体外孤独な蜂の飼育: 幼虫の危険因子を評価するためのツール

Summary

開花植物の殺菌剤散布が孤独な蜂花粉媒介殺菌剤残留物の高濃度にあります。生体外で実験室の実験を使用して-飼育ハチの幼虫、この研究調査ホストと非ホストの植物由来殺菌剤処理した花粉を消費のインタラクティブな効果。

Abstract

孤独な蜂は、野生とマネージ作物の重要な受粉サービスを提供する、この種豊富なグループは、主として農薬規制研究に見過ごされています。殺菌剤残留物への暴露のリスクがスプレー蜂が巣を提供する花粉を収集しているときや、ホスト植物の近くが発生した場合に特に高する可能性があります。植物 (oligolecty) の選択グループから花粉を消費するツツハナバチの種、非ホストの植物からの花粉を使用することができないことは殺菌剤関連毒性の危険因子を増やすことができます。本稿では、正常に oligolectic オーチャードメイソン蜂、標準化された実験室条件下での細胞培養皿の中で前のステージに卵からのツツハナバチ ribifloris sensu lato をリアに使用されるプロトコルについて説明します。体外の飼育ミツバチ蜂フィットネスに及ぼす殺菌剤の露出と花粉のソースを調べるに使用されます。実験 2 × 2 完全に交差因子設計に基づき、前バイオマス、幼虫の発生時間生存し、定量化、幼虫のフィットネスに殺菌剤の露出と花粉の源のメインと対話型効果を調べます。この手法の主な利点は、体外を使用して-飼育ミツバチ自然背景変動を削減し、複数の実験的パラメーターの同時操作。記述されていたプロトコルは、ミツバチの健康に影響を与える要因のスイートを含むテストの仮説のための多目的なツールを示します。保全努力の重要な不変の成功で満たされる、生理学的および環境の蜂の減少要因の複雑な相互作用にこのような洞察力が重要なことを証明します。

Introduction

訪花昆虫群集の1の支配的なグループとしての役割を与え、ミツバチの人口世界的な損失は、食料安全保障と生態系の安定性2,3,4,5,6 に脅威を与える ,7。両方の管理と野生のミツバチの人口の減少傾向は、生息地の断片化、新興寄生虫および病原体、遺伝的多様性の損失、外来種3 の導入を含むいくつかの共有リスク要因に起因しています。 ,4,7,8,9,10、11,12。特に、殺虫剤、(例えば、ネオニコチノイド) の使用の劇的な増加は、蜂13,14,15間の有害な影響に直接リンクされています。いくつかの研究は、ネオニコチノイドとエルゴステ ロール生合成阻害 (EBI) 殺菌剤との相乗効果が複数の蜂種16,17,18の間で高い死亡率につながることを示しています。,19,20,21,22. それにもかかわらず、防かび剤、長い ‘ 蜂-、安全であると考え続ける多くの精査23なしブルームの作物に噴霧します。採餌蜂は、定期的に殺菌剤の残留24,25,26で汚染された花粉荷を戻すために記載されています。このような殺菌剤 ladenpollen の消費が幼虫蜂27,28,29,30と大人の蜂16間で致死性効果のスイートの中で高い死亡率を引き起こす可能性,31,32,33,34. 最近の研究提案する殺菌剤が蜂と花粉媒介微生物35間重要な共生をそれにより中断ハイブに格納されている花粉内の微生物群集を変えることによってミツバチの損失を引き起こす可能性があります。

