 32 (6), 627-635 (2007).

- Jo, H., Song, C., Miyazaki, Y. Physiological benefits of viewing nature: A systematic review of indoor experiments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16 (23), 4739 (2019).

- Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L. M., Knight, T. M., Pullin, A. S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health. 10 (1), 1-10 (2010).

- Olafsdottir, G., et al. Health benefits of walking in nature: A randomized controlled study under conditions of real-life stress. Environment and Behavior. 52 (3), 248-274 (2020).

- Beute, F., De Kort, Y., IJsselsteijn, W. Restoration in its natural context: How ecological momentary assessment can advance restoration research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (4), 420 (2016).

- Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., Hufford, M. R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 4, 1-32 (2008).

- Hektner, J. M., Schmidt, J. A., Csikszentmihalyi, M. . Experience sampling method: Measuring the quality of everyday life. , (2007).

- Robbins, M. L., Kubiak, T., Mostofsky, D. I. Ecological momentary assessment in behavioral medicine: Research and practice. The Handbook of Behavioral Medicine. 1, 429-446 (2014).

- Fave, A. D., Bassi, M., Massimini, F. Quality of experience and risk perception in high-altitude rock climbing. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 15, 82-98 (2003).

- Ates, H. C., Yetisen, A. K., Güder, F., Dincer, C. Wearable devices for the detection of COVID-19. Nature Electronics. 4 (1), 13-14 (2021).

- Cagney, K. A., Cornwell, E. Y., Goldman, A. W., Cai, L. Urban mobility and activity space. Annual Review of Sociology. 46, 623-648 (2020).

- Chaix, B. Mobile sensing in environmental health and neighborhood research. Annual Review of Public Health. 39, 367-384 (2018).

- York Cornwell, E., Goldman, A. W. Neighborhood disorder and distress in real time: Evidence from a smartphone-based study of older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 61 (4), 523-541 (2020).

- Ashbrook, D. L., Clawson, J. R., Lyons, K., Starner, T. E., Patel, N. Quickdraw: The impact of mobility and on-body placement on device access time. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’08). , 219-222 (2008).

- Hänsel, K., Alomainy, A., Haddadi, H. Large scale mood and stress self-assessments on a smartwatch. Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing: Adjunct. , 1180-1184 (2016).

- Karmen, C. L., Reisfeld, M. A., McIntyre, M. K., Timmermans, R., Frishman, W. The clinical value of heart rate monitoring using an apple watch. Cardiology in Review. 27 (2), 60-62 (2019).

- Hernando, D., Roca, S., Sancho, J., Alesanco, &. #. 1. 9. 3. ;., Bailón, R. Validation of the apple watch for heart rate variability measurements during relax and mental stress in healthy subjects. Sensors. 18 (8), 2619 (2018).

- Shcherbina, A., et al. Accuracy in wrist-worn, sensor-based measurements of heart rate and energy expenditure in a diverse cohort. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 7 (2), 3 (2017).

- Samol, A., et al. Patient directed recording of a bipolar three-lead electrocardiogram using a smartwatch with ECG function. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (154), e60715 (2019).

- Verdecchia, P., Angeli, F., Gattobigio, R. Clinical usefulness of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 15, 30-33 (2004).

- Ponnada, A., Haynes, C., Maniar, D., Manjourides, J., Intille, S. Microinteraction ecological momentary assessment response rates: Effect of microinteractions or the smartwatch. Proceedings of the ACM on interactive, mobile, wearable and ubiquitous technologies. 1 (3), 1-16 (2017).

- . Monitor your heart rate with Apple Watch Available from: https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT204666 (2021)

- Berto, R. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 25 (3), 249-259 (2005).

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 15 (3), 169-182 (1995).

- Firth, J., et al. Can smartphone mental health interventions reduce symptoms of anxiety? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders. 218, 15-22 (2017).

- Turakhia, M. P., et al. Rationale and design of a large-scale, app-based study to identify cardiac arrhythmias using a smartwatch: The Apple Heart Study. American Heart Journal. 207, 66-75 (2019).

- Weenk, M., et al. Continuous monitoring of vital signs using wearable devices on the general ward: Pilot study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 5 (7), 91 (2017).

- Wang, R., et al. StudentLife: Assessing mental health, academic performance and behavioral trends of college students using smartphones. Proceedings of the 2014 ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing. , 3-14 (2014).

- Vhaduri, S., Munch, A., Poellabauer, C. Assessing health trends of college students using smartphones. 2016 IEEE Healthcare Innovation Point-Of-Care Technologies Conference IEEE. HI-POCT. , 70-73 (2016).

- Ståhl, A., Höök, K., Svensson, M., Taylor, A. S., Combetto, M. Experiencing the affective diary. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing. 13 (5), 365-378 (2009).

- Khushhal, A., et al. Validity and reliability of the Apple Watch for measuring heart rate during exercise. Sports Medicine International Open. 1 (6), 206-211 (2017).

- Walsh, E. I., Brinker, J. K. Should participants be given a mobile phone, or use their own? Effects of novelty vs utility. Telematics and Informatics. 33 (1), 25-33 (2016).

- Enock, P. M., Hofmann, S. G., McNally, R. J. Attention bias modification training via smartphone to reduce social anxiety: A randomized, controlled multi-session experiment. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 38 (2), 200-216 (2014).

- Reid, S. C., et al. A mobile phone application for the assessment and management of youth mental health problems in primary care: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Family Practice. 12, 131 (2011).

- Huang, S., Qi, J., Li, W., Dong, J., vanden Bosch, C. K. The contribution to stress recovery and attention restoration potential of exposure to urban green spaces in low-density residential areas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (16), 8713 (2021).

- Doherty, S. T., Lemieux, C. J., Canally, C. Tracking human activity and wellbeing in natural environments using wearable sensors and experience sampling. Social Science & Medicine. 106, 83-92 (2014).

- Birenboim, A., Dijst, M., Scheepers, F. E., Poelman, M. P., Helbich, M. Wearables and location tracking technologies for mental-state sensing in outdoor environments. The Professional Geographer. 71 (3), 449-461 (2019).

- Kheirkhahan, M., et al. A smartwatch-based framework for real-time and online assessment and mobility monitoring. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 89, 29-40 (2019).