각성 및 인지 부조화의 오인

English

Share

Overview

출처: 피터 멘데-시들레키 & 제이 반 바벨-뉴욕 대학교

심리학에 있는 연구의 호스트는 심리적 각성의 감정이 상대적으로 모호할 지도 모르다 건의하고, 특정 상황에서, 우리 자신의 정신 상태에 관하여 부정확한 결론을 내리기 위하여 저희를 지도할 수 있습니다. 이 작품의 대부분은 스탠리 슈박터와 제롬 싱어에 의해 수행 정액 연구에서 흐른다. 누군가가 흥분을 경험하고 명백하고 적절한 설명이없는 경우, 그들은 상황이나 사회적 맥락의 다른 측면의 관점에서 자신의 각성을 설명하려고 시도 할 수 있습니다.

예를 들어, 한 고전적인 연구에서 참가자들은 시력을 테스트하기 위해 “Suproxin”라는 약물을 받고 있다고 들었습니다. 1 실제로, 그들은 일반적으로 심리적 흥분의 감정을 증가 에피네프린의 샷을 받았다. 일부 참가자 는 약물 에 피 네 프 린 과 비슷한 부작용을 가질 것 이라고 들 었 하는 동안, 다른 부작용의 통보 되지 않았습니다., 다른 잘못 된 정보, 그리고 다른 흥분 부작용과 위약을 받았다. 참가자들은 남부 동맹과 상호 작용했는데, 이들은 기쁘게 행동하거나 화가 났습니다. 저자는 각성의 그들의 감정에 대한 설명이 없는 참가자가(예를 들면,통보되지 않은 상태)가 남부 동맹에 가장 취약하다는 것을 관찰했습니다. 즉, 이 참가자들은 남부동맹의 감정 (행복감 또는 분노)을 가장 강하게 받아들였습니다.

후속 연구는 자연 환경에서 대인 관계 매력의 도메인에이 효과를 일반화. 2 연구원은 남성 참가자가 높고 좁은 현수교 (높은 각성) 또는 더 낮고 더 안정적인 다리 (낮은 각성)를 가로 질러 걷는 매력적인 여성 실험가를 만났습니다. 참가자들이 모호한 그림을 설명하라는 질문을 받은 설문지를 작성한 후, 실험자는 자신의 전화 번호를 제공했고, 그 후 추가 질문이 있으면 전화하도록 지시받았습니다. 특히, 흥분 현수교를 가로 질러 걸어 남자는 더 성적 콘텐츠와 설명을 제공, 그들은 연구 후 실험자 호출 할 가능성이 더 높았다. 저자는 이 사람들이 다리 건너에서 여성 실험자와의 상호 작용에 이르기까지 발생하는 심리적 각성을 잘못 기인했다고 결론을 내렸고, 그 후 그녀의 흥분을 그녀를 향한 매력의 표시로 해석했습니다.

잔나와 쿠퍼 (1974)3 인지 불협화음의 연구에 이러한 원칙을 적용. 그(것)들은 인지 불협화음을 경험하는 사람들, 그러나 몇몇 다른, 외부 영향에 관하여 그들의 심리적 각성 각성귀에 기인할 수 있는 사람들은, 외부 설명의 근원이 없는 사람들에 비해 주제에 관하여 그들의 태도를 바꾸기 위하여 확률이 낮을 것이라고 예측했습니다. 이 작품은 1962년 레온 페스팅거(Leon Festinger)의 인지 불협화음에 대한 초기 연구의 전통을 따르며, 불협화음 자체가 심리적으로 자극되는 현상이며, 이는 불편함이나 긴장으로 경험할 수 있음을 시사합니다. 4

