Genomweite Kartierung der Drug-DNA-Wechselwirkungen in Zellen mit COSMIC (Vernetzung von kleinen Molekülen, um Chromatin isolieren)

Summary

Die Ermittlung der direkten Ziele der Genom-Targeting-Moleküle vor eine große Herausforderung. Zu verstehen, wie DNA-bindende Moleküle greifen das Erbgut, eine Methode, die auf die Vernetzung von kleinen Molekülen beruht, um Chromatin zu isolieren (COSMIC) entwickelten wir.

Abstract

Das Genom ist das Ziel von einigen der wirksamsten Chemotherapeutika, aber die meisten dieser Medikamente fehlt DNA-Sequenzspezifität, die dosislimitierende Toxizität und viele unerwünschte Nebenwirkungen führt. Targeting des Genoms mit sequenzspezifischen kleine Moleküle können Moleküle mit einem erhöhten therapeutischen Index und weniger Nebeneffekte zu ermöglichen. N -methylpyrrole / N-Methylimidazol Polyamide sind Moleküle, die rational gestaltet werden kann, um spezifische DNA-Sequenzen mit vorzüglicher Präzision abzuzielen. Und im Gegensatz zu den meisten natürlichen Transkriptionsfaktoren, Polyamide können methylierte und chromatinized DNA ohne einen Verlust der Affinität binden. Die Sequenzspezifität der Polyamide wurde ausgiebig in vitro mit zugehörigen Standort-Identifizierung (CSI), die mit traditionellem biochemische und biophysikalische Methoden untersucht, aber die Untersuchung der Bindung an Polyamid genomische Ziele in Zellen weiter Ferne. Eine Methode Wir berichten hier, um die Vernetzung von kleinen Molekülen isolate Chromatin (COSMIC), dass identifiziert Polyamid-Bindungsstellen in das Genom. KOSMISCHER ähnelt Chromatinimmunpräzipitation (Chip), unterscheidet sich jedoch in zwei wichtigen Punkten: (1) ein Photovernetzungsmittel verwendet wird, um selektiv, zeitlich gesteuerte Abscheidung von Polyamid Bindungsereignisse, und (2) das Biotin-Affinität Griff verwendet wird, um Polyamid reinigen Freigabe -DNA-Konjugate unter semi-denaturierenden Bedingungen an DNA, die nicht-kovalent gebunden ist verringern. COSMIC ist eine allgemeine Strategie, die verwendet werden können, um die genomweite Bindungsereignisse von Polyamiden und anderen Genom-Targeting-Chemotherapeutika zu offenbaren.

Introduction

Die Informationen, um jede Zelle im menschlichen Körper in DNA kodiert. Die selektive Verwendung dieser Informationen regelt das Schicksal einer Zelle. Transkriptionsfaktoren (TF) sind Proteine, die an spezifische DNA-Sequenzen binden, um eine bestimmte Untergruppe der Gene im Genom zu exprimieren, und die Fehlfunktion des TFs ist mit dem Auftreten von einer Vielzahl von Krankheiten in Verbindung gebracht, einschließlich Entwicklungsdefekten, Krebs und Diabetes . 1,2 Wir sind daran interessiert, Moleküle, die wahlweise mit dem Genom binden und modulieren Genregulationsnetzwerken können.

Polyamide N -methylpyrrole komponiert und N-Methylimidazol rational entworfene Moleküle, die DNA mit Spezifitäten und Affinitäten, die rivalisierenden natürlichen Transkriptionsfaktoren. 3-6 Diese Moleküle auf bestimmte Sequenzen in der kleinen Furche der DNA binden zielen können. 4,5,7 -11 Polyamide haben sowohl repress beschäftigt und die Expression spezifischer g aktivierenenen. 4,12-19 Sie haben auch interessante antivirale 20-24 und Anti-Krebs-12,13,25-30 Eigenschaften. Ein attraktives Merkmal der Polyamide ist ihre Fähigkeit, DNA-Sequenzen, die methyliert 31,32 sind und um Histon-Proteine gewickelt 9,10,33 zuzugreifen.

