Mappatura Genome-wide di Drug-DNA interazioni nelle celle con COSMIC (reticolazione di piccole molecole per isolare cromatina)

Summary

Identificare gli obiettivi diretti di molecole-genoma di mira resta una sfida importante. Per capire come le molecole che legano il DNA impegnano il genoma, abbiamo sviluppato un metodo che si basa sulla reticolazione di piccole molecole per isolare cromatina (COSMIC).

Abstract

Il genoma è il bersaglio di alcuni dei chemioterapici più efficaci, ma la maggior parte di questi farmaci mancano DNA specificità di sequenza, che porta a dose-limitante tossicità e molti effetti collaterali negativi. Targeting il genoma con piccole molecole sequenza-specifiche può consentire molecole con maggiore indice terapeutico e minori effetti fuori bersaglio. N -methylpyrrole / N poliammidi -methylimidazole sono molecole che possono essere razionalmente progettati per indirizzare specifiche sequenze di DNA con squisita precisione. E a differenza di molti fattori di trascrizione naturali, poliammidi possono legarsi al DNA metilato e chromatinized senza perdita di affinità. La specificità sequenza di poliammidi è stata ampiamente studiata in vitro con l'identificazione del sito cognate (CSI) e con approcci tradizionali biochimici e biofisici, ma lo studio di poliammide vincolanti agli obiettivi genomici nelle celle rimane inafferrabile. Qui riportiamo un metodo, la reticolazione di piccole molecole per Isolate cromatina (COSMIC), che identifica i siti di legame di poliammide in tutto il genoma. COSMIC è simile a immunoprecipitazione della cromatina (ChIP), ma differisce in due modi importanti: (1) un photocrosslinker viene impiegato per consentire selettiva, cattura temporalmente controllata di poliammide eventi di legame, e (2) la maniglia affinità biotina è usato per purificare poliammide coniugati -DNA in condizioni di semi-denaturazione per diminuire DNA che non è legato covalentemente. COSMIC è una strategia generale che può essere utilizzato per rivelare gli eventi di legame genoma di poliammidi e di altri agenti chemioterapici genome-targeting.

Introduction

Le informazioni da rendere ogni cellula del corpo umano è codificato nel DNA. L'uso selettivo di tali informazioni governa il destino di una cellula. I fattori di trascrizione (TFS) sono proteine che si legano a specifiche sequenze di DNA di esprimere un particolare sottoinsieme dei geni nel genoma, e il malfunzionamento del TF è legata alla comparsa di una vasta gamma di malattie, tra cui difetti di sviluppo, il cancro e il diabete . 1,2 Siamo stati interessati a sviluppare molecole in grado di legare selettivamente al genoma e modulare reti di regolazione genica.

Poliammidi composto da N e N -methylimidazole -methylpyrrole sono molecole in grado di indirizzare il DNA con specificità e affinità che rivali fattori di trascrizione naturali. 3-6 Queste molecole si legano a sequenze specifiche nella solco minore del DNA razionalmente progettati. 4,5,7 -11 Poliammidi sono stati impiegati sia repress e attivare l'espressione di specifici gEnes. 4,12-19 Essi hanno anche interessanti antivirali e antitumorali 20-24 12,13,25-30 proprietà. Una caratteristica interessante di poliammidi è la loro capacità di accedere a sequenze di DNA che sono metilati 31,32 e avvolti intorno proteine istoniche 9,10,33.

Per misurare le specificità completi vincolanti di molecole che legano il DNA, il nostro laboratorio ha creato il metodo di identificatore del sito affine (CSI). 34-39 La presenza prevista di siti di legame sulla base di specificità in vitro (genomescapes) possono essere visualizzati sul genoma, perché la in vitro intensità vincolanti sono direttamente proporzionali alla costanti di associazione (K a). 34,35,37 Queste genomescapes permettono di percepire occupazione poliammide in tutto il genoma, ma misurare poliammide legame in cellule vive è stata una sfida. DNA è strettamente impaccato nel nucleo, che potrebbe influenzare l'accessibilità dei siti di legame. L'accessibility di queste sequenze di DNA chromatinized a poliammidi rimane un mistero.

