Transduction via bactériophage : méthode de transfert de la résistance à l'ampicilline du donneur au receveur E. coli

English

Share

Overview

Source: Alexander S. Gold1, Tonya M. Colpitts1

1 Département de microbiologie, Boston University School of Medicine, National Emerging Infections Diseases Laboratories, Boston, MA

La transduction est une forme d’échange génétique entre les bactéries qui utilise des bactériophages, ou phages, une classe de virus qui infecte exclusivement les organismes procaryotes. Cette forme de transfert d’ADN, d’une bactérie à l’autre par le phage, a été découverte en 1951 par Norton Zinder et Joshua Ledererg, qui ont appelé le processus de « transduction » (1). Les bactériophages ont été découverts pour la première fois en 1915 par le bactériologiste britannique Frederick Twort, puis découverts de façon indépendante en 1917 par le microbiologiste canadien Français Felix d’Herelle (2). Depuis lors, la structure et la fonction de ces phages ont été largement caractérisées (3), divisant ces phages en deux classes. Les premiers de ces cours sont les phages lytiques qui, lors de l’infection, se multiplient dans la bactérie hôte, perturbant le métabolisme bactérien, lysant la cellule et libérant des phages de descendance (4). En raison de cette activité antibactérienne et de la prédominance croissante des bactéries résistantes aux antibiotiques, ces phages lytiques se sont récemment avérés utiles comme traitement de remplacement pour des antibiotiques. La deuxième de ces classes sont les phages lysogéniques qui peuvent soit se multiplier dans l’hôte par le cycle lytique ou entrer dans un état de quiescent dans lequel leur génome est intégré dans celui de l’hôte (figure 1), un processus connu sous le nom de lysogénie, avec la capacité de phage production à être induite dans plusieurs générations ultérieures (4).

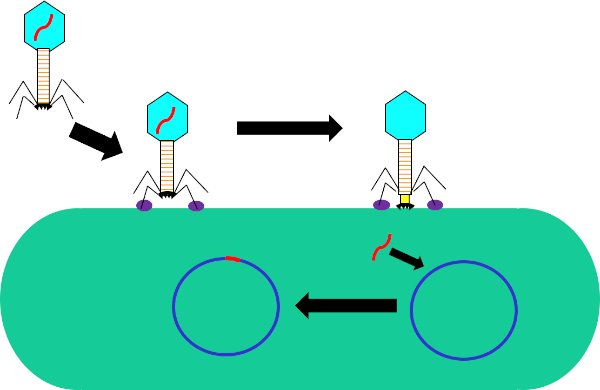

Figure 1 : Infection de la cellule hôte par bactériophage. Adsorption par le phage à la paroi cellulaire bactérienne par des interactions entre les fibres de la queue et le récepteur (violet). Une fois sur la surface de la cellule, le phage est irréversiblement attaché à la cellule bactérienne à l’aide de la plaque de base (noir) qui est déplacé vers la paroi cellulaire par la gaine contractile (jaune). Le génome phage (rouge) entre alors dans la cellule et s’intègre dans le génome de la cellule hôte.

Bien que la transduction bactérienne soit un processus naturel, l’utilisation de la technologie moderne a été manipulée pour le transfert de gènes en bactéries en laboratoire. En insérant des gènes d’intérêt dans le génome d’un phage lysogène, comme le phage, on est capable de transférer ces gènes dans les génomes des bactéries et, par conséquent, de les exprimer à l’intérieur de ces cellules. Alors que d’autres méthodes de transfert de gènes, telles que la transformation, utilisent un plasmide pour le transfert et l’expression des gènes, l’insertion du génome phage dans celui de la bactérie recevable a non seulement le potentiel de conférer de nouveaux traits à cette bactérie, mais permet également mutations naturelles et d’autres facteurs de l’environnement cellulaire pour modifier la fonction du gène transféré.