Um die umfassende Bindungsspezifitäten von DNA-bindenden Moleküle zu messen, erstellt unser Labor die verwandten Standortkennung (CSI) Methode. 34-39 Die vorhergesagte Auftreten von Bindungsstellen auf Basis von in-vitro-Spezifitäten (genomescapes) können auf dem Genom angezeigt werden, weil der In-vitro-Bindungsintensität direkt proportional zur Assoziationskonstanten sind (K a). 34,35,37 Diese genomescapes Einblick in Polyamid Belegung über das Genom aber Messpolyamidbindung in lebenden Zellen eine Herausforderung gewesen. DNA wird fest in den Zellkern, die die Zugänglichkeit der Bindungsstellen beeinflussen könnten verpackt. Das accessibility dieser chromatinized DNA-Sequenzen zu Polyamiden, bleibt ein Rätsel.

In jüngster Zeit viele Methoden, um Interaktionen zwischen kleinen Molekülen und Nukleinsäuren entstanden studieren. 40-48 Die chemische Affinitätseinfangen massiv-parallelen DNA-Sequenzierung (Chem-seq) ist eine solche Technik. Chem-seq verwendet Formaldehyd, kleine Moleküle zu einer genomischen Ziel von Interesse und eines biotinylierten Derivats von einem kleinen Molekül von Interesse zu vernetzen, um den Liganden-Target-Wechselwirkung aufzunehmen. 48,49

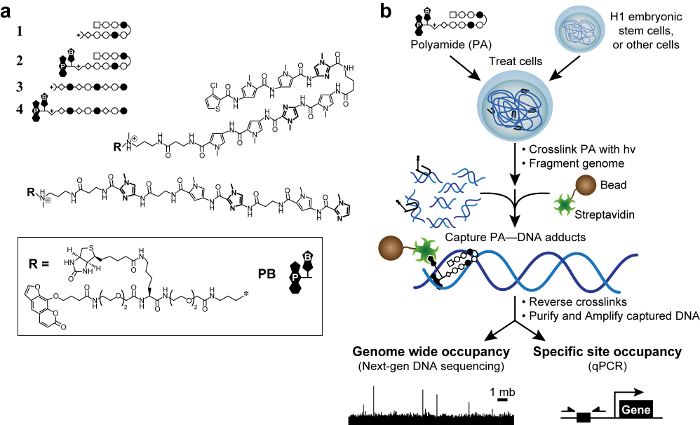

Formaldehyd-Vernetzung führt zu einer indirekten Wechselwirkungen, Fehlalarme zu erzeugen können. 50 Wir entwickelten eine neue Methode, die Vernetzung von kleinen Molekülen, um Chromatin (COSMIC), 51 mit einem Photovernetzungsmittel zu isolieren, um diese so genannte "Phantom" Spitzen zu beseitigen. 50 zu beginnen, wir entworfen und synthetisiert trifunktionellen Derivate von Polyamiden. Diese Moleküle enthalten eine DNA-Bindungs polyamide ein Photovernetzer (Psoralen) und eine Affinität Griff (Biotin, Abbildung 1). Mit trifunktionalen Polyamide, können wir kovalent erfassen Polyamid-DNA Wechselwirkungen mit 365 nm UV-Bestrahlung, einer Wellenlänge, die nicht DNA schädigt oder zu veranlassen nicht Psoralen-basierte Vernetzung. 51 Als nächstes wir Fragment des Genoms und zur Reinigung des aufgenommenen DNA unter stringenten, halb -denaturing Bedingungen an DNA, die nicht-kovalent gebunden ist verringern. So sehen wir COSMIC als Methode zur chem-seq verwandt, aber mit einer mehr direkte Auslesen der DNA-Targeting. Wichtig ist, dass die schwache (K a 10 3 bis 10 4 M -1) Affinität von Psoralen für die DNA nicht nachweisbar Auswirkungen Polyamid-Spezifität. 51,52 Die angereicherten DNA-Fragmente kann entweder quantitative Polymerase-Kettenreaktion 51 analysiert werden (COSMIC-qPCR) oder mit der nächsten Generation Sequenzierung 53 (COSMIC-seq). Diese Daten ermöglichen eine unvoreingenommene, Genom-geführte Design von Liganden interwirken mit ihren gewünschten genomischen Loci und minimieren Nebeneffekte.

