利用电泳迁移分析(EMSA)和筛选功能的非编码基因变异DNA的亲和沉淀试验(DAPA)

Summary

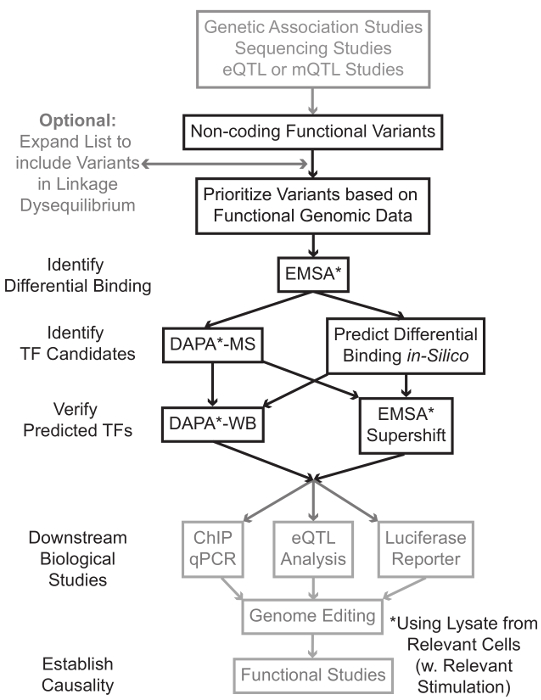

We present a strategic plan and protocol for identifying non-coding genetic variants affecting transcription factor (TF) DNA binding. A detailed experimental protocol is provided for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genotype-dependent TF DNA binding.

Abstract

Population and family-based genetic studies typically result in the identification of genetic variants that are statistically associated with a clinical disease or phenotype. For many diseases and traits, most variants are non-coding, and are thus likely to act by impacting subtle, comparatively hard to predict mechanisms controlling gene expression. Here, we describe a general strategic approach to prioritize non-coding variants, and screen them for their function. This approach involves computational prioritization using functional genomic databases followed by experimental analysis of differential binding of transcription factors (TFs) to risk and non-risk alleles. For both electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) analysis of genetic variants, a synthetic DNA oligonucleotide (oligo) is used to identify factors in the nuclear lysate of disease or phenotype-relevant cells. For EMSA, the oligonucleotides with or without bound nuclear factors (often TFs) are analyzed by non-denaturing electrophoresis on a tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gel. For DAPA, the oligonucleotides are bound to a magnetic column and the nuclear factors that specifically bind the DNA sequence are eluted and analyzed through mass spectrometry or with a reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Western blot analysis. This general approach can be widely used to study the function of non-coding genetic variants associated with any disease, trait, or phenotype.

Introduction

测序和基因分型的基础研究,包括全基因组关联分析(GWAS),候选人基因研究和深测序研究,已经确定了在统计学上与疾病,性状或表型相关的许多基因变异。相反早期预测,大多数这些变体(85-93%)的分布在非编码区,并且不改变蛋白质1,2的氨基酸序列。解释这些非编码变体的功能和确定它们连接到相关的疾病的生物学机制,特征,或表型已被证明具有挑战性3-6。我们已开发,以确定链接变体的重要中间体的表型的分子机制的一般策略 – 基因表达。这条管线是专门设计来确定的TF由遗传变异体结合的调制。这一策略结合的目的是预测的计算方法和分子生物学技术在硅片的候选变体的生物学效应,并验证这些预测凭经验( 图1)。

图1: 对于不包含在这个手稿以灰色阴影相关的详细协议的非编码基因变异步骤的分析战略方针 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

