Catégories et inférences inductives

English

Share

Overview

Source : Laboratoires de Nicholaus mimine et Judith Danovitch — Université de Louisville

Il pourrait être possible pour le cerveau humain garder une trace de chaque personne, endroit ou chose rencontrée, mais ce serait un usage très inefficace du temps et de ressources cognitives. Au lieu de cela, les humains développent des catégories. Les catégories sont des représentations mentales des choses réelles qui peuvent être utilisés pour une variété d’usages. Par exemple, personnes peuvent utiliser les caractéristiques perceptuelles des animaux pour les placer dans une catégorie donnée. Alors, en voyant un poilu, à quatre pattes, queue-remuer, aboiement animal, une personne peut déterminer que c’est un chien. C’est l’un des nombreux exemples où les gens utilisent similitude perceptuel pour s’adapter à des expériences nouvelles dans leurs représentations mentales existantes.

Toutefois, l’adhésion catégorie est beaucoup plus que la peau profondément, surtout pour les représentations d’animaux. Frank Keil a démontré en utilisant une technique simple et puissante qui portait sur les différences entre les genres naturels et artefacts. Les genres naturels incluent animaux et autres organismes vivants, tandis qu’artefacts se composent en grande partie des choses inertes, tels que des tables ou des briques dorées. Dans son étude, Keil parlé enfants histoires naturelles sortes et artefacts qui ont subi des transformations obligeant à traverser les frontières catégoriques. Par exemple, il décrit un processus par étapes par lesquelles un raton laveur a été transformé en une créature qui ressemblait à une mouffette dans tous les sens. À la fin de l’histoire, le raton laveur était noir avec une bande blanche, et il a implanté des glandes qui fait sentir comme un putois, trop. Il a demandé aux enfants pour déterminer si l’animal qui en résulte est un raton laveur ou une mouffette. Il a utilisé une méthode similaire pour décrire la transformation d’un artefact pneu-an-dans une chaussure. Les réponses de l’enfant ont révélé des changements du développement intéressants dans Comment les gens pensent sur les artefacts et les genres naturels.

Cette vidéo montre comment l’étude de transformation de Frank Keil. 1

Procedure

Results

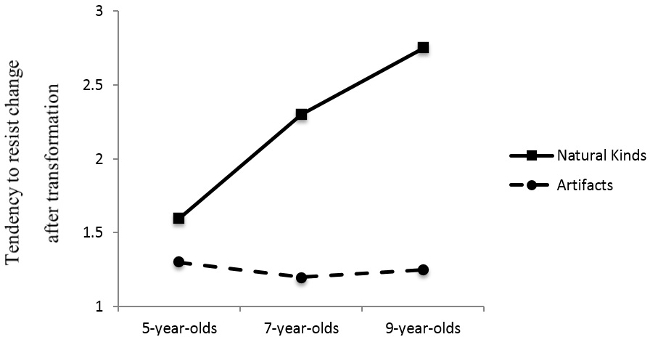

In order to have enough power to see significant results, researchers would have to test at least 18 children in each age group. Typically, when asked about artifacts, children in all three age groups conclude that what is seen confirms the categorical placement. If a tire is transformed into a rubber shoe, then it is a shoe and not a tire. In contrast, children presented with natural kinds reveal a developmental trend. Five-year-olds are either indecisive or see an animal’s posttransformation features as indicating their category membership. As children get older, they determine increasingly often that animals remain the same kind of thing in spite of any physical transformation they may undergo. This experiment demonstrates that children represent category membership as an internal, unchangeable aspect of animals increasingly as they get older, and this idea drives children’s intuitions about category membership (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The average tendency for children to resist shifts in category membership. Low numbers indicate that transforming a target’s features changes its category membership.

Applications and Summary

Frank Keil's work demonstrates that internal characteristics count. Children treat category membership as springing from internal characteristics that cause animals' appearances and behaviors, and children continue to have the intuition that animals belong to their category, even when appearances and behaviors change. Generally, this finding supports other work demonstrating that children use categorical information and not other cues, such as appearance, to guide their inferences about animals. For example, individuals can use categories to make inductive inferences, or educated guesses, based on their categorical knowledge. So, if a child knows it's dangerous to touch their pet cat when its tail is wagging, then they can make an inductive inference that any new, tail-wagging cat is also dangerous. These inferences, like the inferences of category membership in Keil's study, are driven by category membership and not necessarily appearance.

References

- Keil, F.C. Concepts, Kinds, and Cognitive Development. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA (1989).

Transcript

To organize the world and efficiently use cognitive resources, children learn to place objects, people, and locations into categories.

In a broad sense, a category—like fruits—is a mental representation of a collection of real things that share similar features, such as the presence of seeds.

In this instance, the characteristic of having seeds is a “hidden” or internal feature—one not easily observed—that can be used to link items to form a category.

However, sometimes the feature—or features—on which a category is based can be readily perceived. For example, if a child sees an animal that has four legs, a tail, and barks, they’ll likely categorize it as a dog.

Importantly, children can take what they know about a single item belonging to a category, like their pet dog, and use that information to identify and make inductive inferences—educated guesses—about unfamiliar category members.

For example, if a child knows that their dog wags its tail when it’s happy, then they can guess that a new tail-wagging dog is also happy.