Principles

Procedure

Results

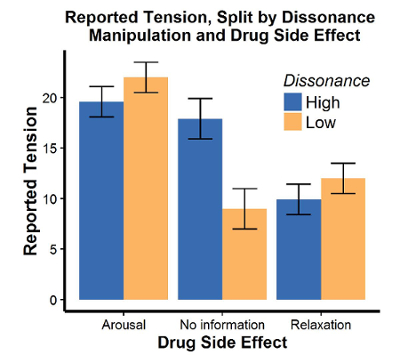

In the original investigation, the authors observed that participants’ reports of tension were influenced by the side effects that the experimenters ascribed to the drug (Figure 1). Participants in the arousal condition felt more tense than participants in the no-information condition, while participants in the relaxation condition would make them feel relaxed felt less tense than participants in the no-information condition. Moreover, within the no-information condition, participants in the high-choice condition reported feeling more tense than participants in the low-choice condition.

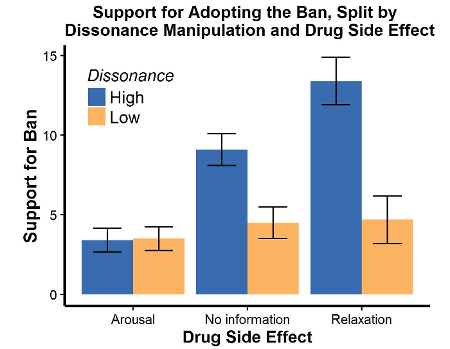

With regards to the attitude change results, the authors observed the classic dissonance result in the no-information condition: Participants in the high-choice condition showed larger changes in their attitudes than participants in the low-choice condition (Figure 2). However, in the arousal condition, there were no differences in attitude change between high- and low-choice. Conversely, in the relaxation condition, the effects of dissonance were exaggerated: Individuals in the high-choice condition showed even stronger evidence of attitude change, compared to low-choice participants.

Figure 1: Reported tension as a function of dissonance manipulation and drug side effect. Participants’ reported feelings of tension are plotted on the y-axis, as a function of both the dissonance manipulation they were exposed to and description of the drug’s side effects that they were given. Confirming the side effects manipulation, participants who were told the drug would make them feel aroused felt more tense than participants in the no-information condition, while participants who were told the drug would make them feel relaxed felt less tense than participants in the no-information condition. Moreover, within the no-information condition, participants in the high dissonance condition felt more tension than those in the low dissonance condition.

Figure 2: Support for adopting the ban as a function of dissonance manipulation and drug side effect. Participants’ support for adopting a ban on inflammatory speakers is plotted on the y-axis, as a function of both the dissonance manipulation they were exposed to and description of the drug’s side effects that they were given. The figure shows an interaction between the dissonance manipulation and the side effects ascribed to the drug. While participants who could attribute their arousal to the drug showed no support for the ban in either dissonance condition, participants in the no information condition showed stronger support for the ban in the high dissonance condition than in the low dissonance condition. Furthermore, when participants expected the drug to produce relaxation as a side effect, this effect of the high dissonance condition was even more pronounced.

Applications and Summary

Based on these results, the authors concluded that dissonance is, indeed, a psychologically arousing, drive-like mental state. As such, offering participants an external cue to ascribe their arousal to (in this case, the drug, as it was described in the arousal condition) reduced feelings of dissonance, and as a result, diminished the degree to which participants changed their attitudes. While the procedure described above has been employed here specifically as a means for studying cognitive dissonance, it could be modified to serve as a general method for inducing feelings of arousal, and more specifically, for examining the misattribution of arousal.

The overarching implication of studies like the one conducted by Zanna and Cooper in 1974 is that we are profoundly influenced by aspects of “the situation.” Why we may think that we know how we feel (and why we feel it) at any given moment, our mental states are a product of myriad external and internal factors. If you want to avoid feeling nervous before a crucial job interview, maybe avoid the (potentially) arousing cup of coffee. Conversely, perhaps taking a first date to a scary movie will cause them to misinterpret their racing heart rate as a sign of attraction.

More specifically with regards to the science of persuasion, this research suggests that psychological discomfort is a necessary condition for an individual to change their minds with respect to a given belief. Moreover, for attitude change to occur, it may be crucial to ensure that the individual is not able to attribute this discomfort to some other environmental attribute.