在许多情况下,通过扩大变体的列表以包括与每个统计学关联变体在高联动不平衡(LD)的所有那些开始是很重要的。 LD是在两个不同的染色体位置的等位基因的非随机关联,可以由R 2统计7被测量的量度。 R 2是林的措施卡格两个变量之间的不平衡,有两个变量之间的R 2 = 1表示完全连锁。在高LD等位基因被发现在整个人群祖先染色体上共分离。当前的基因分型阵列不包括在人类基因组中所有已知的变体。相反,他们利用了人类基因组中的LD和包括公知的变体作为代理为LD 8的一特定区域内的其它变体的一个子集。因此,在没有任何生物后果的变体可以与特定疾病,因为它是在与一个有意义的生物效应的因果变体的变体的LD相关联。在程序上,建议转换的1000基因组最新发布的项目9项变量调用文件(VCF)与PLINK 10,11,用于全基因组关联分析的开放源代码工具兼容的二进制文件。随后,LD R 2> 0.8所有其他遗传变异与每个输入遗传VAriant可确定为候选者。使用合适的参考人群该步进例如是很重要的,如果一个变种是在欧洲血统的科目,从类似的血统科目的数据应该用于LD扩展标识。

LD膨胀常常导致数十个候选变体,它是可能的,只有这些一小部分有助于疾病的机制。通常,它是不可行的实验逐一检查每个这些变体。因此,有用以利用数千公开可用功能基因组数据集作为过滤器的变体的优先次序。例如,编码财团12已经如DNA酶SEQ 13,ATAC进行数千描述转录因子的结合芯片起实验和辅因子,以及组蛋白标记在各种上下文,以及染色质辅助数据从技术-SEQ 14和FAIRE-SEQ 15。数据BASES和Web服务器如UCSC基因组浏览器16,路线图表观基因组17,蓝图表观基因组18,顺反组19,并重新映射20提供由这些和其他实验技术在广泛的细胞类型和条件产生的数据免费访问。当有太多的变体通过实验检验,这些数据可以被用来优先那些位于相关的细胞和组织类型的可能调控区之内。此外,在一个变型为特定蛋白的芯片起峰内的情况下,这些数据可以提供潜在线索作为对特定TF(S)或辅因子的结合可能影响。

接着,将所得的优先变体实验筛选,以验证预测的基因型依赖性蛋白使用EMSA 21,22结合。 EMSA测量的寡核苷酸上的非还原性TBE凝胶迁移的变化。荧光标记的寡核苷酸温育与核裂解物,以及核因子的结合将延缓在凝胶上的寡的运动。以这种方式,已经结合更多的核因子将呈现为对扫描更强的荧光信号寡。值得注意的是,EMSA不需要关于特定蛋白质的结合会受到影响的预测。

一旦变体被识别,它们位于预测的调节区之内,并且能够差动结合核因子中,采用计算的方法来预测具体TF(S),其结合它们可能会影响。我们优选使用CIS-BP 23,24,RegulomeDB 25,UniProbe 26和JASPAR 27。一旦候选人转录因子被确定,这些预测可以专门使用抗转录因子这些(EMSA-supershifts和DAPA-西部片)测试。一个EMSA-超迁移涉及增加了一个特定的TF-抗体与核裂解物和寡。阳性结果在EMSA-超迁移是再版esented如在EMSA频带的进一步转变,或带的损耗(在参考28中综述)。在互补DAPA,含有该变体和20个碱基对的侧翼核苷酸的5'-生物素化的寡核苷酸双链体与来自相关的细胞类型(多个)核裂解物温育以捕获任何核因子特异性结合的寡核苷酸。低聚双链核因子复合物是通过在一个磁列链霉微珠固定。结合的核因子直接通过洗脱29,48收集。结合预测可以然后通过使用特异于所述蛋白质的抗体的Western印迹来评估。在没有明显的预测,或过多的预测,从DAPA实验的变体拉起伏的洗脱可被发送到一个蛋白质组学芯使用质谱来识别候选转录因子的情况下,其可以随后使用验证这些先前描述的方法。

在该articl剩余即,提供了一种用于遗传变异体的EMSA和DAPA分析的详细协议。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

虽然在测序和基因分型技术的进步大大提高了我们的能力,以找出与疾病相关的基因变异,我们了解这些变异影响的作用机制能力滞后。该问题的一个重要原因是,许多疾病相关变体位于在正对编码的基因组的区域,这有可能影响控制基因表达更难对预测的机制。在这里,我们提出了一种基于EMSA和DAPA技术,有价值的分子工具,用于识别基因型依赖TF绑定可能导致许多非编码变异体的功能活动…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank Erin Zoller, Jessica Bene, and Lindsey Hays for input and direction in protocol development. MTW was supported in part by NIH R21 HG008186 and a Trustee Award grant from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. ZHP was supported in part by T32 GM063483-13.

