자기 보고 vs 재활용 행동 측정

English

Share

Overview

출처: 게리 레반도프스키,데이브 스트로메츠, 나탈리 시아로코-몬머스 대학교 의 연구소

실험 변수를 측정하는 데 따르는 과제 중 하나는 보다 정확한 측정을 생성하는 기술을 식별하는 것입니다. 종속 변수를 측정하는 가장 일반적인 방법은 참가자에게 자신의 감정, 생각 또는 행동을 설명하도록 요청하는 자기 보고서입니다. 그러나 사람들은 정직하지 않을 수 있습니다. 참가자에 대해 진정으로 알고 있다면, 그들이 실제로 상황에서 무엇을하는지 볼 필요가있을 수 있습니다.

이 비디오는 다그룹 실험을 사용하여 다른 사람들과 가깝게 느끼는 것이 자기 보고와 행동 관찰으로 측정된 환경 의식에 대한 더 유리한 태도를 초래하는지 확인합니다.

심리학 연구는 종종 다른 과학연구보다 더 높은 표본 크기를 사용합니다. 많은 수의 참가자가 연구 중인 인구가 더 잘 표현되도록 하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이 비디오에서는 한 명의 참가자만 사용하여 이 실험을 시연합니다. 그러나, 결과에 표현된 바와 같이, 우리는 실험의 결론에 도달하기 위하여 총 186명의 참가자를 이용했습니다.

Procedure

Results

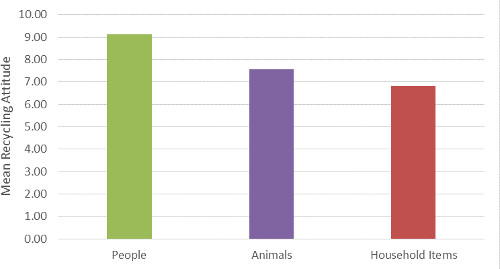

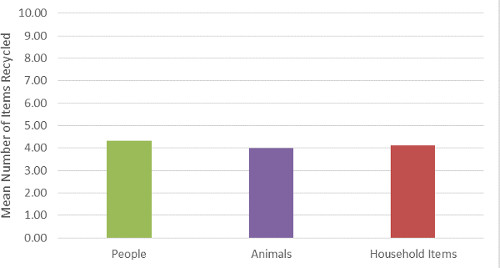

This procedure was repeated 185 times so that the results reflect data from 186 total participants. This large number of participants helps to ensure that the results reflect accurate mean numbers of items recycled. If this research were conducted using just one or two participants, it is likely that the results would have been much different, and not reflective of the greater population. Numbers in Figure 1 reflect participants’ average responses for the recycling questions on the survey. Numbers in Figure 2 represent the number of items (out of 10 total) the participant properly put in the recycling bin.

To determine if there were differences between the three picture conditions, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. The results indicated that though there were significant differences for the self-report survey, such that those in the feeling-close-to-people condition said they cared about recycling more, there were no significant differences when it came to participants’ actual behavior.

Figure 1. Average recycling attitude score by condition. Means were calculated from survey questions 3, 5, and 7.

Figure 2. Average number of properly recycled items by condition. Means were calculated from researcher’s observations of items placed in the recycling bin.

Applications and Summary

This multi-group experiment shows how participants’ feelings measured via a survey may not match up exactly with how they behave. In this case, participants reported more favorable attitudes (especially in the feeling-close-to-people condition), but when it came time to actually recycle, participants did not engage in the behavior.

This study replicates and extends previous research on self-reported recycling attitudes vs. actual recycling by Huffman et al., which showed that actual recycling was not associated with recycling attitudes and weakly correlated with self-reported recycling (i.e., did they recycle in the past).1

Several papers have emphasized the importance of behavioral measures, including Baumeister et al. and Lewandowski and Strohmetz.2,3 In each case, the key take away was that what a person actually does is more revealing than what the same person claims they will do. Though more challenging, measuring behavior is more informative.

References

- Huffman, A., Van Der Werff, B. R., Henning, J. B., & Watrous-Rodriguez, K. When do recycling attitudes predict recycling? An investigation of self-reported versus observed behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 382, 62-270. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.03.006 (2014).