References

- Schachter, S., & Singer, J. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review, 69, 379-399.

- Dutton, D. G., & Aron, A. P. (1974). Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 510-517.

- Zanna, M. P., & Cooper, J. (1974). Dissonance and the pill: An attribution approach to studying the arousal properties of dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 703-709.

- Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231-259.

Transcript

We may think that we know how and why we feel a certain way at any given moment. However, mental states are a product of both internal dispositions and external situations that we are not directly aware, which— under certain circumstances—creates inconsistencies between perceptual expectations and reality.

For example, while hiking an individual approaches a high and narrow suspension bridge and must cross it. In doing so, he is psychologically aroused, even though he doesn’t realize it. Instead, he interprets his feelings of excitement in terms of other salient aspects of the situation—like meeting a woman on the other side.

In this particular setting, he misattributed his arousal as a sign of attraction towards the female rather than the true cause—the bridge-crossing. Thus, the misattribution led to attraction and his pursuit of daringly exchanging his phone number.

However, if before scheduling the hiking trip he was committed to being single, such an action would be inconsistent with his own expectations, which is an example of cognitive dissonance—a state of mental distress related to simultaneously holding contradictory beliefs. This psychological conflict produces discomfort and as a result, could cause the individual to avoid relationship situations in the future.

This video demonstrates how to manipulate principles behind the two-factor theory of emotion—that feelings are a constructed product and therefore vulnerable to misinterpretation—and cognitive dissonance to ultimately measure attitudes about a particular belief, such as banning inflammatory speakers.

In this experiment, participants think they are completing a memory recall study—one that is supposed to examine a drug’s effect—when in fact, they are being manipulated. In reality, the pill is a placebo—an external cue—to attribute their internal feelings towards when writing a counter-attitudinal essay in the second phase.

During the first phase, participants are randomly divided into three groups: two are informed of the drug’s side effects—its absorption can result in either tenseness or relaxation—while the remaining third is not given any such information.

In the second phase—dissonance manipulation—participants are further divided into one of two levels: high-choice, where they can decide whether or not to write an essay that counters their beliefs about free speech on campus; or low-choice, where they are essentially forced to write it.

All participants are instructed to write the strongest and most forceful essay that they can in support of banning inflammatory speakers from campus. Those with freedom—high-choice—are reminded that they are under no obligation to take part.

Subsequently, the following dependent variables are measured using two attitude questionnaires: In the first, participants’ report their current feelings on a scale ranging from 1 (calm) to 31 (tense).

Compared to the no-information participants, those in the arousal condition are predicted to report being more tense, whereas those in the relaxed condition are expected to be the opposite—calmer. Such findings would be consistent with the original side effects provided.

Moreover, if cognitive dissonance is arousing, participants within the high-level, no-information group are expected to report being more tense than those assigned to the low-level.

In the second survey, participants are asked about their support for the adoption of the ban, on a scale from 1 (strongly opposed) to 31 (strongly in favor). For participants in the control no-information group—who had nothing to attribute their action on the essay to—those within the high-choice level are predicted to show a bigger attitude change, agreeing with the ban, compared to the low-choice level.

In addition, participants in the arousal condition are expected to attribute their tenseness to the pill and not the essay, so their attitudes of not agreeing to the ban wouldn’t change.

On the contrary, in the relaxation condition, there would be increased cognitive dissonance with a high-choice level, yielding an even bigger change in attitudes in favor of the ban, compared to the low-choice level.

Before starting the experiment, conduct a power analysis to determine the appropriate number of participants required. Once completed, greet each one in the lab and explain the cover story: that they will participate in a study on a drug’s effect on memory processes.

In the testing room, first instruct them to partake in a recall task on the computer. Display 12 nonsense words, each for a few seconds. Afterwards, prompt them to recall as many as possible.