Abbildung 1. Bioactive Polyamide und COSMIC Schema. (A) Hairpin Polyamiden 1-2 Target die DNA-Sequenz 5'-WACGTW-3 '. Linearen Polyamiden 3-4 Ziel 5'-AAGAAGAAG-3 '. Ringe der N-Methylimidazol zur Klarheit fett. Offene und gefüllte Kreise stellen N -methylpyrrole und N-Methylimidazol auf. Platz für 3-Chlorthiophen und Rauten stellen β-Alanin. Psoralen und Biotin sind von P und B bezeichnet sind. (B) COSMIC Schema. Zellen mit trifunktionellen Derivate von Polyamiden behandelt. Nach der Vernetzung mit einer 365 nm UV-Bestrahlung, Zellen lysed und genomische DNA geschert. Streptavidin-beschichteten magnetischen Kügelchen zugegeben werden, um Polyamid-DNA-Addukte zu erfassen. Die DNA wird freigesetzt und kann durch quantitative PCR (qPCR) oder mit der nächsten Generation Sequencing (NGS) analysiert werden. Bitte klicken Sie hier, um eine größere Version dieser Figur zu sehen.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

One of the primary challenges with conventional ChIP is the identification of suitable antibodies. ChIP depends heavily upon the quality of the antibody, and most commercial antibodies are unacceptable for ChIP. In fact, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) consortium found only 20% of commercial antibodies to be suitable for ChIP assays.50 With COSMIC, antibodies are replaced by streptavidin. Because polyamides are functionalized with biotin, streptavidin is used in place of an antibody to capture polyam…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Ansari lab and Prof. Parameswaran Ramanathan for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants CA133508 and HL099773, the H. I. Romnes faculty fellowship, and the W. M. Keck Medical Research Award to A.Z.A. G.S.E. was supported by a Peterson Fellowship from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biosciences Training Grant NIH T32 GM07215. A.E. was supported by the Morgridge Graduate Fellowship and the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center Fellowship, and D.B. was supported by the NSEC grant from NSF.

Materials

| Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) | any source | ||

| Benzamidine | any source | ||

| Pepstatin | any source | ||

| Proteinase K | any source | ||

| Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 | Life Technologies | 65001 | |

| PBS, pH 7.4 | Life Technologies | 10010-023 | Other sources can be used |

| StemPro® Accutase® Cell Dissociation Reagent | Life Technologies | A1110501 | |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | 28104 | We have tried other manufacturers of DNA columns with success. |

| TruSeq ChIP Sample Prep Kit | Illumina | IP-202-1012 | This Kit can be used to prepare COSMIC DNA for next-generation sequencing |

| Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix | BD Biosciences | 356231 | Used to coat plates in order to grow H1 ESCs |

| pH paper | any source | ||

| amber microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge tubes | any source | ||

| pyrex filter | any source | Pyrex baking dishes are suitable | |

| qPCR master mix | any source | ||

| RNase | any source | ||

| HCl (6 N) | any source | ||

| 10-cm tissue culture dishes | any source | ||

| Serological pipettes | any source | ||

| Pasteur pipettes | any source | ||

| Pipette tips | any source | ||

| 15-mL conical tubes | any source | ||

| centrifuge | any source | ||

| microcentrifuge | any source | ||

| nutator | any source | ||

| Magnetic separation rack | any source | ||

| UV source | CalSun | B001BH0A1A | Other UV sources can be used, but crosslinking time must be optimized empirically |

| Misonix Sonicator | Qsonica | S4000 with 431C1 cup horn | Other sonicators can be used, but sonication conditions must be optimized empirically |

| Humidified CO2 incubator | any source | ||

| Biological safety cabinet with vacuum outlet | any source |

Referências

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional Regulation and Its Misregulation in Disease. Cell. 152, 1237-1251 (2013).