Recentemente, molti metodi per studiare le interazioni tra piccole molecole e acidi nucleici sono emersi. 40-48 La cattura affinità chimica e sequenziamento del DNA massicciamente paralleli (chem-SEQ) è una tale tecnica. Chem-ss utilizza formaldeide per reticolare piccole molecole ad un target genomica di interesse e di un derivato biotinilato di una piccola molecola di interesse per catturare l'interazione ligando-bersaglio. 48,49

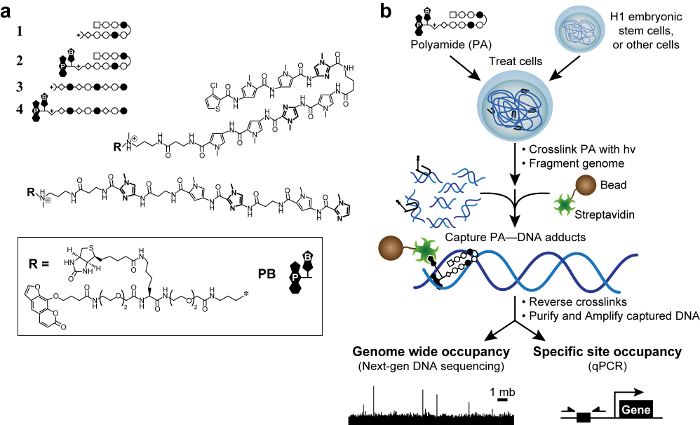

Formaldeide reticolazione porta a interazioni indirette che possono produrre dei falsi positivi. 50 Abbiamo sviluppato un nuovo metodo, la reticolazione di piccole molecole per isolare cromatina (COSMIC), 51 con un photocrosslinker per eliminare questi cosiddetti picchi "fantasma". 50 Per iniziare, abbiamo progettato e sintetizzato derivati trifunzionali di poliammidi. Queste molecole contenevano una pol-legame al DNAyamide, un photocrosslinker (psoralen), e una maniglia di affinità (biotina, Figura 1). Con poliammidi trifunzionali, possiamo covalente di catturare le interazioni in poliammide-DNA con irradiazione UV 365 nm, una lunghezza d'onda che non danneggia il DNA o indurre non psoraleni a base di reticolazione. 51 Successivamente, frammentare il genoma e purificare il DNA catturato sotto severe, semi condizioni -denaturing per diminuire DNA che non è legato covalentemente. Quindi noi consideriamo COSMIC come metodo correlate a chem-seq, ma con una lettura più diretta di DNA targeting. È importante sottolineare che i deboli (K 10 3 -10 4 M -1) affinità di psoraleni per il DNA non rilevabile poliammide impatto specificità. 51,52 I frammenti di DNA arricchito possono essere analizzati da una delle polimerasi quantitativa reazione a catena 51 (COSMIC-qPCR) o per sequenziamento di prossima generazione 53 (COSMIC-ss). Questi dati consentono un design imparziale genoma-guidata di ligandi che l'Interagire con loro loci genomici desiderato e minimizzare gli effetti fuori bersaglio.

Figura 1. poliammidi bioattivi e schema cosmico. (A) Hairpin poliammidi 1-2 bersaglio la sequenza del DNA 5'-WACGTW-3 '. Poliammidi lineari 3-4 bersaglio 5'-AAGAAGAAG-3 '. Anelli di N-metilimidazolo sono in grassetto per chiarezza. Cerchi aperti e pieni rappresentano N -methylpyrrole e N -methylimidazole rispettivamente. Square rappresenta 3 clorotiofene, e diamanti rappresentano β-alanina. Psoraleni e biotina sono indicati con P e B, rispettivamente. (B) schema cosmico. Le cellule vengono trattate con derivati trifunzionali di poliammidi. Dopo la reticolazione con irradiazione UV 365 nm, le cellule sono lDNA genomico ysed e viene tagliata. Sfere magnetiche rivestite di streptavidina vengono aggiunti per catturare addotti poliammide-DNA. Il DNA viene rilasciato e può essere analizzato mediante PCR quantitativa (qPCR) o sequenziamento di prossima generazione (NGS). Clicca qui per vedere una versione più grande di questa figura.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

One of the primary challenges with conventional ChIP is the identification of suitable antibodies. ChIP depends heavily upon the quality of the antibody, and most commercial antibodies are unacceptable for ChIP. In fact, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) consortium found only 20% of commercial antibodies to be suitable for ChIP assays.50 With COSMIC, antibodies are replaced by streptavidin. Because polyamides are functionalized with biotin, streptavidin is used in place of an antibody to capture polyam…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Ansari lab and Prof. Parameswaran Ramanathan for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants CA133508 and HL099773, the H. I. Romnes faculty fellowship, and the W. M. Keck Medical Research Award to A.Z.A. G.S.E. was supported by a Peterson Fellowship from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biosciences Training Grant NIH T32 GM07215. A.E. was supported by the Morgridge Graduate Fellowship and the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center Fellowship, and D.B. was supported by the NSEC grant from NSF.