孤独な蜂はいくつか野生および農業植物36,37,の受粉のために不可欠ですが38、花粉媒介者のこの多様なグループは農薬モニタリング調査であまり注目を受けています。大人の孤独な女性の巣 5 10 密閉育児室、母性収集した花粉や蜜、単一卵39の有限質量とそれぞれ貯蔵します。孵化後、幼虫は割り当てられた花粉提供と十分な栄養40,41を取得する関連付けられている花粉媒介微生物叢に依存します。社会のライフ スタイルの利点がない、ために、孤独な蜂は農薬暴露42より傷つきやすいかもしれません。社会蜂スプレー、次に赤字中が補償する例えば、いくつかの労働者によって拡張し、新興国ひな、単一の大人の孤独な女性の死終了すべての繁殖活動43。感受性のような差異は、マネージ コードと野生の蜂同様の十分な保護を確保するための生態毒物学的研究の多様な蜂イチイを組み込む必要のあるを強調表示します。ただし、研究の一握り、脇から殺菌剤曝露の影響の調査主に当てている社会蜂18,23,32,44,45 ,46,47,48,49。

孤独な蜂属ツツハナバチ(図 1) はいくつかの重要な果物とナット作物39,50,51,53,の効率的な花粉媒介者として世界的に使用されています。53他のマネージの送粉者と24,54,55,56,,5758のグループ、、成人のツツハナバチ蜂が日常的に。ブルームの作物44に噴霧殺菌剤にさらされます。最近散布作物の成人女性が収集し、殺菌剤を含んだ花粉の後で開発の幼虫の唯一の食事療法を形作る彼らのひな部屋を買いだめ。汚染された花粉規定を消費してその後殺菌剤の残留42幼虫を公開できます。暴露のリスクはいくつか密接に関連ホスト植物59,60,61上だけ飼料 oligolectic 種以上あります。特定の野生のミツバチは、たとえば、優先的に寄生62の減少の手段として低品質キク科花粉用飼料に表示されます。しかし、殺菌剤影響 oligolectic 孤独な蜂の幼虫のフィットネスを与える程度は経験的定量化されていません。本研究の目的は、メインをテストするためのプロトコルを開発する、対話型生体外でのフィットネスに及ぼす殺菌剤の露出と花粉のソースは孤独な蜂を飼育しました。調べるために、 O. ribifloris sensu lato (s. l.) の卵を商業的に得ることができる (材料表)。この人口はネイティブの粉と地域53,報63,64 内花蜜豊富なヒイラギナンテン aquifolium (オレゴンブドウ) のの強い好みとしてその重要性のため理想的です(図 2)。

図 1。大人のツツハナバチ ribiflorisの高解像度写真。写真クレジット研究昆虫博士ジム杖 USDA-ARSこの図の拡大版を表示するのにはここをクリックしてください。

図 2。.フォア グラウンドでネスト女性ツツハナバチ ribifloris (s. l.)の葦をネスト Phragmite商工会議所パーティションと葦の端子のプラグは、練りの葉から構成されます。写真クレジット キンボール クラーク氏 NativeBees.comこの図の拡大版を表示するのにはここをクリックしてください。

本研究の第一の目的は消費する (開発時間と前バイオマスの面で測定される) 幼虫のフィットネスで花粉を殺菌剤処理の効果を評価します。広く用いられている殺菌剤 propiconazole への露出は、いくつか種23,24,32,44,45、間大人のミツバチの間で死亡率の増加にリンクされている中 54,55,56,57,58,65,66,67, 幼虫蜂への影響が小さい知られています。本研究の第二の目的は、幼虫フィットネスで非ホスト花粉を消費の影響を評価することです。以前の研究では、oligolectic 蜂の幼虫が非ホスト花粉68消費を強制する場合の開発に失敗することを示します。このような結果は、蜂生理学69、花粉生化学70、および関連付けられている天然の花粉規定71有益マイクロバイ変化に起因する可能性があります。本研究の第 3 の目的は、幼虫のフィットネスに殺菌剤治療と食事花粉のインタラクティブな効果を評価することです。