Based on the pioneering work of Frank Keil, this video explores how to investigate the criteria 5- to 9-year-olds use to categorize objects by designing stimuli that cross categorical boundaries, and explains how to perform such a transformational study and interpret categorization data. We will also look at how psychologists use this technique in other applications, for example to explore how children make inferences.

In this experiment, researchers present 5-, 7-, and 9-year-old children with 16 stories in which items are physically altered so that they resemble something else.

Eight of these stories center around living animals or naturally occurring objects, like zebras or diamonds—collectively called natural kinds—and eight deal with man-made, non-living items referred to as artifacts, such as cups or pots.

For instance, in a natural kind-focused transformation story, children are first shown a “before” image of a naturally occurring item or animal, such as a raccoon.

They’re then told that doctors surgically transformed this thing, for example by attaching containers of foul-smelling liquid to the raccoon, and shaving and dying portions of its fur so that it becomes black and white with a puffy tail.

Importantly, the researcher emphasizes that such operations result in the item being transformed so that it represents a different object of the same type: a living natural kind is made to look like another living natural kind.

Children are finally presented with an “after” image of the subject, and asked how they’d categorize it post-surgery—if it’s a raccoon or a skunk.

Their answers are rated on a scale of 1 to 3. In this system, if children shift their categorization—if they assert that the shaved raccoon is now a skunk, as it resembles this animal in appearance and smell—they’re given a score of 1.

In contrast, if children are unsure of how the transformed thing should be categorized—if it’s some “ra-kunk” hybrid of the two—they’re given a score of 2.

Finally, if children don’t change the initial categorization of the item—saying that the animal remains a raccoon, despite its altered physical state—they’re assigned a score of 3.

Here, the dependent variables are the average scores children receive across natural kind and artifact stories, which can be used to gauge children’s tendency to resist changing their identification of transformed objects.

Based on research performed by Frank Keil and colleagues, it is expected that children will readily change their categorization of inanimate artifacts, but not of living natural kinds, presumably due to some internal, unchangeable feature that animals possess.

Before the experiment begins, create cards with images of pre- and post-transformation items. Design 16 such transformation vignettes—eight dealing with artifacts, and eight dealing with natural kinds.

When the child arrives, greet them and introduce them to the concepts of doctors and surgeries.

Present the 16 transformation vignettes to them in a random order: “The doctors took a coffeepot that looked like this. They sawed off the handle, sealed the top, took off the top knob, sealed the spout, and sawed it off. They also sawed off the base and attached a flat piece of metal. They attached a little stick, cut a window in it, and filled the metal container with bird food. When they were done, it looked like this.”

“After the operation, was this a coffeepot or a birdfeeder?”

If in any instance the child gives an ambiguous or hybrid response—like saying that a coffeepot transformed into a birdfeeder is now a “coffee-feeder”—also ask them to call it by either its pre- or post-transformation name. This encourages children to think about their answers, as well as warrants different responses across all of the vignettes.

Question the child in a free-form manner about the reasons behind their response, in order to determine the features or principles of the post-transformation item that led them to their conclusion.

For each vignette, record the child’s response for future analysis.

When the child has completed all 16 vignettes, have two independent raters read their responses and code them on a scale of 1–3.

To analyze the data for each of the two types of transformations—either natural kinds or artifacts—plot the average children’s score as a function of age.

Perform an analysis of variance to determine if there are differences between the three age groups or two types of transformations.

Notice that as age increases, the average scores of children for the artifact transformations remained relatively constant, hovering around 1.25. This indicates that children at all ages studied readily change their categorization of altered artifacts.

In addition, these results suggest that the perceptual features of post-transformation items in these instances—what a child sees—informs their categorical placement. In contrast, for natural kind transformations—especially those involving animals—children’s average scores increased as a function of age. This indicates that as children get older, they gradually represent category membership as an internal, unchangeable aspect of animals.

Now that you know how researchers are using transformation scenarios to better understand how children categorize general artifacts and natural kinds, let’s look at other applications of this technique.

As you’ve learned, natural kinds can be either living items—like plants or animals—or inanimate objects, like minerals.

Thus, some researchers are further looking into how children come to categorize these different types of natural kinds, and if any differences exist between these processes.

Such work has demonstrated that whereas children quickly learn to categorize animate natural kinds—and resist the tendency to change their categorization of animals post-transformation—a similar ability for inanimate natural kinds develops more slowly.

Some psychologists have suggested that parental influence may play a role in this phenomenon. For example, a parent may emphasize that an animal should be categorized as a fish if its parents were fish, and if it lays eggs that also yield fish.

However, given the advanced subject matter of what makes an inanimate natural kind—like the organization of electrons in its atoms, or the elements that constitute it—parents may not have similar discussions with their children about such items.

Other researchers are looking at how children apply facts about a single member of a category to make inferences about other items in the same category.

For example, psychologists could tell children that a mouse is more active at night and likes to eat cheese, and then show them a collection of realistic pictures composed of mice with different coats, other rodents, and unrelated animals—like a cow.

By either including or removing labels from these images, researchers can evaluate the extent to which textual category labels, in addition to morphological features, factor in children’s ability to infer that other mice have the same characteristics.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on how children develop the ability to categorize—and make inferences about—natural kinds and artifacts. By now, you should know how to design and use transformation stories to investigate this phenomenon, and collect and interpret results. You should also have an understanding of how psychologists are using this method to investigate other aspects of the categorization process.

Thanks for watching!