Materials

| Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) | any source | ||

| Benzamidine | any source | ||

| Pepstatin | any source | ||

| Proteinase K | any source | ||

| Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 | Life Technologies | 65001 | |

| PBS, pH 7.4 | Life Technologies | 10010-023 | Other sources can be used |

| StemPro® Accutase® Cell Dissociation Reagent | Life Technologies | A1110501 | |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | 28104 | We have tried other manufacturers of DNA columns with success. |

| TruSeq ChIP Sample Prep Kit | Illumina | IP-202-1012 | This Kit can be used to prepare COSMIC DNA for next-generation sequencing |

| Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix | BD Biosciences | 356231 | Used to coat plates in order to grow H1 ESCs |

| pH paper | any source | ||

| amber microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| pyrex filter | any source | Pyrex baking dishes are suitable | |

| qPCR master mix | any source | ||

| RNase | any source | ||

| HCl (6 N) | any source | ||

| 10-cm tissue culture dishes | any source | ||

| Serological pipettes | any source | ||

| Pasteur pipettes | any source | ||

| Pipette tips | any source | ||

| 15-mL conical tubes | any source | ||

| centrifuge | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge | any source | ||

| nutator | any source | ||

| Magnetic separation rack | any source | ||

| UV source | CalSun | B001BH0A1A | Other UV sources can be used, but crosslinking time must be optimized empirically |

| Misonix Sonicator | Qsonica | S4000 with 431C1 cup horn | Other sonicators can be used, but sonication conditions must be optimized empirically |

| Humidified CO2 incubator | any source | ||

| Biological safety cabinet with vacuum outlet | any source |

Referências

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional Regulation and Its Misregulation in Disease. Cell. 152, 1237-1251 (2013).

- Vaquerizas, J. M., Kummerfeld, S. K., Teichmann, S. A., Luscombe, N. M. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 10, 252-263 (2009).

- Meier, J. L., Yu, A. S., Korf, I., Segal, D. J., Dervan, P. B. Guiding the Design of Synthetic DNA-Binding Molecules with Massively Parallel Sequencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17814-17822 (2012).

- Dervan, P. B. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 2215-2235 (2001).

- Wemmer, D. E., Dervan, P. B. Targeting the minor groove of DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 355-361 (1997).

- Eguchi, A., Lee, G. O., Wan, F., Erwin, G. S., Ansari, A. Z. Controlling gene networks and cell fate with precision-targeted DNA-binding proteins and small-molecule-based genome readers. Biochem. J. 462, 397-413 (2014).

- Mrksich, M., et al. Antiparallel side-by-side dimeric motif for sequence-specific recognition in the minor groove of DNA by the designed peptide 1-methylimidazole-2-carboxamide netropsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 89, 7586-7590 (1992).

- Edayathumangalam, R. S., Weyermann, P., Gottesfeld, J. M., Dervan, P. B., Luger, K. Molecular recognition of the nucleosomal “supergroove”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 6864-6869 (2004).

- Suto, R. K., et al. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 371-380 (2003).

- Gottesfeld, J. M., et al. Sequence-specific Recognition of DNA in the Nucleosome by Pyrrole-Imidazole Polyamides. J. Mol. Biol. 309, 615-629 (2001).

- Chenoweth, D. M., Dervan, P. B. Structural Basis for Cyclic Py-Im Polyamide Allosteric Inhibition of Nuclear Receptor Binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14521-14529 (2010).

- Raskatov, J. A., et al. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription using programmable DNA minor groove binders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1023-1028 (2012).

- Yang, F., et al. Antitumor activity of a pyrrole-imidazole polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1863-1868 (2013).

- Mapp, A. K., Ansari, A. Z., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Activation of gene expression by small molecule transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3930-3935 (2000).

- Ansari, A. Z., Mapp, A. K., Nguyen, D. H., Dervan, P. B., Ptashne, M. Towards a minimal motif for artificial transcriptional activators. Chem. Biol. 8, 583-592 (2001).