母体サイズなど多数の生物学的特徴、準備率、採餌戦略と花粉量72,73,74,75知られている孤独な蜂の幼虫のフィットネスに影響を与えます。これらの要因は、葦、幼虫の健康を評価するとき防御実験デザインの開発に挑戦をもたらすとの間の有意な変動を導入できます。また、密封された入れ子葦中幼生が発生すると、子孫にそのような変動の影響が視覚化することは困難と定量化された非殺傷技術 (図 3) を使用してせず。このような課題を克服するために本研究の内ですべての仮説は、その入れ子の葦の外飼育幼虫を用いたテストされます。実験的なデザインを完全に交差 2 × 2 因子のセットアップ、2 レベルから成る各因子とを表します因子 1: 殺菌剤暴露 (殺菌剤;ない殺菌剤);要因 2: 花粉の源 (ホスト花粉、非ホスト花粉)。蜂は、卵から管理された実験室の条件下で無菌 multiwell 細胞培養皿の中で前の段階に発生します。それぞれはよく花粉規定と 1 つの卵の標準化された量の貯蔵は個別に。孵化後、幼虫が井戸の内で割り当てられている花粉のフィードし、幼虫の発育が完了すると蛹化を開始します。過去の研究では、原因不明の死亡が野生49,76で遭遇よりもこの人工飼育環境内で発生したミツバチの間で低いことを示しています。生体外での使用-飼育ミツバチ フィールド ベースの研究上のいくつかの利点がある: 1) 自然変動とフィールド ベースの研究に通常関連付けられているコントロール不良要因の交絡影響を最小限に抑える2) ことができます;、試験治療グループ間で同時にテストに関心の各因子の操作の複数のレベル3) 複製の数があらかじめ決められた、することができ、各複製の実験的要因を個別に操作できます。4) 幼虫応答変数が簡単に可視化し、不穏な隣接する幼虫; せず個別に記録されました。5) プロトコルは、複数の要因と応答の変数を含むより複雑な実験的デザインに合わせて変更できます。

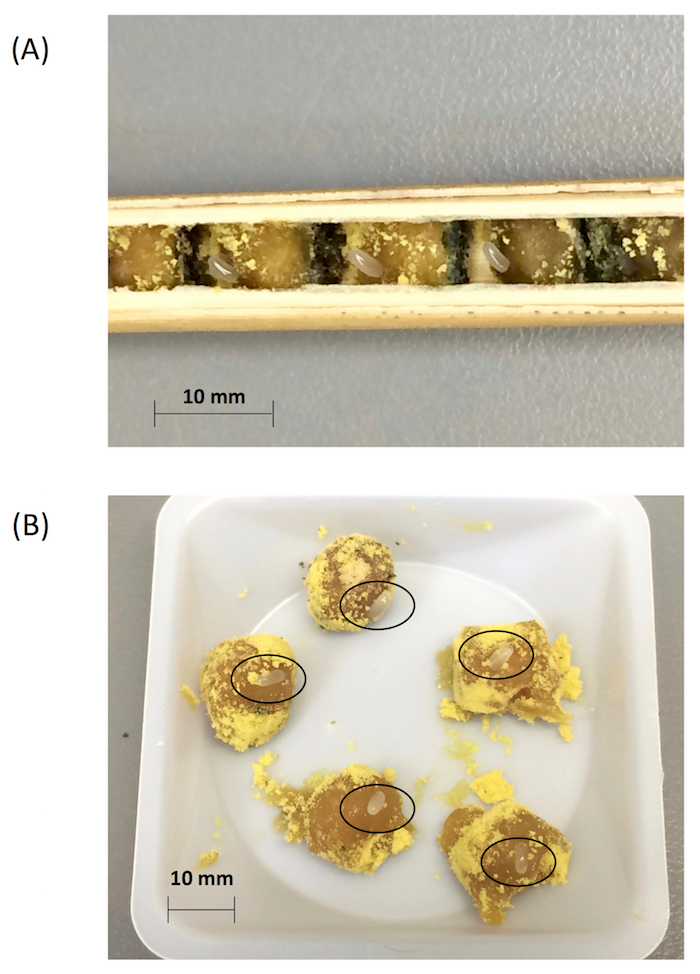

図 3。自然営巣リード内の内容ツツハナバチ ribifloris (s. l.). (A)たて個々 の室、花粉規定とパーティション、および(B)を示す解剖葦収穫花粉規定と関連付けられた卵 (黒い丸で示されます) のクローズ アップ。この図の拡大版を表示するのにはここをクリックしてください。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