Materials

| Custom DNA Oligonucleotides | Integrated DNA Technologies | http://www.idtdna.com/site/order/oligoentry | |

| Potassium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP366-500 | KCl, for CE buffer |

| HEPES (1M) | Fisher Scientific | 15630-080 | For CE and NE buffer |

| EDTA (0.5M), pH 8.0 | Life Technologies | R1021 | For CE, NE, and annealing buffer |

| Sodium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | BP358-1 | NaCl, for NE buffer |

| Tris-HCl (1M), pH 8.0 | Invitrogen | BP1756-100 | For annealing buffer |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (1X) | Fisher Scientific | MT21040CM | PBS, for cell wash |

| DL-Dithiothreitol solution (1M) | Sigma | 646563 | Reducing agent |

| PMSF | Thermo Scientific | 36978 | Protease Inhibitor |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Thermo Scientific | 78420 | Prevents dephosphorylation of TFs |

| Nonidet P-40 Substitute | IBI Scientific | IB01140 | NP-40, for nuclear extraction |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | For measuring protein concentration |

| Odyssey EMSA Buffer Kit | Licor | 829-07910 | Contains all necessary EMSA buffers |

| TBE Gels, 6%, 12 Wells | Invitrogen | EC6265BOX | For EMSA |

| TBE Buffer (10X) | Thermo Scientific | B52 | For EMSA |

| FactorFinder Starting Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-092-318 | Contains all necessary DAPA buffers |

| Licor Odyssey CLx | Licor | Recommended scanner for DAPA/EMSA | |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic | Gibco | 15240-062 | Contains 10,000 units/mL of penicillin, 10,000 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 25 µg/mL of Fungizone® Antimycotic |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Gibco | 26140-079 | FBS, for culture media |

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Gibco | 22400-071 | Contains L-glutamine and 25mM HEPES |

References

- Hindorff, L. A., et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (23), 9362-9367 (2009).

- Maurano, M. T., et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 337 (6099), 1190-1195 (2012).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 30 (11), 1095-1106 (2012).

- Paul, D. S., Soranzo, N., Beck, S. Functional interpretation of non-coding sequence variation: concepts and challenges. Bioessays. 36 (2), 191-199 (2014).

- Zhang, F., Lupski, J. R. Non-coding genetic variants in human disease. Hum Mol Genet. , (2015).

- Lee, T. I., Young, R. A. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 152 (6), 1237-1251 (2013).

- Slatkin, M. Linkage disequilibrium–understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat Rev Genet. 9 (6), 477-485 (2008).

- Bush, W. S., Moore, J. H. Chapter 11: Genome-wide association studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 8 (12), e1002822 (2012).

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 491 (7422), 56-65 (2012).

- Chang, C. C., et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 4, 7 (2015).

- Purcell, S., et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 81 (3), 559-575 (2007).

- ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 489 (7414), 57-74 (2012).

- Crawford, G. E., et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS). Genome Res. 16 (1), 123-131 (2006).

- Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y., Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 10 (12), 1213-1218 (2013).

- Giresi, P. G., Kim, J., McDaniell, R. M., Iyer, V. R., Lieb, J. D. FAIRE Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 17 (6), 877-885 (2007).

- Kent, W. J., et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12 (6), 996-1006 (2002).

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 518 (7539), 317-330 (2015).

- Martens, J. H., Stunnenberg, H. G. BLUEPRINT: mapping human blood cell epigenomes. Haematologica. 98 (10), 1487-1489 (2013).

- Liu, T., et al. Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biol. 12 (8), R83 (2011).

