你是聪明还是勤劳?赞美是如何影响儿童的动机

English

Share

Overview

资料来源: 实验室的朱迪思 · Danovitch 和尼古拉 Noles — — 路易斯维尔大学

想象一下如何滑冰教学的两个孩子。这是一个艰巨的任务,为他们两个,和他们经常掉下来。后第一次落下,一个孩子说,滑冰是太难了,想要回家。另一个孩子看起来很享受所面临的挑战和热切地回来了每次跌倒后。孩子们为什么有这种不同的态度,关于相同的任务?原因之一可能是能力的他们有不同的观念或信仰的性质。

根据心理学家卡罗尔 · 德维克,有些人有固定的心态,和有些人有一种成长的心态。有固定的心态的人相信,智力或能力固定的无法更改。当这些人面对挑战,就像学习怎么滑冰,他们倾向于认为,如果一个新的技能并不能轻易,那么,他们是只不是擅长它。他们作为有能力改变,看不到他们的技能,因此他们决定它是无用的继续努力。具有成长心态的人有相反的态度。他们认为可以通过辛勤工作,开发能力,他们继续努力提高即使他们最初没有成功。

这些不同的思维模式是如何发展的?影响儿童的持久性和动力,成功的一个因素是他们的成功由其他人所描述的方式。具体来说,赞美孩子们收到的成年人,例如家长及教师,那种可以有强大影响其随后的动机来执行一项具有挑战性的任务。

该视频演示如何衡量赞美影响儿童的动机的基础开发的穆勒和德维克的方法。1

Procedure

Results

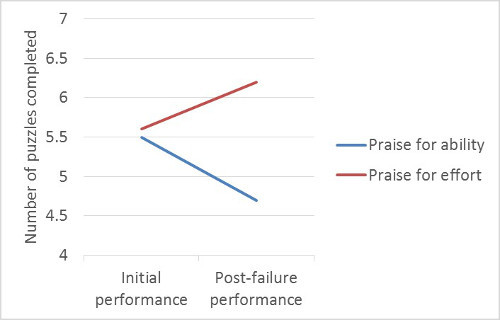

Researchers tested 80 9- to 11-year-old children (n = 40 in each condition) and found that the type of praise children received had a significant effect on their performance. Both groups of children started out with similar performance on the initial puzzles, but the children who were praised for ability showed a significant decrease in their performance after failing at the more difficult puzzles. Children who were praised for effort showed an improvement in performance after the failure experience, suggesting that hearing their initial success was a function of their effort motivated them to work even harder on the puzzles after failing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average initial and post-failure performance for children in each condition.

Applications and Summary

The finding that a brief statement of praise from an experimenter has significant consequences for a child’s motivation to complete a challenging task has major implications for how parents and teachers talk to children. Although saying “You’re so smart” might sound like a good way to praise a child, these findings suggest that doing so fosters the development of a fixed mindset, which can be detrimental to children’s willingness to persist in challenging tasks. In order to foster the development of a growth mindset and motivate children to persist in the face of challenges, parents and teachers should praise children for their effort instead. This is also true in the case of criticism. Criticizing effort (e.g., “You lost the race because you did not practice as much as the winner”) is more likely to motivate children to continue working to achieve a goal than criticizing ability (e.g., “You lost the race because you are not as fast a runner”).

Praise influences mindset, and mindset influences many different variables related to motivation and how people face challenges. Luckily, a mindset is not fixed forever. Even children who typically have a fixed mindset can be shifted into a growth mindset with the right kind of praise and instruction. More importantly, the effects of fostering either a growth or fixed mindset are not limited to children. Carol Dweck has found that these principles also apply to adults in a variety of domains, including the workplace, romantic relationships, and politics.

References

- Mueller, C.M., & Dweck, C.S. Praise for intelligence can undermine children's motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 75 (1), 33-52 (1998).

Transcript

A child’s motivation to succeed at a task—whether a school assignment, sports event, or craft—is heavily influenced by their mindset and how they perceive themselves.

According to psychologist Carol Dweck, children fall into one of two mindset categories: fixed or growth.

Those with a fixed mindset aren’t likely to persist in learning a new skill, like ice-skating, if it doesn’t come naturally to them. They’re not motivated to keep trying, because they believe their abilities can’t change—even with hard work.

In contrast, children with a growth mindset think that their skills can be improved with effort. Thus, even after failing a few times, they are motivated to persist when presented with difficult tasks.

Although a child’s mindset deals with how they think about themselves, it can be shaped by how other people—especially parents and teachers—talk about their traits and abilities.

If a child’s success at a task is praised as being due to inherent ability, this can actually instigate a fixed mindset.