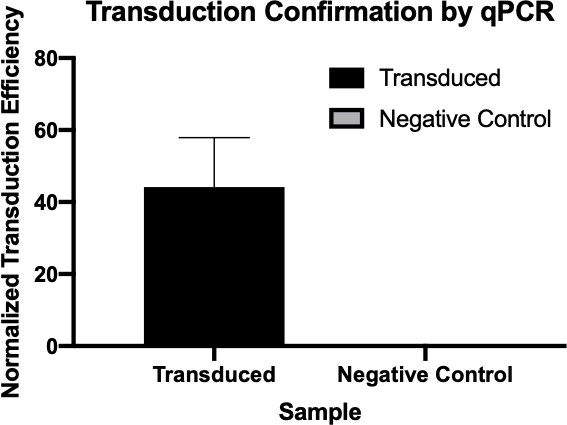

Par rapport à d’autres méthodes de transfert horizontal de gènes, comme la conjugaison, la transduction est assez souple dans les critères requis pour les cellules du donneur et du receveur. Tout élément génétique qui peut s’insérer dans le génome du phage utilisé peut être transféré de n’importe quelle souche de bactéries donneuses à n’importe quelle souche de bactéries receveurs tant que les deux sont permissifs au phage, nécessitant l’expression des récepteurs phages nécessaires sur le surfaces cellulaires. Une fois que ce gène est déplacé hors du génome du donneur et emballé dans le phage, il peut être transféré au receveur. Après la transduction, il est nécessaire de sélectionner pour les bactéries récepteurs qui contiennent le gène d’intérêt doivent être sélectionnés pour. Cela pourrait être fait par l’utilisation d’un marqueur génétique, comme un FLAG-tag ou polyhistidine-tag, pour marquer le gène d’intérêt, ou la fonction intrinsèque du gène, dans le cas des gènes qui codent pour la résistance aux antibiotiques. En outre, PCR pourrait être utilisé pour confirmer davantage la transduction réussie. En utilisant des amorces pour une région dans le gène d’intérêt et en comparant le signal à un contrôle positif, les bactéries qui ont le gène d’intérêt, et un contrôle négatif, les bactéries qui ont subi les mêmes étapes que la réaction de transduction sans phage. Bien que la transduction bactérienne soit un outil utile en biologie moléculaire, elle a joué et continue de jouer un rôle important dans l’évolution des bactéries, en particulier en ce qui concerne l’augmentation récente de la résistance aux antibiotiques.

Dans cette expérience, la transduction bactérienne a été utilisée pour transférer l’encodage génétique pour la résistance à l’ampicilline antibiotique de la souche W3110 d’E. coli à la souche J53 via le bactériophage P1 (5). Cette expérience se composait de deux étapes principales. Tout d’abord, la préparation du phage P1 contenant le gène de résistance à l’ampicilline de la souche du donneur. Deuxièmement, le transfert de ce gène à la souche receveuse par transduction avec le phage P1 (figure 1). Une fois effectué, le transfert réussi du gène de résistance à l’ampicilline pourrait être déterminé par qPCR (figure 2). Si la transduction était réussie, la souche J53 de E. coli serait résistante à l’ampicilline, et le gène conférant cette résistance détectable par qPCR. En cas d’échec, il n’y aurait aucune détection du gène de résistance à l’ampicilline et l’ampicilline fonctionnerait toujours comme un antibiotique efficace contre la souche J53.

Figure 2 : Confirmation d’une transduction réussie par qPCR. En comparant les valeurs Cq détectées pour le gène d’intérêt de la réaction de transduction et de la réaction de contrôle négative, et en normalisant ces valeurs par rapport à un gène d’entretien ménager, on a pu confirmer que la transduction bactérienne a été réussie.

Procedure

Applications and Summary

The transfer of genes to and from bacteria by bacteriophage, while a natural process, has proved extremely useful for a multitude of research purposes. While other methods of gene transfer such as transformation and conjugation are possible, transduction uniquely uses bacteriophages; not only allowing for gene integration into the host genome, but also for gene delivery to multiple bacteria that are not susceptible to other methods. This process, while especially useful in the laboratory, has also been used in the recently emerging field of gene therapy, more specifically in alternative gene therapy, a therapeutic strategy that utilizes bacteria to deliver therapeutics to target tissues, many of which are not susceptible to other delivery methods and have much clinical relevance (8,9).

References

- Lederberg J, Lederberg E.M., Zinder, N.D., et al. Recombination analysis of bacterial heredity. Cold Spring Harbor symposia Quantitative Biol. 1951;16:413-43.