その自然営巣葦、研究室の条件の下で外の蜂を飼育幼虫フィットネスに係る複数の仮説のテストが可能します。正体不明の要因は蜂の死亡率を引き起こすリスク評価に関する研究継続する生体外で実験助けることができる潜在的な脅威を特定し、野生花粉12 のこの種豊富なグループの経営慣行を通知 ,38,49,<s…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

著者に感謝キンボール クラークとティム クローツツハナバチネスト葦を提供するため、メレディス ・ ネスビットとモリー Bidwell ラボ、夫妻のカメロン Currie、クリステル Guédot テリー ・ グリスウォルド、マイケル ・ Branstetter の 3 つの匿名のレビューについて原稿を改善した、有用なコメント。この作品は、米国農務省農業研究サービス充当資金 (現在研究情報システム #3655-21220-001)、ウィスコンシン州農務省、貿易、および消費者保護 (#197199)、(の下で全米科学財団によって支えられました。グラント号DEB-1442148)、DOE グレイト レイクス バイオ エネルギー研究センター (科学 BER ・ デ ・ FC02-07ER64494 の DOE のオフィス)。

Materials

| eggs of O. ribifloris sensu lato (s.l.) | Kaysville, Davis County, Utah, USA | ||

| Osmia reeds | Nativebees.com | NA | Freshly plugged reeds |

| Dissection set | VWR | 89259-964 | Sterilize before use |

| Long Nose Pliers | Husky | 1006 | |

| 6 well culture plates | VWR | 10062-892 | Sterile sealed |

| 48 well culture plates | VWR | 10062-898 | Sterile sealed |

| Petri dishes | VWR | 25373100 | Sterile sealed |

| Square Weighing Boats | VWR | 10770-448 | |

| Camel Hair Brush | Bioquip | 1153A | |

| Tin capsules | EA Consumables | D1021 | Sterilize before use |

| Sucrose | VWR | 470302-808 | |

| Propiconazole 14.3 | Quali-Ppro | 60207-90-1 | Propiconazole 14.3% |

| Honey bee pollen | Bee energised | 897098001244 | Untreated, natural, raw pollen |

| Microbalance | VWR | 10204-990 | |

| Pulverisette | LAB SYNERGY INC. | 30334913 | |

| Wooden sticks | VWR | 470146908 | Sterilize before use |

| Sealing tape | VWR | 89097-912 | |

| Microscope | VWR | 89403-384 | |

| Planting tray | VWR | 470150-632 | |

| Ethanol | VWR | BDH1158-4LP | |

| Centrifuge tube | VWR | 21008936 | |

| Microsyringe | Cole-Palmer | UX-07940-07 | |

| Rubber tweezer | Amazon | B0135HWPN4 | |

| Syringe needles | VWR | 89219-334 | |

| Freeze drier | Labcono | LFZ-1L | |

| Statistical software | SPSS | Version 21.0 |

References

- Klein, A. -. M., et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. P Roy Soc Lond B Bio. 274 (1608), 303-313 (2007).

- Biesmeijer, J. C. J., et al. Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science. 313 (5785), 351-354 (2006).

- Potts, S. G., Biesmeijer, J. C., Kremen, C., Neumann, P., Schweiger, O., Kunin, W. E. Global pollinator declines: Trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol. 25 (6), 345-353 (2010).

- Cameron, S. A., et al. Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 108 (2), 662-667 (2011).

- Gallai, N., Salles, J. M., Settele, J., Vaissière, B. E. Economic valuation of the vunerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecol Econ. 68 (3), 810-821 (2009).

- Fontaine, C., Dajoz, I., Meriguet, J., Loreau, M. Functional diversity of plant-pollinator interaction webs enhances the persistence of plant communities. Plos Biol. 4 (1), 0129-0135 (2006).