Following the memory test, hand the participant a glass of water and a pill. From a stack of randomly ordered assignments, provide them a consent form to look over and sign before ingesting the pill. Note that the form indicates different side effects depending on the experimental conditions.

Here, the arousal assignment indicates that a reaction of tenseness is produced. For the second group, replace tenseness with relaxation. Lastly, in the no-information condition, simply indicate the absorption time and that there are no side effects. Once signed, allow the participant to ingest the pill.

Now explain that 30 min must pass before doing the second memory test and invite them to take part in another study about opinion research. To manipulate the dissonance level, tell those randomly assigned as high-choice: “I will leave it entirely up to you to decide if you would like to participate in it, but I would be very grateful if you would.” and as low choice: “During this wait, I am going to ask you to do a small task for this opinion research experiment.”

In both conditions, explain the task: “I would like you to write the strongest, the most forceful essay that you can taking the position that inflammatory speakers should be banned from college campuses.”. Emphasize for the high choice level participants: “Remember, you are under no obligation.”. Give them 10 min to complete the essay.

After they have finished writing, ask them to rate how they feel right now on a 31-point scale ranging from calm to tense. Next, ask them how they feel about adopting a ban against inflammatory speakers on campus on another 31-point scale, from strongly opposed to strongly in favor.

Additionally, to assess the effectiveness of the choice-level, ask the participants how free they felt to decline participation in this opinion research project, again on a 31-point scale, ranging from not free at all to extremely free.

Finally, debrief participants and reinforce that the pill was a placebo and thank them for taking part in the study.

To analyze the data, compute the average reported amount of tension for each of the conditions and plot the results. Use a 2 x 3 ANOVA to confirm the findings are significant.

Feelings were induced, as expected: Regardless of choice-level, participants in the arousal condition reported feeling more tense than controls, whereas those in the relaxation group reported much lower levels, consistent with being calm.

In contrast, the effects of choice-level were only evident within the control—no-information provided—condition. Here, high-choice participants reported feeling more tense than those in the low-choice condition, reinforcing that dissonance did have an impact, manipulating arousal.

To assess attitudinal differences in supporting the ban, average the ratings and use a 2 x 3 ANOVA to confirm the findings that in the no information condition, participants in the high-choice level showed larger attitude change by agreeing with the ban. These results suggest that dissonance was affecting their behavior.

This effect of dissonance was even greater for the relaxation condition with an exaggerated agreement to the ban in the high-choice level.

However, there was no effect of dissonance in the arousal condition; that is, the high-choice level showed similar support for the ban as the low-choice level, suggesting they ascribed their arousal to the external influence of the drug, thereby reducing their feelings of dissonance and change in attitude.

Now that you are familiar with misattribution of psychological arousal and how it can be used to alter the effects of cognitive dissonance, let’s look at other real-life situations where these principles can be applied.

Based on the research on misattribution of arousal, one might want to take a first date to perform an active sport in the hope that they will misinterpret their racing heart as a sign of attraction. This strategy is used all the time in popular romantic TV shows to help build attraction between contestants.

Research also suggests that in order for an individual to change their mind with respect to a given belief, psychological discomfort is necessary. For example, to convince someone to switch to a vegetarian diet, consider offering a psychologically arousing argument based on the ethics of animal welfare.

Cognitive dissonance is created the next time that person makes a choice between a meat meal and a vegetable one. If enough psychological discomfort exists, they will choose the vegetarian feast to lessen the dissonance.

Lastly, researchers have combined functional magnetic resonance imaging with dissonance manipulation to figure out what brain regions are involved. Participants were tasked with pretending that the unpleasant MRI experience was in fact pleasant.

The anterior cingulate cortex of those who were pretending showed increased activity as compared to controls, suggesting this region is involved in processes related to cognitive dissonance.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on the misattribution of arousal and cognitive dissonance. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design and execute an experiment with manipulations of psychological feelings and opinions, how to analyze and assess the results, as well as how to apply the principles to a number of real-world situations.

Thanks for watching!