Função executiva e a tarefa de classificação do cartão de mudança dimensional

English

Share

Overview

Fonte: Laboratórios de Nicholaus Noles e Judith Danovitch – Universidade de Louisville

Os bebês nascem com recursos cognitivos incríveis à sua disposição, mas não sabem como usá-los efetivamente. Para aproveitar o poder de seus cérebros, os humanos devem desenvolver processos cognitivos de alto nível que gerenciam funções cerebrais básicas. Esses processos compõem o que os psicólogos chamam de função executiva. A função executiva é um fator-chave em muitos comportamentos auto-regulatórios, incluindo a formação de planos para resolver problemas, a negociação entre desejos e ações e a direcionação da atenção. Por exemplo, uma criança deve usar vários processos executivos para parar de brincar com brinquedos e começar a limpar seu quarto. Esses processos incluem inibição (para parar o que estão fazendo), planejamento (para determinar quais ações precisam ser realizadas para limpar a sala) e controle de atenção (para permanecer na tarefa até que a limpeza seja feita). Uma quebra da função executiva durante qualquer uma dessas etapas levaria o quarto a permanecer sujo.

Desenvolver a função executiva é um dos principais desafios enfrentados pelas crianças à medida que amadurecem. Alguns elementos da função executiva só podem ser dominados com a prática, e as áreas cerebrais ligadas à função executiva, especificamente o córtex pré-frontal, desenvolvem-se lentamente ao longo do desenvolvimento, continuando a crescer e se organizar até que um indivíduo atinja seus vinte anos. As primeiras demonstrações da função executiva têm sido ligadas ao autocontrole e aos resultados comportamentais em crianças, bem como sucessos mais tarde na vida. Relacionado, a função executiva é prejudicada em crianças diagnosticadas com transtorno do déficit de atenção e hiperatividade (TDAH) e transtornos do espectro autista.

Este experimento demonstra como avaliar a função executiva em crianças usando a Tarefa de Classificação de Cartão de Mudança Dimensional, desenvolvida pelo Dr. Philip Zelazo e colegas. 1

Procedure

Results

In the pre-switch phase of the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task, children are building up patterns of thinking and attention, and those mental activities guide their physical responses. They learn to pay special attention to color, to ignore shape, and to place cards into the relevant trays. The post-switch phase requires children to shift their attention to a new dimension, which they had to actively ignore in the prior task, and to overcome their tendency to perform certain physical actions (e.g., putting the card in the box on the right when it is blue) in favor of an alternative action. Failing to inhibit either the prior focus of their attention or the learned action results in poor sorting accuracy during the post-switch phase.

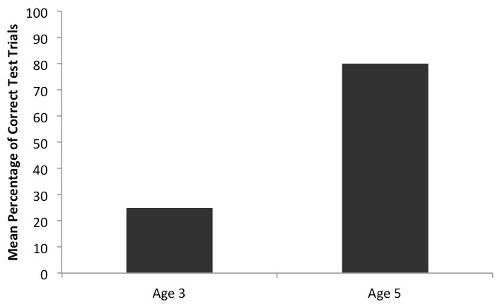

After learning to complete the pre-switch color game, children’s responses diverge by age (Figure 1). Three-year-olds typically have a very difficult time transitioning from the first game to a new game that uses the same materials but different rules. They fail to inhibit their recently learned patterns of thinking and acting. In contrast, most five-year-olds pass the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task. This success is interpreted as evidence of their emerging development in the domain of executive function.

Figure 1. The percentage of correct test trials completed by each child on average. Children scoring 80% or more “pass” the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task.

Applications and Summary

The Dimensional Change Card Sort Task is a tool designed to evaluate children’s executive function. The basic version described here can be used to effectively evaluate the executive function of 3- to 5-year-old children. However, there are permutations of this task that can be used to characterize executive function in children up to age 7. This task can also be used diagnostically to identify children with particularly poor executive function, which can be indicative of developmental delay, mental retardation, certain kinds of brain damage, or a clinical disorder, such as ADHD or Autism Spectrum Disorder. Generally, executive function is correlated with problem solving and self- and social-understanding.

Critically, there are many situations where important factors, such as intelligence, diverge from good decision-making. For example, choosing to go to a party instead of studying is a decision that many college students make, even though the short-term fun of a party is obviously less valuable than the long-term payoff of studying. However, the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain related to executive function, is still developing in college-aged individuals, so it is much easier to understand why even smart young people sometimes make poor decisions.

