당신은 똑똑한가요 아니면 근면한가요? 칭찬이 아이들의 동기부여에 미치는 영향

English

Share

Overview

출처: 주디스 다노비치와 니콜라우스 놀스 연구소 — 루이빌 대학교

스케이트하는 법을 두 아이에게 가르친다고 상상해 보십시오. 그것은 둘 다 어려운 작업이며, 그들은 자주 아래로 떨어집니다. 처음으로 쓰러진 한 아이는 스케이트가 너무 어렵고 집에 가고 싶다고 말합니다. 다른 아이는 도전을 즐기고 매번 쓰러진 후 열심히 다시 돌아오는 것 같습니다. 왜 아이들은 같은 일에 대해 다른 태도를 가지고 있는가? 한 가지 이유는 그들이 능력의 본질에 대해 서로 다른 사고 방식이나 믿음을 가지고 있기 때문일 수 있습니다.

심리학자 캐롤 Dweck에 따르면, 어떤 사람들은 고정 된 사고 방식을 가지고 있으며, 어떤 사람들은 성장 사고 방식을 가지고 있습니다. 고정된 사고 방식을 가진 사람들은 지능이나 능력이 고정되어 있으며 변화할 수 없다고 믿습니다. 이 사람들은 스케이트하는 법을 배우는 것과 같은 도전에 직면할 때, 새로운 기술이 쉽게 오지 않는다면, 그들은 단순히 그것에 능숙하지 않다고 믿는 경향이 있습니다. 그들은 자신의 기술을 변화시킬 수 있다고 생각하지 않으므로 계속 노력하는 것은 쓸모가 없다고 결정합니다. 성장 마인드를 가진 사람들은 반대의 태도를 가지고 있습니다. 그들은 능력이 열심히 노력하여 발전할 수 있다고 믿고 있으며, 처음에는 성공하지 못하더라도 계속해서 개선하려고 노력합니다.

이러한 다양한 사고 방식은 어떻게 발전합니까? 아이들의 끈기와 성공 동기에 영향을 미치는 한 가지 요인은 그들의 성공이 다른 사람들에 의해 설명되는 방식입니다. 특히, 아이들이 부모와 교사와 같은 성인에게서 받는 칭찬의 종류는 도전적인 과제를 수행하려는 동기에 강력한 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

이 비디오는 뮬러와 드윅이 개발한 방법을 기반으로 어린이 동기부여에 대한 칭찬의 영향을 측정하는 방법을 보여줍니다. 1

Procedure

Results

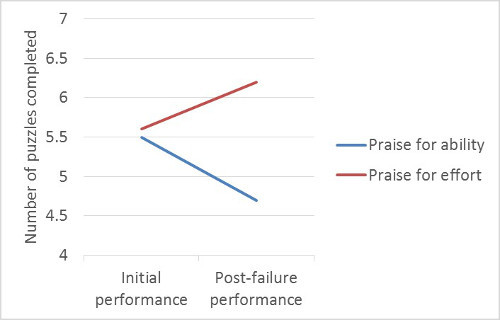

Researchers tested 80 9- to 11-year-old children (n = 40 in each condition) and found that the type of praise children received had a significant effect on their performance. Both groups of children started out with similar performance on the initial puzzles, but the children who were praised for ability showed a significant decrease in their performance after failing at the more difficult puzzles. Children who were praised for effort showed an improvement in performance after the failure experience, suggesting that hearing their initial success was a function of their effort motivated them to work even harder on the puzzles after failing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average initial and post-failure performance for children in each condition.

Applications and Summary

The finding that a brief statement of praise from an experimenter has significant consequences for a child’s motivation to complete a challenging task has major implications for how parents and teachers talk to children. Although saying “You’re so smart” might sound like a good way to praise a child, these findings suggest that doing so fosters the development of a fixed mindset, which can be detrimental to children’s willingness to persist in challenging tasks. In order to foster the development of a growth mindset and motivate children to persist in the face of challenges, parents and teachers should praise children for their effort instead. This is also true in the case of criticism. Criticizing effort (e.g., “You lost the race because you did not practice as much as the winner”) is more likely to motivate children to continue working to achieve a goal than criticizing ability (e.g., “You lost the race because you are not as fast a runner”).

Praise influences mindset, and mindset influences many different variables related to motivation and how people face challenges. Luckily, a mindset is not fixed forever. Even children who typically have a fixed mindset can be shifted into a growth mindset with the right kind of praise and instruction. More importantly, the effects of fostering either a growth or fixed mindset are not limited to children. Carol Dweck has found that these principles also apply to adults in a variety of domains, including the workplace, romantic relationships, and politics.

References

- Mueller, C.M., & Dweck, C.S. Praise for intelligence can undermine children's motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 75 (1), 33-52 (1998).

Transcript

A child’s motivation to succeed at a task—whether a school assignment, sports event, or craft—is heavily influenced by their mindset and how they perceive themselves.

According to psychologist Carol Dweck, children fall into one of two mindset categories: fixed or growth.

