분할 뇌

English

Share

Overview

출처: 조나스 T. 카플란과 사라 I. 짐벨의 연구소 – 서던 캘리포니아 대학

뇌손상이 인지 기능에 미치는 영향에 대한 연구는 역사적으로 인지 신경 과학을 위한 가장 중요한 도구 중 하나였습니다. 뇌는 신체의 가장 잘 보호 된 부분 중 하나 이지만, 뇌의 기능에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 많은 이벤트가 있다. 혈관 문제, 종양, 퇴행성 질환, 감염, 무딘 힘 외상 및 신경 외과는 뇌 손상의 근본 원인 중 일부에 불과하며, 모두 다른 방법으로 뇌 기능에 영향을 미치는 조직 손상의 다른 패턴을 생성 할 수 있습니다.

신경 심리학의 역사는 뇌의 이해에 있는 발전을 지도한 몇몇 잘 알려진 케이스에 의해 표시됩니다. 예를 들어, 1861년 폴 브로카는 왼쪽 전두엽에 손상이 어떻게 영향을 주었는지 관찰하여 언어 장애인 실어증을 초래했습니다. 또 다른 예로, 기억 상실증 환자로부터 기억 상실증에 대한 큰 거래가 배웠습니다, 헨리 몰라이슨의 유명한 경우와 같은, 신경 심리학 문학에서 몇 년 동안 알려진 “H.M.,” 그의 현세엽 수술은 새로운 기억의 특정 종류를 형성에 깊은 적자를 주도.

초점 뇌 손상을 가진 환자의 관찰 및 테스트는 뇌의 기능에 대한 통찰력을 신경 과학을 제공했지만, 적자의 특정 특성을 밝히기 위해 테스트를 설계하는 데 세심한 주의를 기울여야합니다. 또한 뇌는 상호 연결된 뉴런의 복잡한 네트워크이기 때문에 한 뇌 부위의 손상은 손상으로부터 멀리 떨어진 지역에서 기능에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 뇌 손상이 뇌 영역 간의 연결에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 보여주기 위해이 비디오는 소위 분할 뇌의 경우를 검사합니다.

코퍼스 캘로섬은 뇌의 왼쪽과 오른쪽 반구를 연결하는 섬유의 큰 번들입니다. 그것은 두뇌에 있는 가장 큰 백색 물질 기관 중 하나 이며 쉽게 뇌의 중간선의 처진 보기에 인식 될 수 있습니다. 1960 년대에, 신경 외과 의사는 코퍼스 callosum절단이 뇌를 통해 확산 제어 할 수없는 신경 활동을 포함하는 간질의 특정 종류에 대한 성공적인 치료가 될 수 있음을 발견했다. 분할 뇌 수술을 받은 사람들은 두 반구를 외과적으로 분리하여 왼쪽과 오른쪽 반구가 더 이상 의사 소통을 할 수 없게되었습니다. 이 조건은 실험자가 좌우 반구의 기능을 독립적으로 조사하고, 상대적 능력에 대해 배우고, 그들 사이의 의사 소통의 본질에 대해 배울 수 있게 했습니다.

이 비디오는 두뇌의 두 반구 사이 다름의 몇몇을 드러내고 그 같은 단절의 몇몇 극적인 결과를 보기 위하여 분할 두뇌 환자를 시험하는 방법을 보여줍니다. 이 실험의 원래 버전은 마이클 Gazzaniga와 동료에 의해 개발되었다1, 2 나중에 다른 사람에 의해 정교했다; 3 여기에 제시 된 버전은 방법론의 최신 현대화를 통합합니다.

Procedure

Results

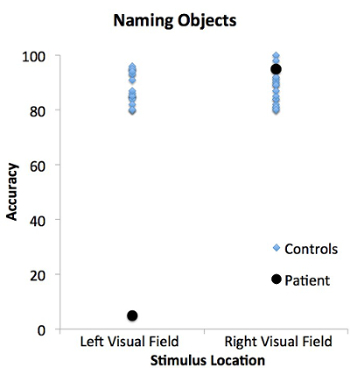

Typically, callosotomy patients exhibit an anomia for objects presented in the left visual half-field. Anomia is the inability to name objects. Objects presented to the right visual field, however, are named with high accuracy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Patient and control performance in the naming objects task for stimuli presented in the left and right visual fields. The patient (black circles) is not able to verbally name objects presented in the left visual field, but is able to name objects in the right visual field. In contrast, the control population (blue diamonds) can name objects presented in both the left and right visual fields.