References

- Zelazo, P.D. The dimensional change card sort (DCCS): A method of assessing executive function in children. Nature Protocols. 1, 297-301. (2006).

Transcript

Developing executive function is one of the key challenges faced by children as they age.

For example, a child must use several executive processes to stop playing with toys and start cleaning their room. Such processes include: inhibition—stopping what they’re doing, planning—the actions needed to clean the room, and attentional control—staying on task until the cleaning is done.

A breakdown of executive function during any of these steps would lead to the room remaining messy.

Importantly, decision-making processes improve across normal development, as associated brain regions—like the prefrontal cortex—mature slowly, well into an individual’s twenties.

This video demonstrates how to assess executive function in children—ages 3 to 5 years—by discussing the steps required to set-up and run an experiment involving the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task, as well as how to analyze the data and interpret the results.

In the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task, children switch from sorting cards by one feature to another. In this case, two target cards consist of a red boat and a blue rabbit and the 16 test cards are split evenly between pictures of red rabbits and blue boats.

This task consists of three phases. During the demonstration phase, each child is introduced to the target cards and the rules of the game. For example, in the color game, all cards of the same color go in the tray with the same color of target card.

Following the demonstration phase, children are exposed to the pre-switch phase—where patterns of thinking and attention are developed by learning to pay special attention to one feature, such as color, and to ignore the other, shape.

Once six test cards are sorted, children move on to the post-switch phase, where the game is changed from color- to shape-sorting.

This phase requires children to shift their attention to a new dimension, which they had been actively ignoring, and to overcome their tendency to perform the same physical actions. The number of correct responses during the post-switch phase trials is the dependent variable.

Three-year-olds typically have a very difficult time transitioning from the first game to a new game because they fail to inhibit their recently learned patterns of thinking and acting.

In contrast, most 5-year-olds do not have a problem transitioning to the new game, which suggests their emerging development of executive function.

Prior to the arrival of participants, make sure a chair and table are set-up with two trays and the target and test cards. Ensure the test cards are pseudo-randomized so that two cards of the same type are not in a row and that the first two cards contain a red rabbit and a blue boat.

After greeting the child, instruct him to sit within view of the trays and target cards. Next, describe the two target cards: Here is a blue rabbit and here is a red boat.

Introduce the pre-switch rules for the color game: Now, we’re going to play a card game. In the color game, all the blue ones go here, and all the red ones go here.

Draw a test card to demonstrate the rules to the child, label its color aloud, and then place it face down into the appropriate tray.

After repeating the rules, pick another card and label it. Then hand the card to the child and encourage him to place it face down in the appropriate tray, and help if necessary.

Following the demonstration phase, introduce the pre-switch rules: select a card, label it for the child, and then ask him to sort it.

Once the child completes six trials, transition to the post-switch phase. Explain the rules now based on shape: Now we’re going to play a new game. We’re going to play the shape game. In the shape game, all the rabbits go here, and all the boats go here.

For the remaining six cards, select one, label it by shape, and hand it to the child for placement.

After the last card has been placed, thank the child for their participation.

To analyze the results, determine the number of correct responses during the post-switch trials for each child in the study and graph the mean results by age group.

A child that scores 80% or more on post-switch trials is said to have passed the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task assessment of executive function. As predicted, on average, the 5-year-olds passed, while the younger 3-year-olds did not, which highlights a critical age for the progression of executive function.

Now that you are familiar with the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task to evaluate children’s executive function, let’s look at other ways that experimental psychologists use it.

Researchers use permutations of this task diagnostically to identify children with particularly poor executive function, which can be indicative of developmental delay or a clinical disorder, such as ADHD or Autism Spectrum Disorder.

In addition, researchers examine decision-making in early adulthood because the prefrontal brain regions are still developing. This lag partly explains how even smart individuals make poor decisions—like choosing the short-term benefits of going to a party over the long-term benefits of studying for a test.

Other researchers have combined the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task and functional magnetic resonance imaging in order to investigate the role of various brain regions in executive function. Findings that suggest age-related differences in connectivity within areas, especially the lateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, provide insights into the neural mechanisms involved in card sorting performance.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s introduction to the development of executive function using the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task. Now you should have a good understanding of how to setup and perform the experiment, as well as analyze and assess the results.

Thanks for watching!