Those with a fixed mindset aren’t likely to persist in learning a new skill, like ice-skating, if it doesn’t come naturally to them. They’re not motivated to keep trying, because they believe their abilities can’t change—even with hard work.

In contrast, children with a growth mindset think that their skills can be improved with effort. Thus, even after failing a few times, they are motivated to persist when presented with difficult tasks.

Although a child’s mindset deals with how they think about themselves, it can be shaped by how other people—especially parents and teachers—talk about their traits and abilities.

If a child’s success at a task is praised as being due to inherent ability, this can actually instigate a fixed mindset.

As a result, children may conclude that tasks they find difficult are either beyond their abilities or impossible to complete, resulting in a lack of motivation to persist in performing them.

Using puzzles, this video demonstrates how to explore whether different types of praise affect motivation in children, and describes how to design an experiment, and collect and interpret data, as well as apply the findings to build motivation in both children and adults.

In this experiment, children between the ages of 9 and 11 are asked to complete three sets of ten tangram puzzles.

As these types of puzzles consist of simple shapes, have straightforward instructions, and can be of varying difficulties, they are wonderful tools to assess children’s motivation and persistence at a task.

Children are first given a puzzle set of medium difficulty. The number of puzzles a child successfully completes in five minutes serves as an initial measure of their performance.

Afterwards, children are congratulated on their results, and randomly assigned to one of two praise condition groups: ability or effort.

Children in the first group are told they are smart at puzzles. This type of praise emphasizes children’s puzzle-solving ability, and encourages a fixed mindset.

In contrast, children in the second group are praised for being hard-working, which emphasizes the effort they put into solving puzzles, and fosters a growth mindset.

The type of praise that children receive—and the mindset they develop in response—is expected to influence their performance and motivation to succeed on later puzzles.

Children are then given the second collection of tangram puzzles. The trick here is that these puzzles are much more difficult than the previous ones.

As children are expected to be able to solve fewer puzzles in this round, it is meant to provide them with a “failure” experience. Importantly, this cleverly sets up the third and final collection of tangram puzzles as a challenge to be overcome.

This third set—like the first—is also of medium difficulty. The number of puzzles solved here provides a post-failure measure of performance.

In this instance, the dependent variables are the number of puzzles completed during the initial and post-failure performance measures, respectively, in the first and third tangram sets.

Based on previous work by Dweck, it is expected that a child praised for their effort will complete more puzzles in the third tangram set compared to the first set. In other words, their puzzle-solving performance will be higher after their failure experience.

This is likely due to children perceiving themselves as hard-working in response to this type of praise, which inspires them to want to succeed at solving puzzles.

To begin, select a total of 30 tangram puzzles, 20 of which should be moderately difficult for 9-11 year-olds, and 10 that are very hard for a child this age to complete.

When the child arrives, welcome them and explain that they will be solving three sets of puzzles.

Sit across from the child at a table, and demonstrate how to complete an easy tangram puzzle. Explain that once they start working on a puzzle, it must be successfully solved before they can move onto the next one in a set.

Once the child understands the task, hand them the first set of tangrams and begin a timer. Once 5 min have passed, record the number of puzzles the child solved.

Praise the child according to which group they have been assigned: ability (“You must be smart at these puzzles”) or effort (“You must have worked hard at these puzzles.”)

Afterwards, provide the child with the second puzzle set. Once 5 min have passed, inform them that they did much worse on these problems than the previous ones.

Give each child the third and final tangram set, and again record the number of puzzles they solve after 5 min.

After all three sets have been completed, debrief the child and explain that this study was conducted to evaluate how they reacted to different kinds of praise. Reassure them that they did a great job on all of the puzzles, and explain that the second set was actually meant for much older children.

To visualize the data, graph the mean number of puzzles children solved by praise conditions, pre- and post- the failure experience.

Notice that children who were praised for their effort demonstrated increased post-failure performance, suggesting that this type of encouragement motivated them to persist in their hard work, even when it was challenging.

Now that you know how to design a puzzle-based experiment to study the effects of praise on motivation in children, let’s look at other ways praise—and even criticism—can be used to shape human behavior.

The finding that praising effort, and not individual ability, increased persistence can be easily applied to classroom settings, encouraging children to persevere in fields that are perceived as difficult, like the sciences.

In addition to finding that praising a child’s effort motivated them to succeed, psychologists have found that criticizing effort, rather than ability, also increases motivation, which could influence coaching techniques.

For example, a coach criticizing the amount of time a child practiced, rather than their natural skating ability, may be more effective in motivating that child to succeed in the next competition.

Finally, although we’ve focused here on children, adults are also influenced by mindset, as they are malleable at any age, and over time can switch from being fixed to growth—and vice versa.

As a result, psychologists are exploring how praising effort can be applied in the workplace to foster a growth mindset in employees, and improve job satisfaction and productivity.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video exploring the effects of praise on motivation in children. By now, you should understand how tangram puzzles can be used to investigate this question, and be able to collect and interpret children’s puzzle-solving data. Importantly, we’ve reviewed how different types of praise, targeted at either effort or ability, can affect performance in both children and adults.

Thanks for watching!