- Arora, P. S., Ansari, A. Z., Best, T. P., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Design of artificial transcriptional activators with rigid poly-L-proline linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13067-13071 (2002).

- Nickols, N. G., Jacobs, C. S., Farkas, M. E., Dervan, P. B. Modulating Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription by Disrupting the HIF-1–DNA Interface. ACS Chemical Biology. 2, 561-571 (2007).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. A synthetic small molecule for rapid induction of multiple pluripotency genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2, 544 (2012).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. Synthetic Small Molecules for Epigenetic Activation of Pluripotency Genes in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts. Chem Bio Chem. 12, 2822-2828 (2011).

- He, G., et al. Binding studies of a large antiviral polyamide to a natural HPV sequence. Biochimie. 102, 83-91 (2014).

- Edwards, T. G., Vidmar, T. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. DNA Damage Repair Genes Controlling Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Episome Levels under Conditions of Stability and Extreme Instability. PLoS ONE. 8, e75406 (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., Helmus, M. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. HPV Episome Stability is Reduced by Aphidicolin and Controlled by DNA Damage Response Pathways. Journal of Virology. , (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., et al. HPV episome levels are potently decreased by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Antiviral Res. 91, 177-186 (2011).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription in human cells by synthetic DNA-binding ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12890-12895 (1998).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Arresting Cancer Proliferation by Small-Molecule Gene Regulation. Chem. Biol. 11, 1583-1594 (2004).

- Nickols, N. G., et al. Activity of a Py–Im Polyamide Targeted to the Estrogen Response Element. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 12, 675-684 (2013).

- Raskatov, J. A., Puckett, J. W., Dervan, P. B. A C-14 labeled Py–Im polyamide localizes to a subcutaneous prostate cancer tumor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 4371-4375 (2014).

- Jespersen, C., et al. Chromatin structure determines accessibility of a hairpin polyamide–chlorambucil conjugate at histone H4 genes in pancreatic cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 4068-4071 (2012).

- Chou, C. J., et al. Small molecules targeting histone H4 as potential therapeutics for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 7, 769-778 (2008).

- Nickols, N. G., Dervan, P. B. Suppression of androgen receptor-mediated gene expression by a sequence-specific DNA-binding polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10418-10423 (2007).

- Minoshima, M., Bando, T., Sasaki, S., Fujimoto, J., Sugiyama, H. Pyrrole-imidazole hairpin polyamides with high affinity at 5CGCG3 DNA sequence; influence of cytosine methylation on binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2889-2894 (2008).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Fabrication of duplex DNA microarrays incorporating methyl-5-cytosine. Lab on a Chip. 12, 376-380 (2012).

- Dudouet, B., et al. Accessibility of nuclear chromatin by DNA binding polyamides. Chem. Biol. 10, 859-867 (2003).

- Carlson, C. D., et al. Specificity landscapes of DNA binding molecules elucidate biological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4544-4549 (2010).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Defining the sequence-recognition profile of DNA-binding molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 867-872 (2006).

- Tietjen, J. R., Donato, L. J., Bhimisaria, D., Ansari, A. Z., Voigt, C. Chapter One – Sequence-Specificity and Energy Landscapes of DNA-Binding Molecules. Methods Enzymol. 497, 3-30 (2011).

- Puckett, J. W., et al. Quantitative microarray profiling of DNA-binding molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12310-12319 (2007).

- Keles, S., Warren, C. L., Carlson, C. D., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-Tree: a regression tree approach for modeling binding properties of DNA-binding molecules based on cognate site identification (CSI) data. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3171-3184 (2008).

- Hauschild, K. E., Stover, J. S., Boger, D. L., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-FID: High throughput label-free detection of DNA binding molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 3779-3782 (2009).

- Lee, M., Roldan, M. C., Haskell, M. K., McAdam, S. R., Hartley, J. A. . In vitro Photoinduced Cytotoxicity and DNA Binding Properties of Psoralen and Coumarin Conjugates of Netropsin Analogs: DNA Sequence-Directed Alkylation and Cross-Link. 37, 1208-1213 (1994).

- Wurtz, N. R., Dervan, P. B. Sequence specific alkylation of DNA by hairpin pyrrole–imidazole polyamide conjugates. Chem. Biol. 7, 153-161 (2000).