As a result, children may conclude that tasks they find difficult are either beyond their abilities or impossible to complete, resulting in a lack of motivation to persist in performing them.

Using puzzles, this video demonstrates how to explore whether different types of praise affect motivation in children, and describes how to design an experiment, and collect and interpret data, as well as apply the findings to build motivation in both children and adults.

In this experiment, children between the ages of 9 and 11 are asked to complete three sets of ten tangram puzzles.

As these types of puzzles consist of simple shapes, have straightforward instructions, and can be of varying difficulties, they are wonderful tools to assess children’s motivation and persistence at a task.

Children are first given a puzzle set of medium difficulty. The number of puzzles a child successfully completes in five minutes serves as an initial measure of their performance.

Afterwards, children are congratulated on their results, and randomly assigned to one of two praise condition groups: ability or effort.

Children in the first group are told they are smart at puzzles. This type of praise emphasizes children’s puzzle-solving ability, and encourages a fixed mindset.

In contrast, children in the second group are praised for being hard-working, which emphasizes the effort they put into solving puzzles, and fosters a growth mindset.

The type of praise that children receive—and the mindset they develop in response—is expected to influence their performance and motivation to succeed on later puzzles.

Children are then given the second collection of tangram puzzles. The trick here is that these puzzles are much more difficult than the previous ones.

As children are expected to be able to solve fewer puzzles in this round, it is meant to provide them with a “failure” experience. Importantly, this cleverly sets up the third and final collection of tangram puzzles as a challenge to be overcome.

This third set—like the first—is also of medium difficulty. The number of puzzles solved here provides a post-failure measure of performance.

In this instance, the dependent variables are the number of puzzles completed during the initial and post-failure performance measures, respectively, in the first and third tangram sets.

Based on previous work by Dweck, it is expected that a child praised for their effort will complete more puzzles in the third tangram set compared to the first set. In other words, their puzzle-solving performance will be higher after their failure experience.

This is likely due to children perceiving themselves as hard-working in response to this type of praise, which inspires them to want to succeed at solving puzzles.

To begin, select a total of 30 tangram puzzles, 20 of which should be moderately difficult for 9-11 year-olds, and 10 that are very hard for a child this age to complete.

When the child arrives, welcome them and explain that they will be solving three sets of puzzles.

Sit across from the child at a table, and demonstrate how to complete an easy tangram puzzle. Explain that once they start working on a puzzle, it must be successfully solved before they can move onto the next one in a set.

Once the child understands the task, hand them the first set of tangrams and begin a timer. Once 5 min have passed, record the number of puzzles the child solved.

Praise the child according to which group they have been assigned: ability (“You must be smart at these puzzles”) or effort (“You must have worked hard at these puzzles.”)

Afterwards, provide the child with the second puzzle set. Once 5 min have passed, inform them that they did much worse on these problems than the previous ones.

Give each child the third and final tangram set, and again record the number of puzzles they solve after 5 min.

After all three sets have been completed, debrief the child and explain that this study was conducted to evaluate how they reacted to different kinds of praise. Reassure them that they did a great job on all of the puzzles, and explain that the second set was actually meant for much older children.

To visualize the data, graph the mean number of puzzles children solved by praise conditions, pre- and post- the failure experience.

Notice that children who were praised for their effort demonstrated increased post-failure performance, suggesting that this type of encouragement motivated them to persist in their hard work, even when it was challenging.

Now that you know how to design a puzzle-based experiment to study the effects of praise on motivation in children, let’s look at other ways praise—and even criticism—can be used to shape human behavior.

The finding that praising effort, and not individual ability, increased persistence can be easily applied to classroom settings, encouraging children to persevere in fields that are perceived as difficult, like the sciences.

In addition to finding that praising a child’s effort motivated them to succeed, psychologists have found that criticizing effort, rather than ability, also increases motivation, which could influence coaching techniques.

For example, a coach criticizing the amount of time a child practiced, rather than their natural skating ability, may be more effective in motivating that child to succeed in the next competition.

Finally, although we’ve focused here on children, adults are also influenced by mindset, as they are malleable at any age, and over time can switch from being fixed to growth—and vice versa.

As a result, psychologists are exploring how praising effort can be applied in the workplace to foster a growth mindset in employees, and improve job satisfaction and productivity.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video exploring the effects of praise on motivation in children. By now, you should understand how tangram puzzles can be used to investigate this question, and be able to collect and interpret children’s puzzle-solving data. Importantly, we’ve reviewed how different types of praise, targeted at either effort or ability, can affect performance in both children and adults.

Thanks for watching!