- Kluser, S., Peduzzi, P. . Global pollinator decline: a literature review. , (2007).

- Brown, M. J. F., Paxton, R. J. The conservation of bees: a global perspective. Apidologie. 40 (3), (2009).

- Lebuhn, G., et al. Detecting insect pollinator declines on regional and global scales. Conserv Biol. 27 (1), (2013).

- Vanengelsdorp, D., Meixner, M. D. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. J Invertebr Pathol. , S80-S95 (2010).

- Pettis, J. S., Delaplane, K. S. Coordinated responses to honey bee decline in the USA. Apidologie. 41 (3), 256-263 (2010).

- Sandrock, C., Tanadini, L. G., Pettis, J. S., Biesmeijer, J. C., Potts, S. G., Neumann, P. Sublethal neonicotinoid insecticide exposure reduces solitary bee reproductive success. Agr Forest Entomol. 16 (2), (2014).

- Van der Sluijs, J. P., Simon-Delso, N., Goulson, D., Maxim, L., Bonmatin, J. M., Belzunces, L. P. Neonicotinoids, bee disorders and the sustainability of pollinator services. Curr Opin Env Sust. 5 (3), (2013).

- Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C., Rotheray, E. L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science. 347 (6229), (2015).

- Johnson, R. M., Ellis, M. D., Mullin, C. A., Frazier, M. Pesticides and honey bee toxicity – USA. Apidologie. 41 (3), (2010).

- Iwasa, T., Motoyama, N., Ambrose, J. T., Roe, R. M. Mechanism for the differential toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Crop Protection. 23 (5), 371-378 (2004).

- Glavan, G., Bozic, J. The synergy of xenobiotics in honey bee Apis mellifera: mechanisms and effects. Acta Biol. Slov. 56, 11-27 (2013).

- Biddinger, D. J., et al. Comparative toxicities and synergism of apple orchard pesticides to Apis mellifera (L.) and Osmia cornifrons (Radoszkowski). PLoS ONE. 8 (9), e72587 (2013).

- Thompson, H. M., Fryday, S. L., Harkin, S., Milner, S. Potential impacts of synergism in honeybees (Apis mellifera) of exposure to neonicotinoids and sprayed fungicides in crops. Apidologie. 45 (5), 545-553 (2014).

- Jansen, J. -. P., Lauvaux, S., Gruntowy, J., Denayer, J. Possible synergistic effects of fungicide-insecticide mixtures on beneficial arthropods. IOBC-WPRS Bulletin. 125, 28-35 (2017).

- Robinson, A., Hesketh, H., et al. Comparing bee species responses to chemical mixtures: Common response patterns?. PLoS ONE. 12 (6), (2017).

- Sgolastra, F., Medrzycki, P., et al. Synergistic mortality between a neonicotinoid insecticide and an ergosterol-biosynthesis-inhibiting fungicide in three bee species. Pest Management Science. 73 (6), 1236-1243 (2017).

- Ladurner, E., Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P., Maini, S. Assessing delayed and acute toxicity of five formulated fungicides to Osmia lignaria and Apis mellifera. Apidologie. 36 (3), 449-460 (2005).

- Mullin, C. A., et al. High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in North American apiaries: implications for honey bee health. PloS one. 5 (3), e9754 (2010).

- Pettis, J. S., Lichtenberg, E. M., Andree, M., Stitzinger, J., Rose, R., Vanengelsdorp, D. Crop pollination exposes honey bees to pesticides which alters their susceptibility to the gut pathogen Nosema ceranae. PloS one. 8 (7), e70182 (2013).

- David, A., et al. Widespread contamination of wildflower and bee-collected pollen with complex mixtures of neonicotinoids and fungicides commonly applied to crops. Environ Int. 88, 169-178 (2016).

- Zhu, W., Schmehl, D. R., Mullin, C. A., Frazier, J. L. Four common pesticides, their mixtures and a formulation solvent in the hive environment have high oral toxicity to honey bee larvae. PloS one. 9 (1), e77547 (2014).