- Duckworth DH. "Who Discovered Bacteriophage?". Bacteriology Reviews. 1976;40:793-802.

- Yap ML, Rossman, M.G. Structure and Function of Bacteriophage T4. Future Microbiol. 2014;9:1319-27.

- Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze, Z., Morris, J. G. Bacteriophage Therapy Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2001;45(3):649-59.

- Moore S. Sauer:P1vir phage transduction 2010 [Available from: https://openwetware.org/wiki/Sauer:P1vir_phage_transduction].

- Kobayashi A, et al. Growth Phase-Dependent Expression of Drug Exporters in

- Escherichia coli and Its Contribution to Drug Tolerance. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188(16):5693-703.

- Rocha D, Santos, CS, Pacheco LG. Bacterial reference genes for gene expression studies by RT-qPCR: survey and analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2015;108:685-93.

- Pálffy R. et al. Bacteria in gene therapy: bactofection versus alternative gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2006 13:101-5.

- O'Neill JM, et al. Intestinal delivery of non-viral gene therapeutics: physiological barriers and preclinical models. Drug Discovery Today. 2011;16:203-2018.

Transcript

Bacteria can adapt quickly to a fast-changing environment by exchanging genetic material and one way they can do this is via transduction, the exchange of genetic material mediated by bacterial viruses. A bacteriophage, often abbreviated to phage, is a type of virus that infects bacteria by first attaching to the surface of the host and then injecting its DNA into the bacterial cell. It then degrades the host cell’s own DNA and replicates its viral genome, whilst hijacking the cell’s machinery to synthesize many copies of its proteins. These phage proteins then self-assemble and package the phage genomes to form multiple progeny. However, due to the low fidelity of the DNA packaging mechanism, occasionally, the phage packages fragments of bacterial DNA into the phage capsid. After inducing the lysis of the host, the phage progeny are released and, once such a phage infects another host cell, it transfers the DNA fragment of its previous host. This can then recombine and become permanently incorporated into the new host’s chromosome, thereby mediating gene transfer between the two bacteria.

To carry out phage transduction in the laboratory requires a donor strain that contains a gene of interest, a recipient strain that lacks it, a phage that can infect both the strains, and a method to select the transduced bacteria. In most cases, this will be a selective solid growth media that supports the growth of transduced bacteria but inhibits the growth of non-transduced ones. To begin, the donor strain that contains the gene of interest is cultured in a liquid growth medium. When all the bacteria are actively dividing in the log phase of their growth, the culture is inoculated with the target phage. After three to four hours of incubation, when nearly all the bacteria have lysed and released the phage particles, the donor phage lysate is inoculated into a freshly grown culture of the recipient bacterial strain. After a brief incubation of one hour, the culture should now contain a mixture of transduced and non-transduced bacterial cells and this is screened for the transduced cells by spreading a fraction of the suspension onto an appropriate selective solid growth media. Upon further incubation, the transduced cells should grow and multiply to yield visible colonies. These colonies can then be selected for further analysis using a variety of methods to further confirm successful transduction, such as colony PCR, DNA sequencing, or quantitative PCR.

Before starting the procedure, put on any appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves. Next, sterilize the workspace with 70% ethanol and wipe down the surface.

After this, prepare three one-milliliter aliquots of LB salt solution. Now, prepare a donor strain culture by adding 100 microliters of E. coli to a 15 milliliter conical vial containing five milliliters of LB growth medium with 500 micrograms of ampicillin. Then, grow the culture overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration and shaking at 220 rpm. The next day, wipe down the bench top with 70% ethanol before removing the culture from the shaking incubator. Next, dilute the overnight culture one to 100 by adding 10 microliters of donor strain to 990 microliters of fresh LB supplemented with salt solution.

Allow the bacterial dilution to grow at 37 degrees Celsius for two hours with aeration and shaking at 220 rpm. Once the cells have reached early log phase, remove the culture from the incubator, add 40 microliters of P1 phage to the culture and incubate again. Continue to monitor the cells for one to three hours until the culture has lysed. Next, add 50 to 100 microliters of chloroform to the lysate and mix by vortexing. Then, centrifuge the lysate to remove debris and transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube. Add a few drops of chloroform to the supernatant and store it at four degrees Celsius for no more than one day.

