Le test Rouge : à la recherche d'un sens de soi

English

Diviser

Vue d'ensemble

Source : Laboratoires de Nicholaus mimine et Judith Danovitch — Université de Louisville

Les humains sont différents des autres animaux à bien des égards, mais une des capacités qui distingue les êtres humains est leur capacité avancée de comprendre autrui et de simuler leurs pensées et leurs sentiments, même quand les pensées et les sentiments ne sont pas alignent avec leurs propres. En termes scientifiques, ces capacités sont désignées comme la théorie de l’esprit, et cette compréhension est nécessaire pour les activités comme donner des compliments, travail en groupes, demandant des faveurs et dire des mensonges de blanc.

Les humains ne sont pas nés avec une décélération théorie de l’esprit. Un individu de comprendre qu’ils sont séparés par d’autres personnes et qu’ils ont des désirs différents et connaissances exige un sens de soi. Ainsi, en reconnaissance de soi et conscience de soi font partie des premières mesures sur la voie au développement d’une théorie de maturité d’esprit. Étudier le sens émergent de l’enfant de l’auto est compliqué, parce que le développement conceptuel de l’enfant dépasse leur maîtrise de la langue. Pour résoudre ce problème, les chercheurs emprunté les méthodes utilisées pour détecter la reconnaissance de soi chez les animaux et appliquent à jeunes enfants. Ainsi, avec un miroir et un peu de maquillage, la tâche rouge est né.

Cette vidéo montre comment les chercheurs évaluent la conscience de soi chez les enfants à différents âges.

Procédure

Résultats

In order to have enough power to see significant developmental shifts, researchers would have to test approximately 20 children per age group, not including infants dropped due to fussiness. Children who have a sense of self-recognition and self-awareness usually touch the marker on their foreheads upon seeing it in a reflection. In contrast, children who fail the test usually ignore the mark or try to touch the reflection of the mark in the mirror. Researchers also report that some children who fail the task assume they are looking at another child in the room, and they touch the mirror or look behind it to find their new friend.

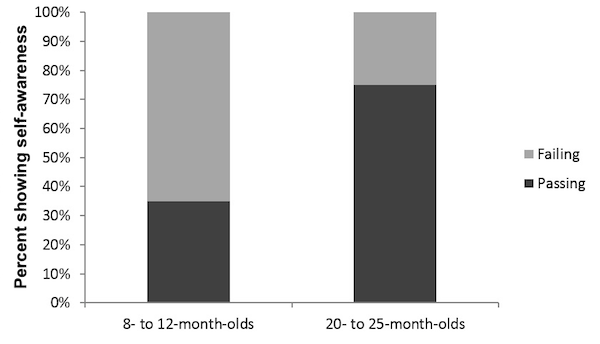

Only a small proportion of the 8- to 12-month-old infants usually pass the rouge test. The vast majority of the infants smile and play with the mirror, and many of them try to touch the mark in their reflection. In contrast, most 20- to 24-month-olds see their reflection and reach up to examine the mark on their forehead (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The proportion of children demonstrating self-awareness increases over time.

Applications and Summary

Most children begin to show the beginnings of self-awareness just before age two. At this time, they also begin to develop a rudimentary theory of mind, including the idea that different people have different preferences and desires. Building upon this basic understanding of others’ minds, children develop to represent how other people feel, leading to the development of complex comparative emotions, such as empathy, envy, and embarrassment, and pretend play, which allow them to practice their social skills even when they are alone. Children also learn to represent what other people see and know, and use this information to guide their social interactions, including knowing when and if they should try to help a friend or how to keep a surprise party a secret.2

Humans are amazing social creatures, but theory of mind is not unique to humans. Apes, elephants, dolphins, dogs, and even some birds have demonstrated the ability to recognize themselves using the rouge test. Encouraged by these findings, researchers have hypothesized that self-awareness is an important building block of social connectedness.

References

- Amsterdam, B. Mirror self-image reactions before age two. Developmental Psychobiology., 5, 297-305 (1972).

- Lewis, M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. Social cognition and the acquisition of self. New York: Plenum (1979).

Transcription

Individuals are not born with a fully developed theory of mind—the unique ability to understand others and simulate their thoughts and feelings, independently of self-desires and knowledge.

Self-recognition and self-awareness are necessary to develop a mature theory of mind. Therefore, studying a child’s emerging sense of self—like understanding one’s contribution when working amongst a group—is valuable to developmental research.

However, examining self-awareness in children is difficult because their mastery of language lags behind their conceptual development. This problem led researchers to adapt methods from animal self-recognition studies and develop the rouge task—an established technique to assess sense of self.

Using methods adapted by Beulah Amsterdam in the 1970s, this video demonstrates a simple approach for how to design and conduct the rouge test with a mirror and a bit of make-up, as well as how to analyze and interpret results on the progression of self-awareness in infants and young children before age 2.

In this experiment, children in two age groups—8- to 12-month-olds and 20- to 24-month-olds—are covertly marked on their forehead with brightly colored make-up and then observed while they look at their reflection in a mirror.

Children who only look at the mirror or who touch their reflection in the mirror fail the test, whereas those who see their reflection and touch the mark on their forehead pass.

In this case, the dependent variable is the number of children in each age group that touch the mark on their actual forehead.

It is hypothesized that the proportion of children who demonstrate self-awareness improves with age.

Before the experiment begins, verify access to a mirror large enough to clearly see the child’s face and a brightly colored and washable product, like lipstick that can be safely applied to their skin. Then, set up a video camera to capture the child’s entire reflection.

To begin, greet the parent and child and briefly inform them about the study. Then, put a small amount of lipstick on your finger.

Once inside, covertly apply lipstick onto the child’s forehead without them being able to see or feel it on their body.

Finally, video record this session: place the child in front of the mirror and observe them interacting with their reflection or physical mark.

Once the study is finished, assign two independent coders to watch the videos and designate whether each child passed or failed the test. Note that the judgments made by both coders should be compared by determining the inter-rater reliability estimate using Cohen’s kappa.

After all of the videos have been scored, generate the proportion of children that passed and failed in each age group, and use non-parametric statistics to determine if any age group differences exist.

Notice that only a small percentage of 8- to 12-month-old infants passed the test. In contrast, over 70% of 20- to 24-month-olds saw their reflection and reached up to examine the mark on their forehead, demonstrating self-awareness.

Now that you are familiar with designing a psychology experiment to investigate children’s self-awareness at a very young age, you can apply this procedure to answer additional questions regarding the normal development of children’s understanding of self and others.

As children develop self-awareness and a basic theory of mind, they begin to understand how other people feel, leading to the emergence of complex behaviors and emotions, including empathy.

Children also learn how to represent what other people know and use this information to guide their own social interactions—such as knowing if and when to keep a surprise party a secret.

In addition, children develop the ability to engage in pretend play, which allows them to practice their social skills, even when they are alone.

Before the self-concept studies were conducted in infants, Gordon Gallup showed that chimpanzees passed the rouge test. Thus, self-awareness is not unique to humans, as many social animals from elephants to birds have demonstrated the ability to relate to others in complex social situations.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s investigation into how children’s self-awareness develops over time. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design and conduct the experiment, and finally how to analyze and interpret the results.

Thanks for watching!