- Simon-Delso, N., Martin, G. S., Bruneau, E., Minsart, L. A., Mouret, C., Hautier, L. Honeybee colony disorder in crop areas: The role of pesticides and viruses. PLoS ONE. 9 (7), (2014).

- Park, M. G., Blitzer, E. J., Gibbs, J., Losey, J. E., Danforth, B. N. Negative effects of pesticides on wild bee communities can be buffered by landscape context. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 282 (1809), 20150299-20150299 (2015).

- Bernauer, O. M., Gaines-Day, H. R., Steffan, S. A. Colonies of bumble bees (Bombus impatiens) produce fewer workers, less bee biomass, and have smaller mother queens following fungicide exposure. Insects. 6 (2), 478-488 (2015).

- Williamson, S. M., Wright, G. A. Exposure to multiple cholinergic pesticides impairs olfactory learning and memory in honeybees. J Exp Biol. 216 (10), 1799-1807 (2013).

- Artz, D. R., Pitts-Singer, T. L. Effects of fungicide and adjuvant sprays on nesting behavior in two managed solitary bees, Osmia lignaria and Megachile rotundata. PLoS ONE. 10 (8), e0135688 (2015).

- Pilling, E. D., Bromleychallenor, K. A. C., Walker, C. H., Jepson, P. C. Mechanism of synergism between the pyrethroid insecticide lambda-cyhalothrin and the imidazole fungicide prochloraz, in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L). Pestic Biochem Phys. 51 (1), 1-11 (1995).

- Johnson, R. M., Wen, Z., Schuler, M. A., Berenbaum, M. R. Mediation of pyrethroid insecticide toxicity to honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. J. Econ. Entomol. 99 (4), 1046-1050 (2006).

- Steffan, S. A., Dharampal, P. S., Diaz-Garcia, L. A., Currie, C. R., Zalapa, J. E., Hittinger, C. T. Empirical, metagenomic, and computational techniques illuminate the mechanisms by which fungicides compromise bee health. JoVE. (128), e54631 (2017).

- Batra, S. W. T. Solitary bees. Sci Am. 250 (2), 120-127 (1984).

- Linsley, E. G. The ecology of solitary bees. Hilgardia. 27 (19), 543-599 (1958).

- Garibaldi, L. A., et al. Wild Pollinators Enhance Fruit Set of Crops Regardless of Honey Bee Abundance. Science. 339 (6127), 1608-1611 (2013).

- Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. . How to manage the blue orchard bee. , (2001).

- Keller, A., Grimmer, G., Steffan-Dewenter, I. Diverse microbiota identified in whole intact nest chambers of the red mason bee Osmia bicornis (Linnaeus 1758). PLoS ONE. 8 (10), e78296 (2013).

- Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. Development and Emergence of the Orchard Pollinator Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Environmental Entomology. 29 (1), 8-13 (2000).

- Brittain, C., Potts, S. G. The potential impacts of insecticides on the life-history traits of bees and the consequences for pollination. Basic and Applied Ecology. 12 (4), 321-331 (2011).

- Arena, M., Sgolastra, F. A meta-analysis comparing the sensitivity of bees to pesticides. Ecotoxicology. 23 (3), 324-334 (2014).

- Ladurner, E., Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P., Maini, S. Foraging and nesting behavior of Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in the presence of fungicides: cage studies. J Econ Entomol. 101 (3), 647-653 (2008).

- Huntzinger, A. C. I., James, R. R., Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. Fungicide tests on adult alfalfa leafcutting bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Econ Entomol. 101 (4), 1088-1094 (2008).

- Tsvetkov, N., et al. Chronic exposure to neonicotinoids reduces honey bee health near corn crops. Science. 356 (6345), 1395-1397 (2017).