- Vaquerizas, J. M., Kummerfeld, S. K., Teichmann, S. A., Luscombe, N. M. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 10, 252-263 (2009).

- Meier, J. L., Yu, A. S., Korf, I., Segal, D. J., Dervan, P. B. Guiding the Design of Synthetic DNA-Binding Molecules with Massively Parallel Sequencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17814-17822 (2012).

- Dervan, P. B. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 2215-2235 (2001).

- Wemmer, D. E., Dervan, P. B. Targeting the minor groove of DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 355-361 (1997).

- Eguchi, A., Lee, G. O., Wan, F., Erwin, G. S., Ansari, A. Z. Controlling gene networks and cell fate with precision-targeted DNA-binding proteins and small-molecule-based genome readers. Biochem. J. 462, 397-413 (2014).

- Mrksich, M., et al. Antiparallel side-by-side dimeric motif for sequence-specific recognition in the minor groove of DNA by the designed peptide 1-methylimidazole-2-carboxamide netropsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 89, 7586-7590 (1992).

- Edayathumangalam, R. S., Weyermann, P., Gottesfeld, J. M., Dervan, P. B., Luger, K. Molecular recognition of the nucleosomal “supergroove”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 6864-6869 (2004).

- Suto, R. K., et al. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 371-380 (2003).

- Gottesfeld, J. M., et al. Sequence-specific Recognition of DNA in the Nucleosome by Pyrrole-Imidazole Polyamides. J. Mol. Biol. 309, 615-629 (2001).

- Chenoweth, D. M., Dervan, P. B. Structural Basis for Cyclic Py-Im Polyamide Allosteric Inhibition of Nuclear Receptor Binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14521-14529 (2010).

- Raskatov, J. A., et al. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription using programmable DNA minor groove binders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1023-1028 (2012).

- Yang, F., et al. Antitumor activity of a pyrrole-imidazole polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1863-1868 (2013).

- Mapp, A. K., Ansari, A. Z., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Activation of gene expression by small molecule transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3930-3935 (2000).

- Ansari, A. Z., Mapp, A. K., Nguyen, D. H., Dervan, P. B., Ptashne, M. Towards a minimal motif for artificial transcriptional activators. Chem. Biol. 8, 583-592 (2001).

- Arora, P. S., Ansari, A. Z., Best, T. P., Ptashne, M., Dervan, P. B. Design of artificial transcriptional activators with rigid poly-L-proline linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13067-13071 (2002).

- Nickols, N. G., Jacobs, C. S., Farkas, M. E., Dervan, P. B. Modulating Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription by Disrupting the HIF-1–DNA Interface. ACS Chemical Biology. 2, 561-571 (2007).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. A synthetic small molecule for rapid induction of multiple pluripotency genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2, 544 (2012).

- Pandian, G. N., et al. Synthetic Small Molecules for Epigenetic Activation of Pluripotency Genes in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts. Chem Bio Chem. 12, 2822-2828 (2011).

- He, G., et al. Binding studies of a large antiviral polyamide to a natural HPV sequence. Biochimie. 102, 83-91 (2014).

- Edwards, T. G., Vidmar, T. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. DNA Damage Repair Genes Controlling Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Episome Levels under Conditions of Stability and Extreme Instability. PLoS ONE. 8, e75406 (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., Helmus, M. J., Koeller, K., Bashkin, J. K., Fisher, C. HPV Episome Stability is Reduced by Aphidicolin and Controlled by DNA Damage Response Pathways. Journal of Virology. , (2013).