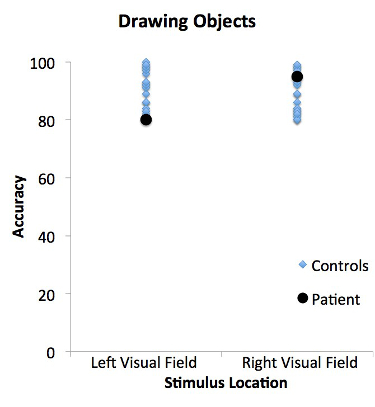

Some patients may be able to successfully draw objects presented to the left visual field, even though they cannot verbally name them (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Patient and control performance in the drawing objects task for stimuli presented in the left and right visual fields. The patient (black circles) and control population (blue diamonds) are able to draw objects presented in both the left and right visual fields. The patient's performance does not differ from matched controls.

In this case, the patient usually says they haven't seen anything. This is because the left hemisphere, which is controlling speech, has not seen the visual image. However, the right hemisphere, which has seen the object, can recognize it but is unable to generate speech. Since the right hemisphere is largely in control of the left hand, the patient is able to draw the object with the left hand. This result demonstrates a dissociation between the ability to recognize an object and the ability to verbally name an object.

The control population, with intact corpora callosa, can both name and draw objects presented in the left or right visual fields. This is because information can freely pass from one hemisphere to the other, allowing for the sharing of information between the brain regions.

Applications and Summary

The case of the split-brain patient reveals the relative specialization of the two cerebral hemispheres. Many of these specializations can also be demonstrated in healthy people with intact commissures using similar techniques. For example, people tend to recognize words faster when they are presented briefly in the right visual field compared to when they are presented in the left visual field. This experiment also shows that even when two brain regions are healthy, damage to the connections between different regions can affect behavior.

However, it is important to remember that while testing the split brain demonstrates the differences between the two cerebral hemispheres, in the intact brain, the two hemispheres are continually interacting with each other and working in concert. To isolate a stimulus to one visual field requires specialized equipment that can present stimuli very briefly and away from central fixation. Since central vision is processed by both hemispheres, and the eyes typically scan an environment, this is not a situation that is likely to be encountered in everyday life.

References

- Gazzaniga, M. S., Bogen, J. E., & Sperry, R. W. (1962). Some functional effects of sectioning the cerebral commissures in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 48, 1765-1769.

- Gazzaniga, M. S., Bogen, J. E., & Sperry, R. W. (1965). Observations on visual perception after disconnexion of the cerebral hemispheres in man. Brain, 88(2), 221-236.

- Zaidel, E., Zaidel, D., & Bogen, J. E. (1990). Testing the commussurotomy patient. In A. Boulton, G. Baker, & M. Hiscock (Eds.), Neuromethods (pp. 147-201). Clifton, NJ: Humana Press.

Transcript

Neuropsychologists study “split-brain” patients to probe the unique functions of the left and right brain hemispheres—in other words, to study lateralization—and to also investigate the nature of communication between these regions.

Primarily speaking, information from one side of the body is processed within the opposite half of the brain. In addition, each hemisphere contralaterally directs body movements.

These areas also have different cognitive strengths: the left side is typically associated with the control of language and speech, whereas the right plays a large role in processing visuospatial information—like judging the spatial arrangements of dials on a machine.

Normally, collections of neurons’ axons—referred to as nerve fiber bundles—transfer information between these hemispheres. One of the largest of such tracts is the corpus callosum.

However, this inter-hemispheric communication is interrupted in split-brain patients, whose corpora callosa have been surgically severed—a treatment sometimes used to reduce the uncontrollable neural activity characteristic of epilepsy from spreading throughout the entire brain.

Using modernizations of psychologist Michael Gazzaniga’s techniques, this video demonstrates how to test split-brain patients and assess their cognitive abilities—specifically speech production—and illustrates data collection and analysis methods.

In this experiment, patients are shown images of everyday objects and asked to verbalize the name of each item.

To achieve lateralization, patients are instructed to focus on a cross symbol in the center of a computer screen, and told to remain fixated on this shape for the duration of the experiment. Here, the cross serves as a reference point next to which visual stimuli can be shown on either the right or left.

If an image is presented on the right of the screen, it falls into the right visual field—which, perhaps counterintuitively, is processed by the left portions of both eyes. These regions then project the observed image to the left hemisphere of the brain, where it is identified.

Thus, functions of the left brain hemisphere can be assessed by showing images in the right visual field.

Similarly, a stimulus presented to the left of the cross onscreen—in the left visual field—can be used to evaluate the roles of the right hemisphere.

During the naming objects task, a total of fifty drawings, like that of a chicken, appear one at a time on a random side of the monitor—either the right or left.