- Mao, W., Schuler, M. A., Berenbaum, M. R. Disruption of quercetin metabolism by fungicide affects energy production in honey bees (Apis mellifera). P Natl Acad Sci. 114 (10), 2538-2543 (2017).

- Blacquière, T., Smagghe, G., Van Gestel, C. A. M., Mommaerts, V. Neonicotinoids in bees: A review on concentrations, side-effects and risk assessment. Ecotoxicology. 21 (4), 973-992 (2012).

- Sgolastra, F., Tosi, S., Medrzycki, P., Porrini, C., Burgio, G. Toxicity of spirotetramat on solitary bee larvae, Osmia cornuta (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), in laboratory conditions. Journal of Apicultural Science. 59 (2), 73-83 (2015).

- Mader, E., Spivak, M., Evans, E. . Managing Alternative Pollinators. , (2010).

- Bosch, J., Kemp, W. P. Developing and establishing bee species as crop pollinators: the example of Osmia spp.(Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) and fruit trees. B Entomol Res. 92 (1), 3-16 (2002).

- Sampson, B. J., Rinehart, T. A., Kirker, G. T., Stringer, S. J., Werle, C. T. Phenotypic variation in fitness traits of a managed solitary bee, Osmia ribifloris (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Econ Entomol. 108 (6), 2589-2598 (2015).

- Sampson, B. J., Cane, J. H., Kirker, G. T., Stringer, S. J., Spiers, J. M. Biology and management potential for three orchard bee species (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae): Osmia ribifloris Cockerell, O. lignaria (Say) and O.chalybea Smith with emphasis on the former. Acta Hort. 810, 549-555 (2009).

- Hladik, M. L., Vandever, M., Smalling, K. L. Exposure of native bees foraging in an agricultural landscape to current-use pesticides. Sci Total Environ. 542, 469-477 (2016).

- Long, E. Y., Krupke, C. H. Non-cultivated plants present a season-long route of pesticide exposure for honey bees. Nat Commun. 7, (2016).

- Krupke, C. H., Hunt, G. J., Eitzer, B. D., Andino, G., Given, K. Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS ONE. 7 (1), e29268 (2012).

- Stoner, K. A., Eitzer, B. D. Using a hazard quotient to evaluate pesticide residues detected in pollen trapped from honey bees (Apis mellifera) in Connecticut. PLoS ONE. 8 (10), e77550 (2013).

- Sánchez-Bayo, F., Goulson, D., Pennacchio, F., Nazzi, F., Goka, K., Desneux, N. Are bee diseases linked to pesticides? – A brief review. Environ Int. 89, 7-11 (2016).

- Steffan-Dewenter, I., Klein, A. -. M., Gaebele, V., Alfert, T., Tscharntke, T. Bee diversity and plant-pollinator interactions in fragmented landscapes. Specialization and generalization in plant-pollinator interactions. , 387-410 (2006).

- Kremen, C., Ricketts, T. Global perspectives on pollination disruptions. Conserv Biol. 14 (5), 1226-1228 (2000).

- Memmott, J., Waser, N. M., Price, M. V. Tolerance of pollination networks to species extinctions. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 271 (1557), 2605-2611 (2004).

- Spear, D. M., Silverman, S., Forrest, J. R. K. Asteraceae pollen provisions protect Osmia mason bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) from brood parasitism. The American Naturalist. 187 (6), 797-803 (2016).

- Rust, R. W. Biology of Osmia (Osmia) ribifloris Cockerell (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Kansas Entomol Soc. 59, 89-94 (1986).

- Torchio, P. F. Osmia ribifloris, a native bee species developed as a commercially managed pollinator of highbush blueberry (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Kansas Entomol Soc. 63 (633), 427-436 (1990).

- Sanchez-Bayo, F., Goka, K. Pesticide residues and bees – A risk assessment. PLoS ONE. 9 (4), e94482 (2014).

- Kasiotis, K. M., Anagnostopoulos, C., Anastasiadou, P., Machera, K. Pesticide residues in honeybees, honey and bee pollen by LC-MS/MS screening: Reported death incidents in honeybees. Sci Total Environ. 485 (1), 633-642 (2014).