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Funder, D. C. Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior?. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2 (4), 396-403. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00051.x (2007).

- Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., & Strohmetz, D. Actions can speak as loud as words: Measuring behavior in psychological science. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 3 (6), 992-1002. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00229.x (2009).

Transcript

Psychologists study many aspects of behavior by asking participants to report their own feelings or by directly observing their performance on specific tasks.

While self-report is often used, the authenticity of reported responses is difficult to determine. Therefore, observing participants’ behaviors during specific situations provides more reliable data.

Here, psychologists compare two forms of measurement, self-report and behavioral observation, to see if participants’ feelings reported through a survey correlate with their actual behavior.

This video demonstrates how to design, conduct, analyze, and interpret an experiment that investigates whether feeling close to others results in more favorable attitudes toward recycling.

During this experiment, participants are randomly divided into one of three groups: Feeling Close to People, Feeling Close to Animals, or No Connection. In this case, feeling close to people or animals involves perceived connections such as emotional attachments toward other people or animals.

Participants are then asked to view slides in which five pictures of people, animals, or non-living household items are shown, according to their group assignment. They are all then given the same two surveys to complete.

The first survey involves self-reported measures regarding environmental practices for protecting the natural world, whereas the second survey serves as a distraction while the researcher creates a scene for participant observations.

In this scene, the researcher pretends to eat lunch out of the participant’s sight. The meal includes a variety of recyclable and non-recyclable items.

After participants finish the second survey, they are asked to help clear off the table where lunch was eaten while the researcher steps away.

The dependent variables, the values reported on the first self-report survey and the number of items that each participant recycled when clearing the lunch table, are compared.

Participants in the Feeling Close to People group are hypothesized to have more favorable attitudes towards recycling and would recycle more items compared to the other groups.

To begin the study, meet the participant in the laboratory. Provide them with informed consent and discuss the overall procedure of the experiment.

Randomly assign each participant to one of three experimental groups: Feeling Close to People, Feeling Close to Animals, or No Connection, to view five pictures of people, animals, or non-living household items, respectively.

To assure that participants pay attention to the images, have each one write down how close or connected they feel to each image on a scale of 1 to 10.

After the participant views the images, hand them two surveys and instruct them to take a minute to consider each question and indicate how they feel.

While the participant fills out the second survey, pretend to eat lunch out of their sight.

After the participant completes the last survey, ask them to help clear off the lunch table while you prepare for the next part of the study. Have them place garbage into the garbage bin and recyclable items in the recycling bin.

When the participant finishes, record how many items were correctly placed into the recycling bin.

To conclude the experiment, debrief the participant and explain why deception was necessary for the experiment.

To analyze the data, first calculate the participants’ recycling attitude score for each condition by averaging the ratings from items 3, 5, and 7 on Survey 1. Note that the other items on this survey, as well as the second survey with yes or no questions, serve as distractors. Graph the mean recycling attitude by condition.

Notice that those in the Feeling Close to People condition indicated that they cared more about recycling than controls.

To determine the observed behavioral score, average the number of items that were counted as being correctly recycled for each condition. Graph the means across conditions. Notice that no significant differences were observed between groups.

Notice that participants who reported favoring attitudes towards recycling did not actually engage in the behavior. In other words, participants’ feelings were not correlated with their observed behaviors.

Now that you are familiar with how to compare self-report surveys against actual observed behavior, you can apply this approach to other forms of research.

Several studies have emphasized the importance of measuring behavior over the use of self-reports to better understand emotion. The most thorough studies collect data from a set of questionnaires, as well as correlate the answers with results from a goal-oriented behavioral task.

In addition, individuals with an addiction, such as cigarette smoking, do not always provide reliable answers to self-report questions. Researchers must use alternative methods, such as fMRI or PET imaging, to better understand smoking behavior.

Finally, self-report questionnaires about sleep are only as informative as the individual’s memory or awareness of their sleep behavior. Therefore, using polysomnography to observe participants during sleep is especially useful when trying to understand abnormal occurrences.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s introduction to compare and contrast measurements of self-reporting and observed behavior. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design and conduct this type of study by administering surveys and directly monitoring behavior, as well as how to analyze and interpret the results.

Thanks for watching!