To begin the transduction procedure, obtain a one milliliter culture of recipient strain. Next, transfer 100 microliters of donor phage lysate into a 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tube and incubate it at 37 degrees Celsius with the cap open for 30 minutes to allow any remaining chloroform to evaporate. While the donor phage lysate incubates, pellet the recipient strain cells via gentle centrifugation. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 300 microliters of fresh LB containing 100 millimolar magnesium sulfate and five millimolar calcium chloride.

Next, set up the transduction reaction by combining 100 microliters of the recipient strain and 100 microliters of the donor phage lysate in a microcentrifuge tube. Then, set up the negative control by combining 100 microliters of the recipient strain and 100 microliters of the LB with magnesium sulfate and calcium chloride. After incubation, add 200 microliters of one molar sodium citrate and one milliliter of LB to both tubes, and mix by gently pipetting up and down. Then, after the tubes have been incubated for an hour, gently pellet the cells via centrifugation.

After centrifuging, discard the supernatant and resuspend the pelleted cells in 100 microliters of LB with 100 millimolar sodium citrate. Vortex the solutions and pipette the entire transduced sample onto an LB agar plate with 1X ampicillin. Finally, pipette the entire volume of the negative control cell mixture onto an LB agar plate without ampicillin. After incubating the plates overnight at 37 degrees Celsius, use a sterile pipette tip to pick three to four colonies from the transduction plate and streak them onto a new LB agar plate containing 1X ampicillin and 100 microliters of one molar sodium citrate. Repeat this plating method for the negative control on another LB agar plate containing only 100 microliters of one molar sodium citrate. Then, incubate the plates at 37 degrees Celsius overnight to allow colonies free of phage to grow.

The next day, wipe down the bench top with 70% ethanol before removing your plates from the incubator. Using a sterile pipette tip, pick three colonies from the transduction plate and add them each to a separate tube containing five milliliters of LB media. Then, select three colonies from the negative control plate and add them to another tube containing five milliliters of LB media. Grow the cultures overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration and shaking at 220 rpm. After sterilizing the bench top as previously demonstrated, use a DNA miniprep kit to isolate DNA from 4.5 milliliters of each culture according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, elute the DNA with 35 microliters of nuclease-free water and measure the resulting concentration by lab spectrophotometer. Finally, prepare glycerol stocks by adding the remaining 0.5 milliliters of both bacterial solutions to 0.5 milliliters of 100% glycerol.

To confirm transduction, first prepare two qPCR master mixes for 24 qPCR reactions. For the first master mix, add 150 microliters of qPCR buffer mix to a microcentrifuge tube and 12 microliters each of a forward and reverse primer designed to amplify the ampicillin resistance gene. Next, prepare a second qPCR master mix by adding 150 microliters of qPCR master mix to a microcentrifuge tube and then adding 12 microliters each of a forward primer and reverse primer designed to amplify a housekeeping gene.

For each qPCR reaction, combine 100 micrograms of experimental DNA from each reaction with 14.5 microliters of qPCR master mix. Now, prepare the remaining reactions as previously demonstrated. Transfer the reactions to a thermocycler preheated to 94 degrees Celsius and then initiate the program. Finally, use the cycle quantification, or Cq, values generated by qPCR to calculate the normalized transduction efficiency of the ampicillin resistance gene.

The cycle quantitation, or Cq, values for the genes of interest were tabulated for each of the negative controls and transduced samples. Low Cq values, typically below 29 cycles, like the transduced samples in this example indicate high amounts of the target sequence.

A housekeeping gene, also tabulated here, is used as a loading control to normalize the amount of DNA in each reaction and as a positive control to ensure the qPCR is working. Provided the same amounts of the housekeeping gene are loaded, it is found at relatively the same rate in each sample.

Next, to calculate the delta Cq value for each sample, subtract the Cq value of the housekeeping gene for each sample from the Cq value of its corresponding target gene. For example, the delta Cq of the first negative control is 13.54. Then, use this value to calculate the normalized transduction efficiency of each sample using the formula shown here. Finally, the average normalized transduction efficiency for each sample group can be calculated.