Pictures are presented for less than 150 ms. As this is not enough time for a patient to move their eyes to reposition the image, it ensures that only the brain hemisphere being tested “sees” the stimulus.

After the image disappears, the patient must identify it aloud, which serves as a measure of the lateralization of verbal linguistic capability.

Here, the dependent variable is the percentage of images shown in the left and right visual fields that the patient is able to name—in other words, the accuracy of verbal identification.

Based on the previous work of Gazzaniga and others, it is expected that patients will be able to name images presented in the right visual field with high accuracy, as this information is seen by the left hemisphere—the region capable of controlling speech.

However, patients will be unable to verbally identify pictures shown in the left visual field, as this information is handled by the right brain hemisphere, which is incapable of generating language and—in split-brain patients—cannot communicate with the speech-capable left side.

If the image can’t be named—referred to as anomia—a drawing task is performed, which serves as a non-linguistic measure of stimulus knowledge.

Here, patients must create a picture of the image they were shown using the hand on the ipsilateral or same side as the tested visual field. Thus, if patients can’t verbally identify an object presented on the left of the screen, they should draw it with their left hand.

In this instance, the dependent variable is the percentage of images shown in the left and right visual fields that are accurately drawn.

It is expected that patients unable to name pictures shown on the left of the monitor will still be able to draw them—using their left hand—with high accuracy.

This is due to the fact that the right hemisphere—which controls the left arm and hand—also processes information from the left visual field. Thus, no communication is needed between the hemispheres to complete this task.

Prior to beginning the experiment, review patients’ MRI data to determine which nerve fiber bundles they are lacking. For the purpose of this demonstration, a patient in whom the entire corpus callosum has been severed is tested, and their data will be compared to those collected from control participants.

Greet the patient when they arrive, and inform them of the research procedures. In addition, assure that they have signed all appropriate consent forms.

Then, proceed to place their chin comfortably in a chinrest so that their eyes are positioned approximately 22 in. from the screen.

With the small cross displayed in the center of the screen, emphasize to the patient that they must remain fixated on this symbol, even as images flash to the left or right of it.

Proceed by showing them 50 images, each of which are presented for 150 ms, in a random order, and evenly divided between sides. After every presentation, instruct the patient to identify the object out loud: “Apple”. Record all of their responses.

If the patient cannot name the visual stimulus, ask them to draw it with the hand on the same side as the visual field in which the picture was shown. This constitutes the drawing objects task.

Make sure that the patient does not look at their hand as they are drawing, in order to maintain the initial isolation of the stimulus to one brain hemisphere.

To confirm that the patient knows the name of the stimulus when it is simultaneously presented to both fields of view, have them look down at their completed drawing and verbally identify the object it represents: “Broom”. Again, record all of the patient’s responses.

To analyze the data, first calculate the percentage of correct verbal responses across patients for stimuli presented to the left and right visual fields.

Proceed by separately compiling the percentage of correct verbal response scores for each control participant’s left and right locations.

To identify any deficits in patient behavior, compare control and patient data using a repeated-measures analysis of variance test. Repeat the analysis for all data collected from the drawing test.

Notice that while patients are typically unable to name stimuli presented to the left visual field, they can draw them—with their left hand—with a high degree of accuracy. This demonstrates a dissociation between a patient’s ability to recognize and verbally name an object.

Now that you know how to test the functions of the left and right hemispheres of split-brain patients with visual stimuli, let’s see how researchers explore and apply lateralization in other contexts.

You’ve learned that surgical separation of the two hemispheres is often used to treat patients with epilepsy, which is characterized by seizures.

As a result, many neuroscientists are looking at whether the timing of this disconnection—whether the corpus callosum is severed during childhood or adulthood—has any affect on a patient’s cognitive functions.

Importantly, such work has demonstrated that compared to adults, children experience fewer—or less severe—cognitive effects following the disconnection of the brain hemispheres, suggesting that young brains demonstrate a great degree of plasticity.

Up until now, we’ve focused on the corpus callosum as the major connection between the left and right hemispheres.

However, other nerve fiber bundles allow for communication between the sides of the brain. Among them is the anterior commissure, which has been implicated in the transfer of sensory information, like that pertaining to sight or smell.

Thus, some researchers are looking at how the disconnection of one or more of these bundles—with or without severance of the corpus callosum—affects patient behavior.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on testing split-brain patients using visual stimuli. By now, you should understand how to present images to the two visual fields, and collect and interpret data relating to the abilities of the left and right brain hemispheres. You should also know how data from split-brain patients is being used to develop better treatments for epilepsy, and understand the roles of different nerve fiber bundles in the brain.

Thanks for watching!