- Stanley, J., Sah, K., Jain, S. K., Bhatt, J. C., Sushil, S. N. Evaluation of pesticide toxicity at their field recommended doses to honeybees, Apis cerana and A. mellifera through laboratory, semi-field and field studies. Chemosphere. 119, 668-674 (2015).

- Praz, C. J., Müller, A., Dorn, S. Specialized bees fail to develop on non-host pollen: Do plants chemically protect their pollen?. Ecology. 89 (3), 795-804 (2008).

- Sedivy, C., Müller, A., Dorn, S. Closely related pollen generalist bees differ in their ability to develop on the same pollen diet: Evidence for physiological adaptations to digest pollen. Funct Ecol. 25 (3), 718-725 (2011).

- Williams, N. M. Use of novel pollen species by specialist and generalist solitary bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Oecologia. 134, (2003).

- Graystock, P., Rehan, S. M., McFrederick, Q. S. Hunting for healthy microbiomes: determining the core microbiomes of Ceratina, Megalopta, and Apis bees and how they associate with microbes in bee collected pollen. Conserv Genet. 18 (3), 1-11 (2017).

- Bosch, J., Vicens, N. Relationship between body size, provisioning rate, longevity and reproductive success in females of the solitary bee Osmia cornuta. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 60 (1), 26-33 (2006).

- Bosch, J., Vicens, N. Body size as an estimator of production costs in a solitary bee. Ecol Entomol. 27 (2), 129-137 (2002).

- Radmacher, S., Strohm, E. Factors affecting offspring body size in the solitary bee Osmia bicornis (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae). Apidologie. 41 (2), 169-177 (2010).

- Seidelmann, K. Open-cell parasitism shapes maternal investment patterns in the Red Mason bee Osmia rufa. Behav Ecol. 17 (5), (2006).

- Becker, M. C., Keller, A. Laboratory rearing of solitary bees and wasps. Insect Science. 23 (6), 918-923 (2016).

- Bosch, J. The nesting behaviour of the mason bee Osmia cornuta (Latr) with special reference to its pollinating potential (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae). Apidologie. 25, 84-93 (1994).

- Krunić, M., Stanisavljević, L., Pinzauti, M., Felicioli, A. The accompanying fauna of Osmia cornuta and Osmia rufa and effective measures of protection. B Insectol. 58 (2), 141-152 (2005).

- Elliott, S. E., Irwin, R. E., Adler, L. S., Williams, N. M. The nectar alkaloid, gelsemine, does not affect offspring performance of a native solitary bee, Osmia lignaria (Megachilidae). Ecol Entomol. 33 (2), 298-304 (2008).

- Hendriksma, H. P., Härtel, S., Steffan-Dewenter, I. Honey bee risk assessment: New approaches for in vitro larvae rearing and data analyses. Methods Ecol and Evol. 2 (5), 509-517 (2011).

- Aupinel, P., et al. Improvement of artificial feeding in a standard in vitro method for rearing Apis mellifera larvae. B Insectol. 58 (2), 107-111 (2005).

- Beekman, M., Ratnieks, F. L. W. Long-range foraging by the honey-bee, Apis mellifera L. Funct Ecol. 14 (4), 490-496 (2000).

- Gathmann, A., Tscharntke, T. Foraging ranges of solitary bees. J Anim Ecol. 71 (5), 757-764 (2002).

- Greenleaf, S. S., Williams, N. M., Winfree, R., Kremen, C. Bee foraging ranges and their relationship to body size. Oecologia. 153 (3), 589-596 (2007).

- . Bee Pollen Supplement – Bee Rescued Available from: https://beerescued.com/product/bee-rescued-bee-pollen-supplement/ (2018)

- Cane, J. H., Griswold, T., Parker, F. D. Substrates and Materials Used for Nesting by North American Osmia Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes: Megachilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 100 (3), 350-358 (2007).