- Edwards, T. G., et al. HPV episome levels are potently decreased by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Antiviral Res. 91, 177-186 (2011).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription in human cells by synthetic DNA-binding ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12890-12895 (1998).

- Dickinson, L. A., et al. Arresting Cancer Proliferation by Small-Molecule Gene Regulation. Chem. Biol. 11, 1583-1594 (2004).

- Nickols, N. G., et al. Activity of a Py–Im Polyamide Targeted to the Estrogen Response Element. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 12, 675-684 (2013).

- Raskatov, J. A., Puckett, J. W., Dervan, P. B. A C-14 labeled Py–Im polyamide localizes to a subcutaneous prostate cancer tumor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 4371-4375 (2014).

- Jespersen, C., et al. Chromatin structure determines accessibility of a hairpin polyamide–chlorambucil conjugate at histone H4 genes in pancreatic cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 4068-4071 (2012).

- Chou, C. J., et al. Small molecules targeting histone H4 as potential therapeutics for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 7, 769-778 (2008).

- Nickols, N. G., Dervan, P. B. Suppression of androgen receptor-mediated gene expression by a sequence-specific DNA-binding polyamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10418-10423 (2007).

- Minoshima, M., Bando, T., Sasaki, S., Fujimoto, J., Sugiyama, H. Pyrrole-imidazole hairpin polyamides with high affinity at 5CGCG3 DNA sequence; influence of cytosine methylation on binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2889-2894 (2008).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Fabrication of duplex DNA microarrays incorporating methyl-5-cytosine. Lab on a Chip. 12, 376-380 (2012).

- Dudouet, B., et al. Accessibility of nuclear chromatin by DNA binding polyamides. Chem. Biol. 10, 859-867 (2003).

- Carlson, C. D., et al. Specificity landscapes of DNA binding molecules elucidate biological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4544-4549 (2010).

- Warren, C. L., et al. Defining the sequence-recognition profile of DNA-binding molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 867-872 (2006).

- Tietjen, J. R., Donato, L. J., Bhimisaria, D., Ansari, A. Z., Voigt, C. Chapter One – Sequence-Specificity and Energy Landscapes of DNA-Binding Molecules. Methods Enzymol. 497, 3-30 (2011).

- Puckett, J. W., et al. Quantitative microarray profiling of DNA-binding molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12310-12319 (2007).

- Keles, S., Warren, C. L., Carlson, C. D., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-Tree: a regression tree approach for modeling binding properties of DNA-binding molecules based on cognate site identification (CSI) data. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3171-3184 (2008).

- Hauschild, K. E., Stover, J. S., Boger, D. L., Ansari, A. Z. CSI-FID: High throughput label-free detection of DNA binding molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 3779-3782 (2009).

- Lee, M., Roldan, M. C., Haskell, M. K., McAdam, S. R., Hartley, J. A. . In vitro Photoinduced Cytotoxicity and DNA Binding Properties of Psoralen and Coumarin Conjugates of Netropsin Analogs: DNA Sequence-Directed Alkylation and Cross-Link. 37, 1208-1213 (1994).

- Wurtz, N. R., Dervan, P. B. Sequence specific alkylation of DNA by hairpin pyrrole–imidazole polyamide conjugates. Chem. Biol. 7, 153-161 (2000).

- Tung, S. -. Y., Hong, J. -. Y., Walz, T., Moazed, D., Liou, G. -. G. Chromatin affinity-precipitation using a small metabolic molecule: its application to analysis of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 641-650 (2012).

- Rodriguez, R., Miller, K. M. Unravelling the genomic targets of small molecules using high-throughput sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 15, 783-796 (2014).

- Guan, L., Disney, M. D. Covalent Small-Molecule–RNA Complex Formation Enables Cellular Profiling of Small-Molecule–RNA Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10010-10013 (2013).

- White, J. D., et al. Picazoplatin, an Azide-Containing Platinum(II) Derivative for Target Analysis by Click Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11680-11683 (2013).