- Tung, S. -. Y., Hong, J. -. Y., Walz, T., Moazed, D., Liou, G. -. G. Chromatin affinity-precipitation using a small metabolic molecule: its application to analysis of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 641-650 (2012).

- Rodriguez, R., Miller, K. M. Unravelling the genomic targets of small molecules using high-throughput sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 15, 783-796 (2014).

- Guan, L., Disney, M. D. Covalent Small-Molecule–RNA Complex Formation Enables Cellular Profiling of Small-Molecule–RNA Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10010-10013 (2013).

- White, J. D., et al. Picazoplatin, an Azide-Containing Platinum(II) Derivative for Target Analysis by Click Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11680-11683 (2013).

- Rodriguez, R., et al. Small-molecule–induced DNA damage identifies alternative DNA structures in human genes. Nat Chem Biol. 8, 301-310 (2012).

- Bando, T., Sugiyama, H. Synthesis and Biological Properties of Sequence-Specific DNA-Alkylating Pyrrole−Imidazole Polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 935-944 (2006).

- Anders, L., et al. Genome-wide localization of small molecules. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 92-96 (2014).

- Jin, C., et al. Chem-seq permits identification of genomic targets of drugs against androgen receptor regulation selected by functional phenotypic screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9235-9240 (2014).

- Landt, S. G., et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Research. 22, 1813-1831 (2012).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Eguchi, A., Ansari, A. Z. Mapping Polyamide–DNA Interactions in Human Cells Reveals a New Design Strategy for Effective Targeting of Genomic Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10124-10128 (2014).

- Hyde, J. E., Hearst, J. E. Binding of psoralen derivatives to DNA and chromatin: influence of the ionic environment on dark binding and photoreactivity. Bioquímica. 17, 1251-1257 (1978).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Rodríguez-Martínez, J. A., Grieshop, M. P., Ansari, A. Z. Genome-wide localization of polyamide-based genome readers reveals sequence-based binding to repressive heterochromatin. In preparation. , (2015).

- Chen, G., et al. Chemically defined conditions for human iPSC derivation and culture. Nat Meth. 8, 424-429 (2011).

- Deliard, S., Zhao, J., Xia, Q., Grant, S. F. A. Generation of High Quality Chromatin Immunoprecipitation DNA Template for High-throughput Sequencing (ChIP-seq). J Vis Exp. (74), e50286 (2013).

- Shi, Y. B., Spielmann, H. P., Hearst, J. E. Base-catalyzed reversal of a psoralen-DNA cross-link. Bioquímica. 27, 5174-5178 (1988).

- Kumaresan, K. R., Hang, B., Lambert, M. W. Human Endonucleolytic Incision of DNA 3′ and 5′ to a Site-directed Psoralen Monoadduct and Interstrand. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30709-30716 (1995).

- Cimino, G. D., Shi, Y. B., Hearst, J. E. Wavelength dependence for the photoreversal of a psoralen-DNA crosslink. Bioquímica. 25, 3013-3020 (1986).

- Heinz, S., et al. Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Mol. Cell. 38, 576-589 (2010).

- Zhang, Y., et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

- Kharchenko, P. V., Tolstorukov, M. Y., Park, P. J. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotech. 26, 1351-1359 (2008).

- Diamandis, E. P., Christopoulos, T. K. The biotin-(strept)avidin system: principles and applications in biotechnology. Clin. Chem. 37, 625-636 (1991).

- Martinson, H. G., True, R. J. On the mechanism of nucleosome unfolding. Bioquímica. 18, 1089-1094 (1979).

- Gloss, L. M., Placek, B. J. The Effect of Salts on the Stability of the H2A−H2B Histone Dimer. Bioquímica. 41, 14951-14959 (2002).

- Jackson, V. Formaldehyde Cross-Linking for Studying Nucleosomal Dynamics. Methods. 17, 125-139 (1999).

- Kasinathan, S., Orsi, G. A., Zentner, G. E., Ahmad, K., Henikoff, S. High-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites on native chromatin. Nat Meth. 11, 203-209 (2014).

- Teytelman, L., Thurtle, D. M., Rine, J., van Oudenaarden, A. Highly expressed loci are vulnerable to misleading ChIP localization of multiple unrelated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18602-18607 (2013).

- . Phantompeakqualtools home page Available from: https://www.encodeproject.org/software/phantompeakqualtools/ (2010)

- Wang, D., Lippard, S. J. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 4, 307-320 (2005).

- Hurley, L. H. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2, 188-200 (2002).