- Griffon, A., et al. Integrative analysis of public ChIP-seq experiments reveals a complex multi-cell regulatory landscape. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (4), e27 (2015).

- Staudt, L. M., et al. A lymphoid-specific protein binding to the octamer motif of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 323 (6089), 640-643 (1986).

- Singh, H., Sen, R., Baltimore, D., Sharp, P. A. A nuclear factor that binds to a conserved sequence motif in transcriptional control elements of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 319 (6049), 154-158 (1986).

- Weirauch, M. T., et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell. 158 (6), 1431-1443 (2014).

- Ward, L. D., Kellis, M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (Database issue), D930-D934 (2012).

- Boyle, A. P., et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1790-1797 (2012).

- Hume, M. A., Barrera, L. A., Gisselbrecht, S. S., Bulyk, M. L. UniPROBE, update 2015: new tools and content for the online database of protein-binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (Database issue), D117-D122 (2015).

- Mathelier, A., et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), 142-147 (2014).

- Smith, M. F., Delbary-Gossart, S. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA). Methods Mol Med. 50, 249-257 (2001).

- Franza, B. R., Josephs, S. F., Gilman, M. Z., Ryan, W., Clarkson, B. Characterization of cellular proteins recognizing the HIV enhancer using a microscale DNA-affinity precipitation assay. Nature. 330 (6146), 391-395 (1987).

- . BCA Protein Assay Kit: User Guide Available from: https://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/MAN0011430_Pierce_BCA_Protein_Asy_UG.pdf (2014)

- Wijeratne, A. B., et al. Phosphopeptide separation using radially aligned titania nanotubes on titanium wire. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 7 (21), 11155-11164 (2015).

- Silva, J. M., McMahon, M. The Fastest Western in Town: A Contemporary Twist on the Classic Western Blot Analysis. J. Vis. Exp. (84), (2014).

- Lu, X., et al. Lupus Risk Variant Increases pSTAT1 Binding and Decreases ETS1 Expression. Am J Hum Genet. 96 (5), 731-739 (2015).

- Ramana, C. V., Chatterjee-Kishore, M., Nguyen, H., Stark, G. R. Complex roles of Stat1 in regulating gene expression. Oncogene. 19 (21), 2619-2627 (2000).

- Fillebeen, C., Wilkinson, N., Pantopoulos, K. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for the Study of RNA-Protein Interactions: The IRE/IRP Example. J. Vis. Exp. (94), e52230 (2014).

- Heng, T. S., Painter, M. W. Immunological Genome Project, C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 9 (10), 1091-1094 (2008).

- Wu, C., et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 10 (11), R130 (2009).

- Wu, C., Macleod, I., Su, A. I. BioGPS and MyGene.info: organizing online, gene-centric information. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (Database issue), D561-D565 (2013).

- Wang, J., et al. Sequence features and chromatin structure around the genomic regions bound by 119 human transcription factors. Genome Res. 22 (9), 1798-1812 (2012).

- Holden, N. S., Tacon, C. E. Principles and problems of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 63 (1), 7-14 (2011).

- Xu, J., Liu, H., Park, J. S., Lan, Y., Jiang, R. Osr1 acts downstream of and interacts synergistically with Six2 to maintain nephron progenitor cells during kidney organogenesis. Development. 141 (7), 1442-1452 (2014).

- Yang, T. -. P., et al. Genevar: a database and Java application for the analysis and visualization of SNP-gene associations in eQTL studies. Bioinformatics. 26 (19), 2474-2476 (2010).

- Fort, A., et al. A liver enhancer in the fibrinogen gene cluster. Blood. 117 (1), 276-282 (2011).

- Solberg, N., Krauss, S. Luciferase assay to study the activity of a cloned promoter DNA fragment. Methods Mol Biol. 977, 65-78 (2013).

- Rahman, M., et al. A repressor element in the 5′-untranslated region of human Pax5 exon 1A. Gene. 263 (1-2), 59-66 (2001).

- Mali, P., et al. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science. 339 (6121), 823-826 (2013).