- Rodriguez, R., et al. Small-molecule–induced DNA damage identifies alternative DNA structures in human genes. Nat Chem Biol. 8, 301-310 (2012).

- Bando, T., Sugiyama, H. Synthesis and Biological Properties of Sequence-Specific DNA-Alkylating Pyrrole−Imidazole Polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 935-944 (2006).

- Anders, L., et al. Genome-wide localization of small molecules. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 92-96 (2014).

- Jin, C., et al. Chem-seq permits identification of genomic targets of drugs against androgen receptor regulation selected by functional phenotypic screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9235-9240 (2014).

- Landt, S. G., et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Research. 22, 1813-1831 (2012).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Eguchi, A., Ansari, A. Z. Mapping Polyamide–DNA Interactions in Human Cells Reveals a New Design Strategy for Effective Targeting of Genomic Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10124-10128 (2014).

- Hyde, J. E., Hearst, J. E. Binding of psoralen derivatives to DNA and chromatin: influence of the ionic environment on dark binding and photoreactivity. Bioquímica. 17, 1251-1257 (1978).

- Erwin, G. S., Bhimsaria, D., Rodríguez-Martínez, J. A., Grieshop, M. P., Ansari, A. Z. Genome-wide localization of polyamide-based genome readers reveals sequence-based binding to repressive heterochromatin. In preparation. , (2015).

- Chen, G., et al. Chemically defined conditions for human iPSC derivation and culture. Nat Meth. 8, 424-429 (2011).

- Deliard, S., Zhao, J., Xia, Q., Grant, S. F. A. Generation of High Quality Chromatin Immunoprecipitation DNA Template for High-throughput Sequencing (ChIP-seq). J Vis Exp. (74), e50286 (2013).

- Shi, Y. B., Spielmann, H. P., Hearst, J. E. Base-catalyzed reversal of a psoralen-DNA cross-link. Bioquímica. 27, 5174-5178 (1988).

- Kumaresan, K. R., Hang, B., Lambert, M. W. Human Endonucleolytic Incision of DNA 3′ and 5′ to a Site-directed Psoralen Monoadduct and Interstrand. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30709-30716 (1995).

- Cimino, G. D., Shi, Y. B., Hearst, J. E. Wavelength dependence for the photoreversal of a psoralen-DNA crosslink. Bioquímica. 25, 3013-3020 (1986).

- Heinz, S., et al. Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Mol. Cell. 38, 576-589 (2010).

- Zhang, Y., et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

- Kharchenko, P. V., Tolstorukov, M. Y., Park, P. J. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotech. 26, 1351-1359 (2008).

- Diamandis, E. P., Christopoulos, T. K. The biotin-(strept)avidin system: principles and applications in biotechnology. Clin. Chem. 37, 625-636 (1991).

- Martinson, H. G., True, R. J. On the mechanism of nucleosome unfolding. Bioquímica. 18, 1089-1094 (1979).

- Gloss, L. M., Placek, B. J. The Effect of Salts on the Stability of the H2A−H2B Histone Dimer. Bioquímica. 41, 14951-14959 (2002).

- Jackson, V. Formaldehyde Cross-Linking for Studying Nucleosomal Dynamics. Methods. 17, 125-139 (1999).

- Kasinathan, S., Orsi, G. A., Zentner, G. E., Ahmad, K., Henikoff, S. High-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites on native chromatin. Nat Meth. 11, 203-209 (2014).

- Teytelman, L., Thurtle, D. M., Rine, J., van Oudenaarden, A. Highly expressed loci are vulnerable to misleading ChIP localization of multiple unrelated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18602-18607 (2013).

- . Phantompeakqualtools home page Available from: https://www.encodeproject.org/software/phantompeakqualtools/ (2010)

- Wang, D., Lippard, S. J. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 4, 307-320 (2005).

- Hurley, L. H. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